Book Review: Heroes of Jadotville: The Soldiers’ Story by Rose Doyle

Published by New Island Books, Dublin, 2016

Published by New Island Books, Dublin, 2016

ISBN: 978-1848404885

Reviewer: Gordon O’Sullivan

“If you have been killed you have a victory, but if you save your men and have a good defence, it is a defeat.”

It is perhaps not surprising that the events recounted in the Heroes of Jadotville eventually ended up in a film, it has all the elements demanded of a classic war movie. There’s the courageous and charismatic commander backed by resourceful troops who somehow maintain a cheery disposition despite dwindling supplies while dug in against overwhelming odds deep in enemy territory and cut off from the main army. The only thing missing from this war movie was a final scene of victory.

What transpired instead was a painful surrender compounded by political and institutional contempt that completely obscured the sterling efforts and heroic courage shown by those 156 Irish soldiers during the 1961 six-day battle at Jadotville in the Congo.

Rose Doyle’s revised and updated book recounts the Siege of Jadotville, a bloody battle fought in a predominantly Belgian mining town in the breakaway Congolese province of Katanga in September 1961

Rose Doyle’s revised and updated book, it was first published ten years ago, recounts the Siege of Jadotville, a bloody battle fought in a predominantly Belgian mining town in the breakaway Congolese province of Katanga in September 1961. 156 lightly armed soldiers of A Company in the Irish 35th Battalion under the command of Commandant Pat Quinlan, a Kerry man who “grew to giant size in every man’s eyes,” fought off approximately 4,000 heavily armed Katangan Gendarmerie and mercenary troops for six days until their eventual and inevitable surrender.

The battle takes up just one half of the Heroes of Jadotville, however, focusing as well on the shameful treatment of the Irish soldiers by their Katangan captors and their Irish commanders both in the Congo and back home in Ireland.

Doyle is crystal clear on why the Irish soldiers were in Jadotville in the first place. The UN had been invited into Congo to prevent the resource-rich province of Katanga from seceding. She contends that A Company were purposely sent 80 miles away from their base camp at the connivance of the Belgian government, they were supporting the secession, to be taken hostage by the Katangan government for use as a bargaining chip with the UN. The Irish troops were ostensibly sent to Jadotville to protect Belgian colonists there but on arrival it was clear that their protection was completely unwelcome.

At the same time, again Commandant Quinlan and his troops were in the dark, the UN was about to launch a punitive expedition, Operation Morthor, against the Katangan government thus placing the Irish soldiers deep in what would be enemy territory. A Company arrived in Jadotville ten days before the battle, armed with just mortars, machine guns and shoulder-launched anti-tank guns. They would face considerably heavier ordnance from the Katangans during the battle ahead.

Doyle recounts the ensuing battle in an exhilarating and almost minute-by-minute account.

Doyle recounts the ensuing battle in an exhilarating and almost minute-by-minute account. From the very start Quinlan ordered “every man in this company will dig trenches”, a wise move considering what was to come. The soldier’s water and electricity were cut off and shopkeepers and hoteliers refused to serve them. Soon the roads out of Jadotville were blocked and there was intelligence of Katangan reinforcements arriving in the town.

A clash between the Irish and the Katangans wasn’t long in coming, beginning appropriately for this God-fearing bunch of men during morning mass on 13 September. The Irish troops were in for six days of consistent heavy machine gun and mortar fire as well as a Katangan airplane which machine-gunned and bombed their positions. Despite this sustained bombardment, the Irish troops fought back with a ferocity that took the Katangan Gendarmerie and their mercenary advisers completely by surprise, prolonging the siege and killing hundreds of Katangans.

Their tremendous courage and the professionalism shown by A Company was despite the “antiquated equipment, armoured cars that you could probably shoot arrows through” and “uniforms made of bull’s wool and hobnailed boots” that they were supplied with. In addition, Quinlan and his men had to deal with woefully inaccurate intelligence provided by Irish headquarters on the rare occasions they could get it due to poorly performing radios.

Even when the radio operators got through, their messages were intercepted by the Katangans and the content, in Irish, was translated for their enemy by two Connemara man working in the local mine. The Katangans also tried all sorts of dirty tricks like bringing up ambulances containing machine guns and calling Quinlan to the telephone for negotiations and then shelling the house where the telephone was located.

A Company held on but food was running down, the men were reduced to eating Jadotville Stew made up of anything and everything edible, water was running out, ammunition was low and UN reinforcements were stuck 18 miles away on the wrong side of a heavily defended bridge. Amazingly there were no fatalities on the Irish side during the entire siege.

