‘Trampling the rights of a free people’: Coercion in Nineteenth Century Ireland

By John Dorney

According to the Republican historian Dorothy MacArdle, in the 19th century Ireland was governed, ‘almost continuously since the Act of Union’ by Coercion Acts, which ‘made every expression of national feeling a crime’.[1]

She quoted the Liberal politician Joseph Chamberlain, ‘it is a system founded on the bayonets of thirty thousand soldiers encamped permanently, as in a hostile country’.[2]

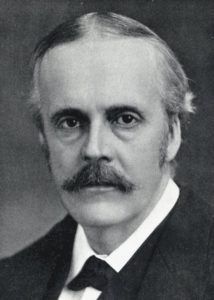

By contrast, American journalist, William Hurlbert, visiting in 1888 thought that the Irish nationalist complaints of ‘English tyranny’ were histrionic. He characterised the Chief Secretary, Arthur Balfour, nicknamed ‘Bloody Balfour’, as the ‘mildest mannered and most sensible despot who ever trampled the liberties of a free people’ and that ‘the rule of the [nationalist] Land League is the only coercion to which Ireland is subjected’. [3]

Normal civil liberties were suspended in nineteenth century Ireland far more often than in the rest of the United Kingdom.

However, it is a fact that for much of the 19th century, Ireland in theory now an integral part of the United Kingdom, saw basic civil liberties; the right not to be arrested without charge and the right to trial by jury, suspended for a prolonged period, in a way that they were not in England, Scotland or Wales.

The Insurrection Acts

In fact the use of emergency legislation dated back further than the Act of Union in 1800 to the Parliament of Ireland, which was dealing in the 1790s with United Irish insurrection.

The Insurrection Act of 1796, imposed the death penalty (replaced in 1807 by transportation for life) on persons administering illegal oaths – that is member of the United Irishmen or other secret societies such as the Defenders. Around 800 such prisoners were sent to the penal colonies in Australia, alongside many more ‘ordinary criminals’.

The Insurrection Act also allowed government to proclaim specific districts as ‘disturbed’, instituting a curfew, suspending trial by jury, and giving magistrates the authority to search houses without warrants and to arrest without charge. The act was in force throughout the revolutionary period of 1796-1802, and was reintroduced, in 1807-10, 1814-18, and 1822-5.[4]

According to James S. Donnelly’s figures, over 100 men were hanged and about 600 were transported to Australia under the Insurrection Act during the ‘Captain Rock’ agrarian rebellion of the early 1820s.[5]

Coercion Act 1833

The Coercion Act of 1833, formally Suppression of Disturbances Act (1833), the first under the Union, was mainly a response to the Tithe War disturbances of the 1830s – in which Catholic tenant farmers resisted paying compulsory tithes to the Protestant Church of Ireland. Essentially, it empowered the Lord Lieutenant to proclaim a district ‘disturbed’ and then to try suspects by military court martial, with penalties including death, whipping and transportation for life. [6]

It read;

In case the Lord-lieutenant should direct that any person charged with any offence contrary to any of the Acts aforesaid, which by law now is or may be punishable with death, shall be tried before any Court-martial appointed under this Act, such Court, in case of conviction, shall, instead of the punishment of death, sentence such convict to transportation for life, or for any period not less than seven years: and provided also, that such Courts shall in no case impose the penalty of whipping on any person convicted by or before such Courts: provided always, that it shall not be lawful for any such Court-martial to convict or try any person for any offence whatsoever committed at any time before the passing of this Act.[7]

The Coercion Act was enacted again the era of the Young Ireland rebellion in 1848-1849, and again in 1856. [8]

The Fenian era

From 1866 to 1869, habeas corpus, that is the right not to be arrested without charge, was suspended almost continuously in the face of the Fenian, or Irish Republican Brotherhood’s attempts at insurrection. The Fenians attempted to organise a nationwide military uprising in March 1867, with the aid of Irish veterans of the American Civil War.

In 1865, the British government suppressed the Fenian paper, The Irish People and arrested their leader James Stephens, and several hundred other activists (Stephens later escaped however). In 1866, habeus corpus, or normal, peacetime law, was suspended in Ireland under the Coercion Act.

