Ireland and the First World War – A Brief Overview

By John Dorney

Ireland throughout the First World War of 1914-1918 was an integral part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. But its experience of the Great War was quite different from that of England, Scotland or Wales.

In Ireland, engagement with the war was less and casualties were lighter, but the war was also much more divisive and ultimately helped to speed Ireland’s secession from the United Kingdom.

From Home Rule to Great War

When the War broke out in August 1914, Ireland was in the midst of a serious constitutional and political crisis. Home Rule or Irish self government was promised by the Liberal government, as part of a deal with the Irish Parliamentary Party, since 1912. However, Ulster Unionists, led by Edward Carson and James Craig, mobilised against Home Rule, forming their own militia the Ulster Volunteer Force.

Nationalists responded by forming the rival Irish Volunteers, and over the next two years, both sides imported weapons in significant quantities. It appeared by the summer of 1914, as if Ireland could be bound for civil war.However the Home Rule crisis was interrupted by a greater one.

When the War broke out in August 1914, Ireland was in the midst of a serious constitutional and political crisis.

At this point, war broke out in Europe, when after the assassination of Austro-Hungarian Archduke Franz Ferdinand by a Serb nationalist, Austria-Hungary, supported by Germany declared war on Serbia. Russia mobilised in defence of its ally Serbia and Germany, fearing a two front war with Russia and its western ally France, in pre-emptive attack, invaded Belgium, Luxembourg and France.

Britain declared war on Germany and its allies on August 4, 1914, ostensibly in protest at the Germans’ violation of neutral Belgium’s sovereignty.

In Ireland, Britain’s declaration of war temporarily eased tensions. Both unionist leader Carson and nationalist leader John Redmond declared their support for the war effort and Home Rule was suspended for the duration of the war. Redmond even took the unprecedented step for an Irish nationalist leader of calling for the Irish Volunteers to join the British armed forces at a speech in Woodenbridge County Wicklow in September 1914.

Redmond’s motives were in part political, as he needed the support of the government of Herbert Asquith for Home Rule to pass. He also hoped that Irish volunteers in the British Army could return as an Irish Army under Home Rule and that service in the war could ease animosity between nationalist and unionists. But many Irish nationalists, including members of Redmond’s party such as Tom Kettle, were also genuinely outraged at the German invasion of Belgium and especially atrocities such as the sack of Louven.

John Redmond’s support for the British war effort caused a split in the Irish Volunteers, but the vast majority, in a ratio of about 10-1, followed Redmond into a new organization, the National Volunteers.

The smaller more militant group about 10,000 strong, kept the name Irish Volunteers and a secret group within them, led by members of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, planned an insurrection against British rule before the war was over. They eventually launched their uprising at Easter 1916.

Recruitment

A total of 206,000 Irishmen served in the British forces during the war. The recruitment rate was highest in Ulster, which was as high as in Britain itself, Leinster and Munster were about two thirds of the British rate of recruitment before conscription, while Connacht lagged behind them.

Of those Irishmen who served in British forces in the war; 58,000 were already enlisted in the British Regular Army or Navy before the war broke out.

Of the 140,000 men who were volunteers recruited for the duration of the war, only 24,000 originated from the Redmondite National Volunteers and 26,000 from the loyalist Ulster Volunteers. See here.

Of the 140,000 men who were volunteers recruited for the duration of the war, only 24,000 originated from the Redmondite National Volunteers and 26,000 from the loyalist Ulster Volunteers. See here.

Motivations for joining up varied widely. Some unionists, both north and south, were motivated by loyalty to Crown and Empire. And recruitment was indeed highest in the unionist stronghold of northeast Ulster.

Some Redmondite nationalists also believed they were fighting for a good cause, for Home Rule and ‘in defence of small nations’ against ‘German militarism’.

Over 200,000 Irishmen and some women served in the war.

