“The Pope is the enemy of Irish Republicanism and Irish independence” Should we commemorate the Catholic Church’s role in the War of Independence?

By Padraig Og O Ruairc

Introduction – Ignoring faith and misrepresenting history?

The official state commemoration marking the centenary of the Soloheadbeg Ambush and the start of the War of Independence began with a Catholic mass celebrated by the Archbishop of Cashel Kieran O’Reilly.[1]

Archbishop O’Reilly’s prominence at the commemoration was interesting given that when the ambush occurred his predecessors including Monsignor Ryan, the Parish Priest of Tipperary, denounced Soloheadbeg as a criminal act perpetrated by a gang of murders: – “God help poor Ireland if she follows this deed of blood. But let us give her the lead in our indignant denunciation of this crime against our Catholic civilization.”[2]

It has been claimed that the role of the Catholic Church in the Irish independence struggle has been overlooked.

The day after the Soloheadbeg commemoration another state ceremony was held in Dublin’s Mansion House to mark the centenary of the inaugural meeting of Dáil Éireann. This commemoration was criticized by Gabriel Doherty, a historian who lectures at University College Cork, because Doherty claimed that the Catholic Church had played an “important role” during the 1916 Rising that the important role of the church during the War of Independence is was being overlooked because of “the reaction against the Church in recent decades.”

Doherty’s main argument was that ‘The Democratic Programme’ adopted by Dáil Éireann in 1919 contained sentiments that were “Catholic all over” but that the historians and politicians involved in the commemoration were ignorant of this.

Although Doherty acknowledged that Thomas Johnson the leader of the Irish Labor movement wrote the original draft, he claimed that “he [Johnson] wasn’t the author of the text which was endorsed by the Dáil”. Doherty suggested that the credit for the document should go to Seán T.O’Kelly a Sinn Féin T.D. who was allowed to edit the final draft of the document.

Furthermore Doherty suggested that the imprint of Catholic social teaching was evident in the document and warned that “Ignoring the role of faith in the fight for Irish freedom misrepresents the history of the struggle.” The Irish Catholic newspaper published Doherty’s comments on the front page of its 24th January issue under the headline “Call to honor Church’s key role in the fight for independence.”[3]

David Quinn, leader of The Iona Institute and a former editor of The Irish Catholic, wrote a piece for the Sunday Times which was published on 27th January echoing Doherty’s claims that “the positive influence of the Church should not be overlooked” and stated that “Catholic clergy played a big part in 1916 and many of the rebels had a strong Catholic faith.” -However Quinn expanded on this by suggesting that there should be a stronger emphasis on “nationalism” in commemorations and that the struggle to set up an Irish Republic had a lot in common with “the impulse behind Brexit”.

These calls to celebrate the contribution that the Catholic Church allegedly made to the cause of Irish freedom come at a crucial juncture when Irish people are starting to give serious consideration as to how to commemorate the centenaries of the War of Independence. Doherty and Quinn’s calls for a focus on Catholicism in upcoming commemorations are reminiscent of a similar call by the Catholic Archbishop of Dublin, Diarmaid Martin. Archbishop Martin wrote a piece in the Irish Times published on the eve of the Centenary of the 1916 Rising which criticized the “clinically secular concept of the way 1916 will be marked” and claimed that the contribution Catholic priests made towards the Rising was being ignored.[4]

An effort is being made to re-write, or at least re-interpret the history of the Catholic Church during the 1916 Rising and War of independence to promote a more positive interpretation of the Catholic Church’s role in the struggle for Irish Independence. The purpose of this article is to examine the specific claims of Doherty, Quinn and Archbishop Martin before assessing the history of the Catholic Church’s attitude towards Irish Republicanism, and its role during the 1916 Rising and War of Independence.

The Democratic Programme

Regarding Doherty’s claim that Sean T. O’Kelly was the author of the final draft of Democratic Programme of the First Dáil, It has always been known that Johnston a Socialist wrote the initial draft of the Democratic Programme and that O’Kelly watered down some of its stronger left-wing sentiments.

However, the final draft adopted by the Dáil was still quite radical and left-wing in its ideology.

Johnston was present at the inaugural meeting of Dáil Éireann and was reported to have been so happy at witnessing the approval of the final draft that he wept tears of joy – so there can be little doubt that the core substance of Johnson’s socialism remained despite O’Kelly’s editing.

Contrary to suggestions that the Democratic Programme of 1919 was Catholic inspired, it was written by Thomas Johnson, a socialist born in Liverpool of Unitarian upbringing.

Suggestions that O’Kelly was more significant in writing the Democratic Programme than Johnson are tantamount to stating that J.K. Rolling’s editor was more responsible than she was in writing Harry Potter!

