The Riddle of Ross Island: Ireland’s enigmatic early miners

How did a copper mine in prehistoric Ireland seemingly emerge from nowhere? By Patrick Fresne.

Nearly four and a half millennia ago, Ireland jumped from the stone-age to the metal-age in less than two centuries.[1]

The dawn of the metal-working era heralded a golden age in Ireland, and the transition could justifiably be described as a shift from stone-age to a gold-age, for some of the earliest metal worked objects in Ireland are of gold.

The primary metal of industry in the era was initially arsenical-copper, and later shifted to bronze, but gold metalworking remained a constant feature over this period. Ancient Ireland stands out in this regard, with more Bronze-Age ornaments of gold having been discovered in Ireland than in any other Western European country.[2]

Four and a half millennia ago, Ireland jumped from the stone-age to the metal-age in less than two centuries.

It was the ancient red metal, copper, that appears to have first caught the attention of the first mineral prospectors in Ireland. The earliest copper production in Ireland, associated with the ancient mine at Ross Island in the south-west of the province of Munster, is generally considered to have commenced operations around 2400 BCE,[3] and south-western Ireland had become a major centre of copper production by 2200 BCE.

The pioneering copper-miners in the island appear to have exhibited an impressive level of expertise, seemingly capable of identifying the most promising copper deposits, washing and concentrating the ore, and controlling the roasting and smelting process in a competent manner.[4]

The copper ore unearthed at the site was naturally rich in arsenic, which may have acted to strengthen the end-product, raising the possibility that these pioneers were capable of identifying this signature characteristic of the local ore.

This high level of expertise, as well as the speed of the transition from stone to metal, suggests that outsider influence had no small hand to play in the development of the metal industry in ancient Ireland, as there is little evidence for copper-working in Ireland’s Neolithic societies.[5]

Where did these expert miners come from?. There were no copper mines operating in Britain at this time [6], and so Ireland’s closest neighbour can be ruled out as a source for the early copper production activity. This leaves only two other regions as serious contenders: Iberia and the land that is today known as France.

Historians seem to sit on the fence regarding the question of origins of the Ross Island miners,[7] and this reticence to point to a destination of origin might reflect something of a wince to the old legends tracing the origins of the Irish to Iberia, a view which has long been out of vogue.

That said, the case for an Iberian origin for the first miners at Ross Island is quite strong, and the evidence in support of this argument will be outlined below using a variety of sources from the fields of history and geology.

There is also a possibility that the first miners in Ireland might have been listed among the groups of ancient ‘invaders’ of Ireland outlined in an early Irish chronicle, the Lebor Gabala Erenn.

The Operations of a Prehistoric Copper Mine

Almost all the earliest surviving copper artefacts in Ireland have a distinctive arsenical composition, the main source of which can be traced to a mine in south-west Ireland, located at Ross Island in County Kerry.

The Ross Island mine was the first major copper mine in north-western Europe, and most of the earliest copper objects in Ireland, and many in Britain, appear to have been fabricated from copper sourced from the Ross Island Mine.[8]

Ross Island is a peninsula that juts into Lough Leane, the largest of the Killarney lakes. The mine was excavated in the 1990s, but the exact depth of the mine is not really known, as the shafts are flooded and were damaged by mining in the area that was undertaken in recent centuries.[9]

The Ross Island mine was the first major copper mine in north-western Europe

Viewed through modern eyes, the work-tools used at the site appear to be crude and rudimentary: shovels made from cattle-bones and hammers made from stone cobbles. Having to rely on such primeval instruments to break through the rock-face, the miners adapted a specialised technique called fire-setting to work around the limitations of their tools.

The technique of fire setting involved piling up combustible wood against the rock to build up a wood-fuelled fire, after which the fractured rock would be pummelled by stone hammers. Wooden wedges could also have been inserted into the cracks that formed as a result of the high temperatures, allowing slabs of rock to be prised out.[10]

The immediate access to water was probably one feature of the site that attracted Ireland’s pioneering miners to Ross Island. The fires could be swiftly extinguished with water from the lake, speeding up the progress of work, and it is possible that the nearby water was also employed to wash the ore, separating the crushed ore from the heavier metals.