But recruitment was also fairly strong in traditional recruitment grounds such as Dublin, Cork and Tipperary, where there was a long and apolitical tradition of service in the British military. Inducements such as ‘separation money’ paid to the families of serving soldiers were also attractive to unemployed or lowly paid workers.

Irish separatists who opposed the war, labelled those who had family in the armed forces and were usually hostile to the republicans, as ‘separation women’, due to their receipt of the separation allowance; the implication being that their loyalty had been bought.

Mass voluntary recruitment however, was mainly a feature of the first two years of the war. While 44,000 Irishmen enlisted in 1914 and 45,000 followed in 1915, this fell to 19,000 in 1916 and 14,000 in 1917 and between 11 and 15,000 in 1918.

In short, military service became less popular as the war went on and casualties mounted.

Compulsory military service or conscription was not imposed on Ireland in February 1916 when it was enacted in the rest of the United Kingdom and it was not until April 1918 that an attempt was made to extend it to Ireland.

While recruitment was less than in Britain itself, it still represented a huge mobilization of Irish manpower – roughly one in every three of military aged males in Ireland served in British forces during the war.

Irishmen served throughout the British armed forces, but wartime recruits were primarily organised in three Irish Divisions, the northern based, and Unionist inclined, 36th Ulster Division, and two southern Divisions the 10th and 16th Irish. Of the three, the latter, the 16th Irish, had the strongest influence from Redmondite nationalists.

At the fronts

Irish regular soldiers were engaged from the start of the war in the British Expeditionary Force in France and Belgium, taking heavy losses in 1914, as did all of the pre-war professional British Army.

In 1915, the 10th Irish Division, including the Dublin and Munster Fusiliers and other Irish regiments, were sent to the Dardanelles, in an attempt to knock Turkey out of the war.

They took very heavy casualties in the ensuing Gallipoli campaign, many of them new wartime volunteers, as opposed to pre-war professional soldiers. The heavy losses during the unsuccessful campaign at Gallipoli impacted heavily on Ireland and contributed to the subsequent decline in recruitment.

The 10th Division was then sent to Salonika in northern Greece to fight against the Bulgarians, and later in 1917 to Palestine to again fight the Ottoman Turks. In 1918 some parts of its were redeployed to the Western Front.

The 16th Division, after a period of training in England, was sent to the Western Front at Loos in France in the spring of 1916. There, coincidentally at the same time as the Easter rebellion was raging in Dublin, it suffered heavily in a German gas attack in April 1916.

Irish units were engaged on many fronts from Belgium and France to Salonika and Gallipoli to Palestine. They suffered heavy losses.

Both the 16th Irish and 36th Ulster Divisions participated in the huge British offensive at the Somme from July to December 1916. While both divisions performed well and took their allotted objectives, they both took massive losses in the battle.The two Divisions actually served beside each other in the battle of Passchendale in 1917, another costly and inconclusive offensive.

Among the dead at the Somme was nationalist Member of Parliament Tom Kettle. Another MP, Willie Redmond, brother of Home Rule Party leader John, was killed in the battle of Messines the following year.

One of the effects of the heavy casualties of 1916-17 as well as sluggish recruitment in Ireland itself, was that the Irish Divisions began to lose their distinctive Irish character as losses were often replaced with new recruits or conscripts from England. By 1918 the Irish Divisions were still in the field and participated in the great battles of that year, the German Spring Offensive and the allied counter attack late in the year, but by that time contained many men and units from outside of Ireland.

Meanwhile at home, the war had some contradictory economic effects. Irish farmers prospered as Britain’s overseas markets for food and animals were temporarily cut off by the war and the German u-boat campaign. However the intensive export of food from Ireland created great hardship among the urban poor as it pushed up the price of food. A handful of armaments factories were located in Ireland, but by and large Ireland did not benefit greatly from participation in the war industry.

