Martin McGuinness 1950-2017

By John Dorney

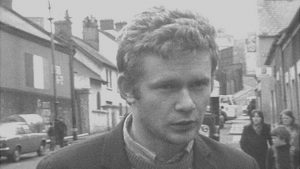

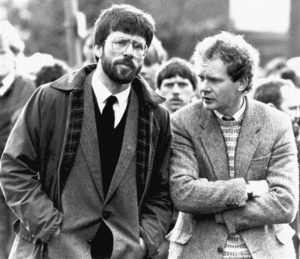

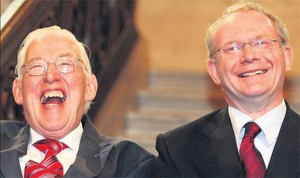

Martin McGuinness always cut a striking figure. From a youthful, blonde shaggy haired Provisional IRA commander in Derry in the early 1970s to the doughty, curly haired IRA and Sinn Fein leader of the 1980s, to the ‘chuckle brother’ Deputy First Minister of Northern Ireland in the 2000s, McGuinness over nearly five decades represented the changing face of Irish Republicanism.

When being mischievous, his eyes would quietly dance even as his mouth remained impassive. In person, those who met him relate that he was often warm and witty. Even among those who hated and feared the Provisional Republican movement, McGuinness, unlike his close colleague Gerry Adams, often inspired a certain personal affection. This was despite the fact that McGuinness, unlike Adams, openly and proudly admitted to having been a leading member of the IRA.

There was also, however, a much darker side to McGuinness’s personality. Those who crossed his path in Derry, spoke of a ruthless, feared man, who could order a death as calmly and coldly as a chess player making a move. In an interview with journalist Peter Taylor in the 1980s on the phenomenon of ‘supergrass’ IRA informers, McGuinness suggested that all such men should recant their testimony or if not face the consequences.

The consequences, Taylor suggested, were death. ‘Death, certainly’ McGuinness replied without missing a beat.

McGuinness, after his death earlier this week, has commonly been painted in the media as a ‘man of violence who became a man of peace’. McGuinness did indeed rise to the top of the armed Republican movement during the Northern Ireland conflict and eventually led it through the ceasefires of the 1990s and the peaceful political process of latter years. The rather facile ‘man of war/man of peace’ frame, however, does no justice to the complexity of the man or to his trajectory as a militant Republican leader.

From ‘sixty-niner’ to senior Provisional

McGuinness, unlike Gerry Adams, did not have deep family ties to the Republican movement dating back to the early twentieth century.

Rather, like many young men from places like Belfast and McGuinness’s native Derry, he was drawn into militant Republicanism as a result of his experiences on the streets in 1968-69, when the Northern Ireland Civil Rights movement for Catholics sparked off an increasingly deadly series of riots between police and protestors. McGuinness was in Republican slang, ‘a sixty niner’, i.e. a product of the ‘Troubles’ and not of Republican ideology.

Prior to the explosion of 1968-69, McGuinness, a native of the working class Catholic Bogside area of Derry, from a family where ‘politics was never discussed’ and ‘the IRA was a strange thing’ had been working as a butcher’s apprentice. Certainly he was aware of the discrimination against Catholics and Irish nationalists in Northern Ireland, but prior to 1968 he was not burning with anger about it. He was interested in both Association and Gaelic football, and was brought up a pious Catholic. He was later to say, ‘if I believed the struggle was wrong from the point of view of being a Catholic I would not be part of it’.[1]

It was the experience of conflict, not family history or ideology that drew McGuinness into the IRA.

According to his own accounts, he marched in the initial Civil Rights marches, was increasingly radicalised by the violent treatment marchers were given at the hands of the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) and eventually, sometime after the huge riot in Derry known as the ‘battle of the Bogside’ in August 1969, and after the British Army was deployed to the city, he joined the IRA. [2]

In 1972 he told a local journalist, ‘It seemed to me that behind all the politics and marching, it was plain as daylight that there was an Army in our town, in our country and that they weren’t there to give out flowers. Armies should be fought by armies.’ His political views were not complicated, ‘I want a United Ireland where everyone has a good job and enough to live on.’[3]

The IRA was split over the events of August 1969, in which 8 people were killed in rioting in Belfast and Derry, with the more gradualist ‘Official’ wing favouring caution and a more militant splinter group, ‘the Provisionals’ emerging, favouring immediate armed action against the British Army and the ‘Orange state’.