Rather than restoring O’Kelly, an Irish-Catholic, to his rightful place in history, Doherty’s interview with The Irish Catholic downplays the important role of Johnson, an English-born Protestant (Unitarian), and perpetuates an oversimplified history which associates Irish Republicanism with Catholicism. Doherty’s suggestion that modern day hostility to church in an increasingly secular Ireland has led to a cover-up of the Church’s “key role” in the struggle for Irish freedom is questionable.

The Catholic Church has a long record of opposing Irish Republicanism stretching back to the 1790’s and continuing throughout the 1916 Rising and War of Independence – the only “cover-up” was the one which decades later sought to gloss-over the church’s collaboration with the British.

Concerning David Quinn’s claim that nationalism “was the dominant motive behind Irish independence” during the Irish revolution of 1913 -1923; I would suggest that the ideology of Irish Republicanism was the dominant motive behind the establishment of the Irish Republic.

There is a significant difference between the politics of ‘Catholic-Nationalism’ and ‘Irish-Republicanism’. It is remarkable that Quinn managed to write a lengthy article about the foundation of the Irish Republic without mentioning Republicanism once but he managed to cram numerous references to ‘Nationalism’ and Brexit into his article.

Quinn’s analogy between the War of Independence and Brexit is unsound. It is not a valid comparison to equate Britain’s colonial project in Ireland which the Irish were forced to fight a war to exit, with the United Kingdom’s membership of the European Union which the British public chose to enter, and later leave by the simple means of a referendum.

The Catholic Church and the British connection.

As far back as the 1798 rebellion Catholic clergy in Ireland actively supported British rule. The clergy were appalled by the secularism of the United Irishmen’s leaders like Robert Emmet whose proclamation called for the abolition of church tithes and the nationalization of all church property.[5]

John Troy, the Catholic Archbishop of Dublin, denounced the United Irishmen as an anti-religious conspiracy whose aim was “To destroy the salutary influence of our clergy in this kingdom.”[6]

Meanwhile the British government helped to establish the Catholic Seminary at Maynooth College in 1795. In the words of Lord Russell : “Britain has tried to govern Ireland by force and conciliation and failed No other means are now open to us except those we are now using, namely, to govern Ireland through Rome.”[7]

The Catholic Church condemned both the United Irishmen of 1790s and the Fenians of the 1860s

When the Fenians plotted an uprising in the 1860’s the church was amongst their staunchest opponents. The Fenian Proclamation of 1867 called for “the complete separation of church and state”.[8] Cardinal Paul Cullen declared that the church would “wage an unrelenting war on the [Fenian] organization”[9], while Bishop Moriarty of Kerry invoked: “God’s heaviest withering, blithing, blasting curse on these Fenian bastards… Hell is not hot enough, nor eternity long enough for such miscreant!!”[10] Pope Pius IX issued a decree in 1870 condemning Fenianism as “… the enemy of the Church and the [British] State” effectively excommunicating all Catholic Fenians.[11]

For the Catholic Church the key to battling Irish Republicanism with its inherent sedition, secularism and anti-Clericalism was control of the education system. The Fenian’s fiercest opponent Archbishop Cullen declared in the aftermath of the 1867 Rising: “This ought to convince the British Government that education without religion is will promote revolution.”[12]

And Indeed the Catholic Church was largely granted control over the education of Irish Catholics after 1831. In that year the British Government established the National Board of Education for Ireland and the Catholic Church gained control of the new National School system which they used to indoctrinate future generations with the tenets of the Catholic faith. While it was often alleged that the Church education encouraged Irish militant Irish nationalism, the education children in Catholic run National schools received was Catholic in religion, predominantly English in culture, and was actively hostile towards the Irish language.

Cork IRA leader Tom Barry, recalled: “The Jesuits taught us to rhyme off the names of the Kings of England but nothing of Wolfe Tone or 1798.”[13] Where nationalist history was taught its was given a distinctly Catholic flavour. Dublin IRA volunteer Todd Andrews, was educated by at the Christian Brothers just before the 1916 Rising:

“Contrary to an assertion often made, the Brothers did not deliberately indoctrinate their pupils with hostility to Britain. …We were taught much about the saints and scholars and … we heard rather less about Wolfe Tone and not much about the Fenians. It was a very simplistic history. … Fr Murphy had become a symbol of faith and fatherland. The fact that he was a rare almost unique example of clerical participation in the 1798 rebellion was never referred to; the general opposition of the Church to the rebellion was conveniently forgotten.”

