The Boys of the Old Brigade – The IRA Third Northern Division

Kieran Glennon, author of From Pogrom to Civil War – Tom Glennon and the Belfast IRA, describes how this material charts the growth, then the disintegration of the 3rd Northern Division.

When discussing the Irish War of Independence and Civil War, one is more likely to think of the streets of Dublin or the mountains of Cork and Kerry than of Belfast.

For many years the 3rd Northern Division was little studied, either in terms of its composition or its activities – the IRA in Belfast and the surrounding areas is not one of the best-known guerrilla formations in the Irish revolutionary period. However, it was one of the formations most directly affected by perhaps the defining event of twentieth century Ireland: partition.

A range of new sources, particularly those in the Military Service Pensions Collection of Military Archives, now enables us to put together a detailed picture of the IRA in the north through the War of Independence, partition and the Civil War.

The 3rd Northern Division – background

The War of Independence came to the north when local units of the IRA participated in the nationwide burning of income tax offices at Easter 1920.

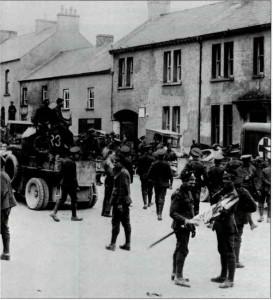

Raids for arms and attacks on barracks followed, but the outbreak of a pogrom against nationalists in the summer of 1920 forced the IRA into a more defensive posture as it tried to protect nationalist districts from loyalist attacks.

However, in the spring of 1921 there were ambushes on RIC “targets of opportunity” in Belfast and attacks on barracks in Antrim. While the scale of these offensive operations was inhibited by fear of the reprisals they would provoke, the nature of the campaign was broadly similar to that being waged elsewhere in the country.

The 3rd Northern Division developed from what had been the Belfast, Antrim & East Down Brigades of the Irish Volunteers.

The 3rd Northern Division developed from what had been the Belfast, Antrim & East Down Brigades of the Irish Volunteers. In the late spring of 1921, as part of the process of “divisionalisation” set in place nationally, these three Brigades were brought together under the umbrella of the 3rd Northern Division. Belfast provided the steering, with its Brigade O/C, Joe McKelvey, assuming command of the new Division.

In May 1922, the 3rd Northern took part in a general “northern offensive”, which was originally meant to involve all five Northern Divisions, aimed at overthrowing the unionist government in Northern Ireland. Assistance was lent from south of the border by both the pro- and anti-Treaty wings of the divided IRA – Michael Collins and Liam Lynch co-operated in the planning of this campaign.

However, the offensive collapsed within weeks and in the summer of 1922, men from the 2nd and 3rd Northern Divisions were brought to the Curragh camp in Kildare, ostensibly for training in preparation for the mounting of a new offensive.

For months, they were left with no clear indication from the Provisional Government as to its plans for them, but eventually, after a series of pleading letters sent by the O/C of 3rd Northern, Minister for Defence Richard Mulcahy replied: “I am not in a position to, nor do I see the necessity for saying more with regard to the question raised in your memo of 18th October, than that the policy of our Government here with respect to the North is the policy of the Treaty.” [1]

This marked the beginning of the end for the 3rd Northern Division. Shortly afterwards, some men began enlisting in the Free State Army, while the remainder began making their way back north, where – at best – they faced an uncertain future.

Pre-Truce membership

The Irish War of Independence ended with a Truce on 11th July 1921. On that date, the nominal rolls of membership of 3rd Northern units list 1,621 officers and men across the three Brigades and the Divisional Staff. [2]

To this can be added names from other sources, giving a total of 1,772 who had pre-Truce service.[3] Belfast predominated with 1,052 members, there were 285 in Antrim and 427 in East Down, with 8 on the Divisional Staff.

However, the number of active Volunteers was probably far smaller.

The nominal membership was considerably more than what even IRA GHQ at the time had believed to be the strength of each Brigade. Returns of numbers “on parade” provided to the Director of Organisation in the summer of 1921 show a total strength of less than 800 for the entire Division, less than half of the numbers compiled in the 1930s: 497 in Belfast, 111 in Antrim and 167 in East Down.[4]

The nominal strength of the 3rd Northern Division in 1921 was 1,700 men, but the active total noted by IRA GHQ was about 800.

The Belfast Brigade had two battalions: the 1st, based in the nationalist heartland of west Belfast, had six companies; the 2nd encompassed units from more isolated nationalist enclaves elsewhere in the city.[5]

Covering a much larger geographical area, the Antrim Brigade was divided into four battalions, roughly corresponding to the north, south, east and west of the county. However, describing these as “battalions” was somewhat grandiose, as none had even 100 members. Similarly, the East Down Brigade was split into four battalions, three clustered around either side of Strangford Lough and a fourth further south towards Castlewellan.

There was a strong family element to IRA membership, the most striking example being that of Edward, Charles, James, John and Joseph McEntee, all of King St in Belfast and all members of A Company, 1st Battalion.

