Michael Collins, Northern Ireland and the Northern Offensive, May 1922

By Patrick Concannon

As we enter the next few years of commemoration they will be dominated by huge historical events like the Government of Ireland Act which partitioned Ireland and set up the Northern Ireland state, the War of Independence- a bloody and clandestine conflict which led to the deaths of around 1800 people and the Irish Civil war which set brother against brother costing the lives of 1500-2000. [1] In the midst of all this will be an anniversary which will pass with little fanfare and even less public awareness

The Northern Offensive of May 1922 was Michael Collins’ plan to end partition.

That event was known as the ‘Northern Offensive’ and is still so shrouded in mystery and intrigue that it is difficult to unravel. Its instigator was none other than the Provisional Government leader and (from June 1922) National Army Commander in Chief, Michael Collins. He enlisted the help of the anti-Treaty IRA and its leader Liam Lynch in these endeavours.

This offensive; the culmination of a series of complex events; ended in the complete failure of the operation and the eventual defeat of the Northern IRA.

Background

The seeds of the offensive lie in fallout from the Anglo-Irish Treaty, which split the Republican movement in two. The Dail, on 7th January 1922 passed the Treaty by 64 votes to 57, essentially dissolving the Republic declared in 1919.

Almost immediately after the Treaty was accepted, Michael Collins began recruiting from Pro-treaty IRA units to form the National Army of the Provisional Government. The heads of that Government were to be Arthur Griffith and Michael Collins.

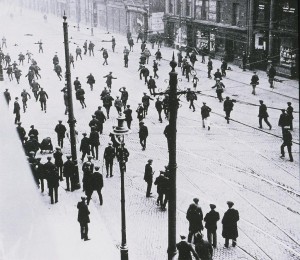

In the meantime the violence in Northern Ireland began to increase as partition became permanent and security powers had been transferred to the Northern Ireland government. As Roger McCorley IRA Commander in Belfast stated sardonically in his Bureau of Military History statement, “the truce in Belfast lasted 6 hours, the pogroms lasted two years”. [2]

“The truce in Belfast lasted 6 hours, the pogroms lasted two years”. Roger McCorley

In the midst of this continued conflict in the north, Michael Collins and Sir James Craig met in London in an attempt to find some sort of solution to the violence. Thousands of Catholics had been evicted from their jobs at the Shipyards, the IRA had begun to resume actions and the Provisional Government was still advocating the Belfast Boycott which was having an adverse effect on Northern mainly Unionist businesses.

The Collins/Craig pact was signed on 23rd January 1922 in an attempt to deal with these issues. It agreed to the ending of the Boycott and the reinstatement of Catholic workers to the shipyards.[3] However the pact was not sufficient to secure peace and in the month that followed violence continued to escalate, mostly in Belfast. One incident in particular soured relationships between North and South considerably.

The Clones Affray

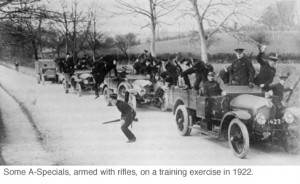

On 11th February 1922 a group of Ulster Special Constables (Northern Ireland’s armed auxiliary police force) were making the journey from Belfast to Enniskillen as part of a group which was to reinforce the border patrols in the area.

Bridges had been blown up and minor roads trenched or mined after the IRA had conducted a cross border raid kidnapping forty Loyalists.

This was itself in retaliation for the Northern authorities’ arrest of five IRA men in Derry, ostensibly travelling as part of a GAA team taking part in the Ulster final, but in reality involved in a reconnaissance mission on Derry Gaol where three other IRA men faced the death penalty.

Twelve Ulster Special Constables were shot and four killed in a fire fight at Clones train station.

The route chosen by the A-Special’s was in hindsight, clumsy at best. They arrived at Clones, in southern territory, and had to wait on another train to get them to their destination. Six of the Specials disembarked and remained on the platform whilst the others headed for the buffet.

In the meantime the local IRA had been alerted and Matt Fitzpatrick, their commandant, made his way with others to the train station. There, they called on the Specials to surrender but the latter opened fire in response and Fitzpatrick was shot dead. The other IRA men opened fire with Thompson sub machine guns on the Specials crowded on the platform and in the carriages.

