Book Review: Monteith: The Making of a Rebel

By Catherine C. Smyth (2017)

Reviewer: Daniel Murray

Roger Casement was a sick man. Amidst all the uncertainties facing the tiny band of Irish revolutionaries on board the cramped German U-boat, that much was all too clear.

Fearful that his companion might collapse under the twin strains of ill health and worry, Robert Monteith suggested that he catch some sleep. Casement tried to but, after half an hour, he was back to fretting.

At the mouth of the Shannon, they had looked out from the conning tower, straining their eyes in the gloom for signs of the Aud, the ship due to deliver the much-needed weapons for the planned uprising. Despite an earlier sighting of the Aud – or what they thought it was – they found nothing. After cruising for an hour and a half, the captain announced they could wait no longer, and directed his submarine towards Tralee Bay.

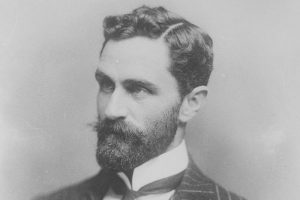

Robert Monteith accompanied Roger Casement on his fateful journey back to Ireland in 1916.

Before disembarking on the Kerry coast, Monteith took out their firearms and asked his companion: “Do you understand the loading of these Mauser pistols?”

“No, I have never loaded one,” Casement replied. “I have never killed anything in my life.”

“Well, Sir Roger, you may have to start very soon,” Monteith said. “It is quite possible that we may either kill or be killed.”

Monteith tried to teach Casement the basics of handling their pistols, but the other man decided that such skills were not for him and handed the weapons back with a shake of his head.

At least Casement had retained some sense of the occasion. As Monteith bemoaned the incongruity of trying to liberate their country under such woebegotten circumstances, Casement hushed him.

“It will be a much greater adventure going ashore in this cockle shell,” he said, in reference to the small boat they were lowering themselves into.

For Monteith, it was but the latest adventure in what had already been an eventful life. Born in 1878 in Co. Wicklow, he had enrolled in the British Army and was posted to India, during which he was shot in the mouth, dislocated his hip when a horse threw him, and learned to speak a local dialect. Later he volunteered to serve in South Africa, where the ‘scorched earth’ policy he helped inflict during the Boer War gave him a different perspective on the cause he was serving:

Monteith volunteered to serve in South Africa, where the ‘scorched earth’ policy he helped inflict during the Boer War turned him against British imperialism.

In the smoke and red flames of the first Boar [sic] farmhouse I saw burned, there appeared to me the grisly head and naked ribs of the imperialist monster. I realised why the women and children knelt in the shower of sparks to curse us.

Still, in a way, Monteith thought the Indians and the Boers had it easy compared to the people of his own homeland:

I have been in the villages of Bengal and the Punjab in India, and in the kraals of the so-called savages of Africa, with whom it is a crime to beat a child; I have eaten with the Zulu, Basuto, Swazi and the Matabele, and can say without fear of contradiction that the conditions under which these ‘benighted heathens’ live are far above those of the Christian workers of Dublin.

Perhaps it is unsurprising that after all this, not to mention a bout of malaria, a photograph of a uniformed Monteith, as he neared his Army discharge after eight years of service, shows a thin, serious-looking man, still only twenty-five.

Back in Ireland, where he owned a small Dublin-based printing press, Monteith’s feelings of discontent crystallised into open outrage upon seeing the beating to death of a man by police (and his own battering when he intervened) during the Dublin Lock-out of 1913, as well as the clubbing of his stepdaughter.

Monteith decided to enlist in the Irish Citizen Army but was persuaded by Tom Clarke, an acquaintance of his, to instead channel his military know-how into the nascent Irish Volunteers. Sworn into the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) by Clarke, Monteith was sufficiently trusted to be offered the chance to assist Casement in Germany, where he was attempting to form an ‘Irish Brigade’ from the inmates of POW camps there.

In 1913, Monteith was recruited by the IRB and sent to Germany to help Roger Casement recruit an ‘Irish Brigade from among Irish prisoners of war.

Monteith agreed and met Casement in Munich, October 1915. Casement made an instant impression on Monteith, who was to wax lyrically about his new colleague: “I have known no eyes more beautiful than Casement’s…Blazing when he spoke of man’s inhumanity to man; soft and wistful when pleading the cause so dear to his heart; mournful when telling the story of Ireland’s century old martyrdom.”

Casement’s story was almost as much Monteith’s as well, so entwined were their lives at this point. Not for nothing was Monteith’s memoir – quoted liberally by Smyth in her book – entitled Casement’s Last Adventure.

The reality of the situation, however, proved to be…challenging. Even then, Casement was visibly ill and nervous. As for the Irish POWs, they were not always a receptive audience. A not-untypical entry in Monteith’s diary read:

3 November 1915: Commenced recruiting campaign at 9 a.m. and continue till noon. Started at 2 p.m. and worked till 5 p.m. These hours were chosen so as not to interfere with meal hours of men. Men seem indifferent. A lot of them are absolutely impossible.

Much to Montheith’s bewilderment, the prisoners seemed too content with their situation for anything as bothersome as reenlistment. “All of them are loud in their statement that when the war is over they will be prepared to fight for Ireland. God help us!” Monteith wrote, and more in a similar vein.

At least a proposal by the IRB Military Council to have a boat loaded with armaments sent to Ireland gave Casement a new lease of life. As Monteith remembered: “He was so happy at the news I brought, that he immediately slipped out of bed, and started to work on plans or suggestions, to help the German General Staff and Admiralty, on the work in hand.”

As it turned out, neither the German Command nor the IRB had much further use or interest in him. When Casement, realising this harsh truth, insisted on going on board the same ship, Monteith tried vainly to talk him out of it. Their German point-men, in contrast, made no such effort. At least Casement and Monteith still had each other, the latter loyally refusing to allow the other to risk himself alone.

Smyth’s book reads like a novel, fast-paced and by turns exciting and depressing. Poor Casement! Monteith at least managed to avoid capture in Kerry. He left Casement, too sickly to carry on, in an ancient ring-fort that would provide some shelter. By the time Monteith reached Tralee and alerted the local Irish Volunteers, Casement had already been found and arrested by a police patrol.

Smyth’s book reads like a novel, fast-paced and by turns exciting and depressing.

Hiding out in Tralee, Monteith could still hope that the Aud would finally arrive with its catchment, but even that was not to be. With orders, countermanding orders and general confusion marking the Rising-that-was-not-to-be in Kerry, Monteith wisely turned down the offer to command the Irish Volunteers gathering in Tralee.

Instead, he went on the run, managing to stay one step ahead of his police pursuers, and eventually made it to the safety of New York. He was by then suffering from nervous exhaustion, something which the readers will relate to by the time they come to the end of this gripping book.

While awaiting the hangman’s noose, an imprisoned Casement wrote to his sister to say: “The only person alive, if he is alive, who knows the whole of my coming and why I came, with what aim and hope, is Monteith. I hope he is still alive and you may see him and he will tell you everything.”

Monteith told a lot more people via his memoirs, and it is fitting that the same tragi-comic story should continue to be told here. What a tale! And what an adventure, as Casement observed, albeit not a very happy one, as he and Monteith would also have agreed with.