Involvement also crossed generations – Hugh, Thomas and Joseph Gunn of Brighton Street were all members of the IRA while another Joseph Gunn, presumably a son of one of the others, was a member of the Fianna.

Extended families can also be seen outside Belfast – seven men named Lynn were members of the Ballycastle Company in Antrim, while it is not unreasonable to assume that the three men named Patrick McAuley who were all members of the Glenariffe Company would quite likely have shared a grandfather.

Trucileers

Following the Truce, IRA units across the country saw an influx of new recruits. Some of these had genuine reasons for not having enlisted prior to the Truce, while some undoubtedly only joined up when it was safe to do so in the hope that they could belatedly bask in whatever glory had been earned by the IRA over the previous years. All were described as “Trucileers” by the pre-Truce veterans.

However, in the north, recruitment to the IRA continued beyond the signing of the Truce because the fighting itself continued – as Belfast Brigade O/C Roger McCorley put it, “The pogrom lasted 2 years…the Truce itself lasted six hours only.” [6]

If we compare the numbers on the nominal rolls for 1st July 1922 to those at the time of the Truce, we can see how rapidly the 3rd Northern Division grew. The Antrim Brigade had the most rapid expansion, increasing by 65% to 471 men in July 1922. The East Down Brigade grew by 43% to reach 612 members.

The strength of the Division increased by over a third in the period after the Truce of July 1921.

Measuring the growth of the Belfast Brigade is complicated by the fact that many of its units had disbanded by July 1922. If we look at the 1st Battalion, it had grown by 21% to 804 members by that point.

But in the 2nd Battalion, by July 1922, B Company in Ballymacarrett was “only a skeleton company” with no members listed, while C and D Companies were described as “non-existent”, so comparisons between the two dates are impossible.[7] Two additional battalions were formed in Belfast in late August 1921, but these had also broken up by July 1922.

However, the very fact that two entirely new battalions had to be created would suggest that recruitment to the Belfast Brigade after the Truce was most likely on a par with that for the other two Brigades, especially as the worst of the violence in Belfast came after the Truce.

Even with some records missing, and some units no longer existing by July 1922, we can see that the Belfast Brigade expanded by a minimum of 25% after the Truce. Even this figure is an understatement as “…there are men who will not allow their names to appear on this list, owing to the nature of their employment.” [8] In total, the 3rd Northern Division grew by at least 36%, bringing its membership to just over 2,400.

To view this in context, it is worth looking at the pool of men from which the IRA could draw recruits.

The 1911 Census shows that in the whole of county Antrim in that year, there were only 12,605 catholic boys aged 10 (+/- 5 years) and only 11,142 catholic men aged 20 (+/- 5 years). [9] While equating religion with a republican political outlook is inherently flawed, especially given that the constitutional Nationalist Party was still the main opponent of unionism in the north, those would have been the key age groups from which the IRA would recruit in 1920-22. This suggests that roughly one in ten of potential members did join the 3rd Northern.

The split in the IRA

By the spring of 1922, the IRA had split over the Anglo-Irish Treaty. While Michael Collins and his colleagues set up a Provisional Government to implement the Treaty, many IRA officers vehemently rejected it.

On 26th March 1922, an IRA Army Convention met in Dublin, despite being banned by the Provisional Government; it was attended by Joe McKelvey in his then capacity as O/C 3rd Northern Division, and by each of the three Brigade O/Cs – Roger McCorley (Belfast), Tom Fitzpatrick (Antrim) and John Hughes (East Down).

The Convention repudiated not only the Treaty but also the authority of the Dáil which had approved it and of IRA GHQ, headed by Collins and Richard Mulcahy. Instead they appointed an Army Executive to oversee the IRA, with McKelvey being elected as a member of the Executive’s governing Army Council.

Desperate to win back the northern units, at a meeting in Beggars Bush Barracks after the Convention, pro-Treaty Chief of Staff Eoin O’Duffy promised McCorley and Fitzpatrick that the Provisional Government would supply them with arms and ammunition, so on foot of this undertaking, they agreed to recommend that their Brigades remain under the command of GHQ rather than the new Executive. [10]

From this point on, it can be said that there were two 3rd Northern Divisions – one loyal to pro-Treaty GHQ and the other loyal to the anti-Treaty Executive; the latter came to be known as the “Executive Forces”. It should not be assumed, however that the pro-GHQ 3rd Northern Division was necessarily pro-Treaty, as they were trenchantly opposed to accepting partition and the unionist government in Northern Ireland; rather, they were won over by the promise of military aid from the Provisional Government.

The 3rd Northern were trenchantly opposed to partition and the unionist government in Northern Ireland; but sided with the Pro-Treaty side led by Michael Collins due to the promise of military aid from the Provisional Government.