Since, in the early days, there was no significant Provisional presence in Derry, McGuinness initially joined the Official IRA and stayed there for some months, but he rapidly graduated to the more militant group, who were soon to absorb sole proprietorship of the name of IRA.[4]

In 1971, the ‘Provos’, began their armed campaign against the British Army. By the time of the introduction of internment without trial in August of that year, they had killed only one British soldier in Derry, but by the end of that year, fuelled by communal rage in Catholic neighbourhoods at the imprisonment without trial of their menfolk, another ten British soldiers had died at their hands in the city, followed by 18 more the following year.[5]

It is hard to determine McGuinness’s exact role in these events, but it is certain that the 21 year old rose rapidly within the ranks of the Provisional IRA in Derry. By the time of ‘Bloody Sunday’ in Derry in January 1972, McGuinness was recalled by many to be the leader of the Provisionals in the city, though he himself testified that he was second in command.[6]

Clearly, the young McGuinness had leadership skills. A British Major who fought him and his men around that time thought he was ‘excellent officer material’.[7] Derry activist Eamon McCann wrote that in the wake of Bloody Sunday, ‘the Provos under Martin McGuinness managed to bomb the centre of Derry until it looked as if it had been hit from the air, without causing civilian casualties’. He is also rumoured to have been behind the Claudy bombing which killed nine civilians. [8]

So prominent was he already by the summer of 1972 that he was included, at the callow age of 22, in a Provisional IRA negotiating team that met directly with the British government during a short-lived IRA ceasefire of that year. Predictably, talks went nowhere. McGuinness recalled that the IRA team simply demanded ‘a declaration of intent to withdraw’. [9]

Prison and after

Not long after the 1972 ceasefire broke down, McGuiness was arrested south of the Irish border in a car full of high explosives and ammunition. As was standard IRA procedure at the time, he refused to recognise the legitimacy of the court, as for the IRA both Irish states were illegitimate, British imposed entities, and was imprisoned from early 1973 until November 1974.

When he had served his conviction for the first offence, he was sentenced to another for IRA membership. On his conviction, McGuinness made no bones about his paramilitary affiliation, declaring he was ‘very, very proud’ to be a member of the IRA.[10]

When he was released from prison, the Provisional movement was in some turmoil. After a ceasefire from December 1974 to January 1976, in which they hoped but failed to get political concessions from the British, the IRA was debilitated by internecine feuding and arrests and its reputation blackened, even among its supporters, by a series of openly sectarian killings.[11]

McGuinness rose rapidly in the Provisional movement and by the late 1970s was IRA Chief of Staff

The upshot of these events was that power within the IRA was seized by a younger generation of Northern men, led by Gerry Adams, Danny Morrison, Ivor Bell, and McGuinness himself, who ousted the southern based leaders Ruairi O Braidaigh and Dathi O Connaill, as well as older Northern activists such as Billy McKee and Joe Cahill.

McGuinness and the new generation of IRA leadership split the organisation operationally into two parts, Northern command and Southern Command, and conceived of a long term strategy of low intensity violence known as the ‘long war’, which it was thought, would ultimately drive the British from the North and force the unionists to accept a united Ireland.

McGuinness was made head of the Northern Command in 1976 and later Chief of Staff of the entire organisation from 1978-82, in around 1985 again serving as head of the Northern Command.[12]

In 1986, McGuinness was to the forefront in a long path towards compromise on what had been sacrosanct Republican principles, abandoning the ban on entering the Dáil, or parliament of the Republic of Ireland, if elected. This caused the older leadership who had been side-lined in the late 1970s, to split off and leave the movement in protest. McGuinness maintained at the Sinn Fein Ard Fheis that the initiative would not meaning ‘running down the armed struggle’.

Indeed, McGuinness had not become a moderate. He publicly articulated and defended the ‘long war’ strategy in public on many occasions. In 1988 for instance, he told Republicans at a commemoration for 8 IRA members killed at Loughgall the year before;

‘I believe that the… Irish Republican Army have got the capability, the ways and means of bringing about the defeat of the British forces… But in saying that, I am not saying the IRA have the ability to drive every last British soldier out of Derry, Belfast, Armagh, Antrim Down or anywhere ese. But they have the ability to sicken the British forces of occupation’.[13]

As the 1980s went on, the Republican movement developed a dual political and military strategy of running for election in Sinn Fein while at the same time keeping up the IRA campaign. McGuinness, while running for election himself, was forthright in insisting that it was the IRA that would play the vital role.