In the brief fire fight which ensued, twelve Specials were shot, four killed and eight others injured along with several civilians.

The incident almost set off a huge confrontation between North and South, which was eventually calmed only when the British Government sent three British Army battalions to the border to assuage the concerns of Northern Ireland premier Sir James Craig and the IRA prisoners were set free, followed by the 26 captured Loyalists.[4]

The North Deteriorates

Meanwhile in the North violence had continued at a steady pace. The Belfast IRA were particularly active at this time and the border areas were still extremely volatile.

The most infamous murders of the conflict in Northern Ireland were committed on 24th March 1922 when the Catholic McMahon family and the barman employed by them were brutally murdered by an RIC/Specials gang led by District Inspector Nixon operating out of the notorious Brown Square Barracks on the Shankill Road.

Eight men, including all the male members of the McMahon family, who were not affiliated with Republican politics, were shot altogether and six were to die. Upwards of 10,000 people attended their funerals. Michael Collins led calls for an independent investigation into the incident but this was rejected by Craig.[5]

Over 200 people were killed in violence in Belfast in the first half of 1922

Despite this Collins and Craig would meet again on 31st March in order to try and calm the situation.[6] An agreement was reached but within 24 hours a mixed gang of RIC and Specials led by Nixon again had, in response to the IRA shooting of policeman, rampaged through Arnon Street, breaking into Catholic owned houses and killing any men they found there.

A newly widowed elderly man who had just buried his wife was shot dead as were others, but the most callous and brutal treatment was meted out to Joseph Walsh, a Great War veteran, who was bludgeoned to death with a sledgehammer whilst lying in bed with his 7 year old son. The latter was also shot and later died of his wounds. Walsh’s two year old daughter survived as did his 15 year old son who had been shot in the thigh.[7]

The Provisional Government under Pressure

Two weeks later Rory O’Connor led 200 anti-Treaty IRA fighters in taking over the Four Courts in central Dublin, in defiance of the Provisional Government. That followed an IRA convention in March were the majority of the IRA delegates had repudiated the right of the Dáil to dissolve the Republic. Things were rapidly moving out of control for Collins and the Provisional Government.

With this in mind, Collins, whose Provisional Government was under pressure from anti-Treaty elements, decided that an attack on Northern Ireland and the possibility of ending partition could be the move that would unite the two IRA factions.

The Northern Offensive was conceived as a means to heal the Treaty split in the IRA

In January 1922 minutes of cabinet meetings show the Provisional Government was happy to assist nationalist controlled county councils inside Northern Ireland who refused to recognise the new state and teachers who also took such action. In fact for a time the Provisional Government paid their wages as far as was possible.

More significant was that Eoin O’Duffy, with Michael Collins blessing, had set up the secretive Ulster Council (under the IRB auspices) whose remit was to co-ordinate IRA activity in Northern Ireland. Its chairman was to be future Tánaiste Frank Aiken.

The council included the anti-Treaty commanders of the 2nd Northern and 3rd Northern divisions, Charlie Daly and Joe McKelvey respectively. The 4th Northern division was represented by it commander Frank Aiken, who was neutral on the Treaty and the council also included 1st and 5th Northern division commanders, pro-Treatyites Joe Sweeney and Dan Hogan.

In April 1922, talks began to take place between high ranking members on both sides of the Treaty split. It was agreed that an attack on Northern Ireland would be an acceptable action but the Provisional Government and Collins had a problem. The Northern IRA was not sufficiently well armed to conduct the actions laid out in the plan.

Any weapons sent North could not be allowed to be traced back to the Provisional Government. A compromise was reached where the anti-treaty IRA would send weapons North and have those weapons replaced by Provisional Government arms supplied by the British. According to John McCoy of South Armagh in his BMH statement,

“all the Old IRA arms which had been used during the Tan campaign were collected in the south and handed to volunteers in the North. An issue of arms handed out by the British under the treaty terms would replace them”.[8]

There was also a steady stream of southern fighters making their way North in what seemed to be a fairly large scale operation. According to Michael O’Donoghue, Engineer Cork 1 Brigade IRA:

“fully equipped flying columns were also being sent up from Tipperary and from other Southern Divisions to reinforce the Ulster volunteers and sustain the attacks planned on a large scale”. [9]

Sean Lehane was appointed O/C of a new force comprising the 1st and 2nd Northern Dvisions. Lehane from Cork was to be assisted by a Kerryman, Charlie Daly.[10] Daly had been the commander of the 2nd Northern Division from early 1921 and knew the area well.

