Today in Irish History, 28 June 1922, the First Day of the Irish Civil War

John Dorney on the first day of the Irish Civil War, an adapted extract from his forthcoming book, The Civil War in Dublin

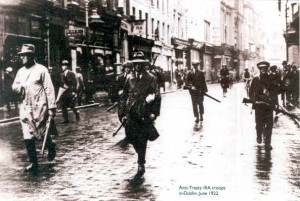

Late on the night of June 27, 1922, National Army or Free State troops in Dublin received orders to surround and if necessary attack the Four Courts in centre of the city.

The Four Courts, centre of the Irish judicial system, was the headquarters of the anti-Treaty IRA in Dublin, led by Rory O’Connor. It had been occupied the previous April, in defiance of the Provisional Irish Government set up under the Anglo Irish Treaty.

For nearly three months in Dublin and around the country there had been an uneasy co-existence between two rival Irish armed forces; one the National Army of the Provisional Government, the other, the anti-Treaty IRA, who in a Convention in March had repudiated the authority of the Dail and Provisional Government. The Four Courts faction was the most militant of all, just days previously they had announced their intention to declare war on Britain. [1]

On June 28 1922, pro-Treaty troops opened fire on the anti-Treaty garrison in the Four Courts, making the start of the Irish Civil War.

Now, the uneasy stand-off was coming to an end. Pro-Treaty troops were loaned two eighteen pounder field guns by the British and tonnes of other weaponry to bombard the Four Courts into surrender.[2] Inside the Courts, the 180-man garrison, unwilling to be the ones who fired first, watched as around 1,000 National Army troops surrounded their position, setting up a machine gun in the tower of St Michan’s Church which overlooked the complex and even blocking its gate with an armoured car. [3]

Tom Ennis, the pro-Treaty commander issued the Four Courts with the following ultimatum at 3:40 am:

‘I acting under orders of the Government hereby order you to evacuate the buildings of the Four Courts and to parade your men under arrest without arms on the portion of the Quays immediately in front of the Four Courts by 4 am. Failing compliance with this order the building will be taken by me, by force. You will be held responsible for any life lost and damage done’.[4]

There was next to no chance that the order, giving the Four Courts garrison only 20 minutes to surrender completely and face arrest, would be obeyed. According to Rory O’Connor, ‘I received a note from Tom Ennis at 3:40 am demanding surrender by 4 am. He then opened attack at 4:07 am in the name of the government with rifles, machine guns and field pieces.’[5]

The first shots from the 18-pounder boomed out across the river Liffey, followed by the crack of small arms fire. The Irish Civil War, the fratricidal conflict between former comrades had begun.

How had it come to this?

Three armies in Dublin

Both factions had been united in the IRA and Sinn Fein up until the publication of the Anglo-Irish Treaty on December 6, 1922. They had split acrimoniously in early 1922 after the Dail approved the Treaty but Eamon de Valera, the anti-Treatyites’ political leader, refused to accept its decision.

The division deepened in March 1922 when the IRA formally split, when the anti-Treatyites, in a convention at Dublin’s Mansion House, elected their own Army Executive and disavowed the authority of both IRA GHQ and the Dail or Irish Parliament as long as both accepted the Treaty. Still, Civil War itself took another three months to gestate.

Why did matters come to a head in late June 1922?

The pro-Treaty case was that they, in the Provisional Government set up in early 1922 to oversee the creation of the Irish Free State, could no longer tolerate what they described as ‘grave acts against persons and property have been committed in Dublin by persons pretending to act without authority… ‘Outrages against the nation must cease once and forever’.[6]. They had, they argued, won an election just ten days earlier on June 16 and had to assert their authority as the legitimate, elected Irish government against those illegally occupying the Four Courts.

The pro-Treaty Provisional Government argued that it was merely defending the will of the people and the rule of law by tackling the ‘Irregular’ garrison in the Four Courts

This was not without some justification. The Four Courts garrison had indeed been seizing property across the city, both buildings supplies and in some cases money, without any regard for the laws of the new state, since early April. Todd Andrews, one of the Four Courts men, recalled that they had ‘forcibly requisitioned’ £50,000 from the Bank of Ireland as well as meat and vegetables from the local shops. [7]

On 26 of June, a raiding party from the Four Courts led by Leo Henderson arrived Ferguson’s Garage on Baggot Street, a well-known Belfast firm, and seized four cars, in punishment for their doing business with the northern city, at a time when violence was raging there against the nationalist minority. This time though, the pro-Treaty government took action. Leo Henderson, who led the raid was arrested by pro-Treaty troops under Frank Thornton.[8]

