“The road for the cattle – the land for the People” The Castlefergus Cattle Drive and the death of IRA Volunteer John Ryan

Pádraig Óg Ó Ruairc looks at the shooting of IRA Volunteer John Ryan who was shot dead by the RIC at a time when the politics of the ‘land question’ and popular protest against Irish involvement in the First World War were entwined as part of the Republican struggle against British rule.

**The following is an extract from the new book “Volunteer John Ryan” which has just been published by The Volunteer John Ryan Centenary Committee.

Food shortages, protest and the political situation in Ireland in 1918

In 1918 whilst the First World War continued to rage, Europe was suffering from a near critical shortage of food and ‘Bread Riots’ broke out in many countries. The export of thousands of tonnes of food from Ireland to support the British war effort raised political tensions and terrifying memories of An tOcras Mór – the Great Famine.

In 1918 whilst the First World War continued to rage, Europe was suffering from a near critical shortage of food and ‘Bread Riots’ broke out in many countries. Ireland was no different.

In late 1917 members of the newly reformed republican political party, Sinn Féin, gathered in Ennis to form the ‘Sinn Féin Food Council’ to prevent the export of cattle, oats, potatoes, butter and other food stuffs from the county to Britain. In December the Sinn Féin Cumann in Ennis began distributing potatoes to the poor. Following on the lead given by the Clare Republicans, early in 1918 Sinn Féin Headquarters in Dublin established the national “People’s Food Committee” to campaign on the issue.

The Committee declared “Food grown by the farmers of Ireland was the property of the Irish nation, and the Irish people have the first claim upon it.” In large cities such as Dublin, Cork and Waterford members of the IRA mounted an anti-export campaign which saw IRA Volunteers commandeer livestock that were being herded to the docks for export. The animals were butchered and the meat was sold to the urban poor at affordable prices.

In the west the prospect of food shortages was made worse by the ‘Ranch System’ under which wealthy landowners who supported British rule and owned huge estates which they used for grazing cattle. This was a process that had intensified in the 1800’s and the tenant farmers who had been forced off their farms by wealthy landlords intent on creating huge cattle ranches and game reserves swelled the ranks of the Republican Movement.

“Food grown by the farmers of Ireland was the property of the Irish nation, and the Irish people have the first claim upon it.”

When the Fenians launched their rebellion against the British Government in 1867 they issued a proclamation which not only declared Irish Independence, and called for “universal suffrage” and the “complete separation of Church and State” – the 1867 Proclamation also sought to abolish the system of landlordism in Ireland

“Our rights and liberties have been trampled on by an alien aristocracy, who treating us as foes usurped our lands … The real owners of the soil were removed to make room for cattle and driven across the ocean to seek a means of living … our war is against the aristocratic locusts whether English or Irish who have eaten the verdue of our fields – against the aristocratic leeches who drain alike our blood.”

In the aftermath of the 1916 Rising the Republicans who followed in the tradition of the Fenians began demanding that the estates of wealthy landlords be broken up and the lands redistributed to poor farmers and used for growing food.

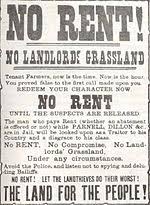

Cattle drives became common as large bodies of men often accompanied by Sinn Féin Clubs, local IRA Companies and band’s carrying Republican flags entered landlord’s estates ploughed the land and drove the cattle away with signs on their horns reading “The road for the cattle – the land for the People”.

Thousands of British soldiers were redeployed to Clare, Galway, Roscommon, Sligo and Tipperary as large bodies of men began seizing lands “by order of the Irish Republic”.

In February 1918, the same month that John Ryan was killed, the President of Sinn Féin, Eamonn de Valera, declared during a speech in Roscommon that: “Every Sinn Féin Club should be associated with a Company of Irish Volunteers (IRA) which may be used to prevent conscription to the British army and help divide the land evenly”.

Irish Republican Army’s involvement in ‘cattle drives’.

revolt against the emerging food crisis the Irish Republican Army were organising and training throughout Ireland and were seeking new opportunities to challenge the British Army and the British administration’s Police force in Ireland – Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC). Throughout 1917 the IRA throughout Ireland had been parading in public in open defiance of British rule and IRA officers were soon arrested en-masse and imprisoned.

Republican prisoners in Mountjoy Jail went on hunger strike to demand prisoner of war status.