He had aired his anti-Treaty views in January 1922 and found himself replaced by Tom Morris as Commander in February. He made an impassioned defence of the accusations against him, namely that he had mismanaged the division and he was eventually brought back into the fold as Lehane’s second in command. Most of the southern men sent north were based along the border in Donegal with this unit.

O’Donoghue related a story about the build up to the offensive and the small scale actions the IRA in the Donegal/Derry area perpetrated in April including:

“One notable “stunt” which we successfully carried out was the capture of a whole train load of petrol going to the 165th Infantry Brigade of the British Army in Derry, coming from British Army G.H.Q. in Dublin. Sixteen thousand gallons of petrol was the amount of the seizure.” [11]

The date set for the planned offensive was May 1922. The leader and man behind the offensive’s plans seem to have been Eoin O’Duffy, Chief of Staff of the Pro-treaty forces. In a Department of Defence Memo in 1927 it was indicated that all operations reports were given to him directly at Beggar’s Bush Barracks in Dublin.[12]

It also suggested he would co-ordinate attacks once the offensive was launched. The offensive was to be a massive undertaking. It would, notionally, culminate in an advance on Belfast itself. All Northern units were instructed to take part and to hold out for as long as possible in anticipation of almost simultaneous Southern support from across the border. However things did not go to plan.

The Offensive begins

It was decided that the start of May would see a general upsurge in IRA activity before the offensive would become a six-county-wide uprising.

However the 3rd Northern Division in Belfast was not sufficiently well armed and encountered difficulty when an oil tanker transferring weapons and other supplies North broke down in transit. It left them in a serious situation and they felt obliged to contact O’Duffy. McCorley related:

“ We were now faced with the difficulty of having the whole operation postponed since Belfast would be abort of Its supplies. We eventually got in touch with General Duffy in Beggars Bush Barracks and conveyed our difficulty to him and asked him to agree to our getting in touch with the other Northern Divisions and having the operation called off for a period of three days.

We did get in touch with the other Divisions but the 2nd Northern Division said that it would be impossible for them to cancel the operation since final orders had been issued. The officer with whom contact was made in the 2nd Northern Division was the Vice-Commandant of that Unit, Daniel McKenna. In all the other areas the operation was called off and we understood that they would go into action on the 22nd May.” [13]

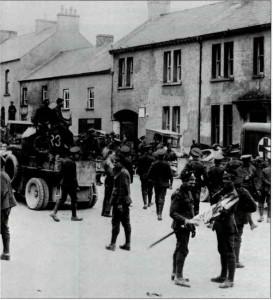

The 2nd Northern Division, in counties Derry Tyrone and Fermanagh, duly opened the offensive on 2nd May with attacks in Bellaghy, Draperstown and Coalisland. Four Ulster Special Constables (USC) men were shot with one killed in Bellaghy and the USC barracks in Cookstown and Ballyronan in County Derry were attacked with four constables being killed.[14]

The offensive began with attacks across west Ulster in Derry, Tyrone and Fermanagh.

Other actions included blowing up bridges and cutting of telegraph wires throughout the county. In Derry City the IRA attacked checkpoints at Buncrana Road manned by the USC and British Army.[15]

On 8th May eight or nine IRA men called to the house of Samuel Milligan a teenage member of the B-Specials in Castlecaufield, Tyrone and shot him. Milligan would die of the wounds received in this attack. B-Special and Loyalist retribution for the orgy of violence of the first week in May was swift and brutal.

On Thursday the 11th of May 1922 a group of armed men attacked the home of the McKeown family who lived in Ballymulderg near Magherafelt County Derry. At 2.30am a group of armed and masked men surrounded the small cottage, three men entered and the males were demanded to enter the kitchen.

