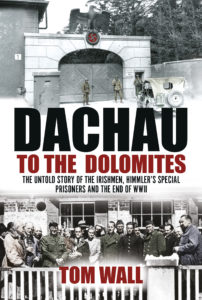

Book Review: Dachau to Dolomites: The Irishmen, Himmler’s Special Prisoners and the End of WWII

By Tom Wall

By Tom Wall

Published by Merrion Press, 2019

Reviewer: Daniel Murray

If, in popular culture, the POW experience from World War II is the movie The Great Escape, then this book could be considered its antithesis. Instead of the daring-do of an irrepressible Steve McQueen as he clears a barbed-wire fence on a motorbike, we have here men and women doing their best simply to endure. Not all succeeded, and the fate of Yakov Dzhugashvili – the captured son of Joseph Stalin – was a case in point about how a sentry’s bullet did not play favourites:

He put one leg through the trip-wire, crossed over the neutral zone and put one foot into the barbed wire entanglement. At the same time he grabbed an insular with his left hand. Then he got out of it and grabbed the electrified fence. He stood for a moment with his right leg back and his chest puffed out and shouted at me ‘Guard, don’t be a coward, shoot me!’

The German guard in question duly did so. “A shot rang out, followed by a blinding flash, and poor Jakob [sic] hung there, his body horribly burnt and twisted,” recalled another witness, ‘Sergeant’ Thomas Cushing. He left out the small detail that the luckless man had been outside their shared hut in the first place because he, Cushing, chased him with a knife after a brawl broke out between the Russian and Irish prisoners.

But then, Cushing was a slippery individual. German military intelligence in the form of the Abwehr were interested in the recruitment potential of Irish-born POWs from the British Army, and Cushing was among those receptive to what his captors had to offer – or, at least, was willing to let them think so.

One could never quite tell with someone like Cushing, who claimed membership in the IRA during the Irish War of Independence (when he would have been ten), fought on the Republican side in the Spanish Civil War (doubtful) and claimed the rank of sergeant while in Friesack Camp (he wasn’t). A chaplain at Friesack probably had the measure of the man when he described Cushing as someone who would “do and say anything to get out of prison.”

An equally crafty – though perhaps more admirable – Irishman in the camp was Colonel John McGrath, who also volunteered his services. In his case, he did so to undermine the German operations from within. When opportunity came in the form of a visiting priest (and a fellow son of Erin), Father Thomas O’Shaughnessy, McGrath had a list of the names of other inmates being trained by the Abwehr for sabotage missions smuggled out on the person of the padre at, as it turned out, no small cost to himself.

The subtitle here is somewhat misleading, as Irishmen like McGrath and Cushing are merely one of the many nationalities present in this book who found themselves at the mercy of the Third Reich, though McGrath fits the role of central character best of all; appropriately enough, given that it was the sighting of his name, in an unexpected place, which inspired historian Tom Wall:

At the entrance to the exhibition in the Dachau Concentration Camp Memorial Site, there is a large wall map listing the names of prisoners from each country held in that notorious place. A figure of ‘1’ is superimposed on a map of Ireland. On a visit, intrigued by who this fellow Irishman might be, I began a journey of discovery. I soon learned he was John McGrath, from Elphin in Country Roscommon.

McGrath’s undercover work came with painful consequences. The Abwehr caught wind of his leakage, not through Father O’Shaughnessy – who was as good as his word in taking the information brief, first to London and then to the Irish Government – but when a coded message to Dublin was broken.

After some “intensified interrogation”, with the threat of execution as a spy, McGrath spent ten months in solitary confinement before being transferred to Dachau, where he became part of a group of around 160 prisoners, representing 18 European countries – the Prominenten – gathered for use as bargaining chips by high-ranking Nazis desperate to save their own skins as the war turned against them.

While this gave the Prominenten value, one of them, the former French statesman, Léon Blum, was all too aware of the perilous situation this status put them in, as he noted in his diary:

When you say: ‘I offer to exchange Mr. so and so, who is in my hands, for this other,’ it necessarily means: ‘if you refuse to bargain, I will do away with Mr. so and so.

Blum had good reason to worry; in post-War trials of high-ranking Nazis, plans for Operation Volkenbrand – Fire Cloud – emerged, where the Luftwaffe was to bomb Dachau out of existence. Alternatively, its residents could be shot or poisoned. “Shoot them all! Shoot them all!” Hitler ranted during a conversation in his bunker where the Prominenten were among the topics, though it was debatable as to which of his many enemies the unhinged Fuhrer was referring to.

Finally, it was decided by the authorities to evacuate Dachau. The Prominenten at least left by bus, a relative luxury compared to how the ordinary prisoners were forced to march on foot, a sign of the importance that the German high command placed on them. A good character reference on a witness stand after the War could make all the difference in a war crimes court, after all.

Even then, there was no guarantee of survival for the hostages as they were taken southwards, their intended destination being the Alpine fortress where the regime was expected to make its last stand. Their SS guards might keep them alive – or just as easily kill them to avoid any inconvenient finger-pointing later. One German assured a British POW, with whom he had become friendly, if not quite friends, that he would give him, if needs be, a clean end, via Nackenschuss – a pistol shot to the back of the head – of which he was an expert.

It was intended as a favour. Perhaps it was. It was hard to be sure in a nightmarishly uncertain world, where clear concepts held less and less meaning. Even ‘captor’ and ‘captive’ were becoming blurred, as it was suggested to the former that they relinquish command to the latter. This was while an attack by anti-Nazi partisans was being planned with the knowledge of some of the prisoners, and to the alarm of the others who feared being caught in the crossfire just when the end of the fighting was in sight.

Despite the setting, this is less of a war book and more of a study of human nature. Considering the range of personalities and situations, it can be a difficult book to take in at one go and rereads might be needed to fully grasp some of the nuances.

Everything, from the inner workings of Reich politics to the ethnic tensions between Germans and Italians in South Tyrol – where the Prominenten and their escorts ended up – is grist to the mill here, but especially the different ways individuals, whether heroes, villains and everything in between, will respond when pushed to extremes.

Some just give up, such as poor Dzhugashvili. Others rise to the occasion as best they can, like McGrath. But liberty for those who survived brought challenges of a different, more insidious sort. McGrath returned to his former managerial job in the Theatre Royal in Dublin but soon resigned due to nerves unhealed from his time as a prisoner. When he died, just seventeen months after his homecoming, it was Father O’Shaughnessy, appropriately enough, who delivered the last rites. Those wanting a Second World War book of a different sort, stripped of the usual heroics, would be well recommended to try this one.