‘A Hopeless and Thankless job’ The Dispensary Doctor in Ireland

By John Dorney

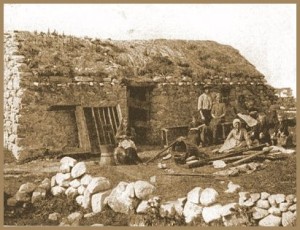

Sickness in rural Ireland before modern times was a serious business. Medical help was hard to find.

In 19th and much of 20th century Ireland, unless one could pay for a private doctor, the options were a visit to the ‘poorhouse’ or workhouse, a place that was generally hated and feared in equal measure, or getting word to the dispensary doctor.

He, (almost always a man) could be visited at his dispensary, in modern terms a clinic for ‘walk-in’ patients, but more likely he would have to make the often arduous journey on foot or by horse and cart to his patients’ homes. Many spent a lifetime in this profession, caring for the poor in both rural and urban, though predominantly rural areas.

The dispensary doctor differed from a private doctor, or most modern general practitioners today, in that he only attended to the poor who could not afford to pay for a private doctor.

He was an employee of local government, but as this changed over time, so did the structure of local health care. As such, the story of dispensary doctors is also a mirror into the changes in Irish society.

Establishment

The dispensary doctors were first established by legislation in 1805 under an Act of Parliament, by which they were defined as “an institution where medicine and advice are given gratis to the poor”.

It was supported by voluntary donations, the sum of which the 1805 Act obliged county grand juries (the equivalent of a modern county council) to match from local taxation to finance dispensaries.

However, as Laurence Geary writes: ‘the Act did not specify the location of dispensaries so, irrespective of need, philanthropy determined their establishment’. In other words the setting of dispensaries in the early 1800s was wholly dependent both on the private wealth of the district and the generosity of the local elite.[1]

The result was that dispensaries were very unevenly spread throughout the country in the pre-famine period.

The dispensary doctor provided the only affordable health care to much of the Irish poor from the 1810s until the 1970s.

The Poor Inquiry of 1835 noted that County Meath had 19 dispensaries, one for every 9,306 people. However, County Mayo, with a population in excess of 366,000, had only one public dispensary. Dr Martin A Evans, the dispensary medical officer at Clifton, claimed he was the only doctor in the whole of Connemara.[2]

This geographical imbalance in medical care for the poor was ameliorated somewhat by the Poor Law Act of 1838, which divided Ireland into 130 administrative units known as Poor Law Unions, each to have its own workhouse, governed by the Poor Law Guardians, who were elected by the rate payers within the Union’s area. The dispensaries were henceforth to be run by the Poor Law Guardians. [3]

Appointments

The dispensary doctor was appointed by local government. In the early 19th century this meant by the county grand jury and after 1838 it was the Poor Law Union guardians who made appointments.

One study of an appointment of a dispensary doctor in Charlestown, County Mayo in 1880 gives us an idea of what the process was generally like. The existing doctor was asked to resign ‘as he is now a very old gentleman and a long time in the service’. The committee subsequently met and agreed that the new applicant could be granted a salary of £120 a year, along with expenses.

Dispensary doctors were appointed by local government and as such were often subject to the whims and biases of those bodies.

The committee considered four applicants and eventually elected one doctor Stritch. They also resolved to build a dispensary in the district at cost of £900.[4]

While this is a very specific case, it probably shows the procedure in all Poor Law Unions across the country.

The system of election came in for some criticism, being subject as it was, to the whims of local politics. One election of dispensary doctor in County Kilkenny in 1828, for example came down to an ugly sectarian confrontation between Catholic and Protestant rate payers.

Dr Robert Collis in The State of Medicine in Ireland (1943) described the dispensary service as it was in the 19th century:

“Each dispensary was governed by a board of guardians. A Carmichael Essayist of the time described these committees as among ‘the lowest forms of life’. The guardians in those days elected the doctor; every form of graft, religious fanaticism and nepotism was the rule of these elections.”[5]

This may be an exaggeration but it gives us an idea of the local politics that probably always influenced appointments to dispensary doctors and other employees of the Poor Law Unions.