Initially, the mining activity at Ross seems to have been carried out on a seasonal basis, with one authority suggesting that work was carried out during the colder, winter months.[11]

The acidic soils of the sandstone mountainsides adjacent to the Lough is an ideal environment for oak-trees, and forests of oak in the area might have also caught the eye of the first miners. The dense wood of the oak-tree would have been an ideal fuel for building up the high-temperature fires to induce thermal-stress in the rock. It is possible that ancient prospectors may have taken cues from the flora in an area: one very productive ancient mine in the Rio Tinto region of Iberia, the Cerro Salomon, seems to also have been once surrounded by oak forests.[12]

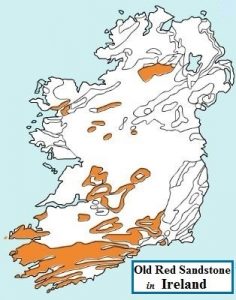

The primary feature that would have attracted the first hopeful miners to the area, however, would have been evident in the mountains and valleys of the region, which are formed of two types of rock, the first, known as Carboniferous Limestone, and the second, Old Red Sandstone. Both these types of rock, and especially the latter, are considered to be prospective for copper.

Old Red Sandstone

‘There is a lake called Lough Lein. Four circles are around it. In the first circle, it is surrounded by tin, in the second by lead, in the third by iron and in the fourth by copper…’

-Nennius, c. 829 AD [13]

The Early Medieval work, Historia Brittonum, generally considered to have been compiled by the 9th Century Welsh monk Nennius, ends with a sort of addendum which lists the wonders to be found in the Islands of Britain and Ireland.

The remarkable geology of the Lough Leane area is one of only two wonders on this list that are to be found in Ireland. It is curious that even as late the Early Christian era, the area around Ross Island was still associated with the mining of useful metals. It is worth asking the question as to why it was that the earliest copper-age mines in Ireland are found in the South-west of the island?.

The most obvious reason rests on the geology of the area: the dominant rock in the south of the province of Munster is a Devonian-aged type known as ‘Old Red Sandstone’.

As late the Early Christian era, the area around Ross Island was still associated with the mining of useful metals

This variety of rock is frequently associated with copper, and in Ireland, it is particularly common in the province of Munster, where it is found in every county, and especially so in the south-west of the province, where it forms the dominant bedrock.

This characteristic of the Munster geology would have likely imparted a considerable strategic significance to the province in an era when every smithy’s workshop would have had a voracious appetite for the red metal.

A mass of this ‘Old Red Sandstone’ runs alongside the southern bank of Lough Leane, but the base of the valley in which the lake sits is formed of another type of rock called Carboniferous Limestone.

The Lough thus sits on the junction of two great rock formations. Areas with this kind of overlapping geology are generally considered to be prospective for minerals, a feature that may have caught the attention of ancient prospectors. Limestone is also an easier rock to work than is sandstone, another important consideration in an age when miners’ hammers were made of stone and their picks of animal-horn.

The highest mountain in Ireland, Carrauntoohil, is located in a nearby mountain-range, not too distant from the coast of Kerry, in the far south-west. Ancient mariners set on a northerly course around the coast of Iberia could not have missed Ireland. The closest point of Ireland to Iberia- the mountainous south-west- acted as a natural landmark, serving a function akin to a daytime light house which alerted seafarers that they were approaching the coast of Ireland from a comfortable distance.

The first sight of Ireland for sailors heading north from coastal Spain would have most likely been the peak of Mt Gabriel (a taller peak a little further to the north, Hungry Hill was another possibility, depending on the angle of approach).

The fact that Mt Gabriel was one of the first peaks to come into view may be of significance, as green staining is evident on rocks on the east face of the mount, an indication of the presence of copper minerals. This was clearly noticed by early prospectors, and there is surviving evidence for early copper mining activity at Mt Gabriel. Thus, from the perspective of a copper-age prospector sailing in the direction of Ireland from Iberia, even the very first glimpses of Ireland might have been enough to pique their curiosity.

Copper-Age Iberia: A School of Mining

One of the strongest arguments pointing to Iberia, rather than France, as the point of origin for Ireland’s mining pioneers rests on the fact that there was almost certainly very large population of miners in Iberia at the time that the mine at Ross Island came to life.

