‘To Cost You in Blood’ – Rory O’Connor’s 1916 Rising and Aftermath

The first in a series of articles looking at Rory O’Connor’s role in the Irish revolutionary period. By Gerard Shannon.

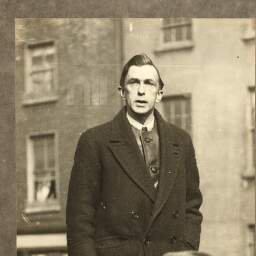

In most accounts of the events leading to the foundation of the Irish Free State, Rory O’Connor remains best known for his controversial leadership of the anti-Treaty IRA faction in 1922, at the outset of what became known as the Irish Civil War.

O’Connor’s tenure as IRA leader is often defined by a flippant – and likely inaccurate – remark at a press conference in which he seemed to suggest the IRA may seriously consider a military dictatorship in opposition to the then-new Free State government. [1]

Rory O’Connor is best known for his role in the Civil War. His prior career has been overlooked.

There has also been much analysis of the circumstances surrounding O’Connor’s execution at the age of 39 by the Irish Government in December 1922. This is chiefly due to one of the signatories for the order for O’Connor’s death being government minister Kevin O’Higgins, with O’Connor only having served as best man at O’Higgins’ wedding barely a year before; their story a symbol of the bitter nature of the 11-month civil war. [2]

Despite some scattered instances of personal correspondence in this crucial period of his life, O’Connor left behind no detailed personal reminisces detailing his ideology, or his involvement and feelings in the last few years of his life; perhaps going some way to explaining why (to date) he is yet to be the subject of a major study, or biographical work. This is despite the pivotal role he played in the republican opposition to the Anglo-Irish Treaty and to the Provisional Government it established.

Dorothy McArdle, in her seminal work The Irish Republic which is sympathetic to the anti-Treaty position, writes of O’Connor: “a man of uncompromising spirit and a believer in political methods when these were backed by physical force.”[3]

IRA Volunteer Joseph Lawless, however, referring to his interaction with O’Connor in the Curragh military camp during the War of Independence, implied that as a leader O’Connor was irresponsible and not mentally balanced – ultimately dismissing him as “a crank.” Lawless makes it clear that when he sided with Michael Collins over the Treaty dispute, his personal impressions of Rory O’Connor and Eamon de Valera were key to his decision. [4]

What remains little explored are the circumstances in which Rory O’Connor ascended to a leadership position in the IRA during both the War of Independence and the Civil War.

To fully understand this, one must first look at O’Connor’s associations with both the IRB and the Irish Volunteers leading up to, and including, the dramatic events of the 1916 Easter Rising and its aftermath.

Early Years and Activism

O’Connor was born on the 28th November 1883 at a residence on Kildare Street, his full name being Roderick (Rory) Ignatius Patrick O’Connor. He was the third son of John O’Connor, a solicitor.[5]

In one of the last letters written before his execution, O’Connor briefly mentions to his father they often greatly disagreed in the past, likely due to his political activities and increasingly radical stances in the last few years of life. [6]

O’Connor’s radical activism was closely linked with his fateful friendship with future rebel leader Joseph Plunkett. The two men first met when O’Connor joined the Young Ireland branch of the United Irish League in 1908. [7] The United Irish League (UIL) was originally a breakaway organisation from a then-divided Irish Parliamentary Party, and focused its campaign efforts on agrarian reform and Irish self-government.

O’Connor’s radical activism was closely linked with his fateful friendship with future rebel leader Joseph Plunkett.

The Young Ireland branch, of which both Plunkett and O’Connor were members, was founded by Thomas Kettle, and was considered a progressive branch of the UIL for young intellectuals, such as the pacifist and feminist activist Francis Sheehy Skeffington.[8] Both Plunkett and O’Connor were compelled to eventually leave the UIL due to the growing influence of the Irish Parliamentary Party on the organisation in this period, and its eventual absorption into the larger party itself. [9]

At the same time, O’Connor made some progress in his career as an engineer. His early education included stints at Mary’s College, Rathmines and Clongowes Wood College, before going on to qualify as a railroad engineer, taking BE and BA degrees in the Royal University of Ireland (dissolved in 1909 to make way for the National University of Ireland).

