The Irish Army, the UN, Jadotville and the Congo

By John Dorney. For further context see our interview with Declan Power here.

October 2016 saw the launch of a new Netflix film about the ‘Siege of Jadotville’ in 1961, where 150 or so Irish Army UN troops were besieged and ultimately captured (after putting up a good fight) by Katangese and European mercenary troops.

The film itself is good entertainment,the action is well shot, the performances are solid and it does a reasonable job of explaining some of the complexities involved to an Irish and international audience.

The wider political context might need some greater examination however, before the siege of Jadotville and the Irish Army’s role in the Congo are promoted to unsullied sources of national pride.

The Congo crisis

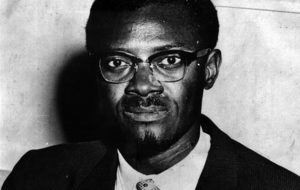

The Congo became independent of Belgium in 1960, led initially by a firebrand nationalist, Patrice Lumumba. Almost immediately, the new Republic of the Congo, a vast state covering much of central Africa, lapsed into disorder. A mutiny of the Army against their Belgian officers led to attacks on European civilians and to the Belgians redeploying troops there.

The chaos descended into civil war as two Congolese provinces, Katanga and South Kassai, backed by Belgium and to a lesser extent by France, declared themselves to be independent states.

Lumumba, who felt spurned by the west, looked for aid to the the Soviet Union, and with their help, dispatched his armed forces to put down the rebellions, leading to widespread disorder and loss of life.

Congo became independent in 1960 and was immediately plunged into civil war.

The UN mission, of which Irish troops became a part, was, at first to protect civilians and to restore order, with the wider aim of preventing a clash of the Cold War antagonists in Africa.

Toaiseach Sean Lemass and Frank Aiken, the latter a one time IRA guerrilla commander but by then a veteran of multiple ministerial jobs and Minister for External Affairs, agreed to provide Irish troops, who served alongside Swedish and Indian and other contingents.The first Irish unit in the Congo, the 32nd Battalion, was sent to Kivu province in the east, where it sustained no casualties.

However, as it developed, the UN force received a mandate to stop the secession of the Katanga province from the Congo. Katanga contained important mines and a Belgian sponsored local leader named Moise Tshombe attempted to secede, basically to control the mineral resources. Katanga also claimed to be a safe haven for Europeans, who were being attacked in other parts of the Congo.

Enter Conor Cruise O’Brien. O’Brien was acting as representative of the UN’s Secretary General, Dag Hammarskjold with regard to Katanga. O’Brien insisted that UN peacekeeping troops should be deployed to block the illegal secession of Katanga from the Congo.

It appears as if both O’Brien and Frank Aiken interpreted the Katanga situation as vindicating the right of newly independent countries to be free of outside interference. But from the start it quickly became clear that it had really involved the UN in a complex local African conflict as well as in the meddling of outside powers.

The Niemba ambush and UN authorisation of force

In November 1960, nine Irish soldiers were killed by Baluba tribesmen at Niemba. The irony was that the Balubas had not supported the Katanga secession and several of their villages were burned as a result by European mercenaries in Katangese service as well as by hostile tribes.

The attack on the Irish troops, in which 25 Balubas were also killed, was a result of them trying to keep open a bridge that the Balubas had destroyed, but may also have been the result of the tribesmen mistaking the white Irish troops for European pro-Katanga mercenaries.

The heavy casualties, as well as the manner of the deaths – the Irishmen were hacked and clubbed to death – caused great shock in Ireland, but also a certain amount of odd pride. The deaths in UN service appeared to show that Ireland was playing an honourable part on the world stage, carrying out a UN mandate.

Irish troops were deployed as part of a UN mandate to halt the secession of Katanga. But 9 of them died in an ambush with a local tribe.

However, the Congo crisis was only deepening. In December 1960 Patrice Lumumba, the pro-Soviet prime minister, was arrested by one of his generals – American backed Joseph Mobotu, handed over to the Katanga secessionist forces and killed. Now, as well as being a war over mineral resources, the Congo crisis became a front of the Cold War; the Soviets being outraged that their client had been ousted.

Jadotville in context

In February of 1961, the UN Security Council authorised its contingent in the Congo to ‘use force’ to end the Katanga secession, which ultimately triggered open hostilities between them and Katangese troops.

This was essentially the UN , in a manner that would be impossible today, trying to impose a solution that was not endorsed by either of superpowers – effectively for a short window playing an independent role.

Ireland’s neutral status gave it an advantage in this situation and an Irish officer Sean McKeown was made overall commander of the UN force in the Congo from 1961 until 1962.

In September 1961, Conor Cruise O’Brien, who, more so than his UN superior Dag Hammarskjold, took an aggressive position on the Katanga secession, ordered UN troops to seize control of Katangese mercenary positions in Elizabethville, the Katanga capital, dramatically upping the stakes in the UN-Katanga confrontation and causing fighting to break out between the two sides.

The offensive, ‘Operation Morthar’, was led by Indian troops under Major Raja, who behaved quite brutally, executing dozens of Katangese prisoners at the Elizabethville Radio Station. However in the days that followed the Katangese forces fought back. Three Irish soldiers were killed and more than 30 captured in the fighting in Elizabethville.

Irish troops found themselves besieged at Jadotville because Conor Cruise O’Brien ordered UN troops to seize Katangan positions in Elizabethville.