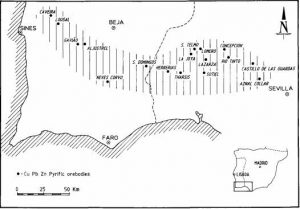

The geology of Iberia was, and still is, host to extensive and valuable mineral deposits, the most notable of these being the massive mineral belt known as the Iberian Pyrite Belt, famous for the Rio Tinto mining region that is found within its boundaries, as well as for being one of the greatest concentrations of pyrite on the planet, stretching across south-western Spain and into Portugal.

Iberia, modern Spain and Portugal, was the largest mining area of ancient Europe.

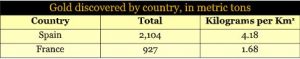

In the 1990s, a study by the geologist Donald Singer attempted to estimate the total tonnage of five metals (gold, silver, copper, zinc and lead) that had been discovered in the World up until that point. The study included estimates of the total percentage that had been found within the boundaries of the major mineral-producing jurisdictions. The share of the Iberian countries, Spain and Portugal, are notable.

The study estimated that over 1% of the world’s gold had been found in Spain, and while taken at face value that figure may not look particularly impressive, this must be weighed up against the finding that 62% of the world’s gold had been discovered in just four countries (South Africa, the United States, Australia and Canada).

Looking at Europe in isolation, more gold has been identified in the territory of modern day Spain than from any other European jurisdiction.

The table below, based on the data from the Singer study, highlights gold tonnage identified over time in Spain and France, which have been the two most prodigious gold producing territories in Europe.

Apart from these, the territory of the former Yugoslavia was noted as containing the second largest tonnage of gold discovered in Europe prior to the breakup, with gold discovered in that country estimated at 1078 m/t, slightly higher than the output of France [14]

Of contemporary European territories, France sits in second place. But when relative size is accounted for Spain is a league ahead, with around two-and-a-half times as much gold having been discovered for every square kilometre of territory falling within the modern boundaries of that nation.

Spain, as well as, Portugal are also notable for the vast quantities of lead that have been identified in these countries, estimated at around 3.7% of the global pool of this metal, in addition to lesser (though still substantial) quantities of copper and silver.

Although the territories of two other European nations, Germany and Poland, have also made a substantial contribution the global mineral supply over time, the output of the Iberian countries has easily exceeded that of any other nation in Western Europe.

The significance of this is that during the copper age, Iberia would have been capable of supporting a greater number of mining communities than any other region on the Atlantic Coast of Europe. It is plausible that the Iberian region would have become a centre of mining expertise, in the same way that countries that dominate mineral production today are well known for exporting mining experts as they are for vast quantities of minerals.

Logically, the first miners of Ireland would have most likely hailed from a neighbouring region with a large population of mining experts, and as noted above, Iberia would have been the leading contender here by a wide margin.

The fact that the study by Singer concluded that gold production from the territory of Spain exceeded any other European nation may be another cause to suspect the Ireland’s first miners originated in Iberia. Earlier, reference was made to the fact that Ireland’s first gold objects appear at around the same time as the earliest objects of copper, and there can be little doubt that the two metals arrived in Ireland conjunctly.[15]

Historians generally concur that that locally sourced gold would have been insufficient to meet the needs of Irish metal-workers in the Bronze-age. In the 1970s, the scientist Alex Hartmann analysed a large number of prehistoric gold artefacts, and based on the levels of copper, silver and tin within the gold, deduced that that the earliest goldsmiths in Ireland probably relied on an Iberian source to meet the needs of their trade.[16] [17]

This conclusion did not receive overwhelming endorsement, and as noted above, there certainly would have been plenty of gold to be found in the territory of modern France in ancient times, and some of this probably made its way to Ireland. That said, Hartmann’s conclusion seems logical, given the simple fact that more gold has been produced from Spain than any other European country. It is also worth noting that Galicia- the closest region of Iberia to Ireland- also happens to be one of the most prospective Iberian regions for gold.

The argument that Ireland’s first miners originated in Iberia need not rest entirely on probability. The stone hammers found at Ross Island seem to have their closest parallels to those found at a mine in El Aramo in Cantabria, in the North of Spain,[18] so there is some archaeological evidence to back up the case for Iberian origins.

Islands of Copper

There is some reason to suspect that mineral-hunters of the Chalcolithic era might have considered islands to be particularly prospective for copper, a view which would lend to the notion that the isle of Ireland might also have offered promise for the red metal.