After holding a job as an engineer on the Midland Great Western Railway, O’Connor opted to emigrate to Canada to build on his career prospects. Arriving in 1910, O’Connor would go on to hold jobs in constructing railroad with both the Canadian Pacific Railway and Canadian Northern Railway companies. His brother Norbert estimated Rory was involved with the construction of 1500 miles of railroad.[10]

After four years, O’Connor opted to return to Ireland by early 1915, and it would appear he contemplated joining the British Army to fight in the Great War on the European continent. However, not long after his return, he soon fell into the social spheres of his old Young Ireland branch friends, Thomas Dillon and Joseph Plunkett.[11]

Plunkett, of course, was by this time on the Military Council of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB). Since the outbreak of the war, the Military Council of the IRB – particularly due to the influence of the Fenian, Thomas Clarke and his closest ally, Sean MacDiarmuida – was keen to take advantage of Britain’s involvement in the war on the European continent and ferment a revolution against British rule in Ireland.

Perhaps influenced by Plunkett, O’Connor’s on his return joined Eoin MacNeill’s radical anti-war Irish Volunteers and he was also sworn into the IRB, which maintained an influence on the leadership of MacNeill’s nationalist militia.

The Plunketts and Larkfield

On his return to Ireland, Rory O’Connor would closely integrate himself with the Plunkett family and their associates, becoming a regular visitor to the Plunkett family estate at Larkfield based in Kimmage, then a country area in south-west Dublin.

In her memoir of the period, Plunkett’s sister (and carer), Geraldine recalled her impression of O’Connor: “He was a smallish, very dark man, dark skin, blue jaws, he had to shave twice a day and had such a deep voice that it seemed to slow his speech, yet he had great charm.”[12]

In January 1916, Joseph Plunkett assigned O’Connor as head of engineering on his Volunteer staff, which also included Plunkett’s younger brothers John (or Jack), George, as well as his friends Michael Collins, Con Keating, Fergus Kelly, and a future brother-in-law, Thomas Dillion. Naturally, all were members of the IRB.[13] This was also the beginning of a strong friendship between Collins and O’Connor, which became stronger when they worked together during the subsequent War of Independence.[14]

Geraldine Plunkett-Dillion recalled that O’Connor had a “very frustrating love-affair” with Joseph’s younger sister, Fiona.

As a result of his proximity to such a key figure as Joseph Plunkett, O’Connor was privy to certain meetings at Larkfield with key IRB figures involved in the planning of the 1916 rebellion. Though O’Connor betrayed no reluctance to fight, he seemed wary of the bloodshed such a rebellion would involve, one remark attributed to him at one such meeting being: “Do you realise what this effort is going to cost you in blood? But if you now decide in fighting I am with you.”[15]

The closeness of O’Connor’s relationship with the wider Plunkett family in this period is reflected in a remark of John ‘Jack’ Plunkett’s remarking that despite it then being three decades since O’Connor’s execution in the civil war that: “I would like to say a good deal about Rory but it [still] hurts too much.” [16]

Nor was it all platonic. Geraldine Plunkett-Dillion recalled that O’Connor had a “very frustrating love-affair” with Joseph’s younger sister, Fiona, that had ended by the time of the Civil War; Fiona herself suffered a degree of mental illness throughout what was a turbulent life, though Plunkett-Dillion does not specifically cite this as the cause of the relationship troubles.[17]

Laurence Nugent remembered that Rory and Fiona’s romance was little known to O’Connor’s contemporaries, and that O’Connor’s death left her devastated. Though out of respect, Nugent deliberately leaves Fiona unnamed in his recollections.[18]

In addition to his Volunteer activities, O’Connor took up an engineering position in Dublin Corporation in late 1915.[19] Along with Thomas Dillon (who would become husband of Plunkett’s sister, Geraldine), O’Connor also attempted a side-career and set-up the Larkfield Chemical Company at the Plunkett estate.

The intention of the two men was to produce asprin though the business venture is dismissed by Geraldine Plunkett-Dillion as “a very small affair.”[20] Patrick J. Little puts it succinctly: “… instead of a factory for making asprin, they started a factory for making explosives.”[21]

The Kimmage Garrison

Despite Geraldine’s recollection, the Company was apparently busy enough to provide a paid day’s work every now and then for some of the 40 members of the Volunteers who lived in specifically built quarters in a barn on the Larkfield estate, on whose grounds they would drill and train.

These men, from various backgrounds, as a body became known as the’ Kimmage Garrison’.[22] A recent study asserts the garrison grew to about 90 men by April 1916, including Volunteers hailing from Glasgow, Liverpool and London.[23]

Rory O’Connor manufactured explosives in Kimmage for the Volunteers.

