‘An invaluable lesson and example to Ireland’ – Grundtvig, the Danish folk movement and Ireland

The influence of the Danish ‘folk high school’ movement in 1930s Ireland. By Barry Sheppard.

The early decades of Irish independence have often been associated with insular cultural nationalism and economic protectionist policies which set the state adrift somewhat from the wider world.

The charge of being insular could also be applied to the Northern Irish state. Despite being part of a Union which still had interests across the globe, it was still very much a parochial society, especially in rural communities.

While there is little doubt that in the main, the focus of the burgeoning Irish Free State was squarely on domestic matters, it is unfair to label it completely adrift of wider international concerns or influences.

The same can also be said of the Northern state, which willingly adapted outside influences, despite its focus on provincial matters. Transnational influences were to be increasingly found in a number of areas of public life on both sides of the Irish border in the first half of the twentieth century, not least when it came to rural matters. This was especially true during the Great Depression of the 1920s and 30s.

The Aftermath of the Crash

Motivated by the effects of high unemployment and a severe lack of opportunities since the economic crash, individuals and organisations across Europe began to look beyond their borders for answers on how to alleviate societal problems in rural communities.

On the island of Ireland a number of individuals who were motivated by promoting rural life, active citizenship, and a means of making a living from the land, came to prominence in both states. Not only this, they actively sought out international examples which could be adapted to suit Irish conditions.

The negative effects of the depression years on rural areas in both the Irish Free State and Northern Ireland were quite similar. In Northern Ireland there were approximately 100,000 small holdings scattered across the state, many farming on a subsistence basis.[1] While in the southern counties there were approximately 258,000 farms, with 230,000 of them under 100 acres and experiencing similar conditions as their northern counterparts.[2]

Across Ireland, poor productivity, and a lack of knowledge in modern farming methods were major factors in the desperate state of the small farms.

Across the island poor productivity, and a lack of knowledge in modern farming methods were major factors in the desperate state of the smaller holdings, with the majority of small farms being classed as ‘uneconomic’. The 1923 Irish Land Act in the Free State attempted to address the ongoing problem of poor productivity by acquisition and redistribution of larger lands. The act, described as an ‘ambitious attempt to solve the land question once and for all’ ultimately stalled.

The slow progress of land acquisition and division soured relations between the electorate and the Cumann na nGaedheal government in the 1920s.[3] While this work significantly increased under Fianna Fáil after 1932, it too slowed considerably after 1936, leading to a notable decrease in support for the party among small farmers in the west.[4]

A decade after the 1923 Land Act, the picture didn’t look good for the many small holdings, with little prospect for any improvement. Areas such as Dunfanaghy in Co Donegal were said to be ‘little removed from the subsistence level’ in 1933. This was the case in many areas down the western seaboard, and in many other parts of the country small holdings were still squeezed by livestock farming, which had almost doubled in size since the mid-nineteenth century.[5]

In Northern Ireland, land reform schemes which had begun under the same acts as those in the south from the late nineteenth century, were being wound down in the early years of the state’s existence by new legislation. A 1925 Land Act saw the compulsory purchase of any remaining tenanted land in Northern Ireland. Under this legislation the remaining 38,500 tenants purchased their holdings until the scheme was finally wound down in 1935.[6]

However, like provisions in the 1923 Land Act, the 1925 Northern Ireland act prohibited the confiscation of untenanted land in certain situations, making precious resources unattainable for some landless people, leaving emigration a more viable option.

One individual who was determined to stem the rural decline, and introduce a new form of adult education to rural dwellers was William Stavely Armour, journalist, educator, and the founder of the rural organisation The Young Farmers Clubs of Ulster. Armour had travelled extensively in the first two decades of the twentieth century seeking out new educational experiences which he would attempt to introduce back home.

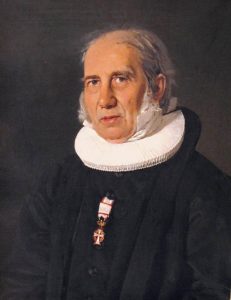

One destination in particular was to have a profound effect upon his efforts, Denmark. It was here he was introduced to the ‘Danish Folk High School Movement’ founded by Bishop Nikolaj Frederik Severin Grundtvig (1783 – 1872).

