Revisiting Three Historical Paintings by Jack B. Yeats

Patricia Curtin Kelly looks again at three famous paintings depicting the Irish Revolution.

Irish artist Jack B. Yeats (1871-1957) is perhaps best known for his impressionistic paintings of early twentieth century Irish life.

However, he also produced three searing visual portrayals of the Irish Revolution; Bachelor’s Walk in Memory, The Funeral of Harry Boland and Communicating with Prisoners. The first represents a British Army shooting in Dublin in 1914, the latter two incidents of the Civil War.

In 1966, on the fiftieth anniversary of the 1916 Easter Rising, the Capuchin Annual published personal recollections, eye-witness accounts and photographic records of the events that took place at that time. The 1966 edition of the Capuchin Annual also included an article by Thomas MacGreevy (1893-1967) which was republished from its 1942 edition, presumably to complement its commemorative nature. In this article, MacGreevy who was director of the National Gallery of Ireland (NGI) discussed three historical paintings by Jack B. Yeats.

The Capuchin Annual was a well-read Irish institution which was published for forty-seven years, between 1930 and 1977, by the Capuchin Order in Dublin. It championed Irish writers and Irish artists and overall played a role in defining Irish culture in the early turbulent decades of the newly independent Ireland. Its distinctive brown cover, depicting St. Francis & the Wolf by the Irish artist Sean O’Sullivan (1906-64), was well-known throughout Ireland and abroad. In its heyday, it had a readership of 25,000 and Patrick Kavanagh (1904-67), the well-known Irish poet, described it as “a phenomenon of modern political Catholic Ireland.”

Jack B Yeats

Yeats was from a very well-known artistic family. His father was the portrait painter John Butler Yeats (1839-1922) and his brother was the Nobel Prize winning poet, William Butler Yeats (1865-1939). Two of his sisters, Susan Yeats (1866-1944) and Elizabeth Yeats (1868-1940) were involved with the Arts & Crafts movement in Ireland and set up Dun Emer Industries and Cuala Press which played an important role in the Celtic Revival of the early twentieth century.

Yeats was from a very well-known artistic family. His father was the portrait painter John Butler Yeats, his brother was the Nobel Prize winning poet, William Butler Yeats and two of his sisters, were involved with the Arts & Crafts movement

Although he was born in London, Yeats spent most of his childhood in County Sligo, a place which influenced him greatly. In 1897 he married a fellow art student, Mary Cottenham White, and they lived in England. He held his first solo show in London in 1897.

He returned to live in Ireland in 1910 and depicted mainly Irish subjects, ranging from street scenes, to boxing matches, to circuses, the races etc. He was a member of the Hibernian Academy and a Governor of the NGI. In 1913, Yeats learned Irish which was not an easy task for a man in his forties. He attended political meetings and heard Padraig Pearse (1879-1916) and other Irish patriots speak.[1] Therefore, he was not just interested in ordinary life but also politically aware.

In terms of painting, Yeats was probably the first and greatest interpreter of modern Irish life and landscapes. The three Yeats’ paintings discussed by MacGreevy are: – Bachelor’s Walk – In Memory, The Funeral of Harry Boland and Communicating With Prisoners and each has an interesting provenance.

Fr. Senan Moynihan OFM Cap. (1900-70), who was editor of the Capuchin Annual, was a great promoter of Irish artists. He bought these three paintings in 1941 from the Victor Waddington Gallery, at a cost of £30 each.[2] They became part of a collection of Yeats and other artists which were once held by the Capuchin Order.

Fr. Senan, played a significant role in the education of the Irish public in art through the Capuchin Annual and as a member of the Board of the NGI. His traditional Capuchin robe was a familiar sight at social and artistic gatherings. He purchased the three paintings, with the help of Lady Yarrow, so that he could reproduce them in the 1942 edition of the Capuchin Annual and with the express purpose of raising awareness of the work of Yeats the artist. Subsequently, the paintings hung in the Capuchin Annual office until the 1950s. [3]

Due to the increasingly precarious financial situation, at the Capuchin Annual, some remedial action was required. On 24 January 1954, Fr. Senan wrote to Fr. Colman Griffin OFM Cap., Provincial Minister of the Capuchin Order, recommending that the paintings held by the Order be sold.

