Catalonia and Ireland

In the aftermath of the putative independence referendum in Catalonia, on October 1, 2017, John Dorney looks at some of the parallels between that region’s (or is it a nation?)’s history and that of Ireland.

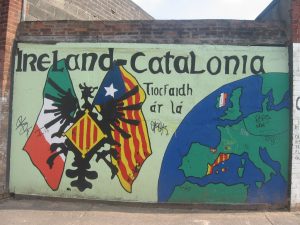

Ireland’s struggle for independence was, and to a degree is, keenly observed by other small nationalities with ambitions for statehood.

In late 1920, at the time when the War of Independence was raging in Ireland, nationalist activist Maire Ni Bhrian arrived in Barcelona as part of a Europe-wide tour to publicise the cause of Irish independence. It was shortly after the death of Terence MacSwiney the Lord Mayor of Cork, who had died on hunger strike in London, in protest at this arrest by British forces.

Ni Bhrian recalled,

‘In Barcelona and in Catalonia generally there was the deepest sympathy for Ireland and when Terence died the papers there were full of articles about him and masses were offered for him in many churches which were crowded to the door… The university students and shop assistants all wore green buttons. There was a huge meeting in the beautiful club hall of the shop assistants with the [Irish] tricolour at the end of the hall facing the platform… The Catalans always cherish the desire for separation from Spain and their aspiration for independence is the bond between them and us.’

‘All the speeches made that evening, she remembered, though they had to be translated from Catalan into French for her, ‘were in praise of Ireland and expressed sympathy for our objects in our fight for freedom’.[1]

On the whole however, such admiration as has existed has largely been one sided. Whereas Irish Republicans have had long-standing links to Basque nationalists further west along the Pyrenees (as explored in this 2010 Irish Story article), there have never been such close ties between Irish and Catalan separatists.

While IRA leader Ernie O’Malley met some Catalan nationalists in 1924-25 and while Sinn Fein’s Eoin O Broin was invited to observe the 2017 referendum, such explicit contacts have been few and far between.

Divergent histories

If one accepts the nationalist narrative of both Ireland and Catalonia, they are both (or have both been) oppressed small nations, each with its own distinctive language and culture, ever seeking to break away from, respectively, Britain and Spain.

In some respects Catalonia’s history has more in common with Scotland than Ireland.

However, in truth, the Irish case and that of Catalonia differ in many ways. To start with, Catalonia’s incorporation into the Spanish monarchy in 1492 was not as a result of conquest, but as a result of the union of the Crowns of Castille and Aragon. In this respect, it has more in common with Scotland, joined to England in the person of the Scottish King James I in 1603, than Ireland, which was effectively conquered by English monarchs who proclaimed themselves Kings of Ireland.

Moreover, whereas Ireland was colonised with Protestant, English speaking, settlers, nothing of the kind occurred in Catalonia. And while both countries have a ‘rebel’ tradition dating back, at least, to the 17th century, they are in some respects, quite different.

For instance, both Catalonia and Catholic Ireland rebelled against Madrid and London respectively in the 1640s. Both were part of a Europe wide series of civil wars and revolutions in the middle of the seventeenth century. In Ireland the rebellion was a bloody revolt against English and Protestant domination, sparking a short lived Catholic ‘Confederate’ government before its final defeat at the hands of Cromwell’s New Model Army in the 1650s.

In the case of Catalonia, revolt, known as the ‘Reapers’ War’ was caused by King Phillip IV’s extension of taxation and conscription, to fund his wars with France, to Catalonia, which had previously been exempt under the terms of its self-governing laws.

One royal report on Catalonia from 1640 has an oddly contemporary feel about it;

‘It contains a villainous populace, which can easily be excited to violence and the more it is pressed, the harder it resists… [so repression] only succeeds in exasperating the inhabitants of this province and in making them insist more stubbornly on the observance of their laws.’[2]

Like the Irish Catholics, the Catalans sought aid from outside powers, France in their case, and briefly declared a Catalan Republic before going down to defeat, also in the 1650s, when Spanish armies, including as it happens, Irish Catholic troops, were redeployed from northern Europe to crush them.

Whereas the causes of Ireland’s rebellion was largely religious and ethnic, in Catalonia, language and culture played a role, but the driving force was economic and defence of their existing governing institutions.

There are further parallels however. In the 1690s Irish Catholics took up arms in defence of the Catholic King of England James II and were defeated, in return being punished with the ‘Penal Laws’ designed to suppress Catholicism and dispossess Catholics in Ireland.

