Women, the Vote and Nationalist Revolution in Ireland

Women, the right to vote and the struggle for Irish independence. By John Dorney

Women, the right to vote and the struggle for Irish independence. By John Dorney

This year, 2018, marks the centenary of women’s right to vote in Ireland. Under the Representation of the People Act in the British Parliament, voting rights were extended to all men over the age of 21 and to women. In the General Election of December 1918, women across the United Kingdom who were over 30 years of age and owned some property were, for the first time, entitled to vote.

In Ireland this came with a particular context. The country was in the grip of constitutional crisis over its status within the United Kingdom. Thus, the first woman elected to Westminster, Constance Markievicz, representing Sinn Fein, refused to take her seat and instead attended the rebel parliament, the First Dail, set up in Dublin in January 1919.

In the years that followed, 1919-1923, Ireland was to see upheaval, insurgency, nationalist revolution and Civil War. Irish women for the first time played an important role in politics, but most of them considered themselves part of a nationalist, not feminist movement.

Perhaps for this reason, the influence of women activists faded rather than increased after Irish independence.

Before 1918

Aside from their traditional role as mothers and wives and girlfriends of political figures, women had played some role in Irish politics before 1918.

In 1881 for instance, when Charles Stewart Parnell and other leaders of the Land League – the nationalist organisation that lobbied for tenants’ rights – were imprisoned. Parnell’s sisters Anna and Fanny took over the campaign of tenant farmers to withhold rents and resist eviction through their organisation the Ladies’ Land League.

Indeed the women were considered more militant than their male counterparts and of the British government’s conditions for releasing Parnell in 1882 was that the Ladies’ Land League be dissolved.[1]

Irish women played an important role in politics, but most of them considered themselves part of a nationalist, not feminist movement.

By the 1910s, women in Britain, the so-called suffragettes, led by activists such as Emeline Pankhurst, were campaigning for women’s right to vote. Women’s suffrage was one of the principal radical battlegrounds in British politics in the years leading up to the First World War.

The suffrage activists used sometimes violent direct action, such as throwing at hatchet at Prime Minister Asquith on a visit to Dublin in 1912 (it in fact hit and injured Irish Parliamentary Party leader John Redmond) to highlight their cause.

However, the women’s movement in Ireland could not escape the deep division caused by competing national aspirations. If women were to vote, was it as part of the United Kingdom or to a proposed Irish parliament in London? In Ireland, as result, there were two women’s suffrage leagues, one nationalist, led by Hanna Sheehy Skeffington and the other unionist. [2]

Women and Irish nationalism

The separatist newspaper Irish Freedom applauded militant suffragette action as consistent with their ‘fight for freedom’, but although some republicans, such as the socialist James Connolly were feminists, most nationalists were not.

The separatist newspaper Irish Freedom applauded militant suffragette action as consistent with their ‘fight for freedom’, but although some republicans, such as the socialist James Connolly were feminists, most nationalists were not.

The Irish Parliamentary Party’s leadership were generally against women’s suffrage, one leading member, John Dillon stating, ‘women’s suffrage will, I believe, be the ruin of our western civilisation. It will destroy the home, challenging the headship of man, laid down by God’.[3]

Despite this, or perhaps because of it – in order to stake a claim as equals in the nationalist struggle, most Irish feminists who were not unionists tended to put Irish independence before women’s rights. One might assume that politicised Irish nationalist women would also be ardent feminists and indeed, some such as Helena Molony, Maud Gonne and Constance Markievizc, were. In general however, most women nationalist movements, although in theory committed to universal suffrage subordinated it to the ‘national cause’.

The main women’s-only nationalist organization was Inghinidhe na hÉireann (Daughters of Ireland), formed in 1903 by Maude Gonne (a well-heeled English woman by origin but nevertheless a veteran of the Land War, and the Amnesty Campaign for Fenian prisoners) on the occasion of a Royal visit to Ireland in 1903.