It was at this point that the Irish troops at Jadotville, part of the fourth Irish contingent to deploy to the Congo (35 Battalion), came under attack at the isolated post at the mining town of Jadotville. They had been deployed there, supposedly, to protect the lives of European civilians. But the Belgian population of Jadotville fervently supported the secession and were in fact vehemently hostile to the UN force.

The Irish company, 157 men under Commandant Quinlan, were surrounded by Katangese gendarmes and mercenaries and were left utterly exposed by the outbreak of fighting between the UN and Katanga.

A stiff four day fight ensued in which the Irish took no fatal casualties but may have killed about 300 Katangese troops. An Irish, Indian and Swedish UN force tried but failed to relieve them and the Jadotville garrison, under Quinlan, after running almost of out of ammunition and after prolonged negotiations, agreed to a ceasefire.

They were eventually disarmed and taken prisoner, after which they were taken into Katangese custody. Irish veterans spoke of the local women baying baying for their blood in revenge for the local men killed in the battle. The Irish troops were however protected by European mercenaries and later exchanged, along with other UN and Katangese prisoners, in a ceasefire deal by which the UN handed back the positions it had seized in Elizabethville.

All in all, Conor Cruise O’Brien’s attempted at ending the Katangan secession at a stroke had ended in a messy failure. For this, O’Brien was widely blamed and was forced to resign.

The Battle of the Tunnel

Dag Hammarskjold, the UN Secretary General died in a plane crash in the Congo during the ceasefire negotiations. Meanwhile though, the game had changed.

Now that the United States had removed the Soviet supporters in the central Congolese government, they supported the UN military mission in Katanga and Dag Hammarskjold’s successor, U Thant of Burma, ordered the UN troops to retake the secessionist province.

In December 1961, a further Irish Army contingent was involved in heavy fighting in the ‘battle of the tunnel‘ which was fought to re-open UN communications into Elizabethville. Three more Irish soldiers died in the fighting there. While Irish troops again acquitted themselves well, this was a United Nations force openly fighting on one side in a local civil war; not something a modern Irish peacekeeping force would allow themselves to be part of.

In Katanga the UN forces including the Irish openly fought on one side of a civil war.

While all this was going on, as well as the war between the Katangese on one side and the UN and central government on the other, tribal warfare and other factional strife was raging within the region due to the breakdown of law and order.

The Katangese secession was finally ended by another UN offensive, this time mostly Indian led, though an Irish battalion also participated, named ‘Operation Grand Slam’ in December 1962.

In December 1962, Tshombe, the leader of Katanga, signed an agreement giving up the aspiration to independence and shortly thereafter, he was exiled and UN forces successfully occupied the main Katangan towns, including Jadotville. The UN force remained deployed in the Congo until 1964.

After the end of hostilities, an Irish battalion was deployed to the town of Kolwezi, in the south of Katanga where they supervised the introduction of the Congo National Army (ANC). Ominously, the unit history described that latter as poorly paid, poorly led and poorly disciplined and described them (rather than the remnants of the Katangese forces who mounted the odd raid from across the border with Angola), as the main threat to civilian life.

A total of about 6,000 Irish soldiers served in the Congo between 1960 and 1964, of whom 26 lost their lives. Despite Irish losses, Taoiseach Sean Lemass and Frank Aiken remained insistent that Irish troops would fulfill the UN mandate. They, by all accounts, did the best they could, though often under-resourced, left without a clear mission and, at Jadotville as least, left unsupported in an impossible military position.

The Irish Army tends to view the Congo mission as a watershed, its coming of age as a modern force and establishing itself as a credible component for future UN peacekeeping missions. It is still deployed in UN service today, notably in the Golan heights between Syria and Israel and in Lebanon.

But regarding the Congo mission itself, the wider question remains, was it worth it?

The Katangese secession was ultimately quashed, but only to reincorporate Katanga first under the authoritarian Mobutu regime in the renamed Zaire and eventually the failed dysfunctional state of the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Mobuto took sole power after, with US and Belgian aid, putting down a communist backed uprising of Lumumba supporters in the east of the Congo in 1965.

During his rule, the American backed Mobuto banned all political parties, systematically looted the Congo’s natural wealth for his own enrichment and ran down the country’s infrastructure. A mutiny by the army over unpaid wages in the early 1990s made him vulnerable and with the Cold War over, the US now withdrew its support. He was toppled by Rwandan backed rebels led by Laurent Kabila in 1997.

An even more ruinous internal war followed from the late 1990s until the early 2000s as various African countries attempted to gain control over the Congo’s resources. This war led to the deaths of perhaps up to 5 million people, mostly by hunger or disease.

What, in political terms, did the UN mission in Katanga really achieve?

Today despite being fabulously wealthy in resources, Congo remains one of the poorest countries in the world. Foreign powers now, just as in the 1960s still hover, making sure they can extract the riches from the Congolese soil, but unlike the earlier period, the main players today are the Chinese. The idealistic premise of the likes of Conor Cruise O’Brien in the 1960s, that Africa would flourish if only it would be freed from predatory European powers, seems somewhat naive today.

All of which begs the question; would a Katanga independent from the Congo have been any worse than the states of which it was in fact part? And was the Irish military involvement there, without deprecating the bravery and commitment of the troops involved, really worthwhile?

If there is a lesson for today in the UN mission of 1960-1964 in the Congo, it is that force should only be applied for well thought out political objectives.