Today in Irish History, December 14, 1918 – The General Election of 1918

The historic victory of Sinn Fein. By John Dorney

No election in Irish history has been as decisive as the British General Election of 1918. From this election comes the roots of the modern Irish state, but also of modern Irish Republicanism and its claim for a mandate for the full independence of all Ireland.

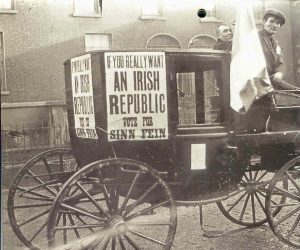

On December 14 1918, only a month after the end of the Great War, the United Kingdom held its first ever general election with almost universal adult suffrage – every man over 21 and most women over 30 were entitled to vote. Sinn Fein – running on a promise to withdraw from the British parliament and set up a rival Irish one, secured a historic and unprecedented victory. The separatists won 73 seats out of 105 and just under 55% of the vote in contested seats.[1]

Sinn Fein’s manifesto was very clear. Their policy was not Home Rule but separation from Britain and the formation of an Irish Republic.

Sinn Fein’s manifesto was very clear. Their policy was not Home Rule, or self-government within the United Kingdom, but separation from Britain and the formation of an Irish Republic. They declared they would secure independence;

-

By withdrawing the Irish Representation from the British Parliament, and by denying the right and opposing the will of the British government or any other foreign government to legislate for Ireland.

-

By making use of any and every means available to render impotent the power of England to hold Ireland in subjection by military force or otherwise.[2]

Their initial strategy was to appeal to the great powers at the Paris Peace Conference for the right to self-determination. But the vote for Sinn Fein, the party associated with the military group the Irish Volunteers and with the Rising of 1916, had revolutionary implications. In January 1919 they declared independence and set up their own parliament in Dublin; the First Dáil. The stage was set for a bloody three year confrontation with the British government.

The rise of Sinn Fein

The victory for Sinn Fein would have been unthinkable prior to 1914, when it had been a marginal party. Arthur Griffith had founded the party in 1905 on the basis of abstention from the British parliament and formation of an Irish one under a ‘dual monarchy’, where Ireland would be an equal partner in the United Kingdom. Griffith argued at the time against purist Republicans that ‘the mass of people were not separatists and would not actively support a rigidly separatist policy’.[3]

The victory for Sinn Fein would have been unthinkable prior to 1914, when it had been a marginal party. Arthur Griffith had founded the party in 1905 on the basis of abstention from the British parliament and formation of an Irish one under a ‘dual monarchy’, where Ireland would be an equal partner in the United Kingdom. Griffith argued at the time against purist Republicans that ‘the mass of people were not separatists and would not actively support a rigidly separatist policy’.[3]

But after the Easter Rising of 1916, veterans of the insurrection, after their release from prison in 1917, had effectively taken over the party and combined Griffith’s policy of abstentionism with the pursuit of a fully independent Irish Republic.

The party won a string of by-elections in 1917, notably Eamon de Valera, the new President of Sinn Fein, in County Clare, defeating the previously dominant Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) led by John Redmond. The Irish electorate was angered by the repression of the 1916 Rising, especially the execution of its leaders, and by the continued hardship brought on by the Great War. Moderate nationalism been discredited by its support for the British war effort and by continued postponement of Home Rule, which it had expected to get in return and which in theory had been enacted in 1914. The Redmondites’ popularity was further damaged by the prospect of the partition of Ireland, due to Ulster unionist resistance to Home Rule.

The IPP’s failure to achieve Home Rule, support for the British war effort and the fallout from the Easter Rising hollowed out support for the Irish Parliamentary Party.

But what finally crippled the IPP was the conscription crisis of 1918. In April of that year, Lloyd George the Prime Minister had attempted to extend conscription for the Great War to Ireland. The IPP withdrew from parliament in protest, implicitly admitting that Sinn Fein’s position, that working through the British parliament was a waste of time, was the correct one.