From War to Peace

The standard media narrative goes that McGuinness along with Adams, grew disillusioned with the use of force as the Northern conflict dragged on into the late 1980s and embarked on a series of back-channel discussion with the British and Irish governments to bring the conflict to an end.

One version has it that it was the Enniskillen bomb of 1987, an attack on mourners at a Remembrance Day service that killed 12 civilians and wounded 63 that moved McGuinness towards pacifism. Certainly the bomb brought great discredit to the ‘armed struggle’; but the Derry man was not known for his squeamishness.

McGuinness may have pioneered a localised peace process in Derry in the early 1990s.

Just as likely as a change of heart on McGuinness’s part was a tactical re-think. The IRA had planned major escalation of the conflict, with heavy weapons imported from Libya, nicknamed the ‘Tet offensive’. When this failed to come off, due to some of the arms shipments being intercepted by the southern Irish authorities, it opened the prospect that IRA violence would never effect political change in the status of Northern Ireland. It was time to try a different approach.

One of the more intriguing, and probably unprovable, assertions about the early peace process is that McGuinness, on his own initiative, presided over a localised version of it in his native Derry, years before the official IRA ceasefire of 1994. Journalist Ed Moloney writes that, owing to mediation by a local Quaker family, an unofficial de-escalation agreement was reached between McGuinness and the British Army garrison in Derry, reducing violence there by 60% from 1989 to 1993.[14]

Some disillusioned Republicans, now convinced that McGuinness was traitor or even a British spy, allege that he systematically ran down the armed campaign deliberately at the same time that he was still sending out young militants to kill and be killed. Are these accusation really credible? Violence certainly tailed off in Derry in the late 1980s and early 1990s, but it never stopped altogether.

In any case, it is certainly true that McGuinness’s authority among veteran IRA fighters gave the ceasefire of 1994 and the subsequent unarmed Sinn Fein strategy a prestige it would not otherwise have had. He, along with Gerry Adams, headed the Sinn Fein team during the negotiation of the Good Friday Agreement in 1998. In this agreement, the two jettisoned several articles of faith for Republicans, recognising the legitimacy of Partition until the majority in the north voted otherwise and accepting their places in a new Assembly in Northern Ireland.

On the other hand, they secured the release of Republican prisoners, the disbandment of the RUC police force and in effect a bi-national status for citizens of Northern Ireland. Support for Sinn Fein subsequently surged on both sides of the border.

Politician

McGuinness brought to parliamentary politics much of the steel he had brought to armed activities in the IRA.

In the first sitting of the new Northern Ireland Assembly in July 1998, a succession of unionist speakers denounced the entry of ‘unreconstructed terrorists’ into government. Sammy Wilson for example of the DUP stated,

‘IRA/Sinn Fein Members talk about taking steps into a new future. They tell us to think of the people – the very people they have been shooting and bombing for 30 years. Many who sit on the Benches opposite were involved in such activities not just at a distance but directly, but we have heard not one word of apology. They have given no indication that they are sorry, no indication of acceptance that what they did was wrong. Indeed, they arrogantly portray their position as having been justified.’

While Gerry Adams appeared somewhat taken aback, McGuinness responded like the street-fighter he was, setting his penetrating gaze on Wilson and retorting of anti-Agreement unionists,

They have spoken long enough. They have to face up to the reality that there is going to be change, that the change will be fundamental, that they cannot prevent our involvement in this body, or the Executive, that they cannot prevent the establishment of all-Ireland bodies with executive powers, that they cannot prevent the equality agenda, that they cannot prevent promotion of the Irish language, that they cannot prevent the creation of a new police service and that they cannot prevent the release of political prisoners. That is the reality.[15]

If McGuinness was unapologetic about his past, he was also determined to make the Agreement work. He was made Minister for Education in the first Northern Ireland Executive, despite having finished school himself at the age of 15.

McGuinness was no convert to pacifism and was unapologetic about his past use of violence.

By January 2007 further negotiations having brought Ian Paisley’s Democratic Unionist Party into the Agreement, McGuinness became Deputy First Minister, first to Paisley and then to his successors Peter Robinson and Arlene Foster. McGuinness’s warm personal relationship with Ian Paisley led to the two being christened the ‘chuckle brothers’.

As vice head of a ‘partitionist’ government, he hit out at those ‘Dissident’ Republicans who tried to resurrect the days of ‘armed struggle’. After the killing of two British soldiers and a PSNI policeman in 2009, McGuinness called the perpetrators ‘Traitors to Ireland’.[16]

McGuinness also had an unsuccessful tilt at becoming President of the Republic of Ireland in 2011.