After McKelvey’s departure to the Executive, the former Divisional Adjutant, Seamus Woods, was elected O/C of the pro-GHQ 3rd Northern by a Divisional Council consisting of the Divisional Staff and the three Brigade O/Cs. [11] Woods had been seconded to O’Duffy’s office at GHQ the previous February, so he was obviously someone who O’Duffy felt could be trusted to keep the Division loyal – in fact, Woods later claimed that “I feel personally responsible for holding over 90% of the Division with GHQ…” [12]

The Executive, or anti-Treaty, 3rd Northern was commanded by Patrick Thornbury. He had originally been a member of C Company, 1st Battalion in Belfast but for nearly two years prior to the Truce he was attached to an IRA Officers’ Training Corps in Dublin; he had returned to Belfast after the Truce. [13]

Seamus Woods claimed that 90% of the Division was pro-GHQ; in the 1930s, the Brigade Committee for Belfast listed 420 men, out of a total of 1,307, as having taken the anti-Treaty or Executive side in the Treaty split. So, while not as overwhelming as Woods claimed, by nearly two to one the Belfast IRA was aligned with the pro-Treaty Provisional Government in mid-1922.[14]

Nor were all those listed as Executive Forces in July 1922 necessarily anti-Treaty: some two dozen later joined the pro-Treaty National Army in the Civil War, most notably Thomas Murphy from the Falls Road, who became a Staff Captain at Eastern Command HQ.[15]

Outside Belfast, the split appears to have little impact. In the returns for the Antrim Brigade on the second “critical date”, there was no mention whatsoever of the Executive Forces. The situation in East Down was curious – while there were returns made for the Brigade Staff and each of the battalions on that date, there was a second inclusion in the file, which stated that: “This Brigade did not exist at the second critical date (1st July ’22). The only IRA unit in this area after the split was known as the Downpatrick Active Service Unit and consisted of 16 men.” [16]

Just how active this unit was can certainly be questioned, as 8 of the 16 men listed had already been arrested and interned by the end of June. [17]

3rd Northern fatalities

Two factors contributed to a thinning of the 3rd Northern Division’s ranks throughout the pogrom period of 1920-22 – death and arrest.

Writing in 2008, historian Robert Lynch stated that:

“…despite later tales of the heroic defence of Catholic areas, the IRA did not suffer any notable casualties in defensive operations, which might be expected if members were on the front line as defenders. The fact is that no identifiable IRA members were killed or injured in rioting during the whole two years of the conflict. Those that were killed died largely at the hands of RIC murder gangs: extremist, secret loyalist groups within the police force.” [18]

Successive releases of files from the MSPC have since rendered this statement obsolete, but it was repeated verbatim in his contribution to The Atlas of the Irish Revolution in 2017.[19] In fact, twenty-one members of the Belfast Brigade and five members of the Fianna were killed in the city between July 1920 and June 1922 (two more Belfast IRA members were killed in other counties). In addition, five members of the Antrim Brigade were killed in May and June 1922.

Contrary to some historians, the majority of the 3rd Northern’s casualties were inflicted in action, many of them in street fighting to defend Catholic neighbourhoods.

Of those killed in Belfast, five were killed by the RIC’s “murder gang” acting in reprisal for IRA attacks. However, most IRA fatalities in the city did occur during rioting or in action.

For example, James Ledlie was killed in the rioting around the Falls Road that followed the Raglan St ambush just before the commencement of the Truce in July 1921 [20]. On 20th April 1922, John Walker was killed while attempting to repel an attack by Specials and a unionist mob on the Short Strand [21].

On 31st May 1922, following the disarming of a group of Specials in Millfield, during which one of them was killed, the escaping IRA party was pursued by armoured cars and George McCaughey was “riddled by Lewis gun fire” [22].

On 20th June 1922, during the latter stages of the IRA’s northern offensive, William Thornton was killed when confronted by the RUC in the act of fire-bombing a business premises in Gloucester St in the Markets area. [23]

As has been the case with previous releases of MSPC files, future releases may well show that other people killed in Belfast during the pogrom period, who had previously been thought to be civilians, were in fact members of the IRA.

In short, the idea that the IRA in Belfast did not suffer fatalities in street fighting and was therefore not involved in the defence of nationalist neighbourhoods is unsustainable.

The five deaths of IRA members in Antrim occurred in two incidents. On 24th May 1922, in the early days of the northern offensive, Charles McAllister and Pat McVeigh were killed in Glenarriffe during an attempted ambush on a patrol of B Specials.[24]

The three other IRA deaths the following month were more controversial: a joint patrol of British troops and Specials entered Cushendall, took three men prisoner and interrogated them, following which the three were shot dead.

At the time, it was claimed that all three were unarmed, although the mother of James McAllister was subsequently given a gratuity in acknowledgement of her son having been on IRA active service at the time. [25] John Gore and John Hill, the other two killed, were included in the nominal roll of members of the Glenarm Company of the Antrim Brigade’s 3rd Battalion.[26]

There were no East Down Brigade members killed. In many respects, this was the least warlike of the three Brigades in 3rd Northern; this is reflected in the low number of 1916-21 Campaign medals awarded – of the 153 medals awarded to former members of the 3rd Northern Division IRA and Fianna, only 5 were given to members of the East Down Brigade.