Under the Coercion Acts, persons suspected of crime could be arrested and imprisoned without charge and sentenced to death or transportation or military courts.

According to an MP, Mr Labouchere;

It was well-known that in 1866–7 Ireland was in a state of almost open rebellion, there being then a strong case for the suspension of the Habeas Corpus Act. In February of that year, a Bill was brought in to suspend the Habeas Corpus Act, which was to continue to the 1st of September; and on the 10th of August it was extended until the expiration of 21 days after the commencement of the next Session of Parliament.[9]

The Conservative Spectator magazine approving wrote that,

‘the suspension of the Habeas Corpus was effectual, because it frightened the American Fenians out of the country. Lord Naas (afterwards Lord Mayo) himself gave this explanation of the operation of the measure,—” Numerous arrests were made, and persons who were known to be leaders of the movement were consigned to prison.”[10]

Many local Fenian groups were involved in agrarian agitation and attacks on landlords and agents as well as strictly nationalist activity. The suspension of Habeas Corpus acts was aimed at both nationalist and agrarian crime. The Quarterly review listed 17 murders of landlords, related to ‘Fenianism’ in 1869 alone. For this reason, the Fenian movement remained a threat to the political and social order long after its attempts at open rebellion in 1867 had failed.

Prime Minister Disraeli recorded of the last continuance act (extending the duration of the Coercion Act) in 1868,

14 February 1868, Lord Mayo tabled Habeus Corpus Suspension (Ireland) Continuance Bill, which he proposed should remain in effect until March 1869 and which he emphasised was ‘absolutely essential to the government’s efforts to frustrate and destroy the Fenian conspiracy’. [11]

The Spectator thought that no progress was made in eliminating what it called ‘agrarian crime’ until a new Coercion Act or ‘Peace Preservation Act’ was passed in 1870;

The Peace Preservation Act of 1870 could imprison witnesses to force them to testify.

‘This suspension [of habeas corpus], though it had its effect politically, had no effect at all on agrarian outrages. The greatest number of agrarian outrages was reported when the Suspension Act had already been in operation for eighteen months. The effect of the Suspension was political, and was nil in relation to agrarian crime. In 1869, the Suspension Act was allowed to expire ; but agrarian crime increased so much towards the end of 1869, that in 1870 the Peace Preservation Act was passed, which no doubt immediately reduced the number of outrages, and had; indeed, far more effect than any previous Act of this kind.[12]

The Peace Preservation Act allowed magistrates not only to detain suspects without trial, but also to detain suspected witnesses, to force them to give evidence against others and to hold them in prison until they testified.

However, if British, and particularly Conservative, observers, saw in the Coercion Acts merely a necessary response to crime, Irish nationalists even if they did not support the Fenians, saw it differently. An Irish MP Arthur O’Connor in 1881 recalled that in the 1860s normal civil liberties in Ireland had appeared to be suspended arbitrarily and without explanation.

The right hon. Gentleman also said that the Bill was to protect life and property in Ireland; but he forgot altogether the manner of that protection. It really was a Bill to suspend all law in Ireland. There would be no law in that country except the arbitrary will of the Lord Lieutenant. There would be no liberty of the person. Men and women at any time might be arrested on suspicion of having committed crime, or of having aroused the suspicion of the authorities at Dublin Castle and their spies. There would be no liberty of speech, for no speaker could tell what interpretation would be placed upon his words by some irresponsible person.[13]

No Fenians were executed under the Coercion Act (three were however hanged for murder in Manchester) but several thousand were imprisoned and others were transported to penal servitude in Australia.

The Land War

Two more Coercion Acts followed in the era of the Land War (in 1881 and again in 1887). This was a period in which the Land League, led by Irish nationalists Michael Davitt and Charles Stuart Parnell, among others, attempted first to halt evictions and to lower rents at a time of world economic recession.

The main weapons of the Land League were the ‘boycott’ or social ostracism, as well as rent strikes, and other methods of passive resistance. However, as in the past, agrarian strife was also punctuated by assassination of landlords and agents.