He pointed out that he had “done something big for the artist concerned, Mr. Jack B. Yeats, and l am proud to be able to help to such an extent a great Irish artist, even though he is a Protestant, whose work was unappreciated.” Mr. Leo Smith, of the Dawson Gallery, Dublin was entrusted with the sale of the paintings and he offered them to the Irish Government for a sum of £2,700.

The Government was to contribute £2,000, provided they had the backing and additional £700 from the Board of the NGI.[4] Fr. Senan, who was a member of the Board, absented himself from these discussions for corporate governance reasons.

Following an emergency meeting of the Board, the proposal was rejected, on a vote of four to three, based on the NGI’s policy of not purchasing works by artists who were still alive. This was surely an extraordinary missed opportunity. It was extraordinary as well that MacGreevy, who was Director of the NGI and had a clear interest in Yeats the artist, did not seem to press the case with the Board.[5]

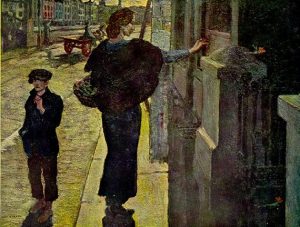

Bachelor’s Walk in Memory

Bachelor’s Walk – In Memory was painted in 1915.[6] MacGreevy described this painting as “one of the most beautiful and moving pictures the artist ever painted.”[7] In 1957, he tried to get Eamon de Valera (1882-1975) to persuade Lady Dunsany, who had subsequently purchased the painting, to donate it to the Government, but to no avail[8][9]

Bachelor’s Walk – In Memory was painted in 1915.[6] MacGreevy described this painting as “one of the most beautiful and moving pictures the artist ever painted.”[7] In 1957, he tried to get Eamon de Valera (1882-1975) to persuade Lady Dunsany, who had subsequently purchased the painting, to donate it to the Government, but to no avail[8][9]

In 1990, the painting was stolen and only recovered in 2007 after it was spotted in a Sotheby’s publication in London. Subsequently, in 2009, Lady Dunsany placed the painting on long-term loan to the NGI. Before that, in 1971, it was exhibited at the NGI’s centenary exhibition on the work of Yeats and was also used as the cover image for that brochure.

The painting depicts the aftermath of an incident, in 1914, when a detachment of the King’s Own Scottish Borderers intercepted a large party of Irish Volunteers, returning from Howth, where they had collected a supply of arms.

A hostile crowd pursued the soldiers as they were returning to barracks. Major Alfred Haig asked the crowd to disperse. When they did not, the soldiers opened fire, killing four people and injuring thirty-two others, all mostly innocent bystanders who were watching the military parade pass by.[10] While Yeats did not witness this incident, he visited the scene the following day and made a sketch on the spot.

It has been argued that this is an “iconic” and “symbolic” painting. The historian Turtle Bunbury said that Padraig Pearse considered the “Bachelor’s Walk massacre” to be an iconic moment in the struggle for independence and “Remember Bachelor’s Walk” became a rallying cry.[11] The incident highlighted double standards whereby Unionists could arm while Home Rulers were shot at for the same reason.

The painting depicts the aftermath of an incident, in 1914, when a detachment of the King’s Own Scottish Borderers opened fire pn a crowd in Dublin, killing four people and injuring thirty-two others.

The painting itself is one of Yeats’ earliest and most significant oils. It depicts a flower girl in the act of placing one of her flowers on the spot, on Bachelor’s Walk, where one of the casualties was shot. In the background, one can clearly see St. Augustine & John’s church and Christ Church cathedral which firmly sets the location. While the girl is engrossed in the act of placing her flower, life in the city is clearly going on behind her. One can see men lounging on the quays of the river Liffey, people passing over the Ha’penny Bridge and a horse and cart passing by.

There is nothing grandiose about the picture although MacGreevy said that the flower girl could be an “Hellenic model at an altar.”[12] Ernie O’Malley (1897-1957), the IRA and anti-Treaty activist, described the picture as “a national icon and symbol.”[13]

In addition, the art critic T.G. Rosenthal, says that it is “an archetype representing all Irish womanhood mourning the loss of their men.”[14] The journalist and art critic Bruce Arnold maintained that Yeats had no interest in politics or nationalism. He said that Yeats was “expressing the instant of human emotion and not the moment of national feeling.”[15] Christopher Baran argued that MacGreevy presented a biased account of the events of 1914 as he gave his readers an image of the Irish as innocent victims and the British as transgressors.[16]

It is more likely that the deaths and injuries were due to an over-hasty response, to a largely hostile crowd, rather than any pre-meditated action Yeats probably painted this picture as a tribute to the humanity of the act by the flower girl rather than as any political statement. The picture focuses the viewer on the consequences of conflict on ordinary people rather than on the heroic or idealistic nature of the struggle for national freedom.

