The 1798 Rebellion – a brief overview

An overview of the insurrection of 1798, by John Dorney.

The 1798 rebellion was an insurrection launched by the United Irishmen, an underground republican society, aimed at overthrowing the Kingdom of Ireland, severing the connection with Great Britain and establishing an Irish Republic based on the principles of the French Revolution.

The rebellion failed in its aim to launch a coordinated nationwide uprising. There were instead isolated outbreaks of rebellion in county Wexford, other Leinster counties, counties Antrim and Down in the north and after the landing of a French expeditionary force, in county Mayo in the west.

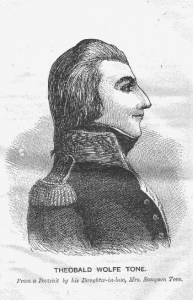

The military uprising was put down with great bloodshed in the summer of 1798. Some of its leaders, notably Wolfe Tone were killed or died in imprisonment, while many others were exiled.

The 1798 rebellion was failed attempt to found a secular independent Irish Republic.

The 1790s marked an exceptional event in Irish history because the United Irishmen were a secular organisation with significant support both among Catholics and Protestants, including Protestants in the northern province of Ulster.

However, the unity of Catholics and Protestants was far from universal and the fighting itself was marked in places by sectarian atrocities.

As a result of the uprising, the Irish Parliament, which had existed since the 13th century, was abolished and under the Act of Union (1800) Ireland was to be ruled directly from London until 1922.

Background

In the 18th century, Ireland was a Kingdom in its own right, under the Kings of England. Executive power was largely in the hands of the Lord Lieutenant and the Chief Secretary, appointed by the British prime minister.

However, Ireland also had its own parliament, which throughout the century, lobbied for greater control over trade and law making in Ireland. The Irish parliament was subservient to the British parliament at Westminster, but increasingly, as the century wore on, agitated for greater autonomy.

In 1782, under ‘Patriots’ such as Henry Grattan, the Irish parliament managed to free itself from subservience to the Lord Lieutenant and, to an extent, from the British parliament through the passage of laws that enabled it to make its own laws for the first time without reference to Westminster.

Ireland in the 18th century had its own parliament but the majority of the population was excluded from political participation on religious and property grounds.

However, membership of the parliament was confined to members of the Anglican Church of Ireland, which, allowing for some conversions, was overwhelmingly composed of descendants of English settlers. The parliament was not a democratic body; elections were relatively infrequent, seats could be purchased and the number of voters was small and confined to wealthy, property-owning Protestants.

Under the Penal Laws, enacted after the Catholic defeat in the Jacobite-Williamite war of the 1690s, all those who refused to acknowledge the English King as head of their Church – therefore Catholic and Presbyterians – were barred not only from the parliament but from any public position or service in the Army.

Catholic owned lands were also confiscated for alleged political disloyalty throughout the 17th century. Catholics, to a large extent the descendants of the pre-seventeenth century Irish population, also suffered from restrictions on landholding, inheritance, entering the professions and the right to bear arms.

Presbyterians, mostly descendants of Scottish immigrants, while not excluded as rigorously as Catholics from public life, also suffered from discrimination – marriages performed by their clergy were not legally recognised for instance.

Although some of the Penal Laws were relaxed in 1782, allowing new Catholic churches and schools to open, and allowing Catholics into the professions and to purchase land, the great majority of the Irish population was still excluded from political power, and to a large extent from wealth and landholding also, as the last decade of the 18th century dawned.

Discontent among Catholics was exacerbated by economic hardship and by tithes, compulsory taxes that people of all religions had to pay, for the upkeep of the established, Protestant Church.

Initially the United Irishmen, founded, mainly by Presbyterians in Belfast in 1791, campaigned merely for reform, lobbying for the vote to be extended to Catholics and to non-property holders. The United Irishmen had a determinedly non-sectarian outlook, their motto being, as their leading member Theobald Wolfe Tone put it, ‘to unite Catholic Protestant and Dissenter under the common name of Irishman’.

The United Irishmen, inspired by the American and French revolutions, initially lobbied for democratic reform.

They were greatly inspired by the events of the American and French revolutions (1776 and 1789 respectively) and hoped to eventually found a self-governing, secular Irish state on the basis of universal male suffrage. The leadership of the United Irishmen was largely Protestant or Presbyterian at the start and it recruited men of all sects, mainly in the richer, more urban, eastern half of the country.

Some of their early demands were granted by the Irish parliament, for example Catholics were given the right to vote in 1793, as well as the right to attend university, obtain degrees and to serve in the military and civil service.

However the reforms did not go nearly as far as the radicals wished. Catholics still could not sit in the Parliament for example, nor hold public office and the vote was granted only to holders of property worth over forty shillings a year.