Iberian miners scoured nearby coastlines for new copper deposits.

The Latin word for copper, Cyprium, nods to Cyprus, an island that was one of the primary sources of copper for Mediterranean populations in the Bronze Age.

Cyprus was certainly not the only Mediterranean island famed for its copper mines: in the nearby Cyclades islands, a number of isles, most notably Kythnos and Serifos, were home to ancient copper mines. Sardinia, further to the west, was also well known for copper production.[19]

The Iberian Peninsula, too, resembles an island in some respects, with the barrier of the Pyrenes in the north-east serving to isolate the region from the rest of Europe.

Copper-hunters of the 4th Millennium might have scoured the Mediterranean, seeking out islands with copper potential. A brave few of these early prospectors might have been willing to venture beyond the Pillars of Hercules and into the vast Atlantic, but for most Iberia would have been the end of the line.

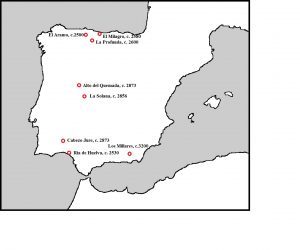

The earliest dated copper mine in Iberia is in the south-east, near the coastal Los Millares site, which appears to have commenced operation around 3200 BC. For at least a few hundred years, copper mining in Iberia seems to have been largely confined to the south-eastern Mediterranean coast of the peninsular (below).

Estimated dates for commencement of activity at some early copper mines across Iberia:. Sources referenced as follows: Los Millares[20], Ria de Huelva[21], Cabezo Jure[22], La Solana[23], Alto de Quemada[24], La Profunda[25], El Milagro[26], El Aramo[27]

A sample of ancient Iberian copper mines sites of the Chalcolithic period is represented above, illustrating the spread of copper mining across Iberia, first westwards from the Los Millares site, and then to the northern coast.

In the 29th century BC there seems to have been a sudden burst of activity in the west of Iberia: assuming the radiocarbon dates listed above are accurate, three of the mines depicted above, despite being as much as two hundred kilometres apart, sprang to life within the space of a generation: Cabezo Jure (c. 2873), La Solana (c. 2856) and Alto del Quemado (c. 2873).

What sparked this sudden frenzy of mining activity? This pattern looks suspiciously like a mineral rush, akin to the gold rushes of the 19th century, although in this instance ‘copper-rush’ would be presumably a more apt description. The likely trigger was probably the discovery of the mega-deposits in the Iberian Pyrite Belt, which would have resulted in some lucky early prospectors unearthing a treasure-trove of copper riches.

It is worth bearing in mind that tools found at the northern El Aramo mine apparently bore some similarities to those found at the Ross Island site. Carbon dating places the commencement of mining at El Aramo at circa 2500 BC[29], less than two centuries before the commencement of copper mining in Ireland. El Aramo appears to have been one of the last copper-age mines to have been founded in Iberia, and an increasingly competitive environment might have prompted some Iberian miners to cast their gaze northwards, across the Atlantic, and ponder whether greener pastures lay in the distant lands to the north.

One other point that is evident from the map above is that the ancient copper mines of Iberia are located overwhelmingly on the Western half of Iberia, and this geographic peculiarity would not have escaped the attention of ancient miners.

Although Ireland lies some distance from the northern coast of Iberia, virtually the entire island falls within the same longitudinal bracket as the western Iberian mining zone. This could have been one reason as to why ancient copper prospectors seem to have made a bee-line for Ireland, bypassing the western parts of Britain such as Cornwall, even though parts of this region are closer to the coast of Iberia. Based on their local experience, the ancient Iberian mineral explorers looking abroad might well have considered that the West was best.

The Iberian Pyrite Belt may have acted as a corridor, funnelling copper-mining expertise from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic[30]

The Iberian Pyrite Belt may have acted as a corridor, funnelling copper-mining expertise from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic[30]

The Book of Invasions

Now Ireland was waste thirty years after the plague-burial of Partholon’s people, till Nemed, son of Agnoman, of the Greeks of Sythia, reached it…

The speed of the transition from the Neolithic to the Metal Age in Ireland has the hallmarks of a revolution, and given the momentous significance of this period it is a fair assumption that it could have left an imprint in the popular memory of the population of pre-Christian Ireland.