At the end of March 1916, O’Connor and others on Plunkett’s staff barricaded the house to ward off what was assumed to be a pending attempt by members of the police and military to besiege the estate. The belief amongst those of the Kimmage Garrison that that the increasing practice maneuvers and build-up of arms on the estate came to the authorities’ attention. Plunkett suspected this was part of an expected move against the Volunteers, though after a few hours, both police and military withdrew and did not move in on the property.[24]

This was only one of several dramatic developments as the weeks counted down to the IRB Military Council’s proposed nationwide rebellion on Easter Sunday 1916 utilising the Irish Volunteers and James Connolly’s Irish Citizen Army. In the week just prior to the rebellion, Rory O’Connor would be central to one particularly contested aspect of the planning of the Rising.

Castle Document

Patrick J. Little, an old associate of O’Connor and Plunkett’s in the Young Ireland branch of the United Irish League, became editor of the New Ireland newspaper in February 1916. New Ireland was a publication which tended to be wholly supportive of the Irish Parliamentary Party and the Home Rule movement, at one point Rory O’Connor being a member of the office staff on Fleet Street.[25]

On becoming editor, Little made sure to tell “Rory O’Connor that, if at any time he wanted to use it specifically for national purposes, I was willing to take the risk.” Some weeks later, Little was approached by O’Connor who informed him of measures being taken by the British administration at Dublin Castle to suppress the Irish Volunteers.

O’Connor, after some time produced for Little what became known as the ‘Castle Document’ – a brief that suggested that a British move to disarms and arrest the radical nationalist movement was imminent. It was be the casus belli for the Rising. Some maintain it was a real leak, others that it was fabricate to make Eoin MacNeill and other Volunteer leaders go along wit the Military Council’s plan for insurrection.

O’Connor was involved in disseminating the Castle Document, allegations that the British were about to suppress the Volunteer movement.

Little notes O’Connor set up the type himself, probably at a printing press that Plunkett owned in Larkfield. In an amusing account, Little recalls O’Connor telling him: “When he had half-finished [the Castle Document], he knocked it with his elbow, and had to do it over again.” When the document in question was given to Little to publish, it had no capitals or punctuation.

However, after only seven copies of this edition of New Ireland were published with the Castle Document, to Little’s dismay, the Dublin Castle authorities were alerted and ensured the offending article was removed from the publication.[26]

There are at least two recorded instances where O’Connor, conveying a message on Joseph Plunkett’s orders, approached key allies amongst the Volunteers – and outside the IRB conspiracy – to convince them of the Castle Document’s validity. Dr. Seamus O’Kelly recalls O’Connor setting up a meeting of politically like-minded friends in a restaurant on College Street near Trinity College shortly before the Rising, the group including Kelly himself, Patrick J. Little and Francis Sheehy Skeffington.

O’Kelly recalls that O’Connor “informed us of Joe Plunkett’s opinion that it would be worthwhile to publish the whole proposal [to suppress the Volunteers] in the newspapers to stir up the people, but that it should be first communicated to the Bishops.” O’Kelly himself was assigned to pass the Document to the Archbishop of Dublin, William Walsh, only getting as far as his Secretary.[27]

Patrick J. Little also briefly refers to an instance of meeting Eoin MacNeill at his home with the same group, including O’Connor, on either the Monday or Tuesday of Holy Week to persuade MacNeill as the Volunteers’ Chief-of-Staff of the document’s validity and to push for its publication in the national newspapers. [28]

The Rising

At the Rising’s outbreak, O’Connor adopted the name ‘Cyril Cooper’. The reason was his father at the time had a position as Commissioner of the Congested Districts Board, and O’Connor wished to protect his father’s position if he was arrested and the necessity arose. Given his proximity to Joseph Plunkett, it is not surprising he was attached to what became the main rebel garrison at the GPO, serving as an Intelligence Officer.[29]

O’Connor avoided arrest during the 1916 Rising by using a false identity.

Given that most of O’Connor’s movements through Easter Week resulted in him moving between at least two rebel positions, and also to Larkfield in the south of the city, he devised a clever method to pass through British army lines with rebel dispatches from the GPO.