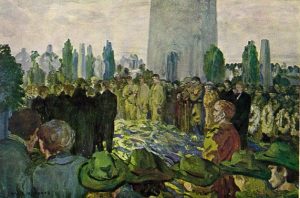

The Funeral of Harry Boland

Painted in 1922, The Funeral of Harry Boland is part of the Niland Collection.[17] This was founded by Nora Niland, the county librarian in Sligo, who started collecting art in the 1950s. Mrs. V. Franklin bought it from the Capuchin Order in 1959, and gifted it to the Niland Collection.[18] This picture was exhibited in the RHA in 1923, under the title A Funeral, and was brought to public attention through the MacGreevy article in 1942.

Painted in 1922, The Funeral of Harry Boland is part of the Niland Collection.[17] This was founded by Nora Niland, the county librarian in Sligo, who started collecting art in the 1950s. Mrs. V. Franklin bought it from the Capuchin Order in 1959, and gifted it to the Niland Collection.[18] This picture was exhibited in the RHA in 1923, under the title A Funeral, and was brought to public attention through the MacGreevy article in 1942.

Harry Boland was a leading anti-Treaty Republican, killed during the Civil War.

The painting depicts the funeral of Harry Boland (1884-1922), a member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood and subsequently a member of the Dail. He was killed, in controversial circumstances, in Skerries, County Dublin. It is said that this painting is the only public record of Boland’s funeral as cameras were confiscated at the gates of the cemetery.[19] Boland was a close friend of both Michael Collins (1890-1922) and of Eamon de Valera, respective leaders of the pro and anti-Treaty sides of the Treaty split in 1922.

While he opposed the Treaty, he endeavoured to be a peace-maker between the two factions but took the anti-Treaty side in the Civil War and was shot and mortally wounded during his arrest by pro-Treaty troops. MacGreevy said that Boland was unarmed at the time of his arrest and implied that he was mortally wounded by over-zealous Free State personnel.[20]

Both sides in the Civil War lost notable members, with brother fighting brother and father fighting son. By the time MacGreevy wrote his article, in 1942, de Valera and Fianna Fail were in power which is an example of democratic politics at work in a newly emerged state.

The painting depicts the scene at the the Republican plot at Glasnevin Cemetery, Dublin where Boland was buried. The round tower, which commemorates Daniel O’Connell – The Liberator (1775-1847), dominates the background. Interestingly, Yeats focuses on the crowd rather than on Boland’s coffin.

The viewer is looking towards a freshly dug grave which is bedecked with flowers. On the right-hand side, members of Cumann na mBan, the women’s Republican organisation, are looking on and some of them are carrying wreaths of flowers.

Republican men, some of whom are holding rifles, are also looking on with bowed heads. Despite the risks to themselves, they are reported to have fired a salute of three volleys in memory of their dead comrade.[21]

A group of priests, dressed in black, are on the left-hand side of the picture. The leader of the IRA, on the lower right-hand side, is staring directly at the coffin. Heads of other onlookers can be seen in the foreground, including two young men who seem to be chatting which is out of kilter with the general air of sombreness. MacGreevy maintained that this picture marks the complete and masterly statement in terms of modern Irish life of the great European tradition of historical painting.[22]

It appears the artist is sympathetic to what is going on rather than merely a recorder of the event. The picture also evokes a spirit of the nobility of sacrifice and the sense of reverence for a lost patriot. For this reason, it is a significant memorial to all those who fell during the troubled times of the Civil War.

