A Civil War as a sort of side-show? Partisan politics in the Irish Free State and the Eucharistic Congress of 1932

Barry Sheppard on a moment in Irish history when national and religious identity appeared mired in political conflict.

In 1932 Dublin was chosen as the venue for the 31st International Eucharistic Congress, the largest international gathering of Catholics in the world. With the celebrations to be held in June of 1932, it came at a sensitive time in Irish political and social life. A mere decade into the Irish Free State’s existence, it would bring a spotlight down on Irish society for the first time since the State was granted independence from Britain.

Ireland had been chosen as the venue for the Congress to commemorate the 1,500th anniversary of St. Patrick’s arrival in Ireland; a significant marker when one considers that this was well before the assumed date of colonisation by England. The event represented a return to the spiritual and cultural values which leading political and societal figures on both sides of the Treaty divide wished to project as authentic Irishness. Of course, this projected image of unity of purpose masked very real tensions among the political elites and the other strata of Irish society.

The scars of civil war were still raw, and the rise of Fianna Fáil, the anti-treaty party, brought with it real fears that the civil war could soon reignite. Fianna Fáil was unhappy with many of the aspects of the Treaty, and threatened to dismantle them. This raised tensions between the rising Fianna Fáil party, and the ruling Cumann na nGaedheal administration, and brought with it the expectation that these tensions would erupt at the very time the State would be making a positive mark on the world stage.

‘How will you vote? A Matter of Vital Concern to everybody’.

This was a question posed by John. P. Scanlon in the Sligo Champion on 30th January 1932, the day after the previous Dáil had been dissolved. The concern arose from the election which had just been called. For Scanlon there were a number of reasons to be concerned. Globally, it was a time of ‘acute economic and financial depression’.

This climate of uncertainty had given rise to populist movements in a variety of countries, many of which peddled the doctrine of ‘Godless patriotism’. There was a fear, that this populism in the Free State, in the form of Fianna Fáil could make political capital of the worldwide conditions. Any such victory could potentially undo the stability which had gradually been achieved over the course of the previous decade.

The rise of Fianna Fáil over the previous number of years had begun to eat into Cumann na nGaedheal’s electoral dominance since the treaty was ratified. Eamon de Valera and co had been closing in on Cumann na nGaedheal, especially in the two previous elections held in 1927. Now in 1932 the election was being called ‘the most important that has been held in the 26 counties since the passing of the Treaty’.[1]

The uncertainty which the rise of Fianna Fáil had carried with it gave advocates for Cumann na nGaedheal, like Scanlon many headaches. He viewed Cosgrave’s party as ‘tried and true’, and conversely de Valera’s upstarts as ‘untried and false’.[2] Yet, it wasn’t the latter party’s untested skills in navigating the ‘acute economic and financial’ climate which troubled Scanlon and others.

Critics had been troubled by the constitutional position of Fianna Fáil. Since they were founded in March 1926, they had been a thorn in the side of the established Cumann na nGaedheal party, with some commentators suggesting they engaged in ‘no constructive work’, with all their energies ‘directed against destructive criticism’ of the Government.[3]

Their mission to dismantle the Treaty sat uneasy with their political opponents, some of whom feared a return to the violence of earlier in the decade. The much-quoted 1928 Dáil utterance by Sean Lemass saw him brand Fianna Fáil as a ‘slightly constitutional party’. This was naturally seized upon by political opponents as evidence that the party had not left behind their militant republicanism. Indeed, this soon to become infamous statement was viewed as a warning right across the house. Labour TD for Cork West Timothy J. Murphy described the utterance a short time later as ‘a sinister and significant statement’.[4]

The prospect of Fianna Fail, political heirs of the anti Treaty faction of the Civil War, winning the 1932 election frightened many pro-Treaty supporters.

According to some, Fianna Fáil had ‘married militant language with moderate actions’ in such a way that it convinced its militant supporters ‘the only effective way to challenge the Free State was not by a frontal assault from without but, like a republican Trojan horse’ from within.[5]

Not only did the party bring its more militant support-base with it on this new phase, the at times ambiguous rhetoric employed by Fianna Fáil confused their political rivals to the point that it seemed a re-entry into violent confrontations was inevitable.