In September 1916 the Republican leader and 1916 Rising veteran Thomas Ashe died whilst being force fed on hunger strike. Ashe’s death lead to a huge outpouring of sympathy for the Republicans and 30,000 people attended his funeral in Dublin. Realising that they could not risk creating further republican martyrs the British released the remaining prisoners and halted the arrests of others.

The leader of the IRA in County Clare, Michael Brennan, had been on hunger strike in Mountjoy Jail. When he was released following Ashe’s death he immediately returned to Clare and began looking for new ways to confront the British Forces and publicly defy their authority. “There was much agrarian discontent in Clare and we decided to ‘cash in’ on this. Cattle drives became very popular all over the county and IRA Volunteers took part in them as organised units. The Government reacted violently and excitement grew as fights developed between the IRA and the Royal Irish Constabulary.”

The IRA in Clare under Michael Brennan were heavily involved in ‘cattle driving’ to seize land for poor farmers.

Throughout January 1918 there were frequent cattle drives across Clare and many of these were organised by local IRA officers. At Kilfenora the IRA seized three large estates, redistributed thirty acres of land to local farmers and had part of each estate ploughed to grow food for the poor.

At Ennis cattle were driven from the lands of Dr Howard at Drumcliff and Tom Crewe at Loughivilla; both men were accused of being absentee landlords opposed to republicanism. At Broadford a force of RIC baton charged a group of men who were engaged in a cattle drive but they were beaten back with hurleys and sticks.

Michael Brennan’s plan to use IRA organised cattle drives to bring about a new conflict with the British authorities was working and by February the Clare Champion newspaper reported: “There is no longer even pretence of general respect for the authorities. The police are mocked and the magistrates are ridiculed with impunity.”

One of the most serious incidents happened at Scariff on 20th February when IRA Volunteers who were on a cattle drive attacked and disarmed members of the RIC. That morning IRA Volunteers armed with sticks and hurleys seized cattle belonging to Dr Samson at Moyone and General Gore at Bodyke.

The captured beasts were driven along the road to Scariff with placards affixed to their horns reading: ‘The land for the People – the road for the bullocks.’ At Scariff bridge the leading section of the IRA received word that three armed RIC men were on duty outside the National Bank about a hundred yards away on the road to Mountshannon.

Thomas McNamara and the leading IRA Volunteers from the Mountshannon Company decided to disarm the police and capture their carbine rifles: “As soon as the bank was reached we rushed the police. One of them tried to make off on his bike and as he did so I grabbed his carbine rifle and pulled it from him, at the same time knocking him to the ground. I gave this gun to Joe Tuohy of Feakle. Other IRA Volunteers disarmed a second policeman but the third man got away with his gun. He managed to get his back to the wall and fired a number of shots, which caused the crowd to scatter.”

The shooting of Volunteer John Ryan

On Sunday 24th February 1918 the Doora, Clarecastle and Newmarket-on-Fergus Companies of the IRA, with a group of civilian supporters over two hundred strong carried out a cattle drive on an estate at Manus about five miles from Ennis.

The protestors then moved on toward the Blood-Smyth estate at Ballykilty. The mansion house on the Blood-Smyth estate was being used at that time as an RIC Barracks. As the Republicans approached the estate they were confronted by the RIC garrison stationed there who opened fire on those taking part in cattle drive.

John Ryan was shot dead while leading a cattle drive on the Blood-Smythe estate near Ennis.

John Ryan was shot through the front of his neck and the bullet passed through his vertebrae partially severing his spinal cord. He was rushed to John Liddy’s house at Blackweir for emergency treatment. John Ryan was initially well enough to meet his father and tell him that he had seen an RIC Constable drop to one knee and take careful aim at him just before he was shot.

However Ryan’s condition quickly deteriorated and he died in the kitchen of Liddy’s House a short time later.

Born in 1898, John Ryan, was the second eldest of five children born to Thomas Ryan, a farm labourer, and his wife Margaret who lived at Ryan’s Cross, Crossagh, Newmarket-on-Fergus. John worked as a farm labourer and a domestic servant before joining the IRA

Three other men were wounded in the attack. Patrick O’Neill of Newmarket-On-Fergus was shot in the arm and had to be sent to Dublin for treatment. Martin Liddy was badly wounded in both arms the hip and back – he suffered from his injuries for many years afterwards and died prematurely in the 1920’s. Michael Murray (who had been one of the Mountjoy Hunger Strikers) had a lucky escape, he had been standing behind Ryan when he was fatally wounded and the bullet which passed through Ryan’s neck went through Murray’s hat grazing his head. (Murray proudly displayed the hat for decades afterwards in his shop in Newmarket-On-Fergus.)