Radicalisation

The United Irishmen did not remain an open reformist organisation for long. The French revolution took a radical turn in 1791. In the following two years it deposed King Louis XVI and declared a Republic. Britain and revolutionary France went to war in 1793.

In Ireland, the United Irishmen, who supported the French Republic, were banned and went underground in 1794. Wolfe Tone went into exile, first in America and then in France, where he lobbied for military aid for revolution in Ireland.

The United Irishmen now stated that their goal was a fully independent Irish Republic.

At the same time, popular discontent was growing, driven by economic hardship but also state repression, as the government dispatched troops to suppress the United Irishmen and other ‘seditious’ groups. The government also announced that men had to serve in the militia which would maintain internal security in Ireland during the war with France. Resistance to impressment into the militia led to fierce rioting in 1793 that left over 200 people dead.

Having been driven underground, the United Irishmen in Ireland began organising a clandestine military structure. In an effort to recruit more foot soldiers for the hoped-for revolution, they made contact with a Catholic secret society, the Defenders, who had been engaged in low level fighting, especially in the north, with Protestant groups such as the so called Peep of Day Boys and the newly founded Orange Order.

As a result, while the majority of the United Irishmen’s top leadership remained Protestant, their foot soldiers, except in north east Ulster, became increasingly Catholic.

That said, the Catholic Church itself was opposed to the ‘atheistical’ Republicans and was, for the first time, courted by the authorities, being granted the right to open a college for the education of priests in Maynooth in 1795.

A liberal Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, Earl William Fitzwilliam, was appointed in January 1795, with an agenda of passing the proposal by Henry Grattan for full Catholic Emancipation, including the right of Catholics to sit in parliament, to head off discontent. However, much to the dismay of liberals and Catholics in Ireland, Fitzwilliam was recalled in March of that year, after just three months in office, by the Prime Minister, William Pitt, who feared alienating the Protestant ruling class in Ireland while war raged with revolutionary France.

Fitzwilliam had replaced the hardline conservative Irish cabinet of John Fitzgibbon, John Foster and John Beresford, whom radicals nickamned the ‘junta’, and replaced them with liberals such as Henry Grattan. Once Fitzwilliam was replaced, however, his successors as Lord Lieutenant, Camden and then Westmoreland, reinstated the ‘junta’ who proceeded with a policy of repression. Many in hindsight saw the recall of Fitzwilliam as the squandering of the last opportunity to head off violent conflict in Ireland in the 1790s.

In 1796 revolutionary France dispatched a large invasion fleet, with nearly 14,000 troops, and accompanied by Wolfe Tone, to Ireland. By sheer chance, invasion was averted when the fleet ran into storms and part of it was wrecked off Bantry Bay in County Cork. Battered by the weather and after losing many men drowned, they had to return to France.

The United Irishmen were banned after Britain went to war with France in 1793 and went underground.

The government in Dublin, startled by the near-invasion, responded with a vicious wave of repression, passing an Insurrection Act that suspended habeas corpus and other peacetime laws.

Using both British troops, militia and a newly recruited, mostly Protestant and fiercely loyalist, force known as the Yeomanry, government forces attempted to terrorise any would-be revolutionaries in Ireland who might aid the French in the event of another invasion. The Crown forces’ methods including burning of houses and Catholic churches, summary executions and the practice of ‘pitch-capping’ whereby lit tar was placed on a victim’s scalp.

By the summer of 1798, the United Irishmen, under severe pressure from their own supporters to act, planned a co-ordinated nationwide uprising, aimed at overthrowing the government in Dublin, severing the connection with Britain and founding an Irish Republic.

The Rebellion breaks out

The rebellion was intended to be signalled by the stopping of all mail coaches out of Dublin on May 23, 1798.

However, the authorities in Dublin were aware of the plans and on the eve of the rebellion arrested most of the senior United Irishmen leadership. Their most senior leader in Ireland, Edward Fitzgerald was shot and mortally wounded during his arrest.

While mail coaches were stopped in some areas, other areas had no notice of the planned insurrection and with the United Irish leadership mostly in prison or in exile, the rising flared up in in a localised and uncoordinated manner.

Large bodies of United Irishmen rose in arms in the counties around Dublin; Kildare, Wicklow, Carlow and Meath, in response to the stopping of the mail coaches, but Dublin city itself, which was heavily garrisoned and placed under martial law, did not stir.

The Rising was uncoordinated as most of the United Irish leaders had been imprisoned.

The first rebellions resulted in some sharp fighting but the poorly armed (they mostly had home-made pikes) and poorly led insurgents were defeated by British, militia and Yeomanry troops. In many cases, captured or surrendering rebels were massacred by vengeful government forces.

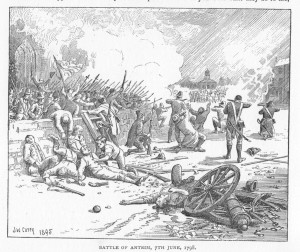

Wexford, Ulster and Kilalla

Only in County Wexford did the United Irishmen meet with success. There, after rising on May 27, the insurgents defeated some militia and Yeomanry units and took the towns of Enniscorthy and Wexford.