According to Helena Molony, ‘It came into being as a, ‘counterblast to the orgy of flunkeyism which was displayed on that occasion, including the exploitation of the school children – to provide demonstrations of “loyalty” on behalf of the Irish natives.’ The Inghinidhe (satirically nicknamed the ‘ninnies’ by its detractors, with a roughly correct phonetic rendering of the name) organised a Patriotic Children’s Treat as rival to official parties held under the Union Jack for the Royal visit and claimed to have attracted 30,000 young patriots to it. [4]

They were, Molony recalled, ‘Irishwomen pledged to fight for the complete separation of Ireland from England, and the re-establishment of her ancient culture’. They also ran a campaign at one point to stop Irish girls from having sex with British soldiers.

According to Molony, ‘many thousands of innocent young country girls, up in Dublin, at domestic service mostly, were dazzled by these handsome and brilliant uniforms, with polite young men with English accents inside them – and dazzled often with disastrous results to themselves, but that is another side of the matter, and we were only concerned with the National political side’.[5]

According to Molony, ‘many thousands of innocent young country girls, up in Dublin, at domestic service mostly, were dazzled by these handsome and brilliant uniforms, with polite young men with English accents inside them – and dazzled often with disastrous results to themselves, but that is another side of the matter, and we were only concerned with the National political side’.[5]

Constance Marcievicz, like Maud Gonne, of aristocratic Anglo Irish background, founded Na Fianna Eireann in 1909, as a nationalist rival to Baden Powell’s ‘Imperialist’ Boy Scout movement.

Women separatists figured prominently in the Rising of 1916, but with some exceptions, generally not as combatants.

Nationalist women tended to assert their equality with the men by equal, or superior zeal in pursuit of Irish independence. Helena Molony thought that the pre-war Sinn Féin of Arthur Griffith, being, ‘definitely and explicitly against physical force’ was too moderate in the years before the First World War. ‘It all sounded dull, and a little bit vulgar to us’, she recalled. [6]

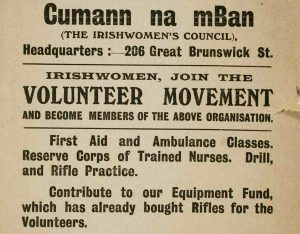

In 1913, parallel with the creation of the nationalist militia the Irish Volunteers, women created Cumann na mBan (roughly 1,500 strong) was formed to assist the Volunteers, absorbing many of the militants of Inghinidhe ha hÉireann, though some of the most radical of the latter, such as Helen Molony and Constance Markievicz, elected to join the socialist Irish Citizen Army instead, where they given equal standing with the men.[7]

In the Rising of 1916, Cumann na mBan and Citizen Army women were prominent, mostly as medics, nurses and messengers, but only a handful, notably Markievicz and Margaret Skinnider, actually took part in combat, the latter being badly wounded. Elizabeth O’Farrell, a Cumann na mBan member and nurse, took Pearse’s offer to surrender to the British military, though as Michael Barry has noted, she was literally airbrushed from history by photographers who captured the moment.

Though over 70 women were arrested at Easter 1916, unlike the men, they were, for the most part, released within a short time. The main exception was Constance Markievicz, who had shot dead a policeman in the Rising. However, like the male prisoners, she was released under a general amnesty in 1917.

Women also played an increased role in the separatist movement immediately after the Rising, with so many male activists dead or imprisoned. Kathleen Clarke, the widow of Tom, was the first to organise a fund for the families of prisoners.

In 1918, women were prominently involved in the successful campaign against conscription and in May of that year, the British arrested many prominent female activists including Kathleen Clarke and Constance Markievicz, along with male leaders such as Eamon de Valera, for conspiring in an alleged ‘German plot’.

Other women separatists such as Helena Molony and the doctor Kathleen Lynn had to go on the run to avoid arrest, many, including Lynn were to forefront in social activism at this time, helping to nurse victims of the ‘flu’ epidemic.[8]

Thus by the time women received the right to vote in Ireland in 1918, there was a perception that women were supporters of militant nationalism. While at this stage this was a gross exaggeration, it is possible that the majority of the relatively small pool of committed female activists, certainly in the south of Ireland, were involved in the separatist movement by this time.