Grundtvig and the Danish Folk High School movement

Grundtvig was an educational reformer who railed against the established system in his country. He witnessed a system which catered for the elite, and those who could afford a formal university education. A country where Latin had been placed over the mother tongue for centuries.

Grundtvig saw this education system as failing the rural population. While his concerns were wide, he was particularly scathing of the Latin Grammar Schools which, in an echo of Pádraig Pearse’s ‘the Murder Machine’ in Ireland, labelled them ‘The Schools for Death’.[7]

Grundtvig engaged in developing a community education system which worked for the rural population, farmers, and workers in Denmark. His movement by and large represented the interests of the ‘disenfranchised majority’ of nineteenth century Denmark, and ‘sought to build democratic egalitarian societies where none would starve or be forced to emigrate for lack of opportunity or human dignity’.[8]

Grundtvig engaged in developing a community education system which worked for the rural population, farmers, and workers in Denmark

Grundtvig envisaged a community school system with popular education as its primary focus. A movement against the prevailing Danish conservative versions of both education and culture. It was at its heart it was a community movement against the ideals ‘of literacy and book-learning, of language unknown to common people and of learning where the primary relation was between the individual and the book alone’.[9] Discussion alongside national culture would be important factors in generating a rural community spirit which reinvigorated a rural population who had limited resources and opportunities.

This vision was given life in an informal atmosphere where people could temporarily live together, including teachers, and learn from one another in practical agricultural matters and Danish nationalist poetry and culture. It was a place where dialogue would be the tool of instruction, and where no formal tests would be taken. In this ‘school’ a live-in term would last no longer than three or four months. Students would work together on physical enterprise projects, and were encouraged to carry on the dialogue into everyday rural life.[10]

Back on Irish soil Armour became convinced that Grundtvig’s ideas of ‘people’s universities’ could one day be applied to Ireland. Writing in the official history of the Young Farmers Clubs of Ulster in 1978, S. Alexander Blair tells how greatly interested Armour was in this endeavour, and the more he read about Grundtvig himself, the more impressed he became.

‘He (Stavely) agreed with the concept of the Folk High Schools as ‘people’s universities’, and was convinced that the high standard achieved in Danish agriculture resulted from work done in these schools’.[11]

It was said that Grundtvig identified a growing democratic need in society – a need of enlightening the often both uneducated and poor peasantry. This social group had neither the time nor the money to enroll at a university and needed an alternative. The aim of the folk high school was to help people qualify as active and engaged members of society, to give them a movement and the means to change the political situation from below and be a place to meet across social barriers.[12] This philosophy was to be found in the Young Farmers’ Clubs of Ulster motto ‘Better Farmers. Better Countrymen. Better Citizens’.

While Armour’s experiences in Denmark would bear fruit in the foundation of the Young Farmer’s Clubs, he was by no means the only one to see the merits of the organisation. Back in Belfast the Vice-Chancellor of Queen’s University, Dr R.W. Livingstone spoke on the merits of the Danish Folk School model in a speech on education reform at the annual Belfast Royal Academy prize giving ceremony of 1929. The Belfast Newsletter reported that Dr Livingstone stated that the solution to adult education in the province lay with the Danish movement.[13]

‘An invaluable lesson and example to Ireland’

In the early 1930s a series of lectures took place in Northern Ireland on the merits of the movement. In the Ulster Museum and Art Gallery, the Danish movement was debated in a lecture on ‘the most useful parts’ of adult education.[14]

While the aforementioned Dr Livingstone hosted a ‘principal’ of one of the Danish High Schools, Herr Niels Klostergaard in March 1930 for a lecture on the movement.[15]

Even before Stavely implemented Grundtvig’s ideas in Northern Ireland, they had been much debated throughout the island as a way of reinvigorating rural communities. A full decade before Stavely founded the Farmers Clubs, the merits of the movement were debated in Irish newspapers. The Nenagh Guardian in 1919 championed Denmark, and in particular Grundtvig’s ideas as ‘an invaluable lesson and example to Ireland’.

Both north and south of the Irish border, many were impressed with Grundtvig’s ideas.

The Folk Schools’ combination of the principals of agriculture and emphasis on cultural education were a powerful combination to Irish eyes. Indeed the emphasis on the history, literature, songs and folk traditions of its native Denmark was a powerful example for those who had grown up in the Irish cultural revival a few decades previously.[16]

Denmark and Ireland

In terms of agriculture, there have been a number of comparative historical studies of Ireland and Denmark over the years, highlighting the similarities between the two nations. Both were mainly agricultural and competed for the lucrative British agriculture market.