In his possession he had a letter to his father, then a solicitor in the Land Commission, with the signature of the Chief Secretary of Ireland, Augustine Birrell. It is inferred that he tried this method to get through British Army checkpoints more than once.[30] Laurence Nugent, then a member of the National Volunteers, who encountered O’Connor at least twice during Easter Week, mentions the bizarre image of O’Connor often carrying “a half a ham and some mutton, playing the part an ordinary shopper passing through army lines.[31]

Geraldine Plunkett-Dillon who married Thomas Dillon in the sacristy of Rathmines Church on Easter Sunday, (with Rory O’Connor as best man) – later recalled to her amusement Dublin Castle detectives trying to barge into the sacristy and O’Connor along with her brothers George and Jack “putting them out.”[32] Newly married Geraldine stayed with her new husband at their rented room in the Imperial Hotel on O’Connell Street; both very unsure of the future amid the impending insurrection.

Several times during both Easter Sunday and the Rising’s outbreak the following day, Plunkett-Dillon recalls being conveyed several messages by a visiting Rory O’Connor. The first instance being in the afternoon of Easter Sunday whereby O’Connor informed both her and her husband of the consequences of MacNeill’s countermanding order and “that as far as he knew the Rising was off for that day but to look out from twelve o’clock the next day.”

Naturally, both Geraldine and her husband’s had a bird’s eye view of O’Connell Street when the General Post Office was taken the next day by republican forces; O’Connor returning to their hotel room several times to keep them updated. At around six o’clock in the evening on another visit, O’Connor was requested by Geraldine to ask could she assist her brother Joseph in the Post Office. (Geraldine normally taking the role of Joseph’s carer in the family, given his various illnesses).

O’Connor informed the couple that there was no need for any more insurgents in the GPO, particularly emphasising to Geraldine there were enough women for nursing and cooking. Instead, Joseph Plunkett had suggested all three attempt to return to Larkfield to try to make more explosives – O’Connor first staying overnight at his father’s home in Monkstown, with the couple staying at their home on Belgrave Road.

Meeting at Larkfield the next day, Rory O’Connor and Thomas Dillon agreed there was little in the way of resources to help them in their assigned task. Deciding to return to the city, both men appear to have weighed up returning to the GPO, with O’Connor deciding he will instead take up the task of carrying various messages from the main rebel garrison. Demonstrating his closeness to the couple, O’Connor would frequently return to the Dillons’ home during Easter Week to provide them with updates to the situation.[33]

During Wednesday, Laurence Nugent, met Rory O’Connor entering his butcher shop on Lower Baggot Street with a message from the GPO. Nugent had sided with the Redmondite majority during the split in the Volunteers over support for Britain’s war effort in 1914. However, the National Volunteers as an organisation had begun to fade by this time, and Nugent remained relatively friendly with some former associates in the minority grouping under MacNeill.

O’Connor implored Nugent in his capacity as an officer of the National Volunteers to get in touch with members of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers, and “offer them £2 per man if they were to join up with the Irish Volunteers. These were Pearse’s instructions.”

Nugent only vaguely recalls these instructions, not surprising as he emphasises he did not take them seriously, particularly as the Royal Hospital of Kilmainham – where he assumed the Fusiliers were based – was a British army garrison.[34]

It was on subsequent visit to Nugent’s shop that O’Connor arrived after being under heavy gunfire. On entering Nugent’s shop with Captain T. J. Cullen, also of the National Volunteers, Cullen remarked to O’Connor: “That was a close shave.”

Nugent removed O’Connor’s hat, incredulous he had survived given he noticed the hat was “bored in two places at the front…” Investigating further, Nugent “parted Rory’s thick black hair and discovered an upward red patch as if it had been burned. It then begun to pain him.”[35]

The gunfire that is identified as coming from the direction of rebel snipers from the College of Surgeons, with a bullet ricocheting off a metal box and hitting O’Connor.[36] At least one other source asserts O’Connor may also have been hit in the ankle by a stray bullet.[37]

It is likely both men ensured the injured O’Connor was admitted to Mercer’s hospital. However, the nurses suspected Rory O’Connor was a Volunteer, saying he should be shot because he had in his possession a holy medal Fiona Plunkett had given him. Once a doctor named as Maunsel realised this he had O’Connor moved to a nursing home in Leeson Street. It was here O’Connor recuperated under the Cyril Cooper name for three weeks until his younger brother Norbet found him.[38]

Incredibly, this ruse worked and O’Connor – unlike so many of his fellow rebels and innocent civilians – evaded capture by British army authorities in the aftermath of the rebels’ defeat and the subsequent surrender.