This was picked up on in Scanlon’s plea in the Sligo Champion, who argued that part of their ‘falseness’ derived from their pledge ‘to disrupt the State by seeking to throw over the Treaty’. Scanlon marked the pre-election battle lines by stating that ‘Cumann na nGaedheal has built up the Irish State. Fianna Fáil has endeavoured to smash it to pieces’.

These sentiments are familiar to those who have studied the period, yet for Scanlon the extra tragedy of this seemingly inevitable trajectory towards violence was that it would unfold in front of the eyes of the world’s most influential Catholics. The upcoming election of life and death proportions was being held ‘on the eve’ of the Eucharistic Congress, the significance of which, he argued was lost on much of the public.[6]

The Eucharistic Congress

The power of the Congress to shape Catholic opinion on a global basis was perhaps, as Scanlon alluded to, unknown to the public at large. A previous Congress, held in Sydney in 1928 was heralded in the Australian media as ‘that great epoch in the world’s Catholic history’.[7]

The magnitude of such an event was well-known to those who had already hosted it, and no event on this scale and with this much international attention had been staged in Ireland before. Indeed, Gerry Kane states that ‘the Congress put Dublin on the international map’.[8] The spectre of a new civil war at a time when such attention would be focused on Dublin and the rest of the country would damage not only the fragile State, but its standing in the international community. According to Scanlon

‘The eyes of the world are upon us to see what we shall do, and when that Government is placed in power it will be subjected to the severest test of any on earth in so much as those who will come to attend the Congress – the leaders of Catholic thought throughout the world – will be here to observe. And that observation will be intelligent, informed and in many cases expert. It is pretty safe to say that our standing as a World State will depend for many years to come, if not for good, on the impression our rulers make on those visitors to our shores’.[9]

The Free State, as a recently created state, still sought international acceptance, and wished to build upon positions of international standing that it had already achieved in the previous decade. The state was at that stage an ‘internationally-recognized political entity with a seat at the League of Nations’.[10]

Hosting the Eucharistic Congress, along with the Free State’s gaining a seat at the League of Nations, was a sign of international recognition.

Such a prestigious accolade for a State not a decade old would undoubtedly be tainted if violence was to occur while foreign representatives of numerous countries were in the line of fire. Kane argues that violence was a reality in the State at the time, and that ‘any group contemplating a congress of people, national or international, would have to take these contemporary realities of Irish public life on board’.[11]

Further to this, it is perhaps obvious to say that the potential for violent political upheaval was contrary to everything to Congress stood for, which was ‘the best means to spread its knowledge and love throughout the world’.[12]

The ‘leaders of Catholic thought throughout the world’ were especially revered and courted by leaders of the State. The Congress was being hosted only three years after the State had established diplomatic links with the Holy See in 1929. Diplomatic links had previously been attempted by Sean T. O’Kelly in 1920, when he approached Pope Benedict XV.

Highlighting Ireland’s long-standing adherence to the Catholic faith, O’Kelly argued ‘Ireland’s righteous and time-honoured claims have been frequently recognised by Your Holiness’s Predecessors and even actively assisted by them as far back as the sixteenth century’. (Memorandum by Sean T. O’Kelly to Pope Benedict XV, 18 May 1920 – Ref: No. 35 NAI DFA ES Paris 1920). This plea, which evoked long-standing history, and religious aspI.R.A.tions fell on deaf ears.

The establishment of diplomatic links in 1929 was, of course arranged to coincide with the centenary of Catholic Emancipation, passed in 1829. A move which Cumann na nGaedheal’s Patrick McGilligan stated at the time, was ‘a source of very great satisfaction, not only to the Irish People here in this country, but also to the millions of our race all over the world’.[13] Fianna Fáil, however were somewhat opposed to the move. De Valera had privately believed at the time that the Vatican was pro-British.[14]

Indeed, during the speech on widening diplomatic relations, including that with the Holy See, Patrick McGilligan accused Sean T. O’Kelly and de Valera of ‘creating mischief’ in frustrating attempts to open relations with the Vatican.[15]

Such political manoeuvrings didn’t go unnoticed and allowed political opponents and attuned members of the public to portray Fianna Fáil as anti-clerical and against the new identity of the State. It has been noted that there were a number of concerns about the character of de Valera, which extended even to the Vatican at this time, with negative impressions lasting up until his election victory just before the Congress was hosted.[16]

Constitutional Amendment 17

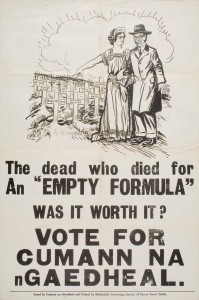

The threat of renewed civil war was never too far below the surface in political discourse, and ‘Civil War’ jibes had been exchanged a number of times across the benches of the Dáil since Fianna Fáil dealt with the ‘empty formula’ conundrum, and entered the political mainstream.