Is it possible to detect any trace of this in the surviving early Irish origin stories?. The most notable of such stories were compiled in the Middle Ages, bound together in a work known as the Lebor Gabala Erenn, and this would seem to be the most obvious place to look.

The Lebor Gabala Erenn, known in English as The Book of the Invasions of Ireland, is an early Irish text that was compiled in the 11th Century, detailing a series of (mostly fruitless) attempts to colonise Ireland by varying groups. An interesting feature of the Lebor is that it employs a dating schemata, ascribing a date to each of the arrivals and other important events, based on the date at which it was believed that Adam was created (5199).

The sometimes baffling work is considered by most Historians to be largely a Medieval work of fiction aimed at formulating an origin story for the Irish based on classical and biblical precedents.[31] From time to time, however, a contrarian argument has been proffered by various writers to the effect that there could be elements of historicity in the Lebor Gabala, with parts of the work possibly deriving from ancient stories.[32]

Six groups of settlers are detailed by the Lebor, the first being the followers of Cessair, the second, a group led by Partholon, who were in turn followed by a group led by Nemed. The next two groups were descended from the band of colonists led by Nemed, namely the Fir Bolg and the Tuath De Danann. The sixth and last group, the Sons of Mil, were the final Conquerors of Ireland.

The once popular notion that the Irish people were descended from Spanish invaders stems from the legend of the Sons of Mil, and modern historians have few compunctions about pointing out the numerous holes in this old story.[33] It is possible, however, that this fixation with the Sons of Mil might have served to divert attention from the accounts of the earlier groups of arrivals described in the Lebor Gabala, some of which might have a stronger case for historical authenticity.

The first two groups of settlers, the followers of Cessair and Partholon end up meeting an untimely end, the former being wiped out by a flood, the latter by a plague. Nemed’s band enjoyed more success, occupying Ireland for over two centuries, but they too eventually leave, and the descendants of Nemed’s followers are said to have departed to different corners of the globe: one group heads to Britain, another is said to have headed for Greece, and the third group to the islands in the north.

Although never specifically spelt out by the text, it is possible that Nemed may have been a genuine historical figure connected to Ireland’s first mine at Ross Island. While this line of argument is invariably speculative, it is notable that a number of the dates in the story of Nemed in the Lebor Gabala seem to marry with the findings of modern dating techniques on the origins of copper mining in Ireland and Britain.

The Arrival of Nemed

Although the text is vague as to Nemed’s ultimate purpose in Ireland, intriguingly, the date given for Nemed’s arrival in Ireland seems to correlate quite well with the earliest mining activity at the Ross Island site.

The chapter concerning the conquest of Nemed begins with the line ‘From Adam till Nemed took Ireland, 2850′. This equates to 2349 BC, based on the date given for Adam’s creation determined by the scribe of the Lebor Gabala (5199 BC).

As noted earlier, archaeologists tend to agree that mining commenced at the Ross site around 2400 BC, based on the results of radiocarbon dating.[34] Thus, the date given in the Lebor Gabala for the arrival of Nemed’s people is very close to the best estimations for the earliest mining activity at Ross Island, a mere half century distant from the radiocarbon dating estimates for the earliest activity at the mine.

The date given in the Lebor Gabala for the arrival of Nemed’s people is very close to the best estimations for the earliest mining activity at Ross.

Interestingly, this is not the only date in the account of Nemed that seems to be backed up by modern methodology. The Chapter on Nemed describes how the Partholon, the predecessors to Nemed’s company, were wiped out in a plague thirty years prior to the arrival of the great leader (i.e. 2379 BC).

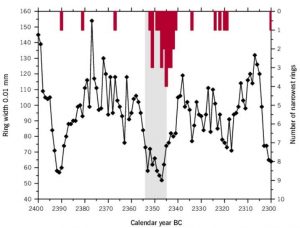

A dendrochronology study of samples of bog-oak in Northern Ireland carried out by Queens University, Belfast, concluded that had been two major environmental shocks within the past 7,000 years in Ireland that had resulted in severe stunting in the growth of the trees: the first of these, took place sometime between 2354 and 2345 BC.[35]

The second and more recent event took place during the historic period, around 540 AD. One of the most devastating pandemics in history, the Plague of Justinian, took place immediately after this environmental shock that impacted the growth in the oak trees.