Violence peaked in 1880-1882 as landlords attempted to recover the rent arrears of the previous year and to evict those who would not or could not pay rent. In 1880, 2,585 ‘outrages’ were reported, in 1881, 4439 and in 1882, 3433. These included an average of 17 murders per year of landlords and their associates, though much more common were acts such as intimidation and cattle maiming.[14]

There were two Coercion Acts during the years of land agitation in 1881 and 1887, during which leaders such as Davitt and Parnell were imprisoned

Evictions, which were enforced by bailiffs under the protection of the police and military, also spiralled. There were in total 11,215 evictions during the Land War. [15]

The government on 1 January 1881 introduced a Coercion Act, becoming law in March of that year. It was essentially in line with the earlier Coercion Acts , suspending habeas corpus, trial by jury and facilitating the proclamation of entire districts as ‘disturbed’. Irish nationalists were dismayed that it had been enacted by their hitherto allies, the Liberals, rather than their customary opponents, the Conservatives.

Over 950 people were imprisoned under the Act, including Land League leader Michael Davitt in February 1881. Parnell and his party were ejected from House of Commons in February 1881 for protesting Davitt’s arrest.[16]

The Prime Minister Gladstone tried to pacify Ireland by introducing a Land Act that would set up arbitration boards which would determine a ‘fair rent’. In September 1881 Parnell urged his followers to ‘test’ the Land Act by trying arbitration boards, convincing Gladstone that he was trying to undermine the Land Act. He was arrested on 20 October 1881, for ‘inciting tenants not to pay rent’ and imprisoned in Kilmainham Goal, in Dublin. [17] From prison, Parnell issued a ‘no-rent manifesto’, urging no tenants to pay rent, for which the Land League as a whole was declared illegal under the Coercion Act. [18]

The arrest of Parnell and his associates and the banning of the League did little to reduce disturbances however. Much of the organising was taken up the Ladies’ Land League, led by Parnell’s sister Anna, who sustained the land agitation over the following six months.

Parnell was finally released in April 1882 after a deal termed ‘the Kilmainham Treaty’ in which he agreed to revoke the no-rent manifesto. In return Gladstone promised to wipe out arrears in rent owed by many of Parnell’s followers and to gradually drop coercion. The hard-line Chief Secretary for Ireland William Forster had resigned in protest at Parnell’s release.

This compromise was not helped by the subsequent assassination of the two highest ranking British officials in Ireland in the Phoenix Park murders of May 1882, in which Forster’s replacement, Frederick Cavendish and the Under Secretary, Henry Burke were stabbed to death by a Fenian splinter group named the Invincibles.[19]

Nevertheless, the Kilmainham deal gradually defused the conflict on the land. Agrarian ‘outrages’ largely ceased by the end of 1882 and the Coercion Act was allowed to lapse[20]

However, it was revived after another burst of land agitation; the ‘Plan of Campaign’ led by nationalist activists William O’Brien and Michael Davitt in 1886. This again was mainly a campaign of ‘moral force’ involving rent strikes and boycotts, but also, again, considerable violence against landlords, agents and ‘land grabbers’.

The British government, now under the Conservative Prime Minister, Lord Salisbury, in 1887 passed another Coercion Act under which suspects could be imprisoned by a magistrate without a trial by jury and ‘dangerous’ associations, such as the National League (as the Land League was renamed in late 1882), could be prohibited.

The legislation was prompted, in part, after The Times of London published its sensational “Parnellism and Crime” series, which sought to link to the Irish Parliamentary Party leader to the 1882 Phoenix Park murders.[21]

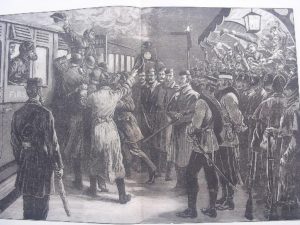

The 1887 Coercion Act was particularly associated with the Chief Secretary Arthur Balfour, Police opened fire on a crowd of protesters at Mitchelstown County Cork, at a prohibited meeting, in 1887, killing three, in an event known as the ‘Mitchelstown massacre’ among Irish nationalists and earning Balfour the title ‘Bloody Balfour’.[22]

The Coercion Acts were never repealed.

