‘Preserving the spirit of the movement’: The IRA, the Broadway Cinema and the 1943 Easter Rising commemoration

By Alison Martin

In comparison to some of the Easter Rising commemorations which took place around the time of key anniversaries, there has been relatively little focus on the 1943 commemoration which took place at the Broadway Cinema on the Falls Road.

This incident which involved around sixteen IRA men taking hold of the cinema, has mainly been referred to in the context of the lives of IRA men Jimmy Steele and Hugh McAteer. At the time however, this particular commemoration attracted a reasonable amount of publicity and was even referred to in newspapers as far away as Melbourne.

Sixteen wanted IRA men took over the Broadway cinema in Belfast and read out the 1916 proclamation.

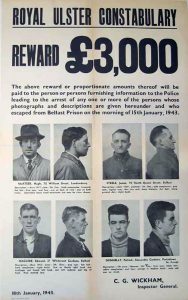

The 1943 commemoration was held against the backdrop of a number of publicity coups for the IRA. In January of that year Hugh McAteer, the IRA Chief of Staff and his second in command Jimmy Steele, escaped from Crumlin Road Jail along with two colleagues. Following his re-arrest, McAteer and twenty other IRA men gained considerable newspaper coverage by staging a dramatic escape from a Derry prison. Within hours, many of those who had escaped surrendered and ended up being re-interned. Nevertheless, this high-profile stunt served as a publicity boast for the organization.

Although by no means inactive during the early 1940s, the northern IRA were facing a number of setbacks. By 1942, more than 400 IRA suspects were interned in the north.[1] In August of the same year, the police discovered a large arms dump on a farm outside Belfast. It was therefore evident that a change of tactics were necessary.

In a Sunday Independent interview in 1951, McAteer claimed that by April 1943 the IRA leadership were openly admitting to each other that the military offensive which had begun in the north in 1942 was failing.[2]

Their main objectives were therefore ‘to ‘preserve the spirit of the movement’ and to keep its members out of prison ‘for as long as possible.’[3] It was against this backdrop that the Broadway Cinema commemoration took place.

The idea of staging a commemoration at the cinema had originated from a throwaway suggestion by two young IRA volunteers. Before long, the idea had expanded to a full dress commemoration. The cinema also had symbolic significance as it was built on the site of the Willowbank huts where the Irish Volunteers had been drilled. There was a also a more practical reason for the choice of location.

Harry White, the OC of the IRA’s Northern Command, had been staying at the house of Willie Mohan, a projectionist in the cinema whose bother was an internee. Mohan’s uncle was also the manager. Therefore it was known that the projectionist would usually go for a smoke between films, leaving the door unlocked. This would provide the IRA with a short window of opportunity to gain access to the equipment.

In Northern Ireland an outright ban had been placed on Easter commemorations from 1936 onwards

On Easter Saturday the 24th April, several IRA members converged on a house near to the Broadway Cinema, before proceeding towards the location in pairs. There was a strong police presence in the area as in Northern Ireland an outright ban had been placed on Easter commemorations from 1936 onwards.[4] In spite of the high security, they managed to make it to the cinema without incident. Eventually, around fourteen armed IRA men took up positions around the building, while McAteer and Steele took their seats in the audience.

The film being shown was Don Mosco, an Italian film focusing of the life of the famous Catholic priest (1935). Given the location of the cinema and the subject of the film it was hoped that the audience’s reaction would not be too hostile. Much to the surprise of the audience when the film ended and they tried to move towards the exit they were instructed to return to their seats as McAteer and Steele took to the stage. The manager and projectionist were held up. Then a slide was flashed across the screen stating:

‘This cinema has been commandeered by the Irish Republican Army for the purpose of holding the Easter Commemoration for the dead who died for Ireland.’[5]

The 1916 Proclamation was read aloud by Steele. He was closely followed by McAteer, who read an IRA Army Council statement which had been issued several months earlier. When the statement was over, two minutes silence was held for those who had died for Ireland. For McAteer, there were clear parallels between this public reading of the proclamation during a time of war and the original reading of the proclamation in Dublin in 1916.

This publicity coup was short-lived. In May 1943, Steele was recaptured in Belfast and McAteer was to follow a few months later

The army council statement focused on the presence of American soldiers who had arrived in Belfast during the previous year. The council emphasized that Britain did not have the power to ‘maintain forces in Irish territory without the free consent of the Irish people.’[6] Interestingly during the previous year, De Valera had also issued a statement in which he objected to the landing of American troops in Northern Ireland. He complained that the Irish government had not been consulted by either Britain or America.

The council however, did more than just protest claiming that the IRA had the right ‘to ‘use whatever measures present themselves’ to clear Irish territory of these forces.[7]

The public were also urged to oppose conscription. When the commemoration came to an end, the IRA left the building. According to the Ulster Herald ‘No one saw them come and no one saw the go.’[8]

The Broadway Cinema commemoration received almost unprecedented media coverage. Interestingly, the Irish Times reported that no commemoration had been held in Belfast. However, the Irish News reported enthusiastically on proceedings which were recounted in newspapers across the world. The Argus, a daily newspaper in Melbourne printed a short article about the incident on 27 April 1943. The incident was even reported on German radio, much to the annoyance of Unionists.

In a similar vein to the high profile prison escapes that had occurred earlier in the year, the 1943 commemoration acted as both a publicity and morale boost for the northern IRA. This occurred at time when the leadership were openly admitting to each other that the military offensive which had begun in the north in 1942 was failing.

This publicity coup however, was short-lived. In May 1943, Steele was recaptured in Belfast and McAteer was to follow a few months later. Any encouragement to be gained from the prospect of a British defeat in the war also evaporated as the tide began to turn in favour of the Allies. By December 1944, the Northern government felt confident enough to stand down the Ulster Home Guard, reducing the B Specials to their pre-war strength.

References

[1] Michael Farrell, Northern Ireland: The Orange State, p. 167.

[2] Sunday Independent, 20 May 1951.

[3] Ibid.

[4] This was renewed annually until 1949.

[5] Cited in Tim Pat Coogan, The IRA, p.186.

[6] The Mercury, 3 Sep 1942

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ulster Herald, 1 May 1943.