Similarly in the War of Spanish Succession (1702-1714) the Catalans fought for the last Habsburg claimant to the throne of Spain. He was defeated by the Bourbon King Phillip V, who, on conquering Barcelona after a siege in 1714, abolished Catalan and Aragonese autonomy and abolished the use of Catalan as an administrative language. It was a defeat Catalan nationalists still remember today, much as Irish nationalists once used to rue the surrender of the Jacobites at Limerick in 1691. [3]

In summary, while both Catalonia and Ireland could both recall bitterly the defeats of the 17th and 18th centuries, there were important differences. The religious and social chasm that existed in Ireland between conqueror and coloniser was not present in Catalonia. While Ireland was a poor adjunct to a much richer Kingdom in England, Catalonia was the opposite, from the start, a rich region that resented subsidising the government in Madrid.

Finally, while the Catalan language took a blow as a result of political and military defeats in the eighteenth century, it remained the dominant language, including of the upper classes, whereas the Irish language throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, with its native aristocracy banished, dispossessed or assimilated, became largely a peasant language.

National rebirths

All of this mattered a great deal when both countries began to develop modern political nationalism in the late 19th century.

Language and economics has always been at the core of Catalan nationalism, less so the tradition of armed rebellion so prevalent in Irish history.

Whereas Irish language and culture formed a central part of Irish nationalist discourse at the dawn of the twentieth century, most Irish nationalists and Republicans were English speakers who had to learn Irish as adults. What was more, over the second half of the nineteenth century, especially after the Great Famine, the Irish language retreated rapidly so that by1900 it had only footholds, mostly along the western coast.

Catalan nationalists by contrast not only spoke the language but could count, certainly on the more rural population, for whom it was also their first language, for support.

And again, whereas Irish nationalists certainly made economic arguments in favour of independence, it was never the core of their case, which was based more on a sense of Irish Catholic communal injustice as well as colonial-style rule by ‘Dublin Castle’.

In Catalonia, by contrast, while Catalan nationalists of the renaixenca (Catalan renaissance) certainly wrote poems about the beauty of their country and its language and fulminated against its suppression by ‘Madrid’, there was always a powerful economic element, a sense that wealthy Catalonia was being bled dry by a spendthrift Madrid.

Another striking distinction was that Catalonia became one of Spain’s industrial centres in the late 19th century (the other was the Basque Country). As a result many workers migrated there from the rest of Spain, so while the proletariat in early 20th century Catalonia was largely Spanish speaking, its bourgeoisie was Catalan – a situation that had no parallel in Ireland.

It has been suggested that the fact that Catalonia was in many ways a self-confident, powerful nationalism meant that it preferred gradual, reformist politics rather than cult of armed struggle and martyrdom that so marked Irish nationalist (and not only Irish) history.

Civil War

Catalonia had a rebel tradition in the early 20th century, but it was not nationalist. Barcelona in particular was known for its militant labour and anarchist politics.

In 1909, left wing workers rioted against the imposition of conscription for a war in Morocco, burning churches and sacking businesses, in what almost amounted to an insurrection. Hundreds died in the subsequent military repression that became known as ‘Tragic Week’. However this was an anarchist, anti-clerical affair, not an expression of Catalan nationalism. [4]

Today, many Catalan nationalists appear to wish to re-write the history of the Spanish Civil War of 1936-1939 as democratic Catalonia being attacked by a fascistic Spain. But this is a major over-simplification.

The Spanish Republic granted Catalonia autonomy for the first time in 1932 and certainly this was indeed abolished with the victory of the right wing authoritarian forces under Francisco Franco in 1939. Luis Companys, the wartime president of Catalonia and a Catalan nationalist, was executed by the Francoist forces.

In between however, it was the Spanish Republic, under government of the right party CEDA, that suppressed a self declared independent Catalan state (with some, though not great, violence) in 1934.

The actual Civil War of 1936-39,was far more a battle between right and left, including within Catalonia, than a struggle between Barcelona and Madrid.

When the right wing military uprising, aimed at toppling the Spanish Republic and the leftist Popular Front government, erupted in July 1936, it was not Catalan nationalists who defeated it in Barcelona, but armed workers, largely Spanish speaking and belonging to the anarchist CNT union or the Socialist and Communist parties. Thereafter, it was they, the left wing militias, who bore the brunt of the fighting and in the chaos of civil war, also turned their guns on each other at times.[5]

The Spanish Civil War was more a battle between left and right wing as between Madrid and Catalonia.

Some Irish Republicans fought in Catalonia in the Civil War but they did so as Republicans or socialists, not in solidarity with Catalan nationalists.