The election of 1918 and after

In December 1918, a month after the end of the Great War, the United Kingdom held its first-ever general election with almost universal adult suffrage.

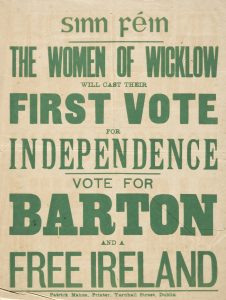

Sinn Féin, running on a promise to withdraw from the British parliament and set up a rival Irish one, buried the moderate Irish Parliamentary Party.

The separatists won 73 seats out of 105 and just under 50 per cent of the vote – though as many constituencies were uncontested this underestimated their actual support considerably.[9]

For the first time, all adult men over twenty-one and women over thirty-one (though women, unlike men, were still subject to some property restrictions) had the vote. Under the new franchise, the electorate in Ireland was almost tripled, from 700,000 to over two million.[10] It is impossible to state of course, under a secret ballot, how women voted, but most, certainly outside north east Ulster, must have cast their vote for Sinn Fein.

Under he Representation of the People Act, women over 30 received the right to vote in 1918 and the first woman MP was Sinn Fein candidate Constance Markievicz.

Constance Markievicz was the first woman elected as an MP in the United Kingdom, but like all Sinn Fein candidates, she refused to take her seat in Westminster. Nor could she take her seat in the First Dail, or unilaterally declared Irish Republican parliament, because she was imprisoned at the time in Holloway Prison in England. Markievicz was released in 1920 and served as Minister for Labour under the underground government of the First Dail.

As the British government banned the Dail and as the Volunteers or IRA increasingly engaged in attacks on the Royal Irish Constabulary, the political crisis in Ireland soon lurched into an insurgency that we now call the Irish War of Independence.

The women’s organisation, Cumann na mBan, was always subservient to the male-only IRA, but Republican women did play an important role in the War of Independence. One aspect of their role was social activism, which helped to shore up political support for Republicans.

Máire Comerford recalled that women doctors, Kathleen Lynn and Catherine Ffrench Mullen, set up temporary hospitals and ‘battled disease among the children of the awful slums of Dublin’. Áine Ceannt was head of the White Cross, the Republican Prisoners welfare organisation.

Cumann na mBan also carried clandestine messages to IRA commanders; fed the men in safe houses and manned the mass protests that took place outside Mountjoy Gaol and other prisons when Volunteers were executed. Female activists also typically provided the staff of the Republican Courts, where they functioned.[11]

The women also, in large part, directed the Republican propaganda effort. Maire Comerford remembered that Dorothy Macardle and Charlotte Despard, living in a flat owned by ‘Madame MacBride (Maud Gonne), wrote much of the ‘Irish Bulletin’ newsletter, and that ‘the British dreaded their pens as much as they dreaded an IRA column in the field’.[12]

Unlike the men, they were rarely on the receiving end of direct violence at the hands of British state forces and generally speaking, within the Republican movement, they were not expected to perform a military role. While around 6,000 men were imprisoned by the British by July 1921, only seventeen women were imprisoned.[13]

In May 1921, the British held elections for a proposed parliament of ‘Southern Ireland’. Sinn Fein ignored the formal legal structures of the election and contested it as an election for the Second Dail. This time six women were elected, though all were unopposed: Mary MacSwiney of Cork, Constance Markievicz, Kathleen Clarke and Margaret Pearse of Dublin and Kathleen O’Callaghan of Limerick and Ada English for the national University of Ireland.

Though this would appear to show strong progress for women’s role in politics, most were elected on the basis of their relation to a nationalist ‘martyr’. Of those six, all apart from English and Markievicz had seen their husbands or in Pearse and MacSwiney’s case, their brothers, killed by the British in the preceding years.