It is a thus fair assumption that the similar earlier, prehistoric environmental shock that was identified by this study and which also stunted the growth of oak trees in the 24th Century BC may have likewise triggered a major plague. Certainly, such a major environmental shock of this nature would have devastated crops and resulted in a massive loss of life in agricultural communities in Ireland.

So the Lebor Gabala’s description of the population of Ireland being wiped out circa 2379 by some catastrophe is surprisingly accurate: about this time there was indeed a major environmental shock, and it may well have resulted in a plague as well.

Figure 3 Irish bog oak ring-width chronology 2400-2300 BC[36]

Closer examination of the data from the study, represented in the chart above, indicates that in the first half of the 24th Century BC there were in fact two clusters of years characterised by narrow tree-ring growth: the years leading up to, and including 2390, and the even more marked period referred to previously between 2354 and 2345.

Whatever it was that caused the stunted growth in oak trees in the late 2390s would have almost certainly adversely impacted agricultural crops as well, perhaps resulting in a famine. Plagues frequently follow in the wake of famine, and so the date given for the plague that devastated the community the Lebor calls the Partholon -2379- could fit in with the evidence from the tree-ring series highlighted above.

The tree-ring data also raises some questions about the date that archaeologists have generally ascribed to the beginning of the Ross Island mine, 2400 BC.

As described earlier, the Ross Island mine proved to be a highly successful operation, with mining activity at the site evident for centuries after the mine.

But if we assume that the Ross Island mine was founded in 2400 BC, as archaeologists have suggested based on radiocarbon dating, this would imply that the seeds of Ireland’s ancient mining industry were planted on the eve of a major catastrophe, apparently one of the most severe environmental shocks within the past seven millennia.

It would be a reasonable assumption that most of the miners, not to mention most of their customers, would have been wiped out by the terrible conditions that would eventuate in the baleful first half of that century.

2400 BC would thus have been an inauspicious year to launch a mine, and it seems difficult to believe that the operation could have survived the brutal years ahead had it been founded at the generally ascribed date of origin.

Radiocarbon dating is not as precise as tree-ring dating, and thus it may well be the case that the traditional date given for the commencement of mining at Ross could be several decades wide of the mark.

Perhaps the more opportune time to develop a mine would have been after 2350, when the worst of the lean years were over. From this perspective, the date given for arrival of Nemed in the Lebor Gabala, 2349, might in fact be a more plausible date for the commencement of mining at the Ross site than 2400 BC, the date which has been generally accepted by archaeologists.

It should be emphasised that there isn’t anything in the passages in the Lebor Gabala regarding Nemed’s group that directly indicates that Nemed or his followers were involved in mining activities. Having said that, it is interesting to note that there is not one, but two dates that link Nemed’s group with early mining activity in the British Isles.

Although according to the Lebor Gabala, Nemed himself died not long after his arrival in Ireland, the descendants of his followers are described in the text as departing Ireland 216 years after Nemed’s first landfall, heading to different corners of Europe, with one group venturing to Britain.

Based on the information provided in the Lebor Gabala, the departure of Nemed’s descendants from Ireland took place in 2133 BC.

This date more or less accords with the best estimates regarding the commencement of both copper and tin mining in Britain, generaly thought to have begun around 2100 BC, with the earliest copper-tin alloys dating back to this time.[37]

There are thus two dates that seem to link Nemed’s group to the nascent mining industry in Ireland and Britain.

But if we take a view that it was Nemed’s group that established the Ross Island mine, does this fit in with the suggestion that the first miners in Ireland were of Iberian origin?.

Based on the text of the Lebor Gabala, this would not seem to be the case. Nemed is introduced as being of the Greeks of Sythia, and his account begins with a description of Nemed and a fleet of thirty-four ships rowing from Sythia to the Northern Ocean, ultimately destined for Ireland.

The rather fanciful description of Nemed and his large group of followers rowing from Scythia to far-flung Ireland is rather difficult to take seriously, and is an example of some of the elements of the Lebor Gabala that have led many historians to dismiss the story as a Medieval fantasy.