Meanwhile Sinn Fein led the anti-conscription movement, which consisted of mass rallies, a general strike by the Trade Union Congress and threatened armed resistance by the Irish Volunteers. It was they, the separatists, who claimed the credit in the end for staving off conscription.

In May of 1918, the British government arrested and interned over 70 Sinn Fein leaders, including Eamon de Valera and Arthur Griffith, alleging a ‘German Plot’ between the separatists and Britain’s enemies abroad. Further arrests, followed.

For instance, Robert Brennan the Sinn Fein director of elections was arrested and imprisoned three weeks before polling day.[4] Two Sinn Fein prisoners, Richard Coleman and Pierce McCann, died of illness, casualties of the Spanish flu epidemic during their imprisonment in 1918.

Elected unopposed

John Dillon the leader of the IPP since the death of John Redmond in early 1918, declared that his party would ‘fight the election with all the resources at their disposal’.

However, in many constituencies, the Irish Parliamentary Party did not even field candidates. In County Cavan, for instance, Sinn Fein’s Peter Paul Galligan, was elected unopposed for West Cavan, as was Arthur Griffith in East Cavan (who had earlier in the year, been elected there in a by-election). Both Galligan and Griffith incidentally, were interned in Reading Jail, at the time, for the ‘German Plot.’

Ernest Blythe was returned for Monaghan alongside Eoin O’Duffy, who was likewise in prison for holding a rally with hurling sticks during the conscription crisis. Similarly, the imprisoned Eamon de Valera was returned unopposed for East Clare as was Michael Collins (who had escaped the round ups) for Cork South.

In West Kerry, the IPP candidate, Tom O’Donnell, withdrew to wait for the “whirlwind of political insanity” to pass. Of Sinn Fein, he said, “I think the Sinn Fein policy, devoid of reason and sanity, has ruined and will further ruin my country…the storm will pass, leaving the stable, honest Irishman untouched”[5]. His seat was taken by Austin Stack of Sinn Fein.

Twenty seven out of 105 constituencies were uncontested in 1918, but 64 out of 103 were uncontested in the election of 1910.

The fact that so many Sinn Fein candidates were unopposed seems to modern eyes to partially discredit their victory in 1918, but in fact it had been the most democratic election in Irish history to date. In 1910, the last general election, 64 out of 103 constituencies were uncontested, compared to 27 out of 105 in 1918.[6]

Under the new franchise the electorate was almost tripled, from 700,000 men to just under two million men and women, and in contested constituencies there was a turnout of around 68%. In 1910, by contrast, the last election that the IPP dominated, there were a total of only 207,000 votes cast in Ireland, all men, or fewer than one third of those eligible to vote. [7] It is often noted that 1918 was the first time that women could vote in a general election in Ireland (or in the UK), but what is not as often recognised is that 1918 was also the first time most adult Irishmen had the opportunity to use their franchise.[8]

It has been debated whether the new voters were decisive in the swing towards Sinn Fein, but certainly Republican observers at the time thought the younger voters and newly enfranchised women were voting for their party.

The election was still different from what we would expect today however. A strange feature of it, to modern eyes, was that a single candidate could run for and hold, more than one seat. De Valera for instance ran for the Falls Division Belfast and East Mayo as well as the Clare constituency and was elected in the latter two. [9]

The newly formed Irish Labour Party and also the All For Ireland League (a pre-war split from the IPP) stood aside for Sinn Fein in order for the election to be a straightforward exercise in self-determination.

In the north, the nationalist parties Sinn Fein and the IPP, in an electoral deal brokered by Catholic Cardinal Logue, divided the seats between them so as not to let the Unionists in. According to Dorothy Macardle the Sinn Fein executive had not wanted the deal, but Eoin MacNeill agreed to it on their behalf.

The Cardinal allocated Derry city, East Down South Fermanagh and South Tyrone to Sinn Fein and South Down, East Donegal, East Tyrone and South Armagh to the IPP.[10]

In Belfast Falls Division, where Eamon de Valera faced off against populist IPP nationalist Joe Devlin, it was ‘Wee Joe’ who triumphed among nationalist voters. Winnifred Carney, another Rising veteran, socialist and former secretary to James Connolly was given the unenviable task of standing for Sinn Fein in unionist east Belfast. She won only 500 out of nearly 20,000 votes.