Women and Treaty split

The War of Independence was ended with the Anglo-Irish Treaty, which did not deliver the Republic proclaimed in 1919 but did allow a self-governing 26 county Irish Free State. Acceptance of the Treaty brought about a bitter split in Republican ranks.

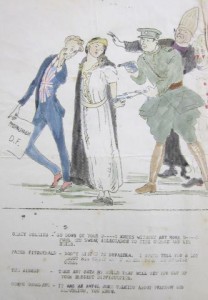

Some commentators put the bitter split in the nationalist movement over the Treaty and the subsequent Civil War down to the rantings of ‘hysterical women’.

Pro-Treaty politician, P.S. O‘Hegarty, wrote that Republican women were ‘harpies, ill-suited for rational political discourse’. While, during the Civil War, W.T. Cosgrave called them, ‘neurotic girls [who] are among the most active adherents to the Irregular [anti-Treaty] cause’.[14]

The first Republican group to openly split over the Anglo-Irish Treaty was Cumann na mBan. In the Dáil vote on the Treaty, all five women TDs voted against it: On 11 January 1922, the Cumann na mBan Executive voted by 24–2 to reject the Treaty. The two dissenters were Jennie Wyse Power and Miss Mullan from Monaghan.

Cumann na mBan came out strongly against the Treaty of 1921, but not all women were staunch anti-Treatyites.

On 5 February at a Special Convention of the women’s movement, delegates voted 413–62 against accepting the Treaty.[15]

All of which appears to show that nationalist women were implacably opposed to compromise with the British. Máire Comerford, for instance, wrote that ‘most women, like myself were too intransigently Republican to make concessions’.[16]

This assumption was a common feature of representations of the Treaty split, on both sides. Anti-Treaty leader Éamon de Valera, for instance, in arguing against an early election in the Free State in early 1922, made the point that the electoral roll had not been updated since 1918, when women over thirty had first received the right to vote, meaning that many of what he assumed to be his female supporters would be disenfranchised.[17]

In Dáil debates on 2 March 1922, the anti-Treaty Republicans appealed for the voting age for women to be brought down from thirty, where it had stood in 1918, to twenty-one, as it was for men and the property restrictions abolished. Pro-Treaty leaders Griffith and Collins did not disagree in principle, but argued, playing for time, that the three months until the Free State’s first election was due was not enough time to update the register of voters.[18]

However, the Cumann na mBan that so emphatically rejected the Treaty was a rump organisation. In the period of the split, the women’s movement haemorrhaged members, its number of branches collapsing from over 800 down to 133. The pro-Treaty women, led by Jenny Wyse Power, left to form their own women’s group, Cumann na Saoirse (the League of Freedom) in March 1922. [19]

All women nationalists were not diehard Republicans. Rather the anti-Treatyities among the women’s movement dominated the Cumann na mBan leadership and their intransigence caused the organisation to shrink and to split. All of the female TDs lost their seats in the 1922 election.

There is also a broader point. Cumann na mBan cannot be taken to represent all women in Ireland in 1922. Some of the separatists’ bitterest enemies during the independence struggle had also been women, notably the ‘separation women’ who had male relatives in the British armed forces and who had rioted ferociously against Republican activists from before the Rising of 1916 right up to the elections of 1922.

With that said, women Republicans, in what remained of Cumann na mBan, did form a particularly militant strand of the anti-Treaty movement.

Women and the Civil War

Republican women played a more significant role in the Civil War than in the War of Independence, at times playing the role of active combatants. Ernie O’Malley later wrote, ‘During the Tan War the girls had always helped but they had never had sufficient status. Now [in the Civil War] they were our comrades, loyal, willing and incorruptible comrades’.[20]

In the Civil War, some Cumann na mBan women acted as combatants and many as very close auxiliaries of fighters on the anti-Treaty side.