It is worth noting, however, that an account of Nemed’s journey is found in a second, Earlier Medieval text, and intriguingly, the details of this account differ somewhat from those related in the Lebor Gabala

Nennius, in the Historia Brittonum, also provides an overview of the History of Ireland , including a brief summary of Nemed’s tale, based on what seems to be an earlier version of the account outlined in the Lebor Gabala:

…after having his ships shattered, arrived at a port in Ireland, and continuing there several years, returned at length with his followers to Spain.[38]

Nennius relation of this events is probably more reliable than that in the Lebor Gabala, in part because it is an earlier source.

Thus, the more reliable Historia Brittonum places the point of origin of Nemed’s company as Iberia, a region which, as noted previously, had a very large population of miners at this time. Given that the date of Nemed’s arrival in the Lebor Gabala also seems to correlate with the beginning of the Ross Island mine, it is quite possible that Nemed and his company were in fact a band of hopeful copper prospectors.

It is intriguing that the Historia Brittonum, the earliest source for the arrival of Nemed, is also the first historical source to describe the Ross Island Mine, and it is worth pondering where Nennius might have unearthed this information.

There is a possibility that Nennius might have relied on a common source for the information on Nemed and the Ross Island mine, and perhaps details of the Ross Island mine might have been included in an earlier account of Nemed’s story. At the very least, the inclusion of the Ross mine by Nennius in his list of ‘Wonders’ suggests that the significance of the mine was still acknowledged many thousands of years after its foundation.

Conclusion: Iberia to Ireland?

Based on the high level of expertise evident at the Ross Island Mine from the time of its inception, the first miners at the site could not have been locals. Historians seem to have some reservations about ascribing a point of origin to these pioneers, but as has been argued above, the evidence quite strongly points in the direction of Iberia.

Based on the high level of expertise evident at the New Ross Mine from the time of its inception, the first miners at the site could not have been locals.

As was observed in the study by Donald Singer, the mineral resources of the world are not evenly distributed, and a large share of the World’s gold, silver, copper, zinc and lead discovered to date are concentrated in a hand-full of mega deposits. The metallogenic province known as the Iberian Pyrite Belt is an example of one such major deposit. This concentration of valuable minerals would have been capable supporting a large number of copper-age mining communities, probably more so than any other region of Europe during the Copper Age.

The discovery of this major Iberian mineral belt in the early centuries of the third millennium BC was thus an important development in the history of mining, and was probably of significance for Ireland as well, serving to channel mining expertise from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic coast of Europe, and probably much further north.

The gulf between the shores of Iberia and Ireland is probably one of the reasons as to why historians have baulked at elucidating this connection, but ancient miners would have likely paid more heed to geology than physical distance, and the patchwork of Carboniferous and Devonian-aged rock that dominates the ancient mining territory within the Iberian Pyrite Belt is quite similar to the geology of south-western Ireland.

Metal-working and metal-mining seem to have been largely alien concepts in Ireland prior to the Ross Island Mine, and the dawn of the metal-working era might have left a lasting imprint on popular memory. It seems plausible that one of the groups of settlers outlined in Ireland’s Book of Invasions, the enigmatic followers of Nemed, might be connected to the pioneers who founded the mine at Ross Island. Certainly, it is curious that a couple of the dates given for the arrival of Nemed’s group in Ireland and Britain seems to concur with the best modern estimates regarding the onset of copper mining in these islands.

References

[1] Gibson, C, 2013. Out of the flow and ebb of the European Bronze Age: heroes, Tartessos and Celtic, Celtic from the West 2: Rethinking the Bronze Age and the arrival of Indo-European in Atlantic Europe, Oxford, p 74.

[2] O’Kelly, M, 1989. Early Ireland: an introduction to Irish prehistory, Cambridge, p 175.

[3] Koch, J.T, 2013. Westward ho?. Sword bearers and all the rest of it. Celtic from the West 2: Rethinking the Bronze Age and the arrival of Indo-European in Atlantic Europe, Oxford, p 135.

[4] O’Kelly, M, 1989. Early Ireland: an introduction to Irish prehistory, Cambridge, p 152.

[5] O’Brien, W, 2011. Prehistoric Copper Mining and Metallurgical Expertise in Ireland, Povoamento e exploração dos recursos mineiros na europa atlântica occidental, Braga p 338.

[6] Ibid. p 343.

[7] Gibson, C, 2013. Out of the flow and ebb of the European Bronze Age: heroes, Tartessos and Celtic. Celtic from the West 2: Rethinking the Bronze Age and the arrival of Indo-European in Atlantic Europe, Oxford, p 79.