Arrests and internment

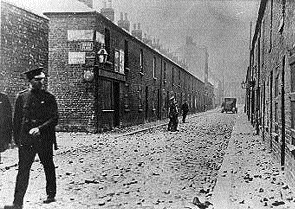

In response to the killing of Unionist MP William Twadell in Belfast on 22nd May 1922, the Northern Ireland government invoked the power of internment it held under the provisions of the Special Powers Act, passed six weeks earlier.

The initial impact on the 3rd Northern was limited – of the first 202 internees, only 41 were from Belfast, Antrim and Down and even these were not necessarily all IRA members [27]:

“A few IRA officers, generally of lower rank, were lifted. Far less than 10% of those arrested during and after the sweep were active members of the IRA. The vast majority of those arrested were nationalists and pro-Treaty.” [28]

But as the hunt for IRA suspects went on over time, more and more 3rd Northern members were interned. Eventually, 100 from the Belfast Brigade, 13 from Antrim and 28 from East Down would be captured, together representing 6% of the total Divisional strength – the Divisional Staff was particularly hard hit, with 4 of the 13 pre- and post-Truce members being detained. Altogether, of the 145 3rd Northern members interned, 19 were staff officers, at either Battalion, Brigade or Divisional level. [29]

The Northern Ireland government introduced internment in May 1922 and many IRA members were arrested. Others fled south.

Some of the internees had travelled surprising paths. At the time of the Truce, Rory Graham was a Staff Captain on the Divisional Staff; the son of a Presbyterian minister, he was the only Protestant among the 3rd Northern leadership: “He said that, being a Protestant, he was a sort of white blackbird as far as the Catholic Irish Volunteers were concerned. Eventually, however, he committed to join the Volunteers and was received into a company by Seán Óg O’Sullivan. That would be in 1917.” [30]

But the journey of Patrick Barnes was probably the most protracted and remarkable: he had been a member of the 1st Battalion, Royal Irish Rifles in the British Army at the start of the Great War and had received the Mons Star medal; wounded in the Battle of Ypres, he was granted an honourable discharge. [31]

He then enlisted in the Irish Volunteers and mobilised with the Belfast Battalion in Coalisland during the Easter Rising.[32] Prior to the Truce, he was a member of B Company, 1st Battalion in the Belfast Brigade and was later listed as a member of the Executive Forces at the start of July 1922.[33]

He was then a drill instructor for the 3rd Northern detachment in the Curragh and was known by the northern government to be stationed in the Curragh when his internment order was signed on 19th September. [34] Six days later, while home in Belfast, he was arrested and interned on the Argenta.

Despite claiming in March 1923 to have been be a member of the Free State Army, and provision of a letter from the 17th Battalion of the Army supporting his claim, he remained interned on foot of a recommendation against release “on any condition.” [35] He was eventually freed in December 1923, thus having been a member of each of the British Army, the Easter Rising Irish Volunteers, the pre-Truce IRA, the Executive IRA, the 3rd Northern contingent in the Curragh, the Free State Army and having been an internee.

Free State Army

According to Roger McCorley, when the men in the Curragh were told there would be no more offensive action undertaken against the northern government,

“We held a meeting with the Divisional O/Cs and Staffs and we decided that any man was free to go where he wanted, either to go home to the North or join the Free State Army … there was no pressure brought to bear on us whatsoever.” [36]

The Army Census, undertaken on the night of 12th – 13th November 1922, illustrates the degree to which the offer to join the Army was taken up.

In total, there were 624 men from Belfast, Antrim and East Down in the Army, but less than a third of these, 190 men, can be definitively correlated with men listed on the nominal rolls.

We know that others joined the Army after the Census, bringing the 3rd Northern total to 242 or roughly 10% of the total Divisional strength. Of those, 3 had been on the Divisional Staff, 153 were from Belfast, 57 from Antrim and only 28 from East Down, again illustrating that Brigade’s general lack of martial ardour.

Between the sending of Mulcahy’s abrupt memo on 20th October and the taking of the Census, the 3rd Northern contingent in the Curragh had begun to be broken up – this process applied particularly to the Belfast Brigade. This may have been done to defuse a potential mutiny, word of which had even reached Ernie O’Malley of the anti-Treaty IRA:

“I am in touch with a man in the Curragh and I have informed Aiken that I could get a message from him to any of the officers there. In fact some of the Northern men there are disaffected and about 100 of them are disarmed and more or less semi-prisoners.”[37]

By mid-November, there were only 179 men from the 3rd Northern area left in the Curragh, by now described as the 2nd & 3rd Northern Reserve, as it also included 251 men from the 2nd Northern Division in Derry and Tyrone. In this Reserve, Belfast men were in a minority, only 67 of the total, the remaining 112 being from Antrim and East Down.[38] 107 of this group can be found on the nominal rolls for the various 3rd Northern units.