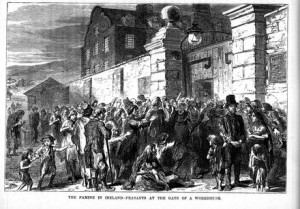

The Great Famine and after

During the Great Famine of 1845-49 the dispensaries were, predictably, overrun with the sick and starving and were supplemented by temporary Fever Hospital dispensaries set up under an 1846 Act, which operated until 1850.

From July 1847 onwards, the central board of the fever dispensaries recorded 332,462 patients being treated in the temporary hospitals, of whom 34,622, or just over 1 in 10, died. [6]

In wake of the great calamity of the 1840s, the position of the dispensaries was clarified in the 1851 Medical Charities Act, which introduced a state-funded dispensary system to provide free medical aid to the poor sick. Unlike the pre-famine dispensaries, these were to be funded from local taxation, not voluntary contributions and was subsidised by the central government body the Poor Law Commission. The latter was replaced by the Local Government Board in 1872.

After the famine the dispensary doctors’ position was somewhat improved and they were put under the control of the Poor Law Unions.

The 1851 Act established 723 dispensary districts throughout Ireland, to be governed by the boards of Guardians of the Poor Law Unions. The dispensaries were to be managed by a committee elected from the Guardians and from local rate payers.

The Act also ordered the Poor Law Unions to codify who was entitled to avail of the care of the dispensary doctors. To attend the dispensary, one needed to have a colour-coded ticket, dispensed by the committee. A black ticket entitled the holder to be treated at the dispensary itself, while red allowed the patient to be visited by the doctor in his or her home.

While such tickets were supposed to be free, being under the control of what was effectively a local political body dominated by landlords and businessmen, there were, perhaps unsurprisingly, widespread allegations of corruption and favouritism in the dispensing of tickets. [7]

The Poor Law committee could also be quite miserly in their distributing of tickets, for example one man’s ticket was cancelled in Co Mayo in the 1880s when the committee learned that he owned several head of cattle and was therefore not poor enough to qualify for free medical care.[8]

In 1863, the dispensary doctors were made registrars of births and deaths and of Roman Catholic marriages and the practice of registering births, marriages and deaths was standardised on the 1st of January 1864.[9]

After Irish independence in 1922, the workhouse or Poor Law Union, system was abolished. Indeed the abolition of the workhouse system, ‘the odious, degrading and foreign Poor Law System’, was specifically cited in the Democratic Programme of the first Dail in 1919, which, called for the ‘substituting [of] a sympathetic native scheme for the care of the Nation’s aged and infirm’.[10] The workhouses were largely closed down and some of their facilities turned into County Homes or hospitals.

However the dispensaries do not seem to have attracted the same ‘odium’ and they continued under the Irish Free State until the 1970s. When the system of Poor Law Guardians was abolished, the responsibility for the dispensaries was handed over to the local Boards of Health. The dispensary system lasted until 1972 when the present General Medical Services (medical card) scheme was introduced. [11]

A person of standing in the local community?

Pediatrician immunizing a little girl while other children are watching

The role of the dispensary doctor was to provide care to the poor who could not otherwise afford it. He provided treatment at the dispensary itself and at patients’ homes. They were also responsible for such things as vaccination for smallpox and other diseases and for dental care in many cases.

However, in contrast to private practitioners, the dispensary doctors appear to have been looked on as being lower down the social scale than other doctors. Robert Collis wrote in 1943 that;

‘The dispensary doctor had to trudge long miles on foot, and ride through bogs and up watercourses to reach his patients. His pay was hopelessly inadequate and he had no regular pension so that he hung on long after he was fit for work. Many died of overwork and quite a few of drink. It was a hopeless and thankless job, and the bad name ‘dispensary doctor’, ‘Oh, he’s just a dispensary doctor’, came from those days’. [12]

A case study of the dispensary in Tallaght, County Dublin in the 1830s and 40s bears this out to some degree. The dispensary doctors there, Dr Burkitt, had to tend to a population in the area of about 6,500 and Dr Burkitt had to visit and treat the sick poor in their homes and attended one dispensary every day. He had to travel on foot or by horse, which he had to pay for himself.