In the Four Courts, the anti-Treaty leadership, according to Ernie O’Malley in response to the arrest of Henderson, considered abducting Michael Collins or Richard Mulcahy before settling on National Army General JJ ‘Ginger’ O’Connell. They seized him at gunpoint as he came out of McGilligan’s pub and held him as a hostage in the Four Courts to be released in exchange for Leo Henderson. O’Malley personally telephoned pro-Treaty General Eoin O’Duffy in Portobello Barracks to give him the message. [9]

In a narrow sense, the rival arrests of Henderson and O’Connell led to the attack on the Four Courts and the beginning of the Civil War. The Provisional Government stated that they had, ‘been compelled to take action after a series of criminal acts culminating in the kidnapping of General O’Connell’.[10]

But this is to ignore the role of the most powerful military force in Dublin at the time; the British Army, commanded by Neville Macready, a 6,000 strong force based in the barracks at the Phoenix Park and three others around the city.

In fact, it was the threat that the British garrison would attack the Four Courts that forced the Provisional Government’s hand.

On June 22, 1922, Field Marshal Sir Henry Wilson was gunned down in London by two IRA members, Reggie Dunne and Joe O’Sullivan. It has never been proved who, if anyone, gave them the order to do it. Speculation abounds that Michael Collins himself may have ordered it in reprisal for Wilson’s role as military advisor to Northern Ireland, at a time when hundreds of Catholics and nationalist were being killed there, and certainly Collins seems to have ordered that the rescue of the two gunmen be investigated. [11]

Correspondence between the British Government and the Irish Provisional Government shows that Michael Collins wished to resolve the Four Courts Stand-ff peacefully. It was British pressure that forced his hand.

The British government, though, assumed that the Four Courts garrison was responsible and Lloyd George, the Prime Minister, sent an ominous letter to Michael Collins. He wrote that Wilson’s assassins had been identified as IRA members and their papers ‘reveal the existence of wider conspiracy against law and order in this country’. It warned that,

‘The ambiguous position of the Irish Republican Army can no longer be tolerated by the British government. Still less can Rory O’Connor be permitted to remain with his followers and his arsenal in the heart of Dublin in possession of the Courts of Justice organising and sending out from this centre enterprises of murder in your jurisdiction, the six counties [Northern Ireland] and Great Britain’.

It ended with a straightforward demand for the Provisional Government to attack the Four Courts.

The British government feels entitled to formally ask you to bring it to an end forthwith. We are prepared to place at your disposal the necessary pieces of artillery…or otherwise to assist you as may be arranged. [12]

Diarmuid O’Hegarty wrote back carefully on Collins behalf, maintaining, ‘The Government is concentrated on the Four Courts situation [but is] ‘satisfied that these forces contained within themselves elements which would cause disintegration and relieve the Government of the necessity of employing methods of suppression’. [13]

O’Hegarty said the Provisional Government intended to call the Dail, elected in June 1922, on July 1, before they took any further action. But the Irish parliament was never consulted on the decision to attack the Four Courts. The Third Dail did not meet until September 1922, well into the Civil War.

In light of O’Hegarty’s non-committal reply, the British cabinet ordered General Macready to launch an assault on the Four Courts with artillery, tanks and aerial bombing. Only at the last minute did Macready, on his return to Dublin from England, persuade his superiors to give the Irish Provisional Government a final opportunity to take the Four Courts themselves. [14]

Michael Collins, Arthur Griffith and their colleagues now had no further options. It was at this point that Leo Henderson was arrested seizing cars bound for Belfast and the Four Courts garrison snatched Ginger O’Connell in response, giving the pro-Treaty authorities their official casus belli.

The Four Courts anti-Treaty IRA garrison were certainly wilfully defying the laws of the nascent Irish government and threatening to provoke a new war with the British. In the days leading up to the attack on the Four Courts they had even fallen out with anti-Treaty IRA Chief of Staff Liam Lynch over their unilateral declaration of war on the British. To some extent, a conflict between them and the Provisional Government was inevitable.

Anti-Treaty Republicans saw the attack on the Four Courts as unprovoked aggression on behalf of the British by the Provisional Government. It was this perception that caused all out Civil War.

But it is clear had matters been left to Collins and his colleagues, they would still have attempted to find a peaceful solution or as O’Hegarty put it to the British, have allowed the Four Courts faction to fall apart due to their own internal disagreements.

That the pro-Treaty troops attacked the Four Courts on British orders meant that, to anti-Treaty Republican minds at any rate, this conflict was a defence of the Irish Republic against British-backed aggression.

Eamon de Valera on June 28 issued a statement that;

‘At the last meeting of the Dail we had an agreement to work for internal peace [but now] at the bidding of the English it is broken and Irishmen are shooting down brother Irishmen in the face of English threat’.[15]

The defence of Irish democracy against anti-Treaty militarism or the defence of the Irish Republic against British attack? These two discordant views could not be reconciled after the attack on the Four Courts began.