The 1916 Rising

The 1916 rising is often portrayed as an event steeped in Catholicism because its leader, Patrick Pearse, was a devout Catholic and the insurrection coincided with the Christian holiday of Easter. However the fact that many Protestant-Republicans, veteran Fenians, Suffragettes and Socialists were involved shows that the 1916 Rising was inspired more by radical political ideals than religion.

The Catholic hierarchy certainly did not view the Rising as a Catholic rebellion. Michael Kelly, the Irish-born Arch-Bishop of Sidney denounced the 1916 Rising as “anti-Patriotic, irrational and wickedly irreligious.”[14] Seven other Catholic bishops based in Ireland emphatically condemned the 1916 Rising.[15]

Throughout Ireland Catholic priests condemned the insurrection and at the British inquiry into the rebellion Inspector Gelstone of the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) testified “Any of the priests who had Sinn Féin tendencies were young. The older priests and the parish priests spoke against the movement.”[16] The Vatican continually telegraphed the Irish bishops during the Rising urging them to use their influence to get the Republicans to surrender.[17]

That the leader of the Rising Patrick Pearse had a deep Catholic faith is not in doubt – but as the son of a Catholic-Irish Mother and a Unitarian-English Father who espoused Freethinking, Pearse’s own views on religion and its role in society were complex and nuanced.[18]

James Connolly espoused secularism in politics and stated that “Catholic, Protestant, Jew, Freethinker, Buddhist and Muslim will cooperate together … to abolish the capitalist system

Pearse’s play “The Singer” set in Galway during the 1798 Rising was critical of the church’s role in political matters. The character Maolseachlainn tells the audience: “Some [priests] said there was irreligion in them [the rebels] and blasphemy against God. But I never saw it and I don’t believe it, but there are some [Catholic bishops] who would have us believe that God is on the side of the foreign oppressor.”[19]

Interestingly Pearse himself was later accused of blasphemy by a Jesuit for having declared that the grave of the Protestant-Republican Wolfe Tone, was “the holiest place in Ireland, Holier even than where Saint Patrick sleeps in Down.”[20] Pearse understood the views of others and joked that: “The prospect of the children of [Belfast Protestant district] Sandy Row being taught to curse the Pope in Irish with a Belfast accent is rich and soul satisfying”[21]

Another of the 1916 leaders James Connolly espoused secularism in politics and stated that “Catholic, Protestant, Jew, Freethinker, Buddhist and Muslim will cooperate together … to abolish the capitalist system [and build a Socialist-Republic]”.[22] Connolly had continually condemned the interference of the Catholic Church in Irish politics and stated “the church has always accepted the establishment … and denounced every revolutionary movement … yet allowed its priests to deliver speeches in eulogy of those movements a generation afterwards.”[23]

At least one of the republican leaders, Thomas Clarke, a Fenian veteran, went to his death without spiritual aid and in conflict with the Catholic Church. Hours before his execution a Catholic priest refused Clarke the sacraments of absolution and communion unless he would first accept the church’s teaching that the rebellion had been wrong and sinful. Clarke’s wife who met both him and the priest immediately before the execution recalled Clarke telling her: “I told him [the priest] to clear out of my cell quickly… To say I was sorry would be a lie and I was not going to face my God with a lie on my tongue.”[24]

There is no doubt that the leaders of the Rising were Catholics who had a deep personal religious faith, but equally all of them were Irish Republicans who were opposed to the Catholic Church’s interference in political matters. All of the leaders of the 1916 Rising, with the sole exception of James Connolly, were members of the Irish Republican Brotherhood whose constitution (Article 18) supported the separation of church and state – “In the Irish Republic there shall be no state religion but every citizen shall be free to worship God according to his conscience, and perfect freedom of worship shall be guaranteed as a right and not granted as a privilege.”[25]

The pluralism of the leaders of the 1916 Rising is also reflected in the 1916 Proclamation, which stated: “The Republic guarantees religious and civil liberty, equal rights and equal opportunities to all its citizens, and declares its resolve to pursue the happiness and prosperity of the whole nation and of all its parts, cherishing all the children of the nation equally”.[26]

Following the 1916 Rising the IRB’s constitution was updated in 1918 with the insertion of another clause that guaranteed class equality: “There shall be no privileged persons, or classes, in the Irish Republic. All citizens shall equally enjoy equal rights therein.”[27]

When the War of Independence began in January 1919 many of the Sinn Féin TD’s elected to the First Dáil and several members of the IRA ambush party at Soloheadbeg were also members of the Irish Republican Brotherhood – their concept of a republic was one which embraced religious freedom and would not give the church a privileged status in a free Ireland.

The Catholic Church’s condemnation of Sinn Féin.