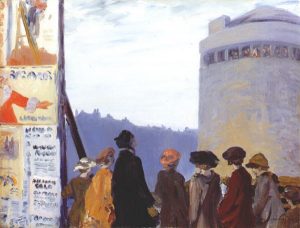

Communicating with Prisoners

Communicating With Prisoners,[23] painted in 1924, is also part of the Niland Collection and was bought from the Capuchin Order in 1959. In 2012, it was selected by a national panel as one of ten Irish paintings, on which the public was invited to vote in order of preference, for the nation’s Favourite Irish Painting.

Communicating With Prisoners,[23] painted in 1924, is also part of the Niland Collection and was bought from the Capuchin Order in 1959. In 2012, it was selected by a national panel as one of ten Irish paintings, on which the public was invited to vote in order of preference, for the nation’s Favourite Irish Painting.

While this painting was not the top favourite, nevertheless, the competition drew attention to a relatively unknown work by Yeats. It recalls the role of women in the struggle for Irish independence. This was no less than that of their male counterparts, yet it is largely unsung and unrecorded. It is surprising, therefore, that Yeats choose this as a subject and that MacGreevy choose to include it for discussion in his article.

The painting depicts a group of seven women and one boy, listening and calling up to a group of republican women prisoners, who are high up in a tower at Kilmainham Jail. They were jailed, by the Free State government, for their involvement in the Civil War. One of the jailed women seems to be leaning out of a window to either shout more loudly, or to hear more clearly, the news of the day from friends below.

The painting depicts a group of seven women and one boy, listening and calling up to a group of republican women prisoners, who are high up in a tower at Kilmainham Jail.

The group on the outside are standing, in the foreground, with their backs to the viewer. They are well dressed in stylish coats and are wearing a variety of colourful and fashionable hats. The imposing bulk of the dark and forbidding tower of Kilmainham Jail, on the right-hand side, is balanced by a bill-board with colourful posters, on the left-hand side.

One shows a Santa Claus which would seem to indicate that it was around Christmas time when the event took place. In the distance, one can see a row of grey eighteenth century Dublin houses under a cloudy sky. Overall, the painting shows the solidarity between the women. It also points to the contrast between the “free” women on the outside and the “jailed” women on the inside.

MacGreevy said that female Volunteers showed “a magnificent lack of respect for the silliness of many man-made rules.” [24] The female prisoners in the painting have broken the windows of their jail, so that they could communicate with their sisters below on the outside. MacGreevy also seemed to give a romantic nobleness to female depictions, such as “female grace,” which was perhaps not intended by the artist.

While many women were taken prisoner, by both the British and to a far greater extent by the Free-State authorities, there were no “republican heroines” as none of them were executed. Arnold maintained that a “significance has been attached where none was necessarily intended.”[25]

Christopher Baron outlined that women prisoners also went on hunger strike. For example, in 1923, six republican women held in Kilmainham Jail, including the Irish revolutionary and suffragette Maud Gonne McBride (1866-1953), went on hunger strike.[26] For many years, McBride was the romantic obsession of William Butler Yeats and a great influence on his poetry. Perhaps this is the connection that prompted his brother to paint this subject matter? It is also a rare and unusual depiction of life in the early days of the Free State. Overall, the painting is a reminder of the important role women played, both during 1916 and after the Treaty

Conclusions

The style of these three paintings is very contrasting. For example, Batchelor’s Walk – In Memory could be described as traditional and rather nostalgic and is finely painted with muted colours. The Funeral of Harry Boland and Communicating with Prisoners are both painted in a rather naïve, linear style with a clear horizon on the background and are reminiscent of Yeats’ work for the Cuala Press broadsheets. None of these paintings, however, give any hint of the vibrant and colourful impressionistic style that would become synonymous with Yeats in later life.

Fr. Senan and MacGreevy brought together three paintings, by a contemporary Irish artist, which depict incidents from a new and changing Ireland. While the specific incidents may seem to be insignificant, in the context of the more heroic deeds of the time, nevertheless they highlight the humane and tragic elements that occurred as part of our history. Innocent people got caught up in events and a gesture of respect was warranted. Personal friendships suffered because of civil war but people were properly commemorated when they died. Friendship and support were important, even where there was a separation

MacGreevy said that “Jack Yeats lifted the art of painting in Ireland on to a plane of heroic tragedy it had never before attained .” [27] Arnold said that although they have “an aura of nationalism” the “so-called political paintings have been misrepresented.” Arnold went on to say that Yeats was “not necessarily dealing with the political event nor taking a side in it. In any assessment of his work it is the human side that comes first.”[28] The art historian John Turpin said that Yeats “often depicted the larger historical tragedies through a small poetic detail.”[29] The art critic and biographer Hilary Pyle maintained that “Yeats’ patriotism was mature and of a deeply idealistic nature.”[30]

