Commemorating 1918 and the Self determination of Nations

Why celebrating the election of 1918 too enthusiastically might not be in the Irish state’s interests in 2018. By John Dorney

Why celebrating the election of 1918 too enthusiastically might not be in the Irish state’s interests in 2018. By John Dorney

The year 2018 is the centenary of one of the most important years in modern Irish history. Nineteen eighteen saw not only the end of the Great War, but, in Ireland, the decisive tipping point towards independence from Britain and ultimately, the partition of the country.

Nineteen eighteen, much more than the Rising of 1916, was the origin of the modern, democratic, independent, Irish state.

While 1918 may not have the glamour of the failed but romantic insurrection (romantic that is, in hindsight) of 1916, its events are, in many ways, at least as important, if not more so.

For it was in April of that year that the Irish public decisively rejected participation in Britain’s war effort, resisting successfully, through mass mobilisation, passive resistance and a general strike, an attempt to impose conscription on Ireland.

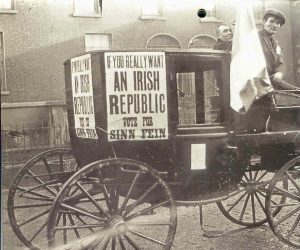

Even more importantly, at the end of the war, in the most democratic election up to that date in the United Kingdom, the Irish electorate voted overwhelmingly for the separatist party Sinn Fein. This despite the fact that many Sinn Fein leaders had been arrested in May of that year, on very flimsy charges of ‘plotting’ with the Germans to aid their war effort.

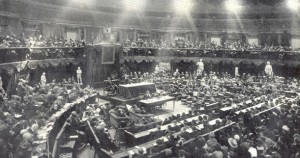

Sinn Fein took their victory their victory in the election of December 1918 to be a mandate for complete independence and, in January of the following year, duly declared the Irish Republic and its parliament the Dail, to be legitimate government of Ireland.

Initially it was hoped that this would secure Ireland a place in the post war Peace Conference, on the basis of American President Woodrow Wilson’s stated goal of self-determination for all nations, but even if it did not, in the words of Sinn Fein activist PS O’Hegarty;

‘It declared to the British that they had no claim to Ireland which was not rendered null and void by the Irish people’s definitive repudiation of any such claim, and that the only just and constitutional government in Ireland was the Government of Dail Eireann, which was elected by the people and represented the people’. [1]

Here, much more than the secret conspiracy of 1916, was the origin of the modern democratic, independent, Irish state. So, at any rate, have argued all shades of Irish nationalism ever since.

And yet, so far, official soundings on commemorations of 1918 have been muted. The only official commemoration noted so far has been a project to commemorate the extension of the franchise to women in that election. Some of this reluctance, no doubt, is due to preoccupation with more pressing contemporary matters – managing Britain’s exit from the European Union and its fallout in Ireland, dealing with a spiraling increase in the cost of housing and rent, and dealing with a potentially very divisive referendum on abortion.

However, commemorating the legacy of 1918 in Ireland may also present some very modern problems in 2018.

Self-determination of nations

If the principle to be celebrated in Sinn Fein’s electoral victory of 1918 is that, on the basis of the democratic will of the majority, Ireland could unilaterally declare independence, this poses some rather uncomfortable modern difficulties for the Irish government.

The 1918 election was the most democratic election in Ireland up to that date. The franchise was expanded, under the Representation of the People Act, from one including only property-holding men, to one that gave the vote all men over 21 and women over 30. Under the new franchise the electorate in Ireland was almost tripled, from 700,000 to over two million, and in contested constituencies there was a turnout of around 68 per cent.[2]

The December 1918 election was far more democratic than any that had preceded it but it still had some very significant shortfalls.

However while the December 1918 election was far more democratic than any that had preceded it, it still had some very significant shortfalls to modern eyes.

For one thing in 25 constituencies, the Sinn Fein candidate was elected unopposed. Secondly, due to the first past the post system, Sinn Fein did much better than its share of the vote would allow under the proportional representation system that is used in Ireland today. In total Sinn Fein won 46 % of the popular vote in the December 1918 election but nearly 70% of the seats – 73 seats out of 105.[3]

In some of the uncontested constituencies, for instance in East Cavan, where Arthur Griffith had won a contested by-election the year before, Sinn Fein would almost certainly have won anyway.

Furthermore, there were fewer uncontested seats in 1918 than in the previous election in Ireland. In 1910, 64 out of 103 constituencies were uncontested, compared to 27 out of 105 in 1918.[4]

Still, looked at in this light, Sinn Fein’s mandate to act as the sole representative of the Irish people becomes somewhat more problematic.

Now translated into the present, the Irish government, should it commemorate the events of December 1918 and January 1919 too enthusiastically, could be drawn into a web of extrapolations which it would no doubt prefer to avoid.

Brexit

The first of these is that the implications that the Irish nationalist revolutionaries took from the 1918 election are a little too close to those taken by the British (or English) nationalist ‘Brexiteers’ from the British referendum on European Union membership of 2016.

The ‘Brexiteers’ argue that the British people voted for national self-determination and that there should be no compromise with ‘Brussels’ on, for instance, remaining in the common market and free trade area in Europe, nor guarantees given to the Irish government that there be no ‘hard border’ in Ireland.

