Commemorating 1920 in 2020 – the Perils of Reconciliation

By John Dorney

The coming year 2020, is a hundred years since the real start of the Irish War of independence. In 1919 Sinn Fein declared the First Dail and Irish Independence, but the year’s body count was low.

Nineteen-twenty was different, as the republicans launched a guerrilla insurgency against the British state in Ireland and that state hit back with bloody counter-insurgency.

Commemorating the Irish War of Independence is much more delicate than remembering the Rising of 1916 and cannot be stripped of political significance.

Commemorating 1920 will prove delicate for the Irish state for many reasons. One being the potentially antagonistic result of evoking the political violence of the era.

But another is that the suggestion that the commemoration of such a bloody and polarising time can be about ‘reconciliation’, like the 2016 commemoration of the Easter Rising, is probably wishful thinking.

A bloody year

One of the problems will be that unlike 1916, the type of violence of the War of Independence is very difficult to frame in the Irish government’s preferred lens of ‘reconciliation’. Violence was ugly, up close and personal, only very rarely ‘gallant’ face to face combat.

That we perceive such a sharp difference may say something more about our cultural perceptions of the use of violence than about reality.

For instance, far more uninvolved civilians – about 280 – were killed in the supposedly honourable five days of fighting in Dublin at Easter 1916 than in any single act of political violence in 1920.

But open combat, where both sides wore uniforms, identifying themselves as combatants and taking a ‘soldier’s risk’ was seen at the time (and even today) as ‘upright’ and ‘manly’, as opposed to ‘cowardly’ assassination, where victims were killed when unarmed and defenceless.

The violence of 1920 was very rarely ‘gallant’ combat, but up close and personal, assassination, ‘outrage’ and reprisal.

Whereas for instance insurgent leader James Connolly could say in 1916, before his execution, that the British soldiers had ‘done their duty according to their lights’ and the British Prime Minister Asquith acknowledged that the rebels “conducted themselves with great humanity…[and] fought very bravely and without outrage”, neither side was saying this in 1920.

Rather, the conflict of 1920, unlike the open warfare of 1916, was a war of ambush, assassination and reprisal. Of course, this