He attended all cases personally where medical or surgical aid was required, and he reported to the Poor Inquiry in 1834 that his annual ‘case load’ varied from 1,000 to 1,200 cases per year from 1831 to 1833. His salary was 20 guineas or £105 per annum. However, the local committee only paid him his full salary for those years after repeated complaints at the end of 1833. [13]

All that said, as the position of the dispensary doctor was regularised after 1851, it seems likely that the prestige of the position also improved significantly. For instance, the salary of the dispensary doctor in Charlestown in the 1880s (cited above) at £120 per year, was nearly three times the average wage of an unskilled labourer in 1904 (20 shillings per week). [14]

So certainly the dispensary doctor would have been part of the rural middle class and would have had some social standing; even if the upper reaches of the medical profession may have looked down on him.

By the era of Irish independence struggle (1912-1923), a dispensary doctor seems to have been a thoroughly ‘respectable’ profession. One Joseph Roantree of Newbridge County Kildare for instance, was described by his nephew Kevin O’Sheil as ‘persona grata with the local British garrison’ and ‘had the entre into the officers messes and lounges’ at the Curragh camp.[15]

Patrick McCartan, a staunch republican, was dispensary doctor for the mountainous region of Gortin, County Tyrone and despite his politics, was on very good terms with the local unionist landowners, the Cole Hamilton family of Beltrim Castle, who regularly put him up.[16]

One dispensary doctor and also Sinn Fein election candidate Vincent White found himself battling the deadly 1918 flu epidemic in Waterford, where many of those afflicted in the city’s poorer quarters were opposed to his political allegiance. He recalled,

‘I was the sole dispensary doctor in Waterford City at the time, and night and day I had to be on my feet answering what seemed an endless line of calls…Hushed now were the political jibes which had been flung at me as I went into houses in lanes and alley-ways seeking to bring succour to the many victims of that terrible malady which was raging throughout Europe and was leaving behind it a grim tale of many deaths.

The subsequent violent conflict in Ireland, put some dispensary doctors in a difficult position; some IRA veterans recall dispensary doctors treating their wounded, while others record a dispensary doctor in Cork being court martialled and exiled from Ireland by the IRA after refusing to treat their wounded men following the Upton ambush in February 1921.[17]

On the eve of their abolition in the 1960s, the position of the dispensary doctor does not seem to have markedly improved. There were by that time 674 dispensary doctors in the country, assisted by 151 nurses. According to Mary Daly, ‘dispensary doctors were chronically overworked; some allegedly cared for up to 2,000 patients’. Their duties included everything from routine health inspections to home births. However by that time, they tended to ‘send for the ambulance’ to treat serious cases.[18]

Nevertheless, the dispensary doctor provided health care for the Irish poor for well over a century of Irish life and therefore at least in hindsight, deserves some appreciation.

References

[1] Medical History in North Cork Mallow Field Club Journal No. 19 Article by Prof. Laurence Geary, History Department, University College Cork.

[2] Muiris Houston, Dispensary Doctors, Life Before the GP, Irish Times, September 21, 2004 https://www.irishtimes.com/news/health/life-before-the-gp-1.1158599

[3] Laurence Geary, The Irish Healthcare System | An Historical and Comparative Review. Online here.

[4] Cathal Henry, Charlestown Dispensary History 3, Online here.

[5] Houston

[6] Geary, Medical History of North Cork

[7] Geary, The Irish Healthcare system.

[8] Cathal Henry, Charlestown Dispensary History 3, Online here.

[9] Brian Donnelly, The History of Medicine in Ireland. http://historyofmedicineinireland.blogspot.com/2015/03/the-historical-development-of-irish.html

[10] https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Democratic_Programme_of_the_First_D%C3%A1il

[11] Houston, Dispensary doctors.

[12] Houston

[13] Sean Bagnall, Pre Famine Public Health, History Ireland Jan/Feb 2009 https://www.historyireland.com/18th-19th-century-history/pre-famine-public-health/

[14] Information on average salaries here http://www.askaboutireland.ie/reading-room/history-heritage/pages-in-history/Ireland%20in%201904/the-world-of-work/

[15] BMH WS 1770 Kevin O’Shiel

[16] BMH WS 1770 Kevin O’Shiel

[17] For Vincent White’s recollections see BMH WS 1764. For a sympathetic dispensary doctor who treated IRA men see Timothy Crimmins BMH WS 1051, for the unfortunate doctor who was exiled see Dennis Louran, WS 470, p.21

[18] Mary Daly Sixties Ireland, Reshaping the Economy State and Society, p243.