In these three paintings, Yeats is a recorder of the events for posterity rather than bestowing any great comment on them. He is showing the impact of national events on ordinary people, without a sense of the heroic. As Turpin said “paintings of historical subjects can have a political consequence even if intended as pure reportage.![31]

By painting ordinary people, in ordinary surroundings and carrying out ordinary activities, Yeats has also added to the self-worth of the country.

Historical paintings are regarded as the highest form of art in classic academic theory. They usually tell a story with a moral or idealistic purpose. Yeats has understood this purpose in these three paintings. As an Irish artist, he shows a sympathy and sense of identity with the ordinary people of Ireland and has left a legacy that maintains a rare record of the three events.

Apart from photographs, there are very few paintings of the 1916 Easter Rising period. While these three paintings are not depicting events that happened during the Rising, nevertheless they show an incident before, which was influential, and two incidents afterwards, which occurred because of the Easter Rising. By painting ordinary people, in ordinary surroundings and carrying out ordinary activities, Yeats has also added to the self-worth of the country.

It is to their credit that both Fr. Senan and MacGreevy recognised the talent and humanity in Yeats’ paintings, at a very early stage, and ensured his work was brought to the attention of the general public. In this year of commemoration, 2016, the three paintings are an important reminder of these events and their place in our history. All three paintings are currently on view at the Creating History: Stories of Ireland in Art exhibition on view at the National Gallery of Ireland until the 15 January, 2017.

Patricia Curtin-Kelly is a Cork born art historian and lives in Dublin. She holds an M.A. (hons.) in Art History from University College, Dublin as well as an M.Sc. in Human Resources Management from Sheffield Hallam University. Her book An Ornament to the City – Holy Trinity Church and the Capuchin Order was published by the History Press Ireland in 2015.

References

[1] T.G. Rosenthal, “The Art of Jack B. Yeat,s” Andre Deutsch, London 1993l – p.26

[2] Peter Sommerville-Large, “The Story of the National Gallery of Ireland (1856-2006),” National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin. 2006 – p.359

[3] Bruce Arnold, “Jack Yeats” Yale University Press, New Haven & London, 1998 – p.320

[4] Peter Somerville-Large, – p.54

[5] Peter Sommerville-Large – p. 359

[6] National Gallery of Ireland, Merrion Square Dublin

[7] Thomas MacGreevy, “Capuchin Annual 1966” Dublin – p.396

[9] Peter Sommerville-Large – p.359

[10] Turtle Bunbury, “Death on Bachelor’s Walk – 27-07-1914” http;//www.turtlebunbury.com/history/press_irishhistory_irish_bachelors_walk.htm 20/10/2015

[11] Turtle Bunbury

[12] Thomas MacGreevy – p.396

[13] Bruce Arnold, p.193

[14] T.G. Rosenthal, – p.26

[15] Bruce Arnold, p.193

[16] Christopher Baron, “Bachelor’s Walk; In Memory” for the Thomas MacGreevy Archive, 2003

[17] The Model Arts and Niland Gallery, Sligo

[18] Donal Tinney Ed., “Jack B. Yeats at the Niland Gallery, Sligo” Niland Gallery, Sligo County Library, 1998

[19] Bruce Arnold, p. 194

[20] Thomas MacGreevy – p.397

[21] Thomas MacGreevy – p. 397

[22] Thomas MacGreevy – p.397

[23][23] Model Arts & Niland Gallery, Sligo

[24] Thomas MacGreevy – p.398

[25] Bruce Arnold, – p. 195

[26] Christopher Baron, “Communicating with Prisoners,” for the Thomas MacGreevy Archive, 2003

[27] Thomas MacGreevy – p.396

[28] Bruce Arnold – p. 55

[29] John Turpin, “Irish History Painting” Irish Arts Review, Dublin 1989-90 – p.242

[30] Hilary Pyle, “Jack B. Yeats – A Biography” Routledge & Kegan Paul, London. 1970 – p.119

[31] John Turpin – p.233