Nevertheless, the ante was upped in October of 1931, with the introduction of Constitutional Amendment No 17, more commonly referred to as the Public Safety Act 1931. Tensions had already been high in the wake of the assassination of Kevin O’Higgins on 10 July 1927.

This resulted in the 1927 Public Safety Act, which allowed for the suppression of seditious newspapers, and trial by court martial, as well as internment, among other measures.[17] Although this act had lapsed in December 1928, it by no means dealt with the issue of illegal organisations, nor assuaged fears of renewed civil war.

In 1931 the Free State government introduced emergency legislation designed to thwart a feared IRA insurrection. Some thought it was to guarantee order during the Eucharistic Congress.

The introduction of the 1931 Act was wide-ranging and allowed for ‘the trial by military tribunal of certain scheduled offences, such as membership of an unlawful organisation, possession of documents relating to an unlawful organisation, refusing to answer questions, unlawful possession of firearms, unlawful assembly, contempt of tribunal, intimidation, refusing to account for one’s movements, and so on.’[18]

An internal memo from Eoin O’Duffy on proposing the constitutional amendment stated that he ‘lamented the effect on the public of Fianna Fáil’s criticism of state institutions and their promise of change if they were brought to power’.[19] It’s clear that although the I.R.A. were responsible for the outrages which forced Cumann na nGaedheal into action, Fianna Fáil’s rhetoric was viewed as giving political legitimacy to such activities, and created discontent among swathes of the public.

During a feisty debate on the finances of the 1931 Act, Deputy McGilligan and Sean Lemass traded barbs over the introduction of the Act, with Lemass arguing that his party were collateral damage in Cumann na nGaedheal’s dangerous game. He suggested that the Government were attempting to squeeze Fianna Fáil in between ‘the hammer of Cumann na nGaedheal and the anvil of the I.R.A.’.

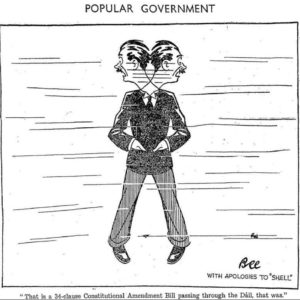

Furthermore he stated the Act was nothing to do with peace and stability, and that the Executive Council ‘coldly and calmly sat down and decided to provoke a civil war (with the introduction of the Act) now for some particular reason’. Asking ‘what was the reason?’ of introducing the Act, Deputy Seán Brady of Fianna Fáil interjected, exclaiming dramatically, ‘The Eucharistic Congress’!

In a measured response to this, Lemass addressed the chamber and stated that the Public Safety Act was introduced for electoral gain, and that ‘no one could contemplate the Government deciding to start a civil war as a sort of side-show (to the Congress)’.[20] Regardless of the Government’s true intentions, it was apparent that concerns around the Eucharistic Congress as a backdrop to civil war had permeated mainstream politics. [21]

Further to this, there were those who thought that going down the path of coercion was counterproductive, especially with an event the scale and prestige of the Congress just over the horizon.

Further to this, there were those who thought that going down the path of coercion was counterproductive, especially with an event the scale and prestige of the Congress just over the horizon.

At a special meeting of Kilkenny Co. Council on 20th October 1931, a resolution was passed ‘protesting in the strongest manner possible’ against “the new Coercion Act” which had just been passed through the Dáil.

Members proposing the resolution were convinced that those ‘who dictated the policy of coercion to the Government had not the best interests of the country at heart and were determined, even at the arrival of the Eucharistic Congress to destroy the goodwill and harmony at present prevailing’.[22]

Cosgrave’s efforts throughout the summer of 1931 in ‘assiduously cultivating’ the Catholic hierarchy in ‘securing its endorsement of the planned anti-republican crusade’[2], paid some dividends. Irish Bishops gave qualified support to the Public Safety Act. Nevertheless, wholehearted endorsement was not forthcoming.