Throughout 1917 and early 1918 the Irish republican struggle was more political than military in nature as the newly reformed Sinn Féin party stood candidates in several by elections in 1917 before winning a landslide political victory in the 1918 General Election in Ireland.

The East Clare By-Election of July 1917 was one of the first electoral contests facing Sinn Féin and their candidate, the 1916 Rising veteran Eamon de Valera, faced stern opposition from many of the local Catholic priests.

One of the leading anti-Republican Clerics in the county was Father Michael Hayes, The Parish Priest of Feackle, who denounced Sinn Féin as having “a policy of socialism, bloodshed and anarchy which struck at the root of authority, peace and Christianity” and he condemned Sinn Féin for posing “a great danger to our country and our religion”.[28]

Many clerics were hostile to the rise of Sinn Féin in 1917-18, though the Church as a whole did not condemn the party.

A few of the younger priests in Clare did support de Valera, but the more senior Parish Priests were solidly behind de Valera’s opponent. The Catholic Bishop of Killaloe Dr. Fogarty steadfastly refused to comment on which candidate should be supported until after the result was announced when Bishop Fogarty swiftly broke his silence to announce he had voted for the winning candidate – de Valera!

In the Kilkenny City by-election of August 1917 Sinn Féin faced opposition from the Bishop Brownrigg of Ossary, who wrote to the press attacking Sinn Féin. The people ignored the Bishop, and the Sinn Féin candidate won by a landslide.

Following the series of Sinn Féin victories in the 1917 by-elections it was obvious that there was a groundswell of support for Sinn Féin and that many senior clergy were out of touch with their flock. In early 1918 the “Conscription Crisis” forced Sinn Féin into a temporary political alliance with the Catholic Church and the Irish Parliamentary Party who all had a common platform in opposition to the extension of British military conscription to Ireland.

By December 1918 the Irish Parliamentary Party were a spent force throughout most of southern Ireland and it seemed likely that Sinn Féin were destined to sweep the electoral boards. It was a different story in Ulster however where the Irish Parliamentary Party still had a great deal of support and the Catholic Church in the north brokered an electoral pact between the two parties in an attempt to prevent conflict and guarantee their candidates did not split the Republican-Nationalist vote to the advantage of the unionists.

By the time of Sinn Féin’s landslide victory in the 1918 General Election in Ireland Catholic criticism of the party had become more muted but even after this there were still occasional outbursts of criticism from the clergy.

In April 1919 Bishop Kelly of Ross condemned Constance Markievicz, Richard Corish and other Sinn Féin TD’s for expressing support for the Russian Revolution and declared that Irish Republicanism would lead to the “devastation and destruction”. Bishop Kelly had a few weeks earlier, banned the saying of prayers in churches in his diocese for the Sinn Féin T.D. Pierce McCann who had died in an English prison.[29]

The Catholic clergy’s condemnation of the IRA during the War of Independence.

Whatever ambivalence the Catholic clergy showed towards the rise of Sinn Féin, they were unequivocal in their condemnation of political violence in pursuit of the Irish Republic in the years afterwards.

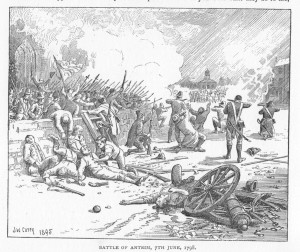

The Sunday after the Soloheadbeg Ambush Cannon Ryan, the Parish priest of Tipperary, condemned the IRA as “murderers with blackened faces and blackened hearts who gave their victims no chance .[30]

Father Slattery of Soloheadbeg condemned the ambush as “a shocking criminal affair” whilst his colleague Father Keogh condemned the attack as “ a frightful outrage … worse than the crimes of Bolshevik Russia”.[31]

The Catholic clergy were unequivocal in their condemnation of political violence in pursuit of the Irish Republic.

Another priest Father Condon declared; ‘No good cause would be served by such crimes which would bring on their country disgrace and on themselves the curse of God.’ One of the participants in the ambush Dan Breen later stated “It’s a terrible pity that we didn’t shoot a few bishops!”[32]

Condemnation of the IRA’s military campaign by the clergy did not end with Soloheadbeg, it continued week after week for the next two years. Bishop Gaughran of Meath condemned the IRA as “criminals … as savage as the bushmen of the forest.”

Father John Burke of Menlough, Galway ridiculed the IRA as “tin-pike soldiers who think they can beat England”. Father Enright of Miltown Malbay, Clare denounced the IRA’s struggle as “absolute insanity” and proclaimed that “It is folly to make an attempt to overthrow the power of the British Government”. Bishop MacRory of Down and Connor stated that the IRA were “atheists and nihilists”.