As far back as 1908 the agricultural reformer Horace Plunkett had felt that comparing Ireland to Denmark was good practice for rural reformers.[17] Therefore, it is perhaps unsurprising that others would look to Denmark, when looking for guidance in relation to Irish rural matters.

Away from explicitly agricultural matters there were parallels to be drawn between Ireland and Denmark in terms of cultural nationalism and language revival. Indeed, it is arguable that the two countries had similar traits which saw them as ‘a place apart’ from mainstream European cultural history.

There were many parallels to be drawn between Ireland and Denmark in terms of cultural nationalism and language revival as well as agricultural matters.

It was suggested that Danish cultural history had ‘never quite been woven into the fabric of continental cultural history’. Factors such as the geographic position of Scandinavia in relation to the major continental centres, the small population, and the rural economy contributed to a form of isolation and distinctiveness, which was seized upon as sources of nationalist pride by Grundtvig. [18]

This of course mirrored what happened in Ireland in the late-nineteenth century in terms of cultural revival, especially in Irish-speaking districts. They were almost treated as a place apart by revivalists, ancient and removed from mainstream European and especially British cultural history. For cultural enthusiasts the Danish experience was an example to admire, especially when it came to the prominence they placed on native culture and language. It was stated that Grundtvig was ‘bound up with the idea of a Danish national character’ with a ‘mystic conception of the Danish language as an expression of Volkgeist (national spirit)’.[19]

Cultural nationalism

The nationalist leanings of Grundtvig’s movement found a willing audience in an Ireland fuelled by cultural nationalism which had fed so much into its recent revolutionary period. In 1926 the president of the Gaelic League, Seaghan P. MacEnri would endorse the Danish Folk movement as an example of a vehicle for promoting the native language and pastimes of Ireland. He stated:

“When Ireland was Irish-Speaking and had a practical monopoly of the English food markets, Denmark, with its barren soil, was plunged in poverty. Its upper classes despised their native language and sought “a sound French and German education.” Bishop Grundtvig changed all that when he founded the Danish Folk Schools where farmers’ sons and daughters were taught the language, history and folklore of their own country.

He said that to make good farmers he must first make good Danes, proud of their country and anxious-to promote its prosperity instead of having their eyes continually fixed across the frontier. He succeeded. Foreign influences were eliminated. Danes, from the king to the peasant, became more and more Danish in spirit and language”.[20]

During this same period the Irish Monthly journal would feature a number political figures writing on what the Danish Folk Movement could teach rural Ireland, indicating that intellectual and political circles were seriously taking notice.

This was mirrored on the ground among some farming communities. In 1926 a recommendation to the Co. Council of Mayo to establish a People’s High School for the area ‘on the lines of the Danish folk schools’ was unanimously passed at a conference of representatives of Mayo Co. Council. Co. Technical Committee and Co. Agricultural Committee.[21]

Despite the prevailing notion that those who were either promoting ‘Irish Ireland’, or concentrating on rural matters in Northern Ireland were loath to take on outside influences, there was a desire on both sides of the border to look beyond the island for inspiration in relation to rural reform and adult education.

It is significant that Grundtvig’s ideas would transcend internal borders on the island of Ireland, given that people who may have been diametrically opposed on matters of nationhood found common ground around the Danish bishop’s approach. This resulted in some cross-border cooperation among rural groups at a time when there was very little contact between the two jurisdictions at a state level.

Education

The central need of adult education, incorporating agricultural techniques and community cohesion which Grundtvig advanced in the Folk High Schools was also paramount for Irish rural organisations such as the Young Farmers’ Clubs, Macra na Feirme, and Cannon John Hayes’ organisation, Muintir na Tire.

The Ulster Farmers’ Clubs sought to ‘promote the education and training of young people in agriculture and rural occupations’.[22] They did this in a similar way to the Danish Schools, with instruction being given in, sometimes purpose-built central community halls by an array of teachers and experts.