Moreover, while under Franco’s dictatorship (1939-1976), the Catalan language was banned and Catalan nationalists persecuted, Franco also had the tacit support of many Catalan industrialists, who were not displeased to see the militant workers’ movement broken.[6]

Whether for this or other reasons, there was no real Catalan equivalent of the Basque armed group ETA, which, from the 1950s until very recently used armed force against the Spanish state, both in its Francoist and democratic periods.

There was a short-lived Catalan militant group named Terra Lliure (Free Land) that operated in the 1980s and 1990s but it was responsible for only one death, as opposed to over 800 deaths that ETA is held to be responsible for. And both conflicts fall well under the figure of 3,500 people who died in Northern Ireland in the same period. So when militant Irish Republicans, especially from the 1970s onwards, looked for fellow thinkers within Spain, they naturally gravitated more to the Basques than to the Catalans.

Today

Since Catalonia was again granted autonomy after the return of democracy to Spain, and in particular after the passing of the constitution of 1978, it has been governed autonomously by its own government the Generalitat. Catalan has been made the compulsory first language in all state education and today is spoken by most residents of Catalonia.

Catalan nationalism therefore historically differs in many respects from its Irish counterpart. The principle difference being essentially that Catalonia is historically a rich and economically powerful region whereas Ireland, certainly under the Union with Britain was relatively poor and marginal.

This means that Catalan resentment at being ‘robbed’ by the rest of Spain has always and continues to be, a central part of Catalan nationalist thought that has no real equivalent in Ireland.

The refusal of the Madrid government to negotiate further autonomy has resulted in the Catalan nationalists’ calling a unilateral referendum, with dangerous consequences.

Secondly, while culturally, the cases appear to be similar, language is actually a far more important part of Catalan nationalism than Irish. Paradoxically this is probably because Catalan is far closer to Castilian Spanish than Irish is to English, meaning that it is relatively easy for a Spanish speaking migrant to learn. Thus many Catalans whose ancestors came from elsewhere are today Catalanistas themselves.

Thirdly, Catalan nationalism largely does not have the modern tradition of ‘armed struggle’ and ‘blood sacrifice’ that sustains militant Irish nationalism. Not up to now in any case.

The crisis of 2017 is largely the result of the refusal of the central government in Madrid to concede more autonomy to the Generalitat in Barcelona, in particular further control over its own taxation. In 2006 the then Socialist government of Jose Luis Zapatero negotiated a deal on further autonomy with the Catalans but this was blocked by the Spanish courts as unconstitutional after a move by the right wing centralist Partido Popular (PP).

With the PP in government further negotiation has proved futile, leading the Catalan nationalists to run a ‘consultative referendum’ on independence in 2014, and to declare a binding referendum on separation in October 2017.

The response of both the Madrid government and the Courts system both in Spain and in Catalonia has been to declare the referendum and the planned unilateral declaration of independence illegal. The dispatch of riot police to prevent the referendum, though producing some arresting scenes of violence, was largely a failure.[7]

The Catalan police, the Mossos d’Esquadra, in most cases did not impede the vote – contrary to orders from Madrid – with the result that over 2 million votes (though still only about 38% of the Catalan electorate) were counted for independence. Carles Puigdemont the president of the Generalitat has promised to unilaterally declare independence.

If, in most of this piece, I have suggested that there are few direct parallels between Ireland’s history and Catalonia’s, to Irish eyes, one obvious similarity stands out. In 1918 most of Ireland voted for the Sinn Fein party (though only about 40% of the electorate). They went on to declare an Irish Republic to be in existence. The British declared their parliament to be an illegal assembly. There followed four years of guerrilla war and the partition of the country.

While in Ireland we now tend to celebrate these events they actually highlight the terrible dangers implicit in the current standoff in Catalonia.

For when two states claim sovereignty over the same territory at the same time, the next recourse is force.

References

[1] Maire Ni Bhrian BMH WS 363

[2] Geoffrey Parker, The Global Crisis, p267

[3] See Michael Eaude, Catalonia, a Cultural History, p 61

[4] See Euade, Catalonia a Cultural History, p226-230

[5] See, Casilda Guell, The Failure of Catalanist Opposition to Franco (1939-1950), p48-50

[6] Guell, p.66

[7] For a good summary see veteran Irish reporter Paddy Woodworth’s piece in the Irish Times, https://www.irishtimes.com/opinion/paddy-woodworth-rajoy-has-played-into-the-hands-of-catalan-nationalism-1.3240965