Independent labour candidate in Belfast picked up a respectable number of votes: of between 20-25% in three constituencies, but had no candidates elected.[11]

Overall, though, Ulster remained a fortress for unionism. Unionists in the nine Ulster counties won more than twice as many votes as Sinn Fein (234,376 to 110,032), and in the six counties that would later make up Northern Ireland, the unionist majority was still larger. [12]

Street fighting

In some places, the election battle was a literal as well as metaphorical fight. In Dublin there was major disorder between Republicans and pro-British crowds, especially around the Armistice of November 11, 1918 that ended the First World War, but the December 1918 election passed off relatively peacefully.

In some places, the election battle was a literal as well as metaphorical fight. In Dublin there was major disorder between Republicans and pro-British crowds, especially around the Armistice of November 11, 1918 that ended the First World War, but the December 1918 election passed off relatively peacefully.

Oddly violence was worst not between nationalists and unionists but between rival nationalists of Sinn Fein and the IPP.

The Irish Volunteers provided security and stewards for Sinn Fein, while members of the Ancient Order of Hibernians, which was affiliated with the IPP, often acted as that party’s strong arm organisation. Also generally hostile to the Republicans were many Irish ex British Army servicemen and their wives, the ‘separation women’ .

In Waterford city, where the IPP candidate William Redmond held onto the Party’s seat, a republican activist reported; “Redmondite mobs, mainly composed of ex-British soldiers and their wives…carried on in a most blackguardly fashion, Anybody connected with Sinn Fein was brutally assaulted with sticks, bottles etc.”.[13]

In County Clare, according to one republican’s memory, the ex-British soldiers were, “like lunatics, attacking with knives and heavy sticks”. Shots were also fired at Sinn Fein election workers. In the north, for instance in West Belfast, Tyrone and South Armagh, many activists remembered vicious brawls between the Volunteers and the local Hibernians. [14]

In many areas, Sinn Feiners and the Irish Volunteers clashed with Home Rulers and Hibernians in the streets.

Both Republicans and Redmondites used impersonation and intimidation. In Cork city, one of the successful Sinn Fein candidates Liam de Roiste thought that the IPP impersonated in the morning and the Sinn Feiners followed suit in the afternoon. ‘I am sorry to say’, he wrote, ‘that it is looked upon in the light of a good joke.’[15]

Street fighting and trickery had long been a staple of Irish elections, however, and was certainly not something Sinn Fein brought to bear for the first time in 1918. In Cork city for instance, 11 eleven people had been shot, two fatally, in elections in 1910, in confrontations between the rival nationalists of the Irish Party and the All For Ireland League. Electoral violence in 1918, by comparison, was fairly restrained. [16].

The Irish Volunteers and Sinn Fein in 1918 certainly gave as good as they got in brawls with Hibernians and ex-servicemen, but street violence was no worse than usual at election time and was not the reason for their victory as has sometimes been claimed. Sinn Fein were also the only party whose leaders and activists were being arrested and jailed in large numbers in 1918.

In Cork city, JJ Walsh and Liam de Roiste won over 66% of the vote each to take the two seats in that city.[17]

In the capital, Dublin, out of nine contested seats, Sinn Fein won eight. Richard Mulcahy the Volunteers’ Chief of Staff was elected in Clontarf on the north side of the city. Sean T O’Kelly trounced his Irish Parliamentary Party rival in College Green.

In the capital, Dublin, out of nine contested seats, Sinn Fein won eight. Richard Mulcahy the Volunteers’ Chief of Staff was elected in Clontarf on the north side of the city. Sean T O’Kelly trounced his Irish Parliamentary Party rival in College Green.

Among the other Republican MPs in Dublin were Easter Rising veterans Constance Markievicz (the first ever woman MP to be elected to the British Parliament), Desmond Fitzgerald and Joe McGrath.