Opposition to Conscription

By 1918, popular support for the war had ebbed in Ireland. As well as the heavy losses suffered by Irish units, the British government had to face political problems.

Its heavy handed suppression of the separatist armed rebellion in Dublin in April 1916 and especially its execution of the leading insurrectionists and wholesale arrest of radical nationalists was extremely unpopular.

The growing confidence of the separatists was boosted by the British government’s decision, after initially imposing heavy penal sentences, to release all the prisoners taken after the Rising in late 1916 and early 1917.

Another prominent republican, Thomas Ashe, arrested under wartime Defence of the Realm legislation, died on hunger strike in 1917.

In 1918 an attempt to impose conscription sparked off mass resistance in Ireland.

The separatists recorganised in the political party Sinn Fein and, explicitly campaigning against recruitment, the war and for Irish Independence, began to win by-elections. Most poignantly, Eamon de Valera took the seat vacated by Willie Redmond in County Clare, who was killed serving in the British Army at the front.

Secondly, Home Rule which had been promised since 1912 had never become a reality, despite attempts to revive negotiations in 1916 and at the Irish Convention of 1917, overseen by the new Prime Minister David Lloyd George. Unionist by this time were insisting on partition of north east Ulster fro the rest of Ireland in the event of Home Rule coming into force.

All of these factors meant that by the time conscription was extended to Ireland in April 1918 – at a time when British forces were under severe pressure during the German Spring Offensive – most Irish nationalists were united against it.

The anti-conscription campaign brought together Sinn Fein, the Irish Parliamentary Party (which in 1914 had encouraged recruitment) led by John Dillon, the Catholic Church and the trade union movement – who called a one day general strike in protest. Faced with mass mobilisation against conscription and possible armed resistance by the rejuvenated Irish Volunteers, the British government backed down and conscription was never implemented in Ireland.

Just after the war ended, in December 1918, Sinn Fein resoundingly won the general election in Ireland, taking 73 out of 105 seats. In January 1919 they declared independence. Thus the Great War, which John Redmond, who died in early 1918, hoped would make a Home Rule Ireland a contented part of the United Kingdom, actually hastened a rupture between Ireland and Britain.

Casualties and memory

In all, the First World War cost the British Empire over 1.1 million lives, of which about 880,000 were soldiers from Britain and Ireland. Another 2 million were wounded.

Irish casualties are recorded in the Irish War memorial at Islandbridge in Dublin as over 49,000 killed in the war.

However, this refers to deaths in Irish units, which also included soldiers from outside of Ireland. The British registrar general recorded 27,405 deaths among those soldiers born in Ireland in Irish units.

This total however appears to be too low as Irishmen also served in other units of the British armed forces.

At least 37,000 Irish soldiers lost their lives in the First World War.

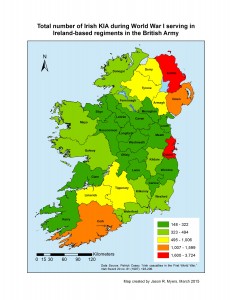

Recent research, for instance here by Jason Myers, has found at least 37,091 fatal Irish casualties. North east Ulster was the hardest hit, followed by Dublin and Cork, while the rural midland counties were the least affected.

To this death toll should be added, in terms of the impact of the war on Irish society, another 20,000 deaths in Ireland due to the great flu epidemic of 1918-19, which was in an indirect by-product of the Great War.

The War remains a much debated topic in Ireland. For Ulster unionists it represented a great sacrifice on behalf of Britain, earning them the right to opt out of Irish self government.

For nationalists, participation in the war was largely seen as a mistake following Independence in 1922 and superseded in popular memory by the struggle for Independence from 1916 to 1921. However, there were popular commemorations by Irish veterans up to the 1940s and the Irish Free State paid for the national war memorial in Dublin.

In recent decades, many have sought to rehabilitate the reputation of John Redmond and those who volunteered to serve on Britain’s side in the Great War of 1914-18.