John Ryan’s body was taken to the County Infirmary in Ennis and placed in the morgue there. For some reason there was a lengthy delay in securing a doctor to pronounce him dead and his date of death was mistakenly recorded as 1st March when the doctor completed the paper work rather than 24th February – the correct date of his death.

Two days after Ryan’s death the British Government declared all of Clare a ‘Special Military Area’

Two days after Ryan’s death the British Government declared all of Clare a ‘Special Military Area’ and introduced draconian measures aimed at supressing all political protest. A curfew was imposed on the people of Ennis and British soldiers patrolled the town’s streets. Fairs, markets and GAA matches were prohibited throughout Clare. Entry and travel through the county was restricted; all vehicles were searched and an RIC permit was needed to travel from one police sub-district to another. Political meetings were banned and all newspapers were subject to censorship including the Clare Champion which the British Army forced to cease publication for a brief period.

When Ryan’s body was eventually released for burial the British Army were determined now that Clare had been declared a “Special Military Area” to exercise their new powers to prevent any republican demonstrations at his funeral. Thousands of people travelled to Newmarket-On-Fergus to attend the funeral. Many of them were stopped and searched at British Army checkpoints and anyone found wearing Sinn Féin badges or carrying republican flags were not allowed to pass through the cordon.

The funeral procession estimated at two miles long brought John Ryan’s remains to his final resting place in Clonlohan Cemetary. A number of IRA Volunteers had managed to get through the British checkpoints and they draped Ryan’s coffin in the Republican tricolor flag and marched in military formation to his graveside. However the large British military presence at the graveyard initially prevented the IRA from burying their fallen comrade with full military honors. After the British soldiers and most of the mourners had departed a small group of IRA Volunteers reassembled and fired a volley of shots over Ryan’s grave.

The aftermath

Two dozen republicans were arrested by the RIC and put on trial in Ennis and charged with taking part in illegal land protests and cattle drives. However as soon as the trial began it was disrupted by Michael Brennan, the leader of the IRA’s East Clare Brigade, and his comrades who had packed the public gallery and began shouting “Up the Republic” “To Hell with England” “Up the Cattle Drives” and “The Land for the People”.

The judge ordered the gallery cleared, the protestors refused to go and a melee ensued. In the middle of the disruption Michael Brennan ordered the IRA prisoners in the dock to make a break for freedom and the RIC Constables guarding them were so shocked by the whole proceedings that they made no attempt to stop the escapees.

Fearing unrest and politically division between the landed and the landless supporters of Irish independence the national leadership of Sinn Féin and the IRA issued orders at the time of John Ryan’s shooting that Republicans should not participate in land seizures and cattle drives in-case they were seen by the public to be taking sides in private agrarian disputes and because it was felt that the cattle drives were distracting IRA Volunteers from other activities.

John Ryan’s death he was largely forgotten as many involved in the struggle for Irish Independence were embarrassed by their earlier association with cattle drives and agrarian protest.

In the years after John Ryan’s death he was largely forgotten because many of those involved in the struggle for Irish Independence had been embarrassed by their earlier association with cattle drives and agrarian protest. More importantly, the focus of commemoration had shifted to those who were killed in action fighting against the British Army, RIC Auxiliaries and Black and Tans. John Ryan’s grave in Clonlohan Cemetery was unmarked until the 1930’s when local Republicans erected a celtic cross over his final resting place bearing the inscription:

Erected by the Republicans of Thradaree, in memory of John Ryan of Crossagh, who was shot by the British Police at Castlefergus on the 24th February 1918 while striving to abolish the ranch system, aged 23 years. A croidhe ro-naofa Íosa dean trocaire ar a ánam.

On Sunday 25th February 2018 to mark the 100th anniversary of John Ryan’s death, The Volunteer John Ryan Centenary Committee, a group of local historians and republican activists from across East Clare and Limerick held a commemoration and unveiled a plaque at at Liddy’s house marking the site where he died.