Mrs. McKeown lived in the cottage with her three sons. James McKeown was the first to enter the kitchen and was met by a hail of bullets. Volleys were fired at the other 2 sons Thomas and Francis, both were severely wounded Francis received sixteen bullet wounds. All were innocent and not involved in any activity although a brother Harry was a prominent IRA member in the area.

Republican Infighting in Donegal

The 2nd Northern Division, in west Ulster, was, however isolated and stripped of the expected aid from across the border, as pro and anti-Treaty elements of the 1st Northern Division, in County Donegal, became embroiled in lethal violence with each other.

This hostility between the Divisions occurred mainly because the anti-Treaty volunteers, led by Munster men Sean Lehane and Charlie Daly, were largely from outside Donegal whilst the pro-Treaty forces, led by Joe Sweeney were comprised mainly of local Donegal units.

Instead of assisting the Northern Offensive pro and anti Treaty forces in Donegal came to blows with each other.

This friction eventually came to a head, when during a bank robbery by anti-Treaty forces in Buncrana Co. Donegal on 4th May they became embroiled in a shoot- out with Provisional Government troops who arrived to investigate. A girl aged 9 and a teenage girl of 18 were shot, later dying of their wounds. Both were innocent bystanders.

Later that day anti-Treaty forces attacked a pro-Treaty force in NewtonCunningham, a small village in Donegal about 8 miles from Derry. The pro-Treaty force was part of a 50 strong convoy driving to Buncrana after receiving reports of fighting in the area. Who started the shooting is disputed, however, as the Provisional Government troops passed through NewtonCunningham, Charlie Daly and Sean Lehane’s men opened fire on them, killing four pro-Treaty soldiers and wounding two others.[16]

Rather than marking a concerted effort against Northern Ireland, the May events in Donegal in many ways were the first shots of the Irish Civil War there. Charlie Daly would later be executed at Drumboe, in March 1923, with three others by Free State forces towards the end of the Civil War.

Operations in Belfast

Meanwhile in eastern Ulster, the 3rd Northern Division eventually sprang into action on 17th May with an attack on RIC Musgrave barracks. Constable John Collins was shot dead after the raiders had gained entry but fled empty handed when the Garrison began to rouse.

According to Roger McCorley:

“If this operation had been successful we would have gained possession of a number of armoured cars and about 250 rifles, together with a large amount of weaponry.”

The IRA had actually come extremely close to pulling off what would have been a major coup and propaganda success as McCorley continued:

“The plan of attack on Musgrave Barracks was worked out in great detail and only for one unfortunate incident would have been a great success since our people had effected an entry into the Barracks and had actually captured the main room. The cause of the failure was due to the fact that a member of the main guard on the Barracks was able to fire a shot which gave the alarm. On the Buildings surrounding the Barracks proper a number of machine gun posts had been placed and when the shot was fired these posts opened fire. Patrols outside the Barracks also opened fire through the gates of the Barracks and since we had only twenty-two men engaged in the whole operation we had to retire”. [17]

The IRA in Belfast raided Musgrave police barracks and embarked on an arson campaign against the city’s commercial premises.

The following night the Belfast IRA began attacks on commercial property that would continue for almost a month. Over eight-six premises were attacked and these arson attacks on mostly Unionist property would eventually lead to “three million pounds worth of damage”.[18]

Communal violence continued amongst the IRA offensive unabated with daily killings. One killing however would stand out. Unionist Member of Parliament William Twaddell was shot dead by the IRA on 20th May as he was walking to his business premises in North Street. His death signalled a crackdown on the IRA in Northern Ireland.

The Special Powers Act had been passed in April and now the Northern Ireland Government took full advantage of it. Internment was swiftly introduced many hundreds of suspects arrested and interned.

Frank Aiken and the Fourth Northern Division

While the 2nd and 3rd Northern Divisions had both seen action in May it was expected that the 4th Northern, based in Dundalk and composed of units from counties Armagh, Down and Louth, would soon join the action.

They had been particularly active in the border area and from April had occupied Dundalk barracks following the evacuation of its British garrison.