Macra ne Feirme and the Ulster Farmer’s clubs both sought to ‘promote the education and training of young people in agriculture and rural occupations

Like the Danish Folk Schools, Macra na Feirme also fostered ‘the constant interchange of ideas’.[23] It was noted: ‘As in Denmark with the High Schools, as in Antigonish with the university extension courses, (in Macra na Feirme) the result of education has been a realization of problems and an effort to deal with them’ as many rural problems couldn’t be fixed by legislation or Acts of Parliament.[24]

Armour’s ‘Farmers Clubs’, once they had established their own ‘people’s universities’ would reach out to their southern counterparts Muintir na Tire and Macra na Feirme. In 1942, a delegation from the Young Farmers Clubs of Ulster, headed by Armour’s successor Mr. William Rankin, attended Muintir na Tire’s annual education gathering, ‘Rural Week’ to make connections with like-minded rural organisations, and to promote their own organisation.

At this event it was reported that Rankin ‘was welcomed not as an outsider, even though he was new (to Muintir na Tire)’, and that ‘he brought to (Rural Week) all the drive, vigour, and practical attitude to life of the North-East corner’. Rankin’s personality was said to have left quite the impression on members of Muintir na Tire, as well as the Taoiseach, Eamon de Valera, for whom he sang two comic songs to ‘gales of laughter’ from the assembled attendees.[25]

The benefits of the Farmers’ Clubs was well known to the gathering’s attendees, as a telegram was read from an unnamed ‘influential person’ advising that Muintir na Tire founder, Fr Michael Hayes should follow the lead of the Young Farmers Clubs of Ulster, in that he should begin a Muintir na Tire high school on the lines of the Danish Folk Movement.[26]

This was echoed by Mr Rankin. Writing in the official Rural Week record for that year, he explained the educational approaches of the Young Farmers’ Clubs in Ulster and stated that if ever those in the South were to establish clubs in their jurisdiction they could ‘count on the friendly cooperation and assistance of the Young Farmers’ Clubs of Ulster’.[27] Indeed, this is what happened, with regular educational and social exchanges and trips between Macra na Feirme and the Ulster Clubs right up until the beginning of the Troubles.

The Spread of Ideas

In the immediate years after Rankin’s appearance at ‘Rural Week’ there was a heightened interest in the Young Farmers’ Clubs south of the border. It is unclear if the appearance by the Rankin of the Young Farmers at the 1942 Rural Week had a direct bearing on the farmers clubs which had been forming in various counties, as newspapers and periodicals had discussed the benefits of establishing such organisations since the late 1910s. Nevertheless, action overtook discussion after the Rural Week appearance.

The earliest Farmers Clubs formed in the South in 1942 or 1943, with a small growth over the ‘Emergency’ years.[28] The Munster Express reported in March 1945: ‘A branch of the Young Farmers’ Organisation was formed at a representative meeting held in the City Hall, Waterford, on Wednesday night last, at which Mr. Maurice Murphy presided’.

The transfer of ideas across time and borders show an Ireland at the heart of rural educational reform across Europe and beyond.

The attendance included representatives of another branch of the Young Farmers’ Clubs which had recently been established in the town of Mooncoin, Co. Kilkenny. The report continued: ‘The Chairman said that the meeting had been called for the purpose of organising a Young Farmers’ Club for Waterford and district. The club would be non-political and non-sectarian, (echoing the rules of the Young Farmers Clubs in Ulster) and would be the fourth of its kind established in this country’.[29]

While there was an appetite for this kind of organisation, expansion was slow to begin with, having established competition in Muintir na Tire. The call for Young Farmers’ Clubs would also be made by some of the leading politicians of the day.

In December 1945 Erskine H. Childers TD gave a speech at the Thomas Davis Centenary Celebrations in Athlone, in which he lamented that groups such as Muintir na Tire, successful as they were, had not made an even greater impact in Irish life. He argued that if there were several thousand Young Farmers’ Clubs in England, then why not ten times that amount in agricultural Ireland?[30]

A national executive of Farmers’ Clubs in the South formed in 1944. It has been suggested that the Second World War brought forward the need for Young Farmers’ Clubs in Ireland: ‘The war of 1939-45 highlighted the importance of the agricultural industry in Ireland and the pressing need to move away from the Cinderella image it had developed. In particular it was vital that proper agricultural education should be provided for those young people destined to work the land’.[31]

A report in the latter part of the 1940s argued that the growing organisation of the Young Farmers’ Clubs (Macra na Feirme) were willing to go ‘beyond their own borders in the search for information and truth’. It further stated that representatives of the organisation had gone to England, to Norway, to Denmark; and in turn, had ‘arranged for English, Danish and Norwegian farmers to visit this country’.