Todd Andrews voiced his admiration for O’Malley’s secretary Madge Clifford, ‘a young Kerry woman…who was as well informed about every detail of the IRA as O’Malley himself’. For the first time he realised that, ‘women had role outside of the home. Hitherto I had regarded women as appendages to men, whose function it was to rear children, provide meals and clothes, keep the house clean and nurse men when they were sick. It had never occurred to me that they could operate successfully as administrators or political advisors’.[21]

Many pro-Treatyites blamed the Civil War on ‘mad women’. And conversely, a narrative of the Civil War exists whereby anti-Treaty women were victims of a misogynist, male, pro-Treaty establishment. One fact that has hardly ever been acknowledged, however, is that it was also a conflict between women – ‘sister against sister’ as well as ‘brother against brother’.

At the time of the split in Cumann na mBan over the Treaty, the pro-Treaty Republican women led by Jenny Wyse Power had split off to form their own organisation, Cumann na Saoirse. During the Civil War, Cumann na Saoirse acted in concert with the pro-Treaty forces, especially in Dublin, assisting in the searching and arrest of anti-Treaty women, to the extent that the ant-Treatyites bitterly nicknamed them ‘Cumann na Searchers’.

Jennie Wyse Power, a veteran suffrage campaigner and nationalist, as well as the leader of the pro-Treaty women and Alice Stopford Green, who had helped to plan the Howth gun running back in 1914, had to be granted an armed guard by the CID in early 1923 to protect them from their former comrades on the anti-Treaty side.[22]

The Civil War was also a war between women – Cumann na mBan on the anti-Treaty side and Cumann na Saoirse on the pro-Treaty.

When the 238 Republican female prisoners were forcibly removed from Kilmainham to the North Dublin Union, it was the pro-Treaty Cumann na Saoirse women who were to the forefront of what turned into a hand-to-hand fight between the women. According to the pro-Treaty report, ‘the prisoners viciously attacked the female attendants’ some of whom had to be surgically treated and one of whom was knocked unconscious.[23]

The Republican women told a very different story of the removals, writing that Máire Comerford was ‘badly beaten’, two other women were thrown down the stairs and one woman, Sorcha McDermott, was ‘knocked on the floor, stripped, held on the floor and beaten with her own shoes by five Cumann na Saoirse women.’ They were followed by the men the anti-Treatyites alleged were ‘the murder gang from Oriel House and Portobello’ who ‘pulled out the girls kicking, beating, dragging them down the staircase, some by the hair.’[24]

Women in independent Ireland

While women played in important role in the struggle for Irish independence, many were disillusioned with the results.

Feminists such as Helena Molony voiced their disappointment with the results of the national struggle. There were some gains for women, all of whom over the age of 21 got the right to vote in 1923, four years ahead of women in Britain.

However it was not until 1987 that the number of female TDs elected in 1921, five, was equalled. Between 1927 and 1977, only fourteen women TDs were elected to the Dail.

There was no revolution in the social and economic status of women in independent Ireland.

Politics in the Irish Free State, (after 1949, Republic of Ireland) was a man’s game.

Moreover, the economic and social conservatism that took hold after the Civil War also affected women’s rights. In the United Kingdom in 1923, women gained the right to petition for divorce on certain grounds. In the Free State by contrast, divorce was technically legal under the 1922 Constitution, but the Dáil declined to legislate for its implementation in 1925 and it was made unconstitutional in 1937. It was not legalised until a referendum in 1996. Contraception, legalised in the late 1920s in Britain, remained illegal in Ireland until 1980, condemning many women to having huge families.

The consensus in the new Irish state was that women’s role was in the home. In 1927, Kevin O’Higgins passed a bill excluding women from jury service on the basis that he did not want them exposed to disturbing cases.[25]

De Valera’s 1937 constitution stated that ‘by her life within the home, woman gives to the State a support without which the common good cannot be achieved… The State shall, therefore, endeavour to ensure that mothers shall not be obliged by economic necessity to engage in labour to the neglect of their duties in the home.’[26] There was certainly to be no revolution in women’s social status in the early decades of independent Ireland.