However the 19th May came and the 4th Northern did not enter into action. Debate has raged ever since as to why this occurred. Three other counties supposed to take part in the Rising also seem to have taken cold feet or received cancellation orders.

Aiken’s Fourth Northern Division, the best armed and most experience of the border units took no part in the offensive.

Patrick J Casey, admittedly a less than impartial witness, but who was IRA Commandant in Down, received a message stating that Frank Aiken wished to see him in Dundalk. Unhappy at this due to the large amount of planning still necessary for the offensive in the 4th Northern area he reluctantly made his way south. There he met Aiken in Dundalk barracks where he states the following occurred:

“I returned to Dundalk that evening as directed and I saw Frank Aiken. I asked him what was the position and he replied that our Division was taking no part in the rising, but that there was no cancellation so far as the remainder of the NORTHERN counties was concerned. He gave as his reason the fact that the Armagh Brigade was not fully equipped and for that reason he felt justified in withdrawing his Division from action.

I pointed out that the South Down Brigade was fully armed and that we should be permitted to take our part. He was, however, adamant and his orders were paramount. I told him also that our failure (Armagh and South Down) would mean, if nothing else, increased concentration of enemy forces in the other northern counties, but this aspect of things did not appear to interest him.

On the following morning the rising in the rest of the six County area did take place and was quickly suppressed with considerable loss of life and arms on our part. I could never understand Aiken’s real motive in not fighting his Division on this important occasion.”[19]

John McCoy could not shed much light on what had occurred in his BMH statement but he did offer this:

“I am not in a position to define exactly how this muddle of the orders cancelling the rising occurred. I believe that in the case of the 3rd Northern Division the fault lay with the pro-Treaty headquarters in not providing alternative means of notification which would ensure the order arriving by at least one route.” [20]

However in later interviews with Ernie O’Malley McCoy gave a very different account. In it he claimed there had been a countermanding order issued:

‘Men from the south were to come up, but it was called before the civil war.’… ‘Frank Aiken asked me to go down to the Brigade Adjutant in Armagh and call it off’. [21]

It seems then that Aiken had received cancellation orders at the last moment from GHQ in Beggar’s Bush. A subsequent Free State memo seems to confirm that orders to stand down may actually have been conveyed to the divisions prepared to go into action around the border:

“It should be mentioned that in connection with these operations a decision appears to have been taken that there would be no fighting on the border or around it- which decision meant there would no offensive operations carried out by the 1st Northern or 1st Midland or 5th Northern Divisions”. [22]

The Pettigo-Belleek affair

Why Aiken and his men did not take part in the offensive remains an open question. However it meant that the 3rd Northern Division were now badly isolated as the only division conducting large scale attacks. RIC barracks were attacked but soon the situation would become desperate as Internment forced many IRA men to go south on the run.

However events in Fermanagh did draw some reinforcements away from the Belfast area. The USC provoked a confrontation with pro and anti- Treaty forces which had been amassing on the southern side of the border in Pettigo which was partially in Free State territory and bordered the Northern Ireland village of Belleek.

The massing of these forces had raised Unionist fears and the USC, commanded in the area by future Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, Sir Basil Brooke, was determined to flex its muscles. The USC engaged in a fierce fire-fight with the Irish forces in Pettigo before being pushed back with heavy losses and forced to retreat. The Pro and anti-Treaty forces would pursue them and eventually occupy Belleek on the Northern side of the border.

Pro and anti Treaty IRA units fought fierce battles with the Ulster Specials and regular British forces around Pettigo.

There, the IRA force would hold out for a week before being forced to retreat back across the border by several battalions of regular British troops supported by artillery called in by Churchill. It was the largest confrontation between Republicans and the British since 1916, but eventually the IRA retreated with 7 of their mixed force dead.[23]

Collins was unhappy at the fighting there and sent an accusatory telegram to Joe Sweeney who commanded the pro-Treaty forces in the area. Sweeney had reported back that, “it wasn’t our fault at all” and stated that they had only been responding to aggression from the Special Constabulary.[24] However the actions had been an embarrassment to the Provisional Government, which did not want open confrontations with British forces.

