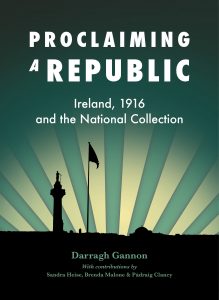

Book Review: Proclaiming a Republic: Ireland, 1916 and the National Collection,

By Darragh Gannon (with contributions by Sandra Heise, Brenda Malone and Pádraig Clancy)

By Darragh Gannon (with contributions by Sandra Heise, Brenda Malone and Pádraig Clancy)

Published by Irish Academic Press, (Newbridge, Co. Kildare: 2016)

Reviewer: Daniel Murray

Consider…

…The quirky egg-shaped ceramic salt dispenser which reads Laid at Westminster, 1912, HOME RULE, but won’t hatch in Ulster…

…The bullet-holed khaki hat which belonged to a man killed during the fighting in Moore Street…

…Countess Markievicz’s repeating pistol, which she kissed reverently before surrendering it…

…A silver cigarette case, inscribed by John MacBride on the 25th April 1916 while in the midst of the Easter Rising…

Darragh Gannon’s book is both a history of the Rising and an overview of the National Museum’s collection on 1916.

…and the many other fascinating objects on display, both in Collins Barracks as part of the National Museum’s exhibition, Proclaiming a Republic: The 1916 Rising, and between the pages of this book as the exhibition’s companion piece. Lavishly illustrated and skilfully written, the book superbly serves as a guide to this tumultuous period, in all its colour and complexity, as well as to the items on offer.

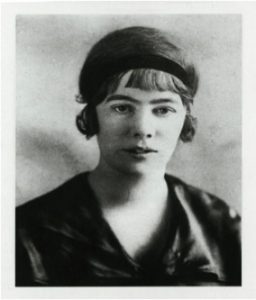

First established in 1935, based on the pioneering work of Nellie Gifford-Donnelly, the Museum’s collection grew within its first decade to a full 4,275 artefacts, most of which were from private donors. Not that parting was easy for some. Of her postcards from Tom Clarke, Countess Markievicz and Seán MacDermott, the Limerick republican Madge Daly wrote: “I am giving them to the Museum as I feel they will be of great interest in the future and that they should belong to the nation,” adding, “it hurts to part with them. The writers were all my dearest friends.”

Others were almost pugnacious about the historical record, particularly in regards to themselves. Sean Doyle, who had participated in the Rising in Wexford, explained his contributions to the Museum as intending to illustrate “the interesting part played by Wexford [which] has not been hitherto adequately represented.”

Others were almost pugnacious about the historical record, particularly in regards to themselves. Sean Doyle, who had participated in the Rising in Wexford, explained his contributions to the Museum as intending to illustrate “the interesting part played by Wexford [which] has not been hitherto adequately represented.”

By 2016, the collection compromised of over 15,000 items. Not everything had been accepted in the process; 10 out of the 25 items being loaned by the widow of Joseph Plunkett, such as his slippers, a cigarette case and a lock of his hair, were declined on the grounds that “they are purely personal items, adding nothing to historical knowledge and they should be retained in the family.”

A fear of the collection becoming overly familiar seems to have been an early concern, with a Director of the Museum questioning the value of displaying items which are “neither scientific nor artistic nor illustrating antiquity or industry.” But then, commemoration has long been a nervous question for the Irish state since its origin, made awkward in no small part due to the turbulence and recriminations against which it was birthed.

Commemoration has long been a nervous question for the Irish state since its origin, made awkward in no small part due to the turbulence and recriminations against which it was birthed.

Who was present at the annual ceremonies at Arbour Hill to mark the 1916 Rising depended on which party was in office. Opponents to the Treaty were barred from the Cumann na nGaedheal-led event in 1924. Later, when the political wheel had turned, attendance at Arbour Hill was limited to Fianna Fáil delegates and relatives of the rebels, causing over 200 previous invitees to find themselves struck off the guest list.

Times had changed by the 50th anniversary in 1966. The Easter Sunday parade outside the General Post Office (GPO) featured, along with the customary military personnel, a civic procession of 5,000 people representing language, labour, sporting and cultural interests. Keeping with this new spirit of inclusion, the official programme encouraged active communal engagement with the legacy of the Rising.

In this, the commemorations were following a trend, for the country was experiencing something it had not had for quite a while: a sense of self-confidence and a fresh engagement with the outside world, as per the policies of Seán Lemass, in his last year as Taoiseach in 1966. So striking were the events that year that the poet Dermot Boyle commented on how “for anyone who grew up in the 1960s, the Easter Rising meant 1966 and not 1916.”

Very different, again, were the subsequent years, overshadowed as they were by the Troubles in Northern Ireland, when the military ceremonies outside the GPO were discontinued between 1972 and 2005, save for a brief return for the 75th anniversary in 1991.

Very different, again, were the subsequent years, overshadowed as they were by the Troubles in Northern Ireland, when the military ceremonies outside the GPO were discontinued between 1972 and 2005, save for a brief return for the 75th anniversary in 1991.

The army parade returned for good for the 2006 commemorations, thanks to the renewed sense of self-assurance emanating from the Peace Process. Inclusivity was the watchword of the day, exemplified by an opening speech by Bertie Ahern as Taoiseach at the 1916 exhibition at the National Museum, entitled ‘Remembrance, Reconciliation, Renewal.’ Such commemoration was for the sake, Ahern said, of enabling Ireland to remember its past.

Of course, which past – and whose – remains an open question. At this book states: “The memory of the 1916 Rising, as projected by official state commemoration, has never been absolute.”

It is partly to challenge all and any orthodoxies that the Proclaiming a Republic exhibition items were selected.

It is partly to challenge all and any orthodoxies that the Proclaiming a Republic exhibition items were selected. The focus on items, many of such a personal nature, opens the period and the people who lived through it “to further reading. Objects such as ceramics, craftwork and clothing bespeak the primacy of the individual like no other historical source, effecting a truly democratic collection.”

Through the Uilleann piper’s uniform of Éamonn Ceannt, the watercolours by Countess Markievicz, and the tea-set used by Patrick and Willie Pearse, something more personal can be glimpsed other than icons of veneration to which the Rising leaders have sometimes been elevated, without allowance for any intimate nature.

Perhaps it was Nellie Gifford-Donnelly who said it best – and as a participant in the Rising, as well as a sister-in-law to Joseph Plunkett and Thomas MacDonagh, she had a lot to say. “Data is a cold affair, for the professors,” she said. “History will be cold on the warm, human motive that impelled them, towards their target, or the odd kinks, loves and capabilities – all, in short that makes the man live on.”