Father Gleeson of Lohrra placed a “curse” on the IRA: “May the curse of Cain, the curse of the priest and the curse of God fall on these [IRA] murderers!”[33] Archbishop Gilmartin of Tuam also denounced the IRA as “murderers” and cursed men “…who must answer before the bar of divine justice”.[34]

Excommunication – denying IRA Volunteers the Sacraments and Christian burial.

The clergy also used their spiritual authority to try and break the IRA’s resistance to British rule. On the 11th of December 1920 the IRA killed an RIC Auxiliary Cadet during an ambush in Cork City. That night members of the British forces retaliated by assassinating two IRA members and burning the centre of Cork.

The following morning the Bishop Conlahan of Cork, issued a pastoral decree, directed not at the British Forces, but against the I.R.A.. It declared that anyone taking part in an ambush was guilty of murder and would be excommunicated.

Given that the overwhelming majority of the IRA’s Volunteers were Catholics the bishop’s decree sparked outrage amongst republicans. A Sinn Féin member Cork City Corporation Councillor Ó Cuill attacked the Bishop saying; “He stands now only where his people [the clergy] always stood – in the wrong.”

After the burning of Cork in December 1920, Bishop Conlohan declared that anyone taking part in an IRA ambush was guilty of murder and would be excommunicated

The threat of excommunication and the refusal of sacraments were also widely used by priests in an attempt to break the will of IRA prisoners in British custody. Todd Andrews remembered Catholic priests visiting the republican prisoners on hunger in Mountjoy using their religious and social position to try and force them to end a hunger strike: “I had a visit from the prison chaplain. … he warned me that I was wilfully endangering my life which was an immoral act totally forbidden by the Commandments. … The chaplain was doing the dirty work required by his British employers.”[35]

Not content with merely demoralizing republican prisoners in British custody the Catholic Church were also involved in incarcerating some of those involved in the Republican movement – For example; Maria Bowles a thirteen year old girl whose older brother Mick Bowles was the IRA Quartermaster of the Colgheen Company of the IRA in Cork was captured by the British Forces whilst trying to hide arms in January 1921.

Bowles’ punishment for her assistance to the IRA was imprisonment in a Magdeline Laundry run by the Catholic Church. [36]Fortunately, Bowles comrades managed to secure her transfer and eventual release. Given the Catholic Church’s record in the War of Independence and Civil War it is unsurprising that the republican newspaper An Phoblacht was the only Irish newspaper in the late 1920’s and early 1930’s which openly condemned the exploitation of children in the Catholic Church’s institutions.[37]

Another method used by the Catholic clergy in an attempt to undermine the republican struggle was the refusal to hold funeral services for IRA Volunteers killed by the British forces.

Father Andrew Nestor, the Parish Priest of Ennistymon in Clare, refused to allow the funeral of IRA Volunteer Michael Conway who had been shot dead by the British Army to enter his church.[38] Likewise the Parish Priest of Murroe a Father Dwane had initially refused to allow the burial in the local graveyard of two IRA Volunteers who had been killed by the British Army in May 1921.[39] Throughout Ireland it was a common for the funerals of IRA Volunteers to be barred from entering Catholic churches on the orders of the clergy.

The month of December 1920 was key in the clergy’s attitude toward the IRA – that month two Catholic priests were killed by the British forces and in the aftermath of these shocking murders condemnation of the IRA by the church hierarchy either tailed off or became more nuanced in the final months of the war.

For example on the 20th March 1921 Bishop Finegan in Cavan called for prayers for the IRA volunteers IRA killed at Selton Hill in Leitrim and executed by the British in Dublin, whilst issuing a call condemning violence by both the British and IRA: ‘To be “shot while getting away” [the killing of IRA prisoners in British custody] and ambushing is murder. Ireland is not at war. Shooting of police and soldiers [by the IRA] is murder.’[40]

Spies, Informers & Priests – The Catholic Clergy and British Intelligence.

One of the most important military aspects of the War of Independence was the ‘Intelligence War’ waged between the IRA and the British forces. During the conflict the British Forces regarded Catholic Priests as a valuable asset and source of intelligence information:

“The informer is throughout Ireland held in abhorrence. This feeling made it very difficult to obtain information during 1920 – 21, … the bulk of the people were our enemies … [however one] class which could be tapped [for intelligence information] were, the clergy who generally are safe in Ireland whatever their religion.”[41]

Several priests acted as informers for British forces.