Choosing sides

The majority of combatants on both sides of the Four Courts siege had served in the pre-Truce IRA. The high politics of the Civil War divide generally meant less to them than personal loyalties.

Michael Collins’ dedicated followers in the IRA Squad, Intelligence Department and Dublin Active Service Unit were pro-Treaty, mainly out of their loyalty to him. Most of the rest of the IRA Dublin Brigade was anti-Treaty however.

Nevertheless many men agonised over which side to take once firing had broken out.

Joseph Lawless, for example an IRA man from North County Dublin had joined the pro-Treaty Army at Beggar’s Bush Barracks back in February 1922, but, disillusioned by the split, had since dropped out of it since. Nevertheless, ‘we deluded ourselves that it would never go to the length of actual civil war’. At first he thought, ‘I could not take active part on either side’. But finally after talking with some pro-Treaty friends he decided to re-join the National Army in Portobello Barracks, ‘to offer my services in any capacity’.[16]

Combatants generally chose sides based on personal loyalties as much as ideology.

On the other side Joseph Clarke, another IRA veteran, had joined the Free State Detective unit the CID ‘7 or 8 weeks before attack on Four Courts’. But on the morning of the attack on the Courts he, ‘Met with an old 1916 man [i.e. a veteran of the Easter Rising of 1916] that morning who told me British soldiers were firing on the Four Courts’. He ‘went to Parnell Square got in touch with Paddy Houlihan’ and subsequently took part in fighting on the anti-Treaty side.[17]

Republican women, too, were split. The majority of the women’s group Cumann na mBan had voted to reject the Treaty back in February 1922. Now, the anti-Treaty women were to the forefront in the fighting. Maire Comerford commandeered a lorry and drove it into the Four Courts, Constance Markievizc sniped at pro-Treaty troops on O’Connell Street . On the other side though, Cumann na Saoirse, a pro-Treaty women’s group led by Jenny Wyse Power, who had split from Cumann na mBan when the latter rejected the Treaty, organised food and medical care for National Army troops. [18]

Fighting

Initially the fighting at the Four Courts did not go well for Provisional Government Forces. They had hoped that a show of force and especially the deployment of artillery would intimidate the anti-Treaty garrison into a quick surrender. This did not happen.

The anti-Treatyites in the Four Courts, though in an impossible military position, were determined to resist and the supply of shells the British had given to the National Army troops was not enough to cause real damage to the structure. It was not until the following day that the British donated two more field pieces and hundreds more high explosive shells.

By the end of June 28, little progress had been made by pro-Treaty troops in taking the Courts.

On the first day of fighting, pro-Treaty troops made little progress at the Four Courts and fighting spread to the rest of Dublin.

There were casualties inside the Four Courts, three wounded by gunfire and another killed outside on Ormonde Quay[19], but the pro-Treaty soldiers outside suffered more. At least two of them were killed around the Four Courts on June 28 and many more wounded [20]. Fourteen year old Patrick Cosgrave, a messenger boy was one of the first civilian casualties. He was shot dead at George’s Hill, just behind the Four Courts; one of at least 8 civilians killed in the crossfire in Dublin that day. [21]

Elsewhere in the city, National Army troops under Frank Bolster had also been sent to attack other anti-Treaty outposts, particularly the Orange Order Hall on Parnell Square, that the anti-Treaty Republicans had occupied back in April. There was some sharp fighting in which a National Army sergeant was mortally wounded and an anti-Treaty IRA Volunteer killed by a sniper. Two civilians also lost their lives.[22]

Bolster’s troops used a Rolls Royce armoured car, with its Vickers belt-fed machine gun, to pepper Fowler’s Hall while also bombarding it with rifle grenades. After several hours the building caught fire and had to be evacuated, but the anti-Treaty fighters did not go far, retreating to the adjacent North Great George’s Street and the top of O’Connell Street where Oscar Traynor, leader of the anti-Treaty IRA Dublin Brigade set up his command post in Barry’s hotel. [23]

When the fighting broke out, anti-Treaty elements of the Dublin Brigade occupied further positions across the city, notably on the eastern side of O’Connell Street, and on the southside, York Street and the Malt Factory in Newmarket in the Liberties. There were also skirmishes in Dun Laoghaire, Clondalkin and Dolphin’s Barn. [24]

By the end of June 28, 1922, fighting was raging across Dublin city centre. The press reported that 15 people had lost their lives so far and another 40 had been wounded. [25]

Many neutrals were dismayed by the outbreak of fighting. The Labour Party issued a statement denouncing the outbreak of hostilities; ‘Suddenly without warning, two armies whose leaders had been in friendly conference, whose officers had been fraternising, found themselves at war’. [26]

Labour leaders Cathal O’Shannon, Duffy and Thomas Johnson, wrote to Lord Mayor of Dublin, Laurence O’Neill, regarding the ‘hostilities now going on in the city’ and made a ‘strong protest on behalf of the civilian population’ … [We are] ‘against the Government action in attacking the Four Courts without prior explanation to the public regarding the sudden change in policy towards the Executive [anti-Treaty] forces’. Together, they sent a delegation to the government asking for a ceasefire.