Kathleen O’Callaghan, a member of de Valera’s underground republican government in the Civil War wrote to him to protest, writing,

The articles relating to the status of women were a great disappointment to me, as they must have been to the many who hoped for the ‘equal rights and equal opportunities’ which the Proclamation of the Republic in 1916 guaranteed to all its citizens.

I would ask you to delete these clauses, because they are a betrayal of what was regarded by all loyal Irishwomen as the charter of their freedom. In the period of the war with England, 1916-1923, the Irish nation rose to the test as never before in its history, men and women serving alike.

There was no talk then of the inadequate strength of women, their differences of capacity, physical and moral and of social function and I am surprised that you, who lived through the period in intimate contact with the ordinary people of the nation and valued, I think, the splendid service of the women of the people, now include in this Draft Constitution, clauses which, however well-intentioned, will militate against women in a state based on their work and sacrifice.

Her pleas were ignored. The Republican women, who had played such an active part in the Civil War, never again recovered their prominence in Irish public life. Part of this was undoubtedly the atmosphere of social conservativism in the Free State after the Civil War, but part of it also was that the women had assumed great importance as part of a nationalist, not feminist movement.

Once the Republican movement lost its central relevance after 1924, so the anti-Treaty women too either, like Dorothy McCardle and even Constance Markievcz, became loyal followers of Fianna Fail and Eamon de Valera, or lapsed into obscurity on the fringes of radical Republican politics, like Maire Comerford or Charlotte Despard.[27]

Women’s search for political and social equality in Ireland in the twentieth century did not begin or end in 1918.

References

[1] https://www.historyireland.com/home-rule/anna-fanny-parnell/

[2] Come Here to Me! Website, “Severity for Suffragettes,” Dublin 1912, http://comeheretome.com/2013/01/18/severity-for-suffragettes-dublin-1912/, Irish Freedom, October 1912

[3] Cited in Cal McCarthy, Cumann na mBan and the Irish Revolution, p.100

[4] Helena Molony, Witness Statement BMH WS 391

[5] Ibid.

[6] All above quotations from Molony BMH

[7] Helena Molony, BMH WS 391; also McCarthy, Cumann na mBan and the Irish Revolution, pp.32-33

[8] Kathleen Lynn, BMH

[9] Laffan, The Resurrection of Ireland, p.164

[10] http://www.ark.ac.uk/elections/h1918.htm. Accessed 31/03/17.

[11] Máire Comerford Papers, UCD LA/18/17.

[12] Ibid. LA/18/23.

[13] Anne Mathews, Renegades: Irish Republican Women, 1900–1922 (Cork: Mercier Press, 2010), p. 261.

[14] Gavin Foster, The Irish Civil War and Society: Politics, Class and Conflict (New York: Palgrave and MacMillan, 2015), p. 33.

[15] Mathews, Renegades, pp. 311–15.

[16] Comerford Papers, UCD LA/18/36.

[17] De Valera Peace Proposals, April–May 1922, De Valera Papers UCD P150/1616.

[18] Dominic Price, The Flame and the Candle: War in Mayo 1919–24 (Cork: The Collins Press, 2012), p. 203.

[19] Mathews, Renegades, p. 315.

[20] O’Malley the Singing Flame p148

[21] Andrews, Dublin Made Me , p262-263

[22] McCarthy, Cumann na mBan, pp. 198–9. Strictly speaking they were guarded by the Protective Corps, CID list of protectees, Mulcahy Papers UCD P7/B/94.

[23] Report on North Dublin Union, June 1923, NA TAOIS/1369 Box 3.

[24] An Phoblacht, Dáily Bulletin, 9 May 1923 NLI MS 15,443.

[25] McCarthy, Kevin O’Higgins, pp.265-266

[26] https://www.constitution.ie/AttachmentDownload.ashx?mid=ee219062-2178-e211-a5a0-005056a32ee4

[27] For potted biographies of women nationalist revolutionaries after the Civil War see, Sinead McCoole, No ordinary women, Irish Female Activists in Revolutionary Years, 1900-1923, pp141-215