Opinion: Did the ambush at Soloheadbeg begin the Irish War of Independence?

By John Dorney

On January 21 1919, the First Dail – the rebel parliament of the unilaterally declared Irish Republic – met in Dublin’s Mansion House.

One the same day, a party of Irish Volunteers ambushed two Royal Irish Constabulary policemen who were escorting a quantity of gelignite explosive to a quarry, at Soloheadbeg county Tipperary. It appears that when challenged, the constables reached for their guns and were both shot dead.

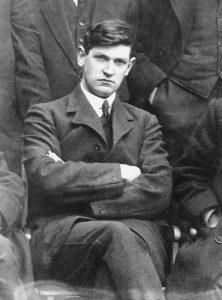

Dan Breen claimed that the ambush at Soloheadbeg single-handedly started the War of Independence.

The Soloheadbeg ambush has taken on disproportionate importance due to its coincidence with the meeting of the first Dail and is commonly presented as the ‘first shots of the War of Independence’. Dan Breen, one of the ambushers, in later years went out of his way to present the Soloheadbeg ambush as a premeditated act, designed to provoke a military conflict and to prevent political compromise to prevent the Volunteers (soon to be renamed Irish Republican Army or IRA) becoming a mere auxiliary to the political party Sinn Fein.

But Breen had his own reasons for doing this. One was merely self-aggrandisement; asserting his role in changing the course of Irish history. Another was perhaps to justify his anti-Treaty stance in the Civil War of 1922-23 – that the ‘soldiers of the Republic’ had at the outset of the independence struggle not waited for permission from the Irish parliament but had forged ahead on their own towards securing complete Irish independence.[1]

Other Volunteers at the time and since doubted that Soloheadbeg was more than an operation that went wrong. They thought that the Tipperary men had expected the RIC to surrender their arms and explosives and opened fire when the police refused and went for their own weapons. The account of Seamus Robinson, the Volunteer from Belfast who was actually in command of the ambush party that day, essentially backs up this version. [2]

Violence in 1917 and 1918

Whatever one thinks exactly happened at Soloheadbeg however, there are a number of other problems with the idea that incident marked the ‘first shots of the war of independence’. One problem is that it did not mark the beginning of political violence in post-Easter Rising Ireland, nor even a significant escalation of it.

In 1917 and 1918 rioting became common between the Volunteers and police, due to the banning of public demonstrations and military style drilling under the Defence of the Realm Act. And this type of violence did produce fatal casualties.

A Dublin Metropolitan Police Inspector died in a riot in 1917 after being hit over the head while breaking up a republican meeting. The Republican roll of honour ‘The Last Post’ records two Volunteers killed by the RIC in rioting 1917 and two more who died after being bayoneted by British troops in rioting in 1918 [3]

There was already a significant level of political violence in Ireland in 1917 and 1918, which produced fatal casualties.

Volunteer leader Tomas Ashe died of force feeding while on hunger strike. Another Volunteer in Clare was shot dead by the police during a ‘cattle drive’ in 1918.

Secondly, in the context of the Conscription Crisis of 1918, which witnessed a mass mobilisation in Ireland against the attempt to impose conscription, and the ‘German Plot’ in which most of the senior Sinn Fein figures were arrested, the revitalised Volunteers began raiding the RIC for weapons in order to try to rearm the organisation. In most cases policemen were disarmed without loss of life, but as it did at Soloheadbeg this activity too produced fatalities in 1918.

Two Volunteers were shot dead in a gun battle with the RIC at Ballymacelligot in Kerry in an arms raid on a police barracks.[4]

There were also widespread arrests of republican activists. Of the 73 Sinn Fein MPs elected in the General Election of December 1918, all but 27 were imprisoned when the Dail opened in January of the following year.

Thirdly, the shootings at Soloheadbeg did not mark a sea change in Volunteer or IRA strategy in early 1919. Richard Mulcahy the Volunteer chief of staff was extremely unhappy with the killings, believing that, being unauthorised, they showed indiscipline and risked undermining popular support for the republican movement. [5]

Michael Collins, the Director of Intelligence and President of the secretive Irish Republican Brotherhood thought otherwise, sheltered the Tipperary men in Dublin and employed them on other operations along with Dublin Volunteers who went on to form his ‘Squad’ or assassination unit. That he overruled Mulcahy (his notional superior) says something about the behind-the-scenes power that the ‘Big Fella’ was amassing.

Assassinations

There were a further 19 people killed in political violence in 1919, most being selective assassinations by Collins’ men.