[8] O’Brien, W, 2011. Prehistoric Copper Mining and Metallurgical Expertise in Ireland, Povoamento e exploração dos recursos mineiros na europa atlântica occidental, Braga p 354.

[9] Ibid. p 341.

[10] O’Brien, W, 2013. Bronze Age Copper Mining in Europe: Oxford Handbook of the Bronze Age, Oxford, p 444.

[11] O’Brien, W, 2014. Prehistoric Copper Mining in Europe, 5500 – 500 BC, Oxford, p 267.

[12] Harrison, R, 1988. Spain at the Dawn of History: Iberians, Phoenicians and Greeks, New York, p 152.

[14] Singer, D.A, 1995. World Class Base and Precious Metal Deposits- A Quantitative Analysis, Economic Geology, Vol. 90 p 88-90.

[15] Mallory, J.P, 2013. The Origins of the Irish, Thames & Hudson, London p 118.

[16] O’Kelly, M, 1989. Early Ireland: an introduction to Irish prehistory, Cambridge, p 175.

[17] Analysing ancient gold: an assessment of the Hartman database

[18] O’Brien, W, 2011. Prehistoric Copper Mining and Metallurgical Expertise in Ireland, Povoamento e exploração dos recursos mineiros na europa atlântica occidental, Braga p 345.

[19] O’Brien, W, 2013. Bronze Age Copper Mining in Europe: Oxford Handbook of the Bronze Age, Oxford, p 435.

[20] Gibson, C, 2013. Out of the flow and ebb of the European Bronze Age: heroes, Tartessos and Celtic. Celtic from the West 2: Rethinking the Bronze Age and the arrival of Indo-European in Atlantic Europe, Oxford.

[22] Saez, R. Nocete,F. Nieto, J. Capitan, A. Rovira, S. 2003. The Extractive Metallurgy Of Copper From Cabezo Jure, Huelva, Spain: Chemical And Mineralogical Study Of Slags Dated To The Third Millennium B.C., The Canadian Mineralogist, Vol. 41 p 627-638.

[23]Gibson, C, 2013. Out of the flow and ebb of the European Bronze Age: heroes, Tartessos and Celtic. Celtic from the West 2: Rethinking the Bronze Age and the arrival of Indo-European in Atlantic Europe, Oxford.

[24] Ibid.

[25] O’Brien, W, 2014. Prehistoric Copper Mining in Europe, 5500 – 500 BC, Oxford, p 100.

[26] Gibson, C, 2013. Out of the flow and ebb of the European Bronze Age: heroes, Tartessos and Celtic. Celtic from the West 2: Rethinking the Bronze Age and the arrival of Indo-European in Atlantic Europe, Oxford.

[27] O’Brien, W, 2014. Prehistoric Copper Mining in Europe, 5500 – 500 BC, Oxford, p 96.

[28] Cunliffe, B & Koch, J.T, 2010. Introduction, Celtic from the West: Alternative Perspectives from Archaeology, Genetics, Language and Literature, Oxford, p 1.

[29] O’Brien, W, 2014. Prehistoric Copper Mining in Europe, 5500 – 500 BC, Oxford, p 96.

[30] Gaspar,O & Pinto, A, 1991. The ore textures of the Neves-Corvo volcanogenic massive sulphides and their implications for ore beneficiation, Mineralogical Magazine, Vol. 55 p 417-422.

[31] Mallory, J.P, 2013. The Origins of the Irish, Thames & Hudson, London p 118.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Ibid. p 211.

[34] Fitzpatrick, A.P, 2013. Beakers into Bronze: tracing connections between western Iberia and the British Isles. Celtic from the West 2: Rethinking the Bronze Age and the arrival of Indo-European in Atlantic Europe, Oxford, p 55.

[35] Ancient oak rings can tell what happened long ago, Irish Times, 1999

[36] Baillie, M & McAneney, Jonny. (2015). Why we shouldn’t ignore the mid-24th century BC when discussing the 2200-2000 BC climate anomaly. 10.13140/RG.2.1.2657.8324.

[37] O’Brien, W, 2013. Bronze Age Copper Mining in Europe: Oxford Handbook of the Bronze Age, Oxford, p 440