Aftermath

O’Connor attempted to return some semblance of stable civilian life following his recovery in the aftermath of the Rising, part of which involved his attempt with Thomas Dillon to revive the Larkfield Chemical Company, as well his on-going employment with Dublin Corporation.

However, the two men’s attempt to revive their business venture was complicated that the Larkfield estate was seized from the Plunkett family, who were under an investigation involving the Ministry of Munitions of War in Whitehall, London and the Director of Munitions in Ireland. One engineer who inspected the site determined “Dillon and O’Connor were manufacturing phenol for high explosives… “[39]

Rory O’Connor was instrumental in getting the separatist movement back on its feet after 1916.

Both O’Connor and Dillon pushed for compensation, making an application to the Property Losses Committee in late 1916 to try and get some funds for the loss of the company, alleging British soldiers had looted the Larkfield estate in the aftermath of the Rising. Ultimately, the claim was rejected due to the estate’s association with Joseph Plunkett.[40] Similarly, in March 1917, the Dublin Metropolitan Police rejected a request from O’Connor and Dillon to enter the mill on the estate and destroy the chemicals still in storage in there.[41]

By 1917, O’Connor had become a pivotal figure in the rise of the slowly resurgent Irish Volunteers, having been one of those who helped keep the organisation intact until the amnesty given to those imprisoned after the rebellion by December 1916.

As Laurence Nugent, who had joined O’Connor in these efforts, remarked, to those who had evaded capture: “… the war was still on. Rory mentioned it did not stop at any time… “[42] O’Connor helped to form the Prisoner’s Aid Committee, to give relief to the families of imprisoned rebels, an organisation that later merged with the important and influential National Aid Association.[43]

O’Connor also had a central role in organising the funeral of Muriel MacDonagh, the widow of Rising leader, Thomas MacDonagh, who died of heart failure in July 1917 whilst swimming during a holiday in Skerries funded by the National Aid Association.[44] Given her death was barely a year since Thomas’ execution, it was used as a major propaganda event for the national movement, with 4000 Irish Volunteers marching behind Muriel MacDonagh’s coffin on the way to the burial in Glasnevin.[45]

During this period, 1916-17 Rory O’Connor also come to prominence in the political wing of the republican movement. The previously minuscule separatist party Sinn Féin was wrongly associated with the defeated rebels in the understanding of both the Irish public and British authorities, but the misconception became a reality after the Rising, when the party was taken over as a vehicle for militant republicanism.

O’Connor was among those seeking to use the party as an instrument to take advantage of the changing public attitude throughout the country. Giving his closeness to the family, it is not surprising that O’Connor became closely allied with Joseph Plunkett’s father, Count George Noble Plunkett, following the Count’s win for Sinn Féín in the Roscommon by-election of January 1917.

O’Connor was also central to the organizing and formation of Count Plunkett’s own political movement, the Liberty Clubs – the Count’s own attempt to dominate the new political movement.[46] This culminated in the formation of a committee of advanced nationalists at a meeting in the Mansion House in April 1917, with O’Connor on the faction of the committee opposed to the Sinn Féín faction led by the party’s founder, Arthur Griffith.

In a meeting with Griffith’s faction at the Sinn Féin headquarters in Harcourt Street, O’Connor is recalled as arguing “the case of for the whole of the national movement declaring itself in favor of a republican policy”; as Griffith and his followers tended to prefer a more broad separatist policy in opposition to British rule in Ireland, in the form of dual-monarchy.[47] Despite these efforts, the Count was ultimately defeated in his attempt at this takeover and it paved the way for all factions of advanced nationalists and republicans uniting under the Sinn Féin banner at the party Ard Fheis in October of that year.[48]

Though O’Connor was involved in forming the Mansion House committee, to many in this period he remained a relatively unknown figure – though Laurence Nugent makes clear O’Connor’s growing influence when referring to him as “a great silent worker” and “the strong man behind the scenes” in both the political and military spheres of the national movement. [49]

Indeed, in only two years since his return to Ireland from Canada, by way of his personal associations and professional skills, Rory O’Connor had quickly worked his way through the ranks of the IRB, the Irish Volunteers and finally, Sinn Féin. His burgeoning roles in both the political and military spheres of the republican movement would only increase in influence as the nature of British rule in Ireland would be challenged to greater effect in the next revolutionary phase commonly referred to as the Irish War of Independence.