The report also emphasised the lengths the organisations had went to in exchanging information, organising lectures and discussions with other bodies, in an effort to further their aims.[32]

This in some ways completed a journey which began midway through the previous century. Grundtvig’s idea of rural education attracted educators like William Stavely Armour to Denmark to learn more about this non-traditional form of education, this in turn spread throughout the island of Ireland, before returning to Northern Europe and Denmark in particular.

The transfer of ideas across time and borders show an Ireland at the heart of rural educational reform across Europe and beyond, and go some way to dispelling the notion that Ireland was a place a part in a modernising Europe.

References

[1] S. Alexander Blair, “Ulster’s Country Youth”: the First Fifty Years of the Young Farmers’ Clubs of Ulster (Belfast, 1979), p. 13.

[2] T. W. Freeman, ‘Emigration and rural Ireland’ in Journal of the Statistical and Social Inquiry Society of Ireland, Vol. XVII, Part 3, (1945/1946), pp 404-422.

[3] Terence Dooley, ‘Land and Politics in Independent Ireland, 1923-48: The Case for Reappraisal’ in Irish Historical Studies, Vol. 34, No. 134 (Nov., 2004), pp. 175-197

[4] Ibid.

[5] Freeman, T. W. ‘Emigration and rural Ireland’. – Dublin: Journal of the Statistical and Social Inquiry Society of Ireland, Vol. XVII, Part 3, 1945/1946, pp404-422

[6] Olwen Perdue ‘Confiscation or regeneration? Land purchase in the North of Ireland 1885 – 1925’

[7] M. Lawson, N.F.S. Grundtvig, in Prospects: the quarterly review of comparative education vol. XXIII, no. 3/4, 1993, p. 613–23.

[8] Rolland G. Paulston (1980) Education as Anti‐structure: non‐formal education in social and ethnic movements, Comparative Education, 16:1, 55-66

[9] A brief history of the folk high school: https://www.danishfolkhighschools.com/about-folk-high-schools/history/

[10] Clay Warren, ‘Andragogy and N. F. S. Grundtvig: A Critical Link’ in Adult Education Quarterly, Vol 39, Issue 4, 1989.

[11] S. Alexander Blair, Ulster’s Country Youth: The First Fifty years of the Young Farmers’ Clubs of Ulster, (Belfast, 1978), p. 18.

[12] A brief history of the folk high school: https://www.danishfolkhighschools.com/about-folk-high-schools/history/

[13] Belfast News Letter, 31 Oct. 1929.

[14] Belfast News Letter, 3 Dec. 1931.

[15] Belfast News Letter, 22 Mar. 1939.

[16] Nenagh Guardian, 27 Sept. 1919.

[17] Cormac Ó Gráda ‘The beginnings of the Irish creamery system, 1880–1914’ in

Economic History Review 30, (May, 1977), pp. 284–305.

[18] E. F. Fain Nationalist Origins of the Folk High School: The Romantic Visions of N.F.S. Grundtvig in British Journal of Educational Studies, Vol. 19, No. 1 (Feb., 1971), pp. 70-90

[19] Ibid

[20] Meath Chronicle, 2 Jan. 1926.

[21] Irish Independent, 9 Jun. 1926.

[22] (P.R.O.N.I., Young Farmers’ Clubs of Ulster Reports 1943-1946, ED/13/1/2121)

[23] Louis P. F. Smith, The Role of Farmers Organizations in An Irish Quarterly Review, Vol. 44, No. 173 (Spring, 1955), pp. 49-56

[24] Ibid

[25] Irish Independent, 21 Aug. 1942.

[26] Irish Independent, 21 Aug. 1942.

[27] ‘MNT Rural Week Record 1942’ (Printed by the Limerick Leader, Limited) p 98.

[28] Michael Shiel, The Quiet Revolution: The Electrification of Rural Ireland 1946-76 (Dublin, 2003), p.183.

[29] Munster Express, 16 Mar. 1945.

[30] Longford Leader, 22 Dec. 1945.

[31] M. Shiel, The Quiet Revolution, p. 182.

[32] Kilkenny People, 17 Dec. 1949.