Never mind, in their eyes, that the majority to leave the EU in the referendum was small – 51% to 49% – nor that other parts of the United Kingdom, Scotland and Northern Ireland, voted to remain in the EU. No, ‘the people have spoken’. Though it is doubtful if they would appreciate the comparison, in their single minded interpretation of a single vote, the Brexiteers could almost be Sinn Feiners of 1918 vintage.

Though it is doubtful if they would appreciate the comparison, the British ‘Brexiteers’ could almost be Sinn Feiners of 1918 vintage.

For the Irish government, by contrast, the task at hand is to minimise the disruption caused by ‘Brexit’, keeping open the border in Ireland and maintaining free trade and free movement of people between Ireland and Britain. In this sense, paradoxically, they have something in common with British politicians after 1918, trying to downgrade Irish aspirations from independence back to Home Rule or limited self-government.

Additionally the Irish government of Taoiseach Leo Varadkar upset both British Conservatives and Northern Irish unionists by its determined stand on the Irish border, demanding guarantees that it would not again be fortified or ‘hardened’ to trade, as a prerequisite to negotiations on Britain’s exit from the EU. While this stance is highly popular in Ireland, Varadkar will probably not be keen to further heighten anti-British sentiment by enthusiastic commemorations of 1918.

All of which makes commemorating 1918 sensitive enough. There is, however, another reason why, in 2018, the Irish government will not want to emphasise the principle of national self-determination being decided by strict majority votes. That reason is the ongoing political crisis in Catalonia and Spain.

Catalonia

On October 1, 2017 Catalan nationalists held a unilateral referendum on independence of their region from Spain. Despite a declared victory of 92% in favour of independence, the low turnout of 43% meant that the real result was about 38-40% in favour of separation from Spain.

On October 1, 2017 Catalan nationalists held a unilateral referendum on independence of their region from Spain. Despite a declared victory of 92% in favour of independence, the low turnout of 43% meant that the real result was about 38-40% in favour of separation from Spain.

The Spanish government under the centralist and Spanish nationalist Partido Popular declared the referendum illegal and deployed police from outside Catalonia to the region, in a failed, though quite violent, attempt to block the vote.

Subsequently they dissolved Catalonia’s regional government, the Generalitat, imprisoned a number of nationalist leaders – the nationalist leader Puigdemont is effectively in exile in Brussels to avoid arrest – and called fresh regional elections. Disastrously for the Madrid government, the regional elections were won, albeit narrowly, by Catalan nationalists, giving renewed legitimacy to their calls for independence.

The situation in Catalonia in 2018 mirrors very closely that of Ireland in 1918, but the Irish government has declared support for the unity of Spain.

While Brexit may be more prominent in the minds of Irish politicians and senior civil servants at the moment, the situation in Catalonia in fact mirrors much more closely the events in Ireland of 100 years ago. And like Ireland from 1919 onwards, the situation in Catalonia has an extremely dangerous potential to career off the rails of civil politics and towards violence, armed and otherwise, in the coming months.

Again, while enthusiastic commemoration of the Sinn Fein victory in 1918 and the declaration of an Irish Republic in 1919 would suggest that the Irish government should support the Catalans, the interests of the Irish government, as a responsible EU member state, concerned with maintaining the integrity of the Union of its constituent states, are quite the opposite.

The Irish Department of Foreign Affairs confined itself to a terse statement about ‘respecting the territorial integrity of Spain’;

We are all concerned about the crisis in Catalonia. Ireland respects the constitutional and territorial integrity of Spain and we do not accept or recognise the Catalan Unilateral Declaration of Independence.

The resolution of the current crisis needs to be within Spain’s constitutional framework and through Spain’s democratic institutions. Ireland supports efforts to resolve this crisis through lawful and peaceful means.[5]

Precisely the opposite of the principles of Sinn Fein in December 1918 – that revolutionary nationalists could unilaterally declare independence based on a strict, though not overwhelming, majority vote.

Up the Republic?

Finally, in Ireland itself, there remains a stubborn ‘legitimist’ republican minority, who will always argue that the result of the 1918 British general election – the last all-Ireland poll before partition – should still be taken as a democratic mandate for an all-Ireland Republic, invalidating both of the existing states in Ireland.

This claim at least, Irish governments have long experience in managing. Any official commemoration of the 1918 election or of the First Dail will portray the current (26 county) Republic of Ireland as the logical outcome of those years. They will argue that the democratic will of the Irish people, north and south, was expressed in the referendums approving the Good Friday Agreement of 1998.

It is no longer in the interests of the Irish state to support separatist nationalism elsewhere.

In conclusion then, the Irish state will have difficulty in fully endorsing the nationalist revolutionaries of 1918 in 2018, not because of the familiar alibi of fearing to encourage republican violence, but rather for a deeper reason.

The needs of the Irish state in 2018 are not after all for the ‘self-determination of the peoples’ but for the smooth management of multi-national federation that is the European Union.

Commemorating the principles of Sinn Fein’s declaration of independence in 1919 are, perhaps, more dangerous today than commemorating those of the insurrectionists of 1916 in 2016.

References

[1] PS O’Hegarty, the Victory of Sinn Fein, UCD, 2016, p23

[2] http://www.ark.ac.uk/elections/h1918.htm

[3] Michael Laffan, The Resurrection of Ireland, p.164

[4] Philpin, Charles H. E. Nationalism and Popular Protest in Ireland, p.415

[5] https://www.dfa.ie/news-and-media/press-releases/press-release-archive/2017/october/statement-on-catalonia/