In truth, it was known by the clergy that ‘the I.R.A. was not particularly anti-clerical, while Fianna Fáil and Sinn Fein were clericalist in outlook’. Further to this there was a reluctance among the Catholic Church in Ireland to publicly denounce the I.R.A., as they had done in 1922, as this had alienated many of the State’s Catholics.[3] Nevertheless, the image of an anti-clerical Fianna Fáil persisted in some quarters.

Letters

The concerns of civil conflict which were being felt at a political level, naturally filtered down to the person in the street, and were reflected in the letters pages of a variety of newspapers. The fear of an escalation of violence was voiced in the pages of the Irish Press in October 1931. Unease over the proposed Act was voiced, proclaiming that it was an affront to Ireland’s people, and threatened ‘to make a mild disorder a violent distemper’.

The unravelling of a fragile situation was made all the more pressing with the potential that it could happen in full view of visitors and Catholic coreligionists from all parts of the globe. The letter continued “the Eucharistic Congress will soon be upon us. Let us see to it that it does not find us with thousands of our young people in jail and the stage setting towards civil war. What a spectacle that would be for the Catholic world”![23]

In the wake of the Public Safety Act, trepidation grew as to how the Act would reopen recent wounds. An Australian letter to the Fermanagh Herald lamented that the spectre of civil war now stalked the Irish countryside yet again, so soon after the previous tragic episode. The exile’s letter read:

“As I pen these lines, the cable reports from my native land bring news of further signs of political troubles. With all my heart I hope that the dreadful tragedy of civil war will not again darken the pages of Irish history. The Year 1932 is going to be a great year for Ireland. Irishmen from all over the world will return to their native land to see the King of Kings honoured in the great ceremonies of the Eucharistic Congress. It would be a sad homecoming to find on arrival in Ireland the young men of the country at grips with the law”.[24]

“With all my heart I hope that the dreadful tragedy of civil war will not again darken the pages of Irish history”

Another letter of note in the Irish Examiner on 16 February, 1932 from ‘A Farmer’s Son’ after the election had been announced, contained similar fears, and implored the electorate to stick with Cosgrave’s administration in the face of mounting political turmoil:

‘Sir, At the moment the Free State electors are on their trial as between upholding the Treaty or plunging our country again into the cauldron of chaos, disturbances, devastation, and civil war, as well as having at large the “gun bully”, murderer, burner, and highway robber. In God’s name, this holy year, let voters (men and women) go out and vote for the Cosgrave Government, the only party that we can trust to give us peace and order when the great Eucharistic Congress comes to Dublin’.[25]

The choice before ‘the Farmer’s Son’ was clear, stability or chaos, with the ‘gun bully’ emboldened in front of the eyes of the Catholic world. Outside of the immediate threat of Civil War, the letter deliberately ties Fianna Fáil in with other ‘anti-God societies’, before asking the electorate to place their vote with the ‘Christian (no Soviet)’ Edmond Carey in Cork East as their ‘good Catholic member’.[26] The plea fell on deaf ears, as Carey lost his seat, never again to be re-elected before his death some years later.

Conclusion

There proved to be nothing of the predicted upheaval which was expected to accompany the coronation of de Valera. The threat of a coup d’état by Eoin O’Duffy and other disaffected treatyites never materialised. O’Duffy’s relationship with Cumann na nGaedheal had reached breaking point. He regarded Fianna Fáil as unfit to govern, and subversive, and had little faith in the Cumann na nGaedheal government which was stagnant and ready to be dethroned. He canvassed support among senior Special Branch officials on the potential for a coup.[4]

It has been often remarked that the Eucharistic Congress helped to mask the bitterness of post-Civil War Ireland.

Despite O’Duffy’s position, the Government changed from Cumann na nGaedheal to Fianna Fáil with relatively little fuss. Nevertheless, concerns over illegal drilling by the I.R.A. prevailed, and was linked to how it would be viewed in relation to the Eucharistic Congress. A political row developed over the supposed drilling of the I.R.A. in May of 1932, a number of weeks before the Congress was due to begin. Fianna Fáil TD for Donegal, Frank Carney accused Cumann na nGaedheal of fabricating I.R.A. arms dumps to discredit the new ruling party.