One of the most notorious Catholic priests to become an informer during the conflict was Father Hayes, the Parish Priest of Feakle in Clare. Thomas Tuohy a local IRA Volunteer recalled: “Fr. Hayes, a violent imperialist, strongly denounced the I.R.A. from the pulpit. He referred to us as a murder gang, and declared that any information, which he could get, would be readily passed on to the British authorities and that he would not desist until the last of the IRA murderers was strung up by the neck. … for some time afterwards services at which he officiated were boycotted by his congregation.” [42]

The Parish Priest of Newmarket-On-Fergus, Cannon O’Dea gathered information for the British Army and had it communicated directly to Captain Kelly the Intelligence Officer for the British Army’s 6th Divison. Father Flatley the Parish Priest of Aughagower, Mayo also spied for the British but the local IRA leader Thomas Heavey was refused permission to execute him by IRA Headquarters.[43]

Father Collins, a Dominican priest in Tralee, wrote letters to the local RIC Inspector identifying a woman who attended mass at his church as a republican sympathizer. Her home was subsequently burned by the Black and Tans.[44]

Tim Kennedy the IRA Volunteer charged with executing the Dominican for spying refused to do so even though he had previously executed two other spies. Kennedy’s comment in refusing was “I would submit myself to be put against the wall myself before I would do my ‘duty’ on a priest, no matter how bad he was”.[45] The likelihood is, as the British suggested, many priests throughout Ireland were informers but very few of them were ever exposed by the IRA.

Father Michael O’Flanagan and Republican priests.

A very small minority of priests actively supported the IRA, most notably Father Michael Griffin who was murdered by members of the RIC Auxiliary Division in 1920, and also two Capuchin Friars – Father Albert Bibby and Father Dominic O’Connor who were both transferred out of Ireland as a punishment for their political activities.

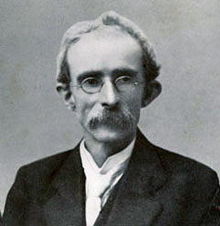

The most prominent priest who supported the Republican struggle during the War of Independence was Father Michael O’Flanagan from Roscommon.

O’Flanagan who was appointed Vice-President of Sinn Féin in 1917 was suspended from his priestly duties in 1918 because he canvassed for Sinn Féin in Cavan East by-election during which the local Bishop had called for the Irish Parliamentary Party to be elected unopposed.

O’Flanagan saw his political activity as a strictly secular civic duty stating “It is true that I am a priest, but I was an Irishman for twenty-four years before I became a priest … and the duties that the law of nature placed on me the law of no religious institution … can take away from me”.[46]

Father Michael O’Flanagan defied his bishops and served as vice President of Sinn Fein.

Throughout his life O’Flanagan was withering and unstinting in his criticism of the interference of Catholic bishops, priests and even the Pope in secular and political matters. “The judgement of Irish bishops may be excellent in religious matters but they are usually wrong when it comes to politics” O’Flanagan declared that the Catholic Church as an institution was being used as a weapon “to bludgeon the Irish People into submission.”

He denounced “Maynooth Rule” in Ireland and declared that

“The Pope is the enemy of Irish republicanism and Irish Independence … England rules Ireland with the help of the Pope!”[47] “[Catholics] are not bound to follow the political leadership of the Pope and any Catholic who slavish did so was unworthy of Irish citizenship of the citizenship of any country save the Vatican State.[48]

O’Flanagan continually espoused Irish Republicanism and throughout the 1930’s he remained in conflict with the Catholic hierarchy because he condemned Blueshirt-Fascism in Ireland, Francoism in Spain and Nazism in Europe whilst his superiors in the Catholic Church gave open support and active encouragement to all of these movements.

Conclusion

Although many lay-Catholics and a handful of younger Catholic clerics contributed to the Republican struggle during the Irish War of Independence there is no doubt that the overwhelming majority of the Catholic priests and especially the more senior ranks of the Catholic clergy were staunchly opposed to Irish Republicanism.

Any suggestion that the church as an institution played a leading role in the fight for Irish freedom and that a modern secular society has conspired to cover up this ‘hidden history’ is farcical. Any suggestion that the centenary commemorations of the War of Independence should place emphasis on Catholicism or afford the Catholic Church a special status are absurd.

In past generations, the Catholic Church’s propagandists largely succeeded in creating the impression that Irish Republicanism was equivalent to Catholic-Nationalism.

Although many lay-Catholics and a handful of younger Catholic clerics contributed to the Republican struggle, the overwhelming majority of the Catholic clergy were staunchly opposed to Irish Republicanism.

By contrast many Irish-people remain unaware of the history of secularism, pluralism and support for the separation of church and state within Irish Republicanism. During the Centenary of the 1916 Rising the Irish Times journalist Ronan McGreevy in his analysis and critique of the 1916 Proclamation of the Irish Republic linked the leaders of the 1916 Rising with the distinctly Catholic state that emerged in southern Ireland after 1922.