The most prominent victims included several G Division detectives of the Dublin Metropolitan Police. Collin’s decision to begin assassinations of DMP detectives in September 1919 – the first Detective Patrick Smyth was killed on September 8 1919 – marks a much clearer watershed than the ambush at Soloheadbeg. Directly in response to the shooting of Smyth, the British banned the Dail as an illegal assembly.

DMP detectives compiled intelligence on separatist organisations and identified republican figures for arrest. None were killed before September 1919 but five were shot dead by Collins’ men before the end of the year and a further three detectives were dead by March 1920, effectively disabling the G Division.[6] Collins also attempted to kill the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, Sir John French near his residence in Dublin’s Phoenix Park in December 1919, but the only victim of the shootout was a Volunteer, Martin Savage.

A handful of other shootings, such as the celebrated Knocklong train ambush in which two policemen were killed – were local affairs aimed at freeing prisoners. A total of 11 RIC policemen and one British Army soldier were killed in 1919 by the IRA.[7]

On the other side, seven Volunteers as well as a number of other civilians were killed by British forces in 1919. [8] This was still, notwithstanding Collins’ campaign of assassination, a constrained level of political violence.

War: 1920-1921

However, in early 1920 Collins and Mulcahy made the decision to direct all Volunteer or IRA units to go on the offensive and to attack local police barracks wherever they could. In contrast to 1919’s relatively low figures for fatal political violence in Ireland, the IRA lost 252 Volunteers killed in 1920[9] while over 200 policemen [10] and 62 British Army soldiers were killed.[11]

Furthermore, about two thirds of these deaths took place in the second half of the year, after the British government had taken the decision to raise and deploy new paramilitary police corps -the Black and Tans and Auxiliaries – and to put down the insurgency rather than to negotiate with Sinn Fein. The following year up until the truce of July 11, 1921, would be bloodier still, with over 1,000 further deaths before the truce.

Michael Collins’s decision to begin trageted assassinations in September 1919 and IRA GHQ’s order to begin barrack attacks in 1920 mark the real start of military conflict.

In terms of a ‘war’, January 1920 was the real start of the War of Independence. But rather than look for single moments when ‘war’ proper started, it is more realistic to see the conflict as a series of escalations on both sides.

Political violence never went away after the Rising of 1916. The mass arrest of Sinn Fein activists in early 1918 raised the stakes further as did the increased militancy of the Volunteers during and after the conscription crisis. Soloheadbeg –an arms raid with unusually bloody results -can probably be fitted better into this pattern than as a premeditated plan to ‘start a war’.

Collins’ attempt to decapitate the DMP detective division led to the banning of republican political organisations, leading in turn to his and Mulcahy’s orders to attack barracks all over the country in early 1920. Finally the apex of violence was reached when Lloyd George’s government decided to put down what they called the ‘murder gang’ by force in the summer of 1920.

Violence escalated further until both sides agreed to a truce and to negotiations in the summer of 1921. Dan Breen, in short was not as important as he thought.

References

[1] For Breen’s account see his BMH statement WS1739

[2] See Daniel Murray, Seamus Robinson’s War of Independence.

[3] The Last Post p97-99. Abraham Allen of Cork ’died of wounds inflicted by the RIC’ 26//61917, Daniel Scanlon of Ballybunion’shot by the RIC during victory celebrations’ [presumably of Sinn Fein victory in the Clare by election] 11/7/1917. Thomas Russell of Balyferriter, Kerry, ‘stabbed to death by British Army’ 30/3/1918, Patrick Duffy, Castleblaney Co Monaghan, ‘Murdered by British forces, stabbed to death’ 4/6/18

[4] Ibid. John Brown and Richard Laide.

[5] See Marian Valiulis, Richard Mulcahy, Portrait of Revolutionary (1992) p38-39. Mulcahy remarked that the ambush was ‘outrageously propagandised’ and that ‘bloodshed should have been completely unnecessary in light of the kind of episode it was’. For Collins’ reaction, ibid. p47-48

[6] See DMP Roll of Honour http://www.policerollofhonour.org.uk/forces/ireland_to_1922/dublin/dmp_roll.htm

[7] RIC Roll of Honour http://www.policerollofhonour.org.uk/forces/ireland_to_1922/ric/ric_roll.htm

[8] The last Post p99

[9] The Last Post p99-113. A further 300 were killed in 1921.

[10] See the RIC roll of honour https://www.theirishstory.com/2018/04/24/a-declaration-of-war-on-the-irish-people-the-conscription-crisis-of-1918/#.XEXOFmngrIU

[11] This site has a list of all British Army casualties in Ireland in the period. https://www.cairogang.com/soldiers-killed/list-1921.html