Out of about 140,000 votes in the city, Sinn Fein had received 79,000 or about 60% of the vote. The remaining contested seat in Dublin was won by Unionist Candidate, Maurice Dockrell in Rathmines and two more unionists were elected unopposed for Trinity College Dublin, the only unionist elected outside of Ulster. [18] There was also a strong working class vote for Alfie Byrne a populist, though anti-conscription, IPP candidate in the Harbour constituency of Dublin, though he failed to get elected.[19]

It would be naïve to imagine that all those who opposed the ‘Sinn Feiners’ throughout the war years and before came over to their side in 1918. But there was no doubt that, at least outside of north east Ulster, Sinn Fein had a mandate to pursue Irish independence. Whether that would entail political bargaining, mass protest or armed resistance was still uncertain in December 1918.

But on January 21 1919, the Sinn Fein MPs met in Dublin’s Mansion House and declared Irish independence. It could reasonably be said that all of subsequent twentieth century Irish history flowed from the votes cast on December 14, 1918.

If you enjoy the Irish Story and wish to support our work, please consider contributing at our Patreon page here.

References

[1]Michael Laffan, The Resurrection of Ireland: The Sinn Féin Party, 1916-1923, p. 164, Sinn Fein’s total vote was about 46% of the electorate but many of the uncontested seats had also been won by the party in by-elections in the previous two years. It is posited that Sinn Fein’s true support was closer to 66% of the electorate.

[2] Dorothy MacCardle, The Irish Republic, p.244

[3] PS O’Hegarty, The Victory of Sinn Fein, p.21

[4] MacCardle, p.237, 245

[5] T Ryle Dwyer, Tans Terror and Troubles, p. 152-153

[6] Charles H. E. Philpin, Nationalism and Popular Protest in Ireland p.415

[7] http://www.ark.ac.uk/elections/h1918.htm Marie Coleman (The Irish Revolution 1916-1923) cites 698,000 eligible voters in 1910 and 1.93 million in 1918.

[8] In 1911 the population of all Ireland was 4.3 million. 700,000 is roughly 16% of 4.3 million. If half the population was female then roughly 32% of all males had the vote in 1910. But if we include only adult males then it would be somewhat higher. According to the 1911 census, roughly 40 % of the population was under 21. Which means that about 50% or so of males over 21 had the right to vote in 1910. In 1918, there were 1.93 million voters and a turnout of 68%. (Here http://www.ark.ac.uk/elections/h1918.htm)

[9] MacCardle p.245-246

[10] Ibid. Though in East Down the pact between Sinn Fein and the IPP broke down, meaning that unionists won the seat despite the nationalist parties between them getting more votes. My thanks to Cathal Brennan for this information.

[11] Conor Kostick, Revolution in Ireland, Popular Militancy 1917-1923, p.49

[12] Marie Coleman, A Divided Ireland, Unionists and the Election of 1918, https://www.rte.ie/eile/election-1918/2018/1207/1015896-a-divided-ireland-ulster-unionism-and-the-1918-election/

[13]Annie Ryan, Comrades, Inside the War of Independence, p222.

[14] For Clare, Padraig Og O Ruairc, Blood on the Banner, p.63, For the north See for instance John McCoy BMH WS402 and Kevin O’Shiel BMH WS 1770. Though the worst rioting between republicans and Hibernians took place in the by-elections of early 1918 in South Armagh and East Tyrone rather than in the general election of December, by which time Cardinal Logue had brokered a deal between the rival nationalists in Ulster.

[15] John Borgonovo, The Dynamics of War and Revolution, Cork city 1916-18, p.227

[16] Peter Hart, The IRA and its Enemies, p.47

[17] Borgonovo, Dynamics of War and Revolution, p.228

[18]or the results see www.irishelections.org

[19] Alfie Byrne re-took seat as an independent 1922 and later served as Lord Mayor of the city. The results in the Dublin constituencies can be viewed here http://electionsireland.org/results/general/01dail.cfm