Despite invaluable assistance from the few friendly colonists in Jadotville including the wonderfully doughty Madame Lamonfagne, an elderly Belgian lady who refused to leave even when her house was under attack, Quinlan began to think the unthinkable. He realised that without a realistic chance of reinforcements or resupply a permanent ceasefire was his only option despite the Irish remaining firmly undefeated on the field of battle. “There was a choice of saving my brave men by that; there was only certain death in any future action…it could not be justified by any standards: moral, military or political”.

He radioed the Irish HQ to let them know his decision and agreed joint patrols with Katangan forces and to store their weapons away. The Katangans quickly took advantage of the ceasefire and took the Irish soldiers into captivity. A Company’s conditions deteriorated quite badly during their five weeks in captivity but Quinlan kept the men’s morale up. Self-defence classes were organised, Molotov cocktails were made to defend themselves, some of the men listened to the All-Ireland final on the radio. Their hopes of being released were raised and dashed on several occasions but finally in late October, Quinlan led his men out of captivity when they were turned over to UN forces.

On returning to the bosom of their comrades, in some ways their battle had only begun. It was soon clear that the reasons for their surrender had not been appreciated or approved of by some in the Irish battalion, there was considerable tension between the companies.

A Company were recompensed for their bravery by being billeted in a large cow-byre with a leaky roof. Incredibly the uninjured soldiers were put almost immediately back in service and were soon involved in the biggest Congo battle of the UN campaign at the Tunnel, a strategic railway underpass in Elisabethville. Finally, on 19 December 1961, all the remaining members of A Company flew home but they didn’t fly home to a heroes’ welcome.

Commandant Quinlan was convinced that some of his superiors thought he and his men should have died with their boots on at Jadotville rather than surrender.

Commandant Quinlan was convinced that some of his superiors thought he and his men should have died with their boots on at Jadotville rather than surrender, “there is a deliberate policy now to decry the action at Jado.” When Quinlan handed the radio log of the battle to a RTE reporter to bring back to his wife, it disappeared en transit.

All of the men that Quinlan proposed for medals were turned down by the Irish Army medals board. Quinlan and his men always felt they were never properly recognised for their brave service in the Congo but were in fact stigmatised by what had happened and their military careers consequently curtailed.

The pace of the first section of Heroes of Jadotville which focuses on the action of the Siege is frenetic and wholly absorbing. Doyle’s use of personal testimony and the radio signals in particular put the reader right in the middle of the battle. The author, who is Commandant Pat Quinlan’s niece, uses her insider knowledge and personal connection to the story to great effect. By the time, Quinlan is asked by Irish HQ on the radio, “are you deserting the men?” you are so attuned to the men’s viewpoints that you’re likely to feel personally affronted by the question.

The author manages to balance that relentless pace with lovely personal snippets about the individual officers and men and the reader gets a good sense of the Irish soldiers; God-fearing men from poor West coast backgrounds who maintained a devotion to both their heavenly Lord and their temporal master, Commandant Quinlan.

Rose Doyle’s book is an enthralling, passionate affair, but here is little attempt to provide alternative political or military views and little use of more objective sources.

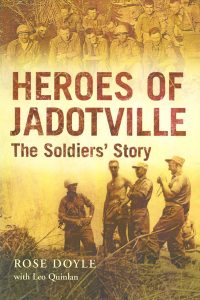

There are some lovely incidences of the soldier’s humour in extremis too, for example when the Swedish interpreter expressed doubts about understanding Quinlan’s robust Kerry accent, Lieutenant Joe Leech told him, “We don’t understand him either.” The photographs contained in Heroes of Jadotville are also a real strength. After such an exhilarating opening section, the second half of the book is inevitably less involving. The aftermath of the battle at Jadotville and the long battle for recognition is less a terrifying battle and more a steady slog for acceptance.

Rose Doyle’s book is a passionate affair, the author clearly feels the men of Jadotville should be praised for their service in the Congo and not forgotten. She also feels that there has never been an official reckoning for the army brass who stymied the recognition of the men of Jadotville.

That passion is one of the key strengths of this book but at times it’s also a weakness. There is little attempt to provide alternative political or military views and little use of more objective sources. The personal letters and testimonies are on occasion overused or the extracts used are overly long and Quinlan’s thoughts and feelings are reproduced without much analysis or context by the author.

Those are minor cavils however as this book is a worthy memorial to the heroism of these Irish soldiers who were brutally airbrushed from the Defence Forces’ role of honour when their bravery demanded full recognition. Thankfully that has changed somewhat in the last few years.

A portrait now hangs in the UN Training School at the Curragh Camp of Commandant Quinlan, there’s a commemorative plaque to A Company in Custume Barracks in Athlone and recently a wreath-laying ceremony took place at the National Museum Collins Barracks in memory of the men who fought at Jadotville and have subsequently died including Pat Quinlan. The ceremony was part of what will now be an annual Jadotville Day for Defence Forces veterans, a small token of remembrance for what they went through in 1961.