Northern men fought on both sides of the south’s Civil War, but most served in the pro-Treaty National Army.

The largest group of men from the 3rd Northern area was in Dundalk, but by then, they were listed as being members of the 5th Northern Division. Here, there were 247 men from the 3rd Northern area, all but 19 of them from Belfast.[39] 53 of these can be identified from the nominal rolls.

In Wellington Barracks in Dublin, there was a third substantial group of 106 men from the 3rd Northern area, with all but 3 from Belfast. Most were still listed as being attached to 3rd Northern Division, although 13 were in the 2nd Eastern Division. Only 25 of this contingent can be found on the nominal rolls.[40]

In various other barracks around the country, there were a further 92 men from Belfast, Antrim and East Down, but as only 5 of these can be matched with the nominal rolls, it is likely that these were mainly men who came south independently after the start of the Civil War, rather than as part of the evacuation of the 3rd Northern after the failed May offensive. Their motivations for enlisting would have varied, covering everything from the desire for a secure wage to a simple sense of adventure.

However, in the case of the two Convery brothers from the Ormeau Road attached to the Dublin Guards in Beggars Bush, it is difficult to see a reason for enlisting other than sheer boyish enthusiasm – Gerald was aged 17 and his brother Patrick was only 16.[41]

Civil War

Members of the 3rd Northern Division took part on both sides during the Civil War.

Pat Thornbury, Divisional O/C of the Executive 3rd Northern, brought about 30 men down to Dublin at the request of anti-Treaty Dublin Brigade commander Oscar Traynor during the battle for Dublin in the first week of the Civil War.

This contingent was stationed first in Barry’s Hotel in Parnell St, then moved to the Gresham Hotel in O’Connell St, where they took part in the fighting after the capture of the Four Courts.[42]

Another Executive 3rd Northern member, Joseph Billings, who had been O/C of the Active Service Unit that mounted the Raglan St ambush in July 1921, was also stationed in Barry’s Hotel, as Barracks Adjutant.

When the hotel was evacuated after the fall of the Four Courts, he was in charge of removing the garrison’s store of weapons to a safe location, but owing to personal circumstances, resigned from the IRA afterwards.[43]

Michael Carolan, an Adjutant of 3rd Northern Division before the Truce, also opposed the Treaty. He was wounded in fighting on Grafton St in Dublin in July 1922. [44] On recovering from his wounds in the autumn, he took up a position of Director of Intelligence for the anti-Treaty IRA Eastern Command and in November, was promoted to be Director of Intelligence at anti-Treaty GHQ. [45]

On the other side, former 3rd Northern officers took part in some of the most worst episodes of the Civil War.

In one incident in Wicklow, while supposedly negotiating the surrender of surrounded Republicans, Felix McCorley, Roger’s brother and one-time Adjutant of the Antrim Brigade, was alleged to have suddenly shot their leader in the face and then fired a second round at the prone casualty, killing him.[46] However, McCorley’s family insisted that “there were different versions of that story.” [47]

In December 1922 the author’s grandfather, Tom Glennon, by then Adjutant of the 1st Northern Division in Donegal, was in charge of a party which shot and killed a prisoner who was attempting to escape; a second prisoner was wounded and recaptured.[48] The following month, Glennon was a member of the court martial which tried the men who would ultimately be executed as the “Drumboe Martyrs.”

The most tragic incident was the execution of Joe McKelvey in Mountjoy prison on 8th December 1922. He had been captured in the Four Courts the previous summer, but in reprisal for the killing of a pro-Treaty TD, he was sentenced to be executed, along with three other senior anti-Treaty leaders also in captivity, Rory O’Connor, Liam Mellows and Dick Barrett.

The officer in charge of the firing party was Thomas Gunn, who had been an officer in B Company, 1st Battalion in Belfast – McKelvey was thus to be executed by a firing squad led by one of his own former subordinates. The execution was botched, with McKelvey only wounded; according to Gunn’s grand-daughter, her father:

“…heard from his father that he was present at the death of Joe McKelvey. My Dad remembers his father telling him that the first bullet shot him below the heart and that Joe asked for another and Grandad went up to deliver the shot but his finger froze on the trigger and that Hugo MacNeill delivered a second bullet and that Joe had asked for another.” [49]

The 3rd Northern men stationed at various barracks at the time of the Army Census were eventually re-formed into one unit; according to Roger McCorley:

“I was sent south to Kerry with a unit which consisted of half Belfast men and half 2nd and 3rd Northern men. We went to Kenmare until March. Then I was fed up. I came back to the Curragh. I wanted to get out of the army or get out of Kerry. The unit then was formed into the 17th Bn., sent to the workhouse in Tralee. Joe Murray, a Belfast man, was in charge of it then.” [50]

There is no suggestion that this unit was involved in any of the atrocities committed by Free State soldiers in Kerry, although news of those events must have contributed to an accelerating sense of disillusion among those men.