Gerard Shannon is a historian residing in Skerries, Co. Dublin. He can be found on Twitter at https://twitter.com/gerry_shannon

References

[1] See Kissane, Bill, The Politics of the Irish Civil War, Oxford University Press, United States (2005), page 69 and Andrews, C.S., Dublin Made Me, The Lilliput Press, Dublin (2001 edition), page 233

[2] For instance, see Hopkinson, Michael, Green Against Green: The Irish Civil War, Gill & Macmillian Ltd, Dublin (2004 edition), pages 190 – 92

[3] McArdley, Dorothy, The Irish Republic, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York (1965 edition), page 213

[4] Lawless, Joseph, Bureau of Military History Witness Statement No: 1043, pages 373 – 374, 404

[5] O’Connor, Norbert, BMH W/S No: 527, page 1

[6] O’Connor’s last letter to his father is transcribed on O’Dwyer, Martin, Seventy-Seven of Mine Said Ireland, Deshaoirse, Cork (2006), page 54

[7] O’Brolchain, Honor, Joseph Plunkett (16 Lives), O’Brien Press, Dublin (2012), page 107

[8] McArdle, page 72, O’Brolchain page 217

[9] Plunkett Dillon, Geraldine, All in The Blood: A memoir of the Plunkett family, the 1916 Rising and the War of Independence (edited by Honor O’Brolchain), A. & A. Farmer Ltd, Dublin (2006), page 145

[10] O’Connor, Norbert, BMH W/S No: 527, page 1

[11] Little, Patrick J., BMH W/S No: 1769, page 7

[12] Plunkett Dillon, page 314

[13] lbid, page 203

[14] lbid, page 313

[15] Nugent, Laurence, BMH W/S No: 907, page 42

[16] Plunkett, John, BMH W/S No: 865, Part II, page 15

[17] Plunkett Dillion, page 313

[18] Nugent, Laurence, BMH W/S No: 907, page 43

[19] lbid, page 42

[20] Plunkett Dillion, page 164

[21] Little, Patrick J., BMH W/S No: 1769, page 8

[22] O’Brolchain, page 335

[23] Matthews, Ann, The Kimmage Garrison. 1916: Making billy-can bombs at Larkfield, Four Courts Press, Dublin (2010), pages 7, 25

[24] O’Brolchain, page 360

[25] Connell jnr, Joseph E.A., Dublin in Rebellion: A Dictionary 1913 – 1923, The Lilliput Press, Dublin (2009), page 199

[26] Little, Patrick J., BMH W/S No: 1769, pages 10 – 11

[27] O’Kelly, Seamus, BMH W/S No: 471 , page 1 – 2

[28] Little, Patrick J., BMH W/S No: 1769, page 13

[29] Nugent, Laurence, BMH W/S No: 907, page 43; see also Wren, Jimmy, The GPO Garrison: Easter Week 1916 – A Biographical Dictionary, Geography Publications, Dublin (2015), page 252

[30] Little, Patrick J., BMH W/S No: 1769, pages 13 – 14

[31] Nugent, Laurence, BMH W/S No: 907, No: 30 – 31

[32] Plunkett Dillon, page 221

[33] lbid, page 221 – 227

[34] Nugent, Laurence, BMH W/S No: 907, page 32

[35] lbid, page 30

[36] Little, Patrick J, BMH W/S, page 14

[37] Both Plunkett-Dillon, page 230, and Nugent, Laurence, BMH W/S No: 907, page 43 refer to the gunfire that injured O’Connor coming from the College of Surgeons, the former mentioning the ankle injury.

[38] Plunkett-Dillon, page 230

[39] Matthews, pages 49 – 50

[40] lbid, 49, 51

[41] lbid, page 54

[42] Nugent, Laurence, BMH W/S No: 907, page 50

[43] Little, Patrick J., BMH W/S, page 14

[44] Nenagh News, July 14th 1917, page 4

[45] Newspaper clipping (with photograph) from unknown newspaper published Saturday, 14th July 1917 donated to author by Muriel McAuley, Muriel MacDonagh’s granddaughter.

[46] lbid, page 19

[47] lbid, pages 20 – 21

[48] For an account of the events of the Ard Fheis, see Laffan, Michael, The Resurrection of Ireland: The Sinn Féin Party 1916 – 1923, Cambridge University Press, New York (2005), pages 116 – 121

[49] Nugent, Laurence, BMH W/S No: 907, pages 42, 91 – 92