Balfour had come into office promising ‘repression as stern as Cromwell’s.’ And though, among contemporary Irish nationalists at least, he became an equivalent hate figure to the 17th century Lord Protector, historian Joe Lee remarks that, ‘his “repression” resulted in little more than William O’Brien losing his pants in jail and three people losing their lives in Mitchelstown…a derisory haul that would have left Cromwell turning in his desecrated grave’.[23]

Though Balfour was a staunch opponent of Irish self-government, he was not wholly unsympathetic to Irish grievances. Indeed British rule in Ireland from the 1880s onwards was characterised by concession as well as repression, a policy that included extending the powers of local government, land reform and encouraging economic development, known colloquially as ‘killing Home Rule with kindness’.

Restoration of Order

And yet, in no other part of the United Kingdom was normal peacetime law so regularly suspended as it was in Ireland. The Coercion Acts were never repealed, despite regular nationalist attempts to bring up the matter in Parliament. In 1908, one such attempt made it to the Committee stage at Westminster but went no further.

When in 1920, Britain was again facing a significant challenge to its rule in Ireland it again resorted to military courts, internment without trial and official reprisals in the Restoration of Order in Ireland Act.

One senior British politician, Lord Riddell, noted after meeting the Prime Minister Lloyd George in October 1920 that, ‘I came away with the conclusion that this was an organised movement [of reprisals] to which the Government are more or less assenting parties.’ Lloyd George, apparently would have preferred if troops and police had confined themselves to shooting ‘Sinn Feiners’ rather than burning property, but felt that reprisals ‘ had, from time immemorial, been resorted to in difficult times in Ireland… where they had been effective in checking crime’.[24]

It was perhaps ultimately as one British politician Lord Morley stated, Coercion was ‘the best machine ever devised for governing a country against its will’. [25]

References

[1] Dorothy MacArdle, The Irish Republic (1968), p.46

[2] Ibid. p.49

[3] Mark Holan, 1888: An American Journalist meets Arthur Balfour and Michael Davitt. https://www.theirishstory.com/2018/09/13/1888-an-american-journalist-in-ireland-meets-michael-davitt-arthur-balfour/#.XMLy0th7nIU

[4] http://members.pcug.org.au/~ppmay/acts/insurrection_acts.htm

[5] James S Donnelly, Captain Rock, The Irish Agrarian Rebellion of 1821-24, p.323.

[6] The details of the 1833 Act are here.

[7] https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/lords/1833/apr/01/suppression-of-disturbances-ireland

[8] [Mr W Holms on history of Coercion acts in Ireland].

[9] https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1881/feb/21/protection-of-person-and-property-1#column_1421

[10] The Spectator 1880 25 December p.6

[11] Disraeli papers 4728 here

[12] The Spectator 1880 25 December p.6

[13] https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1881/feb/21/protection-of-person-and-property-1#column_1421

[14] James H. Murphy, Ireland, A Social, Cultural and Literary History, 1791-1891 p.128

[15] Murphy p.125

[16] Joseph Lee, The Modernisation of Irish Society 1848-1918 p.87

[17] Lee p87-88

[18] https://www.encyclopedia.com/international/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/land-war-1879-1882

[19] Shane Kenna, The Phoenix Park Killings, https://www.theirishstory.com/2012/07/31/the-invincibles-and-the-phoenix-park-killings-2/#.XMMHCNh7nIV

[20] Lee p.91

[21] Mark Holan, https://www.theirishstory.com/2018/09/13/1888-an-american-journalist-in-ireland-meets-michael-davitt-arthur-balfour/#.XFyFYqDgrIV

[22] Murphy p 132

[23] Lee, p.126

[24] or Lloyd George’s view of ‘unofficial reprisals’ see Michael Hopkinson, The Irish War of Independence p. 82 and for official Reprisals, ibid. p.93

[25] MacArdle, The Irish Republic, p.49.