Emigration

The nominal rolls provide an additional level of social history in that they allow us to see the extent of IRA emigration from the north between the collapse of the 3rd Northern and the 1930s.

Some of this was involuntary – internees being released were often served with exclusion orders barring them from living in, or even visiting, the north.

IRA internees released in 1923 in Northern Ireland were often served with exclusion orders barring them from living in, or even visiting, the North.

This was the experience of Frank Crummey, one-time Intelligence Officer of the Division. In April 1923, the Free State government appealed for his release, pointing out he had been offered a job at a Dublin school – the RUC City Commissioner for Belfast observed “If this man leaves the Northern area we are better without him”, while the RUC Inspector General declared “It is thought that he ought not to be allowed to be at large in Belfast even for a week.”

At the end of that month, having been served with an order prohibiting him from entering Belfast, Antrim or Down, he was escorted to the border and released.[51]

By the time the nominal rolls were compiled, there were still 2,292 former members of the 3rd Northern Division alive. Of those, 422 or 18% had emigrated. The emigration figures for the Belfast and Antrim Brigades were very slightly below the divisional average – at 17% and 16% respectively. Perhaps surprisingly, in that it had been the least violent Brigade area, a much higher portion of East Down Brigade members had emigrated, 23%.

Within the Brigades, there were some huge differences. In Belfast, A Company of the 2nd Battalion, based in Ardoyne and the ‘Bone, had an emigration rate of only 8%, while for B Company of the 1st Battalion in west Belfast, the figure was 26%. In Antrim, a full third of the entire 4th Battalion had emigrated, while the 1st Battalion of the East Down Brigade had the highest emigration figure of any 3rd Northern unit, at 34%. [52]

Many of those who left, having fought against the creation of the northern state, could not bear to, or felt they would not be let, live peacefully in it. Of course, economic factors and the impact of the Great Depression would have contributed to emigration, as well as political factors, but they do not explain these considerable variances in the emigration rates for different units.

Summary and conclusions

Bearing in mind that the records for some units are either incomplete or non-existent, the material now available shows that the 3rd Northern Division was considerably larger than had previously been thought, with just over 2,400 men who can be identified as members either before, during or after the Truce.

More than its overall size, the most surprising fact is the rate at which the Division expanded after the Truce. As we have seen, the Antrim and East Down Brigades grew enormously, while in Belfast the number of battalions had to be doubled from two to four.

The Northern IRA men suffered disproportionately from unemployment and involuntary emigration after the revolutionary period.

The two new battalions were formed in August 1921, just a month after the Bloody Sunday rioting in Belfast; that summer, the city had seen a second surge in fatalities after the initial outbreak of the pogrom in July 1920.[53] It seems clear that the growth of the IRA in Belfast in the late summer of 1921 was a direct response to the latest increase in sectarian violence in the city.

From July 1920 until October 1922, the risk of violent death was ever-present for nationalists in Belfast. During that period, 280 Catholics were killed in the city, of whom 21 or 8% have so far been identified as members of the IRA. A quarter of the IRA fatalities were victims of the RIC “murder gang”, murdered in their own homes, but three-quarters were killed in action, considerably more than has previously been reported.

The period after the Treaty encompasses the more complicated and contested developments: the split in the IRA, the aftermath of the May 1922 northern offensive and the Civil War in the south.

The bitterness of the divisions over the Treaty were echoed in the split within the 3rd Northern. While up to a third of the Belfast Brigade were listed in the nominal rolls as Executive Forces, the clear majority of 3rd Northern Division as a whole, 81%, remained loyal to GHQ. This “loyalty” was primarily logistical, rather than ideological – they took orders from whichever side in the south could promise the most guns and ammunition for use in the north.

The failure of the northern offensive saw the Division largely decapitated. While Kleinrichert’s assertion that the initial introduction of internment only saw lower-ranking officers captured is correct, within several months, the Executive 3rd Northern had experienced the capture of its O/C and its Quartermaster, Pat Thornbury and Hugh Corvin respectively.

On the pro-GHQ side, the risk of internment was compounded by the flight to the Curragh. In Belfast, of 29 Brigade or Battalion staff officers either before or after the Truce, 3 were interned while 10 joined the Free State Army – in other words, the Brigade lost almost half of its officer cadre. In Antrim, the figures were 3 staff officers interned and 12 in the Free State Army, out of a total of 47 – roughly a third. In East Down, of 38 staff officers, 8 were interned while 4 joined the Free State Army – again, almost a third of its senior officers.

Those officers soon learned that staying in the south was a safer option than returning north, as the northern authorities proved to have long memories – Seamus Woods was interned while on a visit home in November 1923 and was the last prisoner to leave the Argenta.

The outbreak of the Civil War accelerated the breakup of the 3rd Northern Division. By the time the Army Census was conducted, there were 624 men in the Free State Army whose home addresses were in the Division’s area – but only 190 of these can be definitively identified in the MSPC nominal rolls.