Aftermath

The Northern Offensive had been a calamity. Cancellation orders had spread confusion as they had in 1916 which meant that the Northern units had been isolated at critical moments. The IRA now faced some serious issues in Belfast as described by Seamus Woods O/C of the 3rd Northern Division GHQ :

“The enemy are continually raiding and arresting: the heavy sentences and flogging making the civilians very loath to keep wanted men. The officers are feeling their position very keenly”.[25]

Eventually most of the Belfast IRA men would make their way south to the Curragh to await further instructions which never came. Most eventually joined the Free State’s National Army.

The 2nd Northern Division faced similar issues as Internment in particular took its toll on the units around Derry and Tyrone. The civil war would effectively decimate the force.

The Northern offensive was calamity and ended with most Northern IRA men being interned in the North or fleeing south.

The Provisional Government at the start of June had settled upon a policy of “peaceful obstruction… and no troops from the twenty- six counties either official or attached to the executive [anti-Treaty] should be permitted to invade the six county area”.[26]

Interestingly, however and paradoxically Michael Collins was still thinking in term of military action in the North right up until the end of July 1922. What exactly Collins envisaged is hard to say as the Provisional Government had obviously settled upon a very different policy. Collins wrote on 26th July,

: ‘we now have a force that means something in future dealings with Britain and the North East … The present fight [The Civil War] is only training for our troops, it gives our soldiers confidence’. [27]

Three days later he also wrote, after the British Army had shot two civilians at a checkpoint in Armagh:

‘I am forced to the conclusion that we may yet have to fight the British in the North East.’[28]

What plans he had exactly we will never know as three weeks later he was dead, killed in an ambush in County Cork, and with him any future belligerent government policy towards the North East.

The 4th Northern Division led by Aiken defied the policy of the Provisional Government, by continuing to raid into the North. Following the murder of two innocent Catholics and a sexual assault of a woman known well to Frank Aiken, by the Special Constabulary, around 30 men from the 4th Northern left Dundalk barracks to launch an attack on the isolated townland of Altnaveigh. Six innocent Protestants were shot dead in this attack, one of them a woman. Over a dozen premises were burned down or bombed. It was one of the most notorious events of the whole period.[29]

Patrick Casey in his BMH statement stated: “I remember my feeling was one of horror when I heard the details. Nothing could justify this holocaust of unfortunate Protestants”. [30]

Conclusion

Why was the Northern Offensive such a dismal failure? Collins appeared to be attempting a Tet Offensive type situation which would lead to the collapse of the Northern state whilst securing the unity of the Republican movement. However he appears to have called off his own plan.

Did the Provisional Government simply get cold feet at the last moment?

It may be that Collins was using the offensive in an attempt to prevent the split in the IRA erupting into open warfare rather than any genuine attempt at ending partition

It is difficult to say definitively, although the plan of a conventional advance on Belfast was very ambitious and it may be that Collins and other pro-Treaty figures were simply using the offensive cynically in an attempt to prevent the split in the IRA erupting into open warfare rather than any genuine attempt at ending partition.

It may be significant that none of the IRA Northern Divisions based in the prospective Free State, the 1st, 4th and the 5th Northern Divisions, took an active part in the offensive.

However the truth may not be so Machiavellian. Diplomacy with the Northern Government had been attempted in January and March with the Collins/Craig pacts but events seemed to move ahead of the Provisional Government who struggled to keep up.

The split in the IRA had led to two rival factions and Collins was only able to gain the confidence of the Northern Divisions (particularly the 3rd Northern) with support guaranteed in fighting the Northern state. It may be the case that Collins was playing for time.

Or it may be the case that Collins had a mixture of motives and was just moving from one policy to another as circumstances dictated.

As it was partition had been strengthened and the Nationalist population would find themselves in a consolidated Northern Ireland state, whose unionist-dominated government at Stormont would become renowned for discrimination and gerrymandering against the Catholic and nationalist minority.[31]

It would be 50 years before Republicans would challenge the state again in a significant way with Provisional IRA violence and a communal conflict spiralling out of control eventually forcing the suspension of the Stormont Government in 1972.