The leadership of the Wexford rebels was both Catholic and Protestant (the leader was the Protestant Harvey Bagenal), but included some Catholic priests such as father John Murphy and the rank and file were largely Catholic, in many cases enraged by the sectarian atrocities committed in the previous months by the Yeomonary.

The rebels failed to take the towns of New Ross and Arklow despite determined and costly assaults and remained bottled up in Ireland’s south eastern corner. In response to the government forces’ killing of prisoners at New Ross, the rebels killed over 100 local loyalists at Scullabogue and another 100 at Wexford Bridge. The fighting in the rebellion was marked by an extreme ideological and, increasingly, sectarian, bitterness. Prisoners on both sides were commonly killed after battle.

The rebels in Wexford held most of the country for a month before being defeated at Vinegar Hill.

The Wexford rebellion was smashed about a month after it broke out, when over 13,000 British troops converged on the main rebel camp at Vinegar Hill on June 21, 1798 and broke up, though failed to trap, the main rebel army. Some elements attempted to spread the rebellion into couny Kilkenny while others attempted to join up with United Irishmen in counties Kildare and Meath, before finally seeking refuge in the Wicklow mountains. Guerrilla fighting continued, but the main rebel stronghold had fallen.

In the north, the mainly Presbyterian United Irishmen there launched their own uprisings in counties Antrim and Down, in support of Wexford in early June, but again, after some initial success, were defeated by government troops and militia. Their leaders, Henry Joy McCracken and Henry Munro, were captured and hanged.

There was also a brief outbreak of rebellion in west County Cork, which was swiftly put down after a skirmish near Clonakility.

The last act of the rebellion came in August 1798, when a small French expeditionary force of 1,500 men landed at Killalla Bay in county Mayo.

Led by General Humbert, they defeated a British force at Castlebar, but were themselves defeated and forced to surrender at Ballinamuck. While the French soldiers were allowed to surrender, the Irish insurgents who accompanied them were massacred.

Another, final, French attempt to land an expeditionary force in Ireland, accompanied by United Irish leader Wolfe Tone, was intercepted and defeated in a sea battle by the Royal Navy near Tory Island off the Donegal coast in October. Tone was captured along with over 2,000 French servicemen. Sentenced to death, Tone took his own life in prison in Dublin.

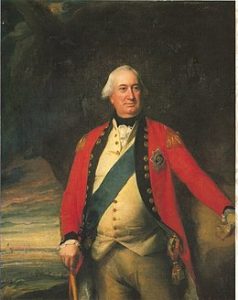

Lord Cornwallis, the new Lord Lieutenant, sent to deal with the rebellion, tried, after the fighting had ended, to end the bloodshed and reprisals by government forces.

He signalled this by forgoing execution of the other imprisoned United Irish leaders in return for their telling what they knew of the clandestine United Irish organisation. An amnesty and pardon was also declared for rank and file United Irishmen in return for the surrender of their weapons. Most did surrender, though some including Wicklow guerrilla Michael Dwyer, held out for several years after the rebellion, in his case only surrendering in 1803.

Aftermath

The main fighting in the 1798 rebellion lasted just three months, but the deaths ran into the tens of thousands. A high estimate of the death toll is 70,000 and the lowest one puts it at about 10,000. In addition, thousands more were injured and thousands of homes and farms were burned.

Thousands more former rebels were exiled in Scotland or transported to penal colonies in Australia. Others, such as Miles Byrne, went into exile serving in the French revolutionary and Napoleonic armies until 1815.

A brief rebellion led by Robert Emmet, younger brother of one of the 1798 United Irish leaders, in 1802 achieved little beyond Emmet’s own death by execution.

In 1800 the Irish parliament, under pressure from the British authorities, voted itself out if existence and Ireland was ruled directly from London from then until 1922.

It had been the hope of Cornwallis to accompany the Union with Catholic Emancipation, in order to secure Catholic support for the new United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. This did not happen however, due to entrenched opposition from conservative Irish Protestants and from the King, George III. It was not until 1829 that Catholics gained the right to sit in Parliament and to hold public office.

The Irish parliament was abolished in 1800 and Ireland ruled directly from London until 1922.

While the radicals of the 1790s had hoped that religious divisions in Ireland could be made a thing of the past, the fierce sectarian violence that took place on both sides during the rebellion actually hardened sectarian animosities. Many northern Presbyterians began to see the British connection as less potentially dangerous for them than an independent Ireland, where they would be a minority.

The United Irishmen’s hope of founding a secular, independent, democratic Irish Republic therefore ended in total defeat. But their foundation of the ideology of Irish republicanism would have a long and enduring legacy upon Irish politics.