The preponderance of men not listed in the nominal rolls suggests that most northern recruits had no prior IRA service before coming south. It appears therefore that the northern units in the Free State Army were mainly composed of inexperienced recruits motivated to enlist for economic or adventurist reasons, built around a small experienced core of pro-GHQ 3rd Northern men.

Apart from the isolated case of Joe McKelvey in the Four Courts, northern IRA participation on the anti-Treaty side in the Civil War was previously thought to mainly involve 2nd Northern Division men who took part in the fighting in Donegal, and Frank Aiken’s 4th Northern Division. However, we now also know that the O/C of the Executive 3rd Northern, along with a small contingent from Belfast, took part in the fighting around O’Connell St in Dublin after the surrender of the Four Courts.

The defeat of the 3rd Northern Division in the War of Independence prompted a level of emigration by its former members far above the general average for the north. In 1911, 1.25 million people lived in the six counties that would go on to become Northern Ireland and it has been calculated that from 1922-38, net migration was roughly 94,000 or 8% of the 1911 population.[54]

However, the rate of emigration by 3rd Northern veterans, whether voluntary or government-imposed, was more than double that, at 18% – and included up to a third of the entire membership of some individual units. It is probably safe to attribute the difference between the 8% rate for the general population and the 18% rate for 3rd Northern veterans to “political emigration” in response to the consolidation of the northern state.

Of those that remained in the north, some continued to be centrally involved in the IRA later in the 1920s and ‘30s. However, the vast majority remembered unfulfilled dreams and broken promises, but above all, learned to endure defeat – in the words of one former officer, “…we in the North found ourselves ‘a lost legion.’” [55]

References

In 1924 the government of the Free State introduced a Military Service Pensions Act, allowing for payment of pensions to men who had served in the IRA for at least three months before the Truce of 1921 and who had served with the National, or Free State, Army during the Civil War. At the same time, an Army Pensions Act offered disability pensions to those who had been wounded, or gratuities to the dependents of those who had been killed. This legislation was extended in 1934 to include anyone who took no part in the Civil War or who had fought on the anti-Treaty side.

To assist the process of assessing claims, Brigade Committees were set up, made up of senior officers from each Brigade of the IRA. One of the tasks they undertook was to compile nominal rolls of the membership of each Brigade, Battalion and Company on two “critical dates”: 11th July 1921, when the Truce began, and 1st July 1922, at the start of the Civil War.

These nominal rolls, and the individual files of thousands of applicants, have been released online by Military Archives since 2012 – these constitute part of its Military Service Pensions Collection (MSPC).

[1] Commander-in-Chief to O/C 3rd Northern Division, 20th October 1922, Mulcahy Papers, UCD Archives Department (UCDAD), P7/B/287

[2] Nominal Rolls, 3rd Northern Division, MSPC, Military Archives, MSPC/RO/401-404, 407-412

[3] Applicants Resident in the Six Counties General File, MSPC, Military Archives, SPG/10; Special Investigation of Six County Cases, MSPC, Military Archives, SPG-10A2 (in November 1926, the extent of over one hundred pension claimants’ pre-Truce service was reviewed by a committee of nine former 3rd Northern Division officers – the application of James Delaney of Balkan St in Belfast was one of those which the committee noted should be rejected, as “This man was a Black & Tan Crossley driver”); Thomas Gunn memoir, ‘Reorganisation in Antrim’, Michael Collins Papers, Military Archives, MA/CP/062/001; 1917-21 Medal recipients, http://mspcsearch.militaryarchives.ie/brief.aspx

[4] D/O Reports – Returns for June and July 1921, Mulcahy Papers, UCDAD, P7/A/23

[5] A Company, based in the Ardoyne and Marrowbone, or ‘Bone, areas; B Company in Ballymacarrett in east Belfast, known today as the Short Strand; C Company in the Markets, just south of the city centre; D Company in the New Lodge in north Belfast. The largest unit was B Company, 1st Battalion, with 179 pre-Truce members; the smallest was D Company, 2nd Battalion, with only 27.

[6] Roger McCorley interview, O’Malley Notebooks, UCDAD, P17b/98

[7] Nominal Rolls, 1st & 2nd Battalions, 1st Brigade, 3rd Northern Division, MSPC, Military Archives, MSPC/RO/403-404

[8] M. McManus to Military Service Pensions Board, 7th January 1937 in 4th Battalion, 1st Brigade, 3rd Northern Division, MSPC, Military Archives, MSPC/RO/406

[9] Nominal Rolls, 1st & 2nd Battalions, 1st Brigade, 3rd Northern Division, MSPC, Military Archives, MSPC/RO/403-404

[10] Roger McCorley statement, Bureau of Military History, Military Archives, WS389

[11] O/C 3rd Northern Division to GHQ, 27th July 1922, Mulcahy Papers, UCDAD, P7/B/77

[12] O/C 3rd Northern Division to GHQ, 21st September 1922, Mulcahy Papers, UCDAD, P7/B/287