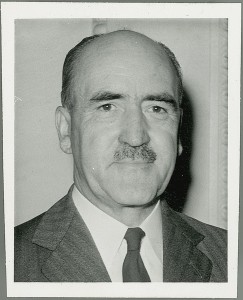

The Provisionals’ campaign would continue for another twenty-five years. Surprisingly perhaps, not all of those IRA members who had fought the infant Northern state in 1922 supported the new campaign. Speaking to Robert Kee for his History of Ireland documentary which aired in 1980, of the Provisionals’ campaign, Roger McCorley would say: “This thing, I cannot stand it. I have no sympathy with it in any shape nor form’.

It seemed for him and for Patrick Casey the failure of the Northern Offensive had led to the end of the fight for Ulster. As Casey would lament:

“and so petered out this latest, and maybe the last, rising in the Ulster area.” [32]

References

[1] For casualty estimates see here https://www.theirishstory.com/2012/07/02/the-irish-civil-war-a-brief-overview/#.XSECxehKjIU https://www.theirishstory.com/2012/09/18/the-irish-war-of-independence-a-brief-overview/#.XSEDEehKjIU

[2] Roger McCorley BMH WS Ref #: 389

[3] For the text of the Collins/Craig agreement see here https://www.difp.ie/docs/1922/Collins-Craig-agreement/226.htm

[4] The four USC killed at Clones were S/Sgt William Dougherty, S/Con James Lewis, S/Con William McFarland and S/Con Robert McMahon. http://policerollofhonour.org.uk/forces/n_ireland/usc/usc_roll.htm For more information on the Clones affray see here: https://www.historyireland.com/20th-century-contemporary-history/the-clones-affray-1922-massacre-or-invasion/

[5] For more information on the murders see here: http://www.belfasthistoryproject.com/mcmahon-family-murders/

[6] For text of 2nd Collins/Craig pact see here. http://sarasmichaelcollinssite.com/mcccagreement.htm

[7] Alan Parkinson Belfast’s Unholy War, p244-246

[8] John McCoy BMH WS Ref #: 492

[9] Michael O’Donoghue BMH WS Ref #: 1741

[10] Adrian Grant, Derry and the Irish Revolution 1912-1923, p 134

[11] Michael O’Donoghue BMH WS Ref #: 1741

[12] Matthew Lewis, Irish Historical Studies, The Fourth Northern Division and the Joint IRA Offensive, April- July 1922. War In History. Volume 21, p314

[13] Roger McCorley BMH WS Ref #: 389

[14] http://policerollofhonour.org.uk/forces/n_ireland/usc/usc_roll.htm

[15] Adrian Grant, Derry and the Irish Revolution 1912-1923. P134-136

[16] For synopsis on attack see http://irishmedals.ie/

[17] Roger McCorley BMH WS Ref #: 389

[18] Seamus Woods to O’Malley, The Men Will Talk to Me Ernie O’Malley’s Interviews with Northern Divisions, p133

[19] Patrick Casey BMH WS REF #: 1148

[20] John McCoy BMH WS Ref #: 492

[21] The Men Will Talk to Me Ernie O’Malley’s Interviews with Northern Divisions, p166

[22] Kieran Glennon, From Pogrom to Civil War, Chapter 4 Belfast after the Truce, note 81- File on Pension claims by Northern IRA personnel. UCDAD, p24/554

[23] For a full account of the weeks fighting see BMH Statement by John Travers WS#711.

[24] Kieran Glennon From Pogrom to Civil War p179-181

[25] Mulcahy Papers UCDAD P7/B/77. 20th July 1922

[26] Extract from minutes of Meeting of the Provisional Government, 3rd June 1922. No. 296 NAI Provisional Government Minutes G1/2

[27] 26th July , Collins memo on General Situation, Mulcahy Papers UCD P/7B/28

[28] Mulcahy Papers UCD P/7B/29

[29] See Matthew Lewis, Frank Aiken’s War, p150-152

[30] Patrick Casey BMH WS REF #: 1148

[31] For information on discrimination in Northern Ireland see here: https://cain.ulster.ac.uk/issues/discrimination/main.htm

[32] Patrick Casey BMH WS REF #: 1148