McGreevy stated “Survivors of the Easter Rising dominated the governance of independent Ireland … [which] developed a distinctly Catholic ethos … [that] contributed to a sense of alienation amongst Protestants”.[49] The fact is that whilst many of the politicians who were in government in the Irish Free State in the 1920’s and 1930’s had participated in the 1916 Rising or War of Independence they had abandoned the fundamental ideology and secular ideals of Irish Republicanism by the time that they set about building a Catholic-Nationalist state in southern Ireland.

The ideological foundations and roots of the conservative right-wing Catholic state that emerged in southern Ireland are not to be found in the ideology espoused by those who fought for a secular Republic in 1798, 1867 or between the years 1919 to 1923.

The foundations of the Catholic state that emerged in the 1920s were laid by the counter-revolutionaries on the pro-Treaty side of the Civil War who, with the support of the Catholic Church, took power in the Irish Free State in 1922. Indeed the Church was openly partisan in the Civil War, denying the sacraments to all anti-Treaty fighters and activists.

The leader of the Free State Government W.T. Cosgrave suggested that a “Theological Board” should be added as an addition to the upper house of the Dáil to ensure that the Irish government would not pass any legislation “contrary to the faith and morals [of the Catholic Church]”.[50] Likewise Kevin O’Higgins the Free State Minister for Justice proudly boasted that he and his fellow pro-Treaty politicians in the Cumann na Gaedheal Patry and the Free State Government “were the most conservative minded revolutionaries that ever put through a successful revolution.”[51]

More than a century ago the socialist historian and Irish language activist William Patrick Ryan wrote; “The most brilliant thing ever done by Irish Catholic priests was the invention of the legend that they had always been on the side of the people.”[52]

A century later there appears to be a renewed effort by an ailing Catholic Church to perpetuate this myth and rejuvenate itself through a revisionist project which is attempting to whitewash the church’s pro-British past and draft an alternative narrative which would allow them to exploit the popularity of the 1916 centenary celebrations and the commemoration of the War of Independence. Anyone who misrepresents our history should be challenged at every opportunity regardless of whether their revisionism has a political or religious purpose.

Dr. Pádraig Óg Ó Ruairc has a PhD in modern Irish history. He has written several books about the Irish Revolution of 1913 to 1923.

References

[1] Irish Examiner, 20th January 2019.

[2] Heffernan, Brian, Freedom and the Fifth Commandment – Catholic Priests and Political Violence in Ireland 1919 -1921. (Manchester, 2014), pp. 19

[3] The Irish Catholic, 24th January 2019.

[4] Irish Times, 23rd December 2015

[5] Maguire, W.A., Up In Arms – The 1798 Rebellion in Ireland, (Belfast, 1998), p.75, Robert Emmett, Proclamation of the Irish Republic, (Dublin 1803).

[6] Rafferty, Oliver J., Violence, Politics and Catholicism in Ireland, (Dublin, 2016), p. 18

[7] Rafferty, Oliver J., Violence, Politics and Catholicism in Ireland, (Dublin, 2016), p. 19

[8] Fenian Proclomation of the Irish Republic, 1867.

[9] Kenna, Shane, Conspirators, (Cork, 2015) p. 18

[10] Norman, E.R., The Catholic Church and Ireland in the Age of Rebellion 1859– 73, (Dublin, 1965),p.117.

[11] Rafferty, Oliver J., Violence, Politics and Catholicism in Ireland, (Dublin, 2016), p. 89.

[12] Norman, E.R., The Catholic Church and Ireland in the Age of Rebellion 1859 – 73, (Dublin, 1965),p. 96.

[13] Ryan, Meda, Tom Barry – IRA Freedom Fighter

[14] Carroll, Denis, They Have Fooled You Again: Michael O’Flanagan – Priest, Republican, Social Critic, (Dublin, 2016), p.157.

[15] Rafferty, Oliver J., Violence, Politics and Catholicism in Ireland, (Dublin, 2016), p. 29.

[16] The Times, Sinn Féin Rebellion Handbook, 1916.

[17] Rafferty, Oliver J., Violence, Politics and Catholicism in Ireland, (Dublin, 2016), p. 30.

[18] O’Donnell, Ruan, 16 Lives – Patrick Pearse, (Dublin 2016), p. 18.

[19] Pearse, Patrick, ‘The Singer’ in The Best of Pearse, (Cork, 1967), p. 113.

[20] Rafferty, Oliver J., Violence, Politics and Catholicism in Ireland, (Dublin, 2016), p. 40.