Though the pro-Treaty authorities won the ensuing battle, the cost was the outbreak of Civil War around the country.

Arthur Griffith rebuffed the delegation and told them, ‘We are a government and we are going to govern. We will not be drawn into the Red Herring of the civilian population’. [27]

Although the Four Courts would surrender within three days and the rest of the anti-Treatyites would be ousted from their positions in Dublin within a week, the attack on the Four Courts was not a quick, clean victory for the Provisional Government as they had hoped, against an isolated extremist faction.

Rather, because of the Republican perception (justified or not) that that Four Courts had been attacked without provocation on British orders, it would instead spark off a prolonged and tragic period of Civil War.

References

[1] Sean MacBride notes on June 18 convention, cited in, Comrac O’Malley, Anne Dolan, No Surrender Here, The Civil War Papers of Ernie O’Malley, p26-27.

[2] Frank Carney Chief of Supplies officer Portobello Barracks said in 1924 that on the eve of the attack on the Four Courts, ‘the Free State ordered from the British 3 million rounds of .303 [rifle ammunition], 50,000 rounds .45 [pistol ammunition], 7 armoured cars, 2 field guns, 200 shells, 1,000 incendiary bombs, 10,000 grenades’. De Valera Papers UCD P150 /1627

[3] Diarmuid O’Connor, Sean Connolly, Sleep Soldier Sleep, The Life and Times of Padraig O’Connor, p.91

[4] De Valera Papers UCD P150/1627

[5] Ibid.

[6] Statement 28 June 1922, Mulcahy Papers P7/B/192

[7] CS Andrews, Dublin Made Me, p. 236.

[8] Mulcahy Papers UCD P/7/B/192

[9] O’Malley, The Singing Flame p 88

[10] Mulcahy papers UCD P7/B/244 Cabinet Minutes 27 June 1922

[11] According to Joe Dolan, by that time in Military Intelligence in Oriel House, Collins ordered him to go to London to meet Sam Maguire, the IRB centre there to look into a rescue effort. Dolan reported that snatching them on their way to court was feasible if he had 6 Squad or ASU men. But by the time he got back to Dublin the Four Courts had been attacked and the Civil War was on. BMH WS 900 On the other hand, George White an anti-Treaty Volunteer also met with the London IRA OC, Kelleher, about the possibility of rescuing Dunne and Sullivan, and even Liam Lynch was approached, who said he would do what he could. According to White Kelleher also spoke with Collins in Portobello Barracks but was afterward put under arrest. So it looks as if the London IRA appealed to both pro and anti-Treaty IRA factions to attempt to rescue the men. George White BMH WS 956

[12] Lloyd George to Collins 22 June 1922, Mulcahy Papers UCD P7/B/244

[13] O’Hegarty to Lloyd George, De Valera Papers UCD P150/1625

[14] Michael Hopkinson Green Against Green, the Irish Civil War, p116-117

[15] De Valera Papers UCD P150 /1588

[16] Joseph Lawless BMH 1043

[17] Joseph Clarke Pension Application 1924A9

[18] Máire Comerford Papers UCD LA/18/43. Sean Boyne, Emmet Dalton, p. 148.

[19] He was Volunteer William Doyle, originally of New Ross Co Wexford, The Last Post (1985)

[20] They were Privates George Walsh and Patrick McGarry, Pension applications here and here. A Commandant T Mandeville of the Beggars Bush GHQ Staff and Ca[tain Michael Vaughan were also killed on June 28 on Leeson Street.

[21] Irish Times July 4, 1922, also information from Lynn Brady, genealogist of Glasnevin Cemetery

[22] He was William Brennan a former British Army soldier who shot in the abdomen around O’Connell Street. He died on July 4th, pension application here. The dead IRA Volunteer was William Clarke of Corporation Street, Dublin. The Last Post (1985) p.

[23] Liz Gillis the Fall of Dublin p56-59

[24] Mulcahy papers UCD P7/B/40 NA reports Report from NA AG 28/6/22. The IRA man killed in Clondalkin was John Monks of Inchicore, killed on June 29th. The Last Post 1985. The civilian killed in Dun Laoghaire on June 29th was John McCormack a labourer who was shot in the chest, reported in the Irish Times, July 4, 1922.

[25] Irish Times, July 7 1922

[26] August 1922 Labour Conference De Valera Papers UCD P150/1607

[27] Ibid.