In late 2016, McGuinness was diagnosed with a serious illness, amyloidosis. He resigned as Deputy First Minister, coincidentally during a corruption scandal that brought down the Executive in January 2017 and died on March 21st.

Legacy?

McGuinness maintained in a late interview that he did not care how historians viewed his legacy. And yet, even at this early stage, we must try. Gerry Adams has said that, ‘Martin McGuinness never went to war, the war came to him’.[17] Certainly there is some truth to this; it was circumstances, the outbreak of violence in Derry and the North generally in 1968-69, not abstract nationalism, that drove McGuinness into the IRA.

McGuinness would come to paint his paramilitary career as defensive, ‘the only option’ under the circumstances. We should not accept this too uncritically. Many others in the Bogside, who experienced exactly the same set of circumstances, never agreed with the use of violence and it is significant that Martin McGuinness was not elected as a Member of Parliament for Mid Ulster until 1997, despite over a decade of trying.

McGuiness was one of a generation of IRA leaders who chose to prolong the guerrilla campaign for nearly three decades in pursuit of their political goals. That he finally helped to bring the violence to an end is certainly to his credit. However, contrary to those who would like to paint this as a conversion to pacifism, or on the other hand, those who see his late career as treachery, compromise was probably chosen on practical and tactical grounds as much as on moral ones.

If he was drawn into the conflict by the circumstances of his own nationalist, Catholic community in Derry, then he was also motivated in the end, by the advancement of that community through power sharing rather than the purist pursuit of Republican goals.

Today, in the wake of the United Kingdom’s exit from the European Union, mainstream voices are again beginning to speak seriously about united Ireland. In the North, nationalist votes are just a knife edge away from outnumbering unionists. All of which may appear to vindicate McGuinness’s tactical choices of later life.

There are those who cannot forgive him, even in death, for on the one hand, the pitiless infliction of grief on the unionist community and on the other for the ‘sell out’ of the IRA armed struggle. History, in the end, is likely to be kinder.

See also, Interview with Brian Hanley on Martin McGuinness

References

[1] Patrick Bishop, Eamon Mallie, The Provisional IRA, (1987) p. 319

[2] Ed Moloney, Secret History of the IRA (2002) p. 357-360. The date of October 1970 is from Bishop, Mallie, Provisional IRA p. 155

[3] http://www.irishtimes.com/news/politics/from-the-archives-martin-mcguinness-profile-of-a-provo-1.3020535

[4] Patrick Bishop, Eamon Mallie, The Provisional IRA, P144, 156

[5] See CAIN chronology, http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/sutton/chron/1971.html

[6] Many accounts from those on the ground in Derry cite McGuinness as being command of the Provisional IRA there at that time. Bishop and Mallie in the Provisional IRA say that he was given command of the Derry Brigade by Sean MacStiofain, the P.IRA’s Chief of Staff in the aftermath of internment in 1971 (p. 187). Eamon McCann, a prominent Derry activist at the time, named McGuinness as ‘the Provisionals’ OC’ in War and an Irish Town, p157. McGuinness himself testified at the Saville Inquiry in 2002-2003 that he was Second in Command of the Derry Brigade at the time and the Report concluded that he was the Brigade’s Adjutant. See http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/events/saville_inquiry_into_bloody_sunday for a summary.

[7] Bishop, Mallie, Provisional IRA, p. 187

[8] Eamon McCann, War and an Irish Town, p162.For the, unproven, Claudy allegations see http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2017/03/21/martin-mcguinness-took-ira-victims-secrets-grave-say-families/

[9] Bishop, Mallie, p. 226-228

[10] Peter Taylor, Provos, the IRA and Sinn Fein, p151-152

[11] For the effects of the ceasefire see, Ed Moloney the Secret History of the IRA, p. 143-147. The loyalist groups murdered 250 Catholics civilians in this period and the IRA or other Republican groups in response murdered 150 innocent Protestants.

[12] Bishop, Mallie, Provisional IRA, pp. 311, 315, 319

[13] Brendan O’Brien, The Long War, p 152.

[14] Moloney, Secret History of the IRA, p. 371

[15] http://archive.niassembly.gov.uk/record/reports/980701b.htm

[16] http://www.irishtimes.com/news/dissidents-behind-attacks-are-traitors-says-mcguinness-1.837329

[17] http://www.thejournal.ie/martin-mcguinness-gerry-adams-3298380-Mar2017/