[13] Patrick Thornbury, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, Military Archives, MSP34 Ref 07497

[14] Nominal Rolls, 1st Brigade, 3rd Northern Division, MSPC, Military Archives, MSPC/RO/402-406A

[15] Irish Army Census Return dated 12th & 13th November 1922, Portobello Barracks, 2 Eastern Division, Eastern Command, Military Archives

[16] Nominal Rolls, 3rd Brigade, 3rd Northern Division, MSPC, Military Archives, MSPC/RO/412

[17] Denise Kleinrichert, Republican Internment and the Prison Ship Argenta 1922 (Irish Academic Press, 2001), p335-368

[18] Robert Lynch, ‘The People’s Protectors? The Irish Republican Army and the “Belfast Pogrom,” 1920–1922’, Journal of British Studies, Vol. 47, No. 2 (April 2008), p381

[19] Robert Lynch, ‘Belfast’, in John Crowley, Donal Ó Drisceoil, Mike Murphy & John Borgonovo (eds), Atlas of the Irish Revolution (Cork University Press, 2017), p631

[20] James Ledlie, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, Military Archives, 1D325

[21] John Walker, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, Military Archives, 2RB4095

[22] George McCaughey, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, Military Archives, DP8007

[23] William Thornton, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, Military Archives, 1D127; see also Alan Parkinson, Belfast’s Unholy War (Four Courts Press, 2004), p274

[24] Charles McAllister, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, Military Archives, DP6008

[25] James McAllister, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, Military Archives, 2D485

[26] Nominal Rolls, 3rd Battalion, 2nd Brigade, 3rd Northern Division, MSPC, Military Archives, MSPC/RO/410

[27] Kleinrichert, Republican Internment, p21

[28] Ibid, p62

[29] Ibid, p335-368; Nominal Rolls, 3rd Northern Division, MSPC, Military Archives, MSPC/RO/401-412

[30] Notes of interview with Rory Graham, Louis O’Kane Collection, Cardinal Ó Fiaich Library & Archive, LOK IV B.04

[31] File on Patrick Barnes, PRONI, HA/5/2181

[32] Nominal Roll, 1st Brigade HQ, 3rd Northern Division, MSPC, Military Archives, MSPC/RO/402

[33] Nominal Roll, 1st Battalion, 1st Brigade, 3rd Northern Division, MSPC, Military Archives, MSPC/RO/403

[34] Administrative list of Northern County Applicants, MSPC, Military Archives, M/MSP-10

[35] File on Patrick Barnes, PRONI, HA/5/2181

[36] Roger McCorley interview, O’Malley Notebooks, UCDAD, P17b/98

[37] Ernie O’Malley to Liam Lynch, 3rd September 1922, Moss Twomey papers, UCDAD, P69/40

[38] Irish Army Census Return dated 12th & 13th November 1922, 2 & 3 Northern Division, Curragh Command, Military Archives

[39] Irish Army Census Return dated 12th & 13th November 1922, Dundalk, 5 Northern Division, Eastern Command, Military Archives

[40] Irish Army Census Return dated 12th & 13th November 1922, Wellington Barracks, 2 Eastern Division, Eastern Command, Military Archives

[41] Irish Army Census Return dated 12th & 13th November 1922, Beggars Bush Barracks, Dublin Command and ten other barracks, Military Archives

[42] Patrick Thornbury, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, Military Archives, MSP34 Ref 07497

[43] Nominal Roll, Engineering Battalion, 1st Brigade, 3rd Northern Division, MSPC, Military Archives, MSPC/RO/406A; Joseph Billings, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, Military Archives, MSP34 Ref 01089

[44] Ernie O’Malley to Liam Lynch 31st July 1922, quoted in Anne Dolan and Cormac O’Malley (eds), “No Surrender Here!” The Civil War Papers of Ernie O’Malley 1922-24, (Lilliput Press, 2007), p80

[45] Ibid, p556

[46] Robert Lynch, The Northern IRA and the Early Years of Partition 1920–1922 (Irish Academic Press, 2006), p199

[47] Author’s conversation with Pearse McCorley, Felix’s son, 4th April 2013

[48] Irish Independent, 14th December 1922

[49] Email to author from Cathy Gunn, Thomas’ grand-daughter, 14th March 2016

[50] Roger McCorley interview, O’Malley Notebooks, UCDAD, P17b/98

[51] File on Francis Crummey, PRONI, HA/5/1791

[52] Nominal Rolls, 3rd Northern Division, MSPC, Military Archives, MSPC/RO/401-412

[53] Kieran Glennon, From Pogrom to Civil War – Tom Glennon and the Belfast IRA (Mercier Press, 2013), p260

[54] http://www.census.nationalarchives.ie/search/ and http://www.niassembly.gov.uk/globalassets/documents/raise/knowledge_exchange/presentations/series3/trew090114ppt.pdf both accessed 6th May 2018

[55] Joe Murray statement, Bureau of Military History, Military Archives, WS412