[21] Augusteen, Joost, Patrick Pearse – The Making of a Revolutionary” (London, 2010),p. 233.

[22] James Connolly-Heron, The Words of James Connolly (Dublin 1986), p. 56.

[23] James Connolly-Heron, The Words of James Connolly (Dublin 1986), p. 51.

[24] Clarke, Kathleen, Revolutionary Woman – My Fight for Ireland’s Freedom, (Dublin 1997) p. 93.

[25] Constitution of the Irish Republican Brotherhood – 1910 edition. Bureau of Military History, CD8/3 p.3

[26] It is important to note that in this instance all the children of the nation is a direct reference to children but an allegorical reference to different social and religious groupings in Ireland. Likewise when French Republicans sing La Marseilles – “enfants de la Patrie” does not refer literally to children but all French citizens.

[27] Constitution of the Irish Republican Brotherhood – 1918 edition. Bureau Military History, CD178/3/6 p.

[28] Ó Ruairc, Pádraig, Blood On The Banner – The Republican Struggle in Clare, (Cork, 2009).

[29] Heffernan, Brian, Freedom and the Fifth Commandment – Catholic Priests and Political Violence in Ireland 1919 -1921. (Manchester, 2014), pp. 19 – 20.

[30] Marnane, Denis G. The 3rd Tipperary Brigade – A History of the Volunteers/IRA in South Tipperary 1913 -21, (Tipperary, 2018), p. 181.

[31] Heffernan, Brian, Freedom and the Fifth Commandment – Catholic Priests and Political Violence in Ireland 1919 -1921. (Manchester, 2014), pp.44.

[32] Marnane, Denis G. The 3rd Tipperary Brigade – A History of the Volunteers/IRA in South Tipperary 1913 -21, (Tipperary, 2018), p. 167.

[33] Heffernan, Brian, Freedom and the Fifth Commandment – Catholic Priests and Political Violence in Ireland 1919 -1921. (Manchester, 2014), pp. 26, 30, 47, 56, 58.

[34] P. Murray, Oracles of God, The Roman Catholic Church and Irish Politics, 1922–37 (Dublin 2000), p. 409.

[35] Andrews, C.S., Dublin Made Me, (Dublin, 2001), p. 152

[36] NAUK, Colonial Office Papers, 904 / 168.

[37] Hanley, Brian, The IRA 1926 – 1936, (Dublin, 2002), p. 70.

[38] Heffernan, Brian, Freedom and the Fifth Commandment – Catholic Priests and Political Violence in Ireland 1919 -1921. (Manchester, 2014), p. 70.

[39] Toomey, Tom, The War of Independence in Limerick, (Limerick, 2011), p. 589. It was only when the local Protestant landowner Sir Charles Barrington offered to have the two republicans buried in his own family plot in a Protestant graveyard that Father Dwane relented.

[40] Anglo Celt March 26 1921.

[41] Record of the Rebellion in Ireland

[42] Thomas Tuohy, BMH Statement, Irish Military Archives.

[43] Heffernan, Brian, Freedom and the Fifth Commandment – Catholic Priests and Political Violence in Ireland 1919 -1921. (Manchester, 2014), p. 72

[44] Heffernan, Brian, Freedom and the Fifth Commandment – Catholic Priests and Political Violence in Ireland 1919 -1921. (Manchester, 2014), p. 72.

[45] T Ryle Dwyer, Tans Terror and Troubles, Kerry’s Real Fighting Story 1912-1923, pp289, 299, 305-307

[46] Carroll, Denis, They Have Fooled You Again: Michael O’Flanagan – Priest, Republican, Social Critic, (Dublin, 2016), p. 187.

[47] Carroll, Denis, They Have Fooled You Again: Michael O’Flanagan – Priest, Republican, Social Critic, (Dublin, 2016), pp 201 -3.

[48] Carroll, Denis, They Have Fooled You Again: Michael O’Flanagan – Priest, Republican, Social Critic, (Dublin, 2016), pp 244 -5.

[49] The Revolution Papers – Issue 1.

[50] Laffan, Michael, Judging W.T. Cosgrave, (Dublin, 2014), p. 71. W.T. Cosgrave obviously passed on this subservient ideological view to his son Liam Cosgrave who as Taoiseach in 1974 voted to help defeat his own government’s bill to legalise contraception on the grounds that “I am an Irishman second, I am a Catholic first and I accept without qualification in all respects the teachings of the Catholic Church”

[51] Terence de Vere White, “Kevin O’Higgins” (London 1948),

[52] Ryan, W.P., The Pope’s Green Island, (London, 1912)