Carney accused Cumann na nGaedheal of attempting to ‘broadcast to the world that illegal drilling is taking place, and that in every back yard and every field there is a dump’. He went on to exclaim that ‘this is tantamount to saying to visitors who may think of coming here during the Eucharistic Congress: “Ireland is a safe place to stay out of”.[27]

It has been often remarked that the Eucharistic Congress helped to mask the bitterness of post-Civil War Ireland. Diarmaid Ferriter states that the groups involved in organising and working at the Congress, who came from various political viewpoints, felt uneasy in each other’s company. This persisted until Éamon de Valera broke the tension by inviting the officer in charge to sit at his side during the meal, a reminder that the congress served a number of different purposes’.[28]

The event was a unifier, and laid down a marker for the character of the State for decades to come. Indeed, the event was looked back upon with pride, and as a defining moment in the State’s history. However, what is notable is how the event was used by political parties to highlight the possibility of renewed civil war.

It was the first time the eyes of the world had been on the independent state, and this attention made some politicians uncomfortable, due to the combustible politics of the State, fed by the unanswered questions around the civil war and Treaty.

Those in the public who knew of the potential the Congress brought with it voiced frustrations that a slide backwards to renewed and futile conflict would rob them not only of their immediate future, but their world standing. The powerful symbol of the Congress was for a time both longed for, to show Ireland’s potential, and feared, that it would see too much of what was left to do.

References

[2] Donnacha Ó Beacháin, Destiny of the Soldiers: Fianna Fáil, Irish Republicanism and the I.R.A., 1926–1973, pp. 119-120

[3] Fearghal McGarry, Eoin O’Duffy: A Self-Made Hero, p. 184.

[4] Fearghal McGarry, Violence, citizenship and virility: The making of an Irish fascist, History Ireland, Issue 6 (Nov/Dec 2005), Vol. 13

[1] Sligo Champion, 30 Jan. 1932.

[2] Ibid, p. 8.

[3] Nenagh Guardian, 30 Jan. 1932.

[4] Dáil Eireann Debate – 2 May 1928.

[5] DONNACHA Ó BEACHÁIN ‘Slightly Constitutional’ Politics: Fianna Fáil’s Tortuous Entry to the Irish Parliament, 1926–7, Parliamentary History, Vol. 29, pt. 3 (2010), pp. 376–394

[6] Sligo Champion, 30 Jan. 1932.

[7] The Forbes Advocate, 28 Aug. 1928.

[8] Gerry Kane, ‘The Eucharistic Congress of 1932’ in The Furrow, Vol. 58, No. 6 (Jun., 2007), pp. 343-346

[9] Sligo Champion, 30 Jan. 1932.

[10] DONNACHA Ó BEACHÁIN ‘Slightly Constitutional’ Politics: Fianna Fáil’s Tortuous Entry to the Irish Parliament, 1926–7, Parliamentary History, Vol. 29, pt. 3 (2010), pp. 376–394.

[11] Gerry Kane, ‘The Eucharistic Congress of 1932’ in The Furrow, Vol. 58, No. 6 (Jun., 2007), pp. 343-346

[12] The Catholic Encyclopaedia 1910.

[13] Dáil Eireann Debate – Wednesday 5 June, 1929.

[14] ‘Kenny’s speech historic and unprecedented in publicly calling Holy See to book’ Irish Times, 22 Jul. 2011

[15] Dáil Eireann Debate – Wednesday 5 June, 1929.

[16] Rory O’Dwyer, On Show to the World: The Eucharistic Congress, 1932, in History Ireland, Vol. 15, No. 6 (Nov. – Dec., 2007), pp. 42-47

[17] Public Safety Act, 1927. http://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/1927/act/31/enacted/en/html

[18] Bill Kissane, ‘Defending Democracy? The Legislative Response to Political Extremism in the Irish Free State, 1922-39’ in Irish Historical Studies, Vol. 34, No. 134 (Nov., 2004), pp. 156-174

[19] Ibid.

[20] Dáil Eireann Debate, 15 Oct. 1931 – Committee on Finance – Constitution (Amendment No. 17) Bill, 1931 – Money Resolution

[21] ‘Popular Government’ Irish Press 19 October 1931.

Refers to Cumann na nGaedheal’s rushing through of the Constitutional Amendment (17) Act of October 1931.

[22] Irish Press, 21 Oct. 1931.

[23] Irish Press, 15 Oct. 1931.

[24] Fermanagh Herald, 5 Dec. 1931.

[25] Irish Examiner, 16 Feb. 1932.

[26] Irish Examiner, 16 Feb. 1932.

[27] Dáil Eireann Debates – 20 April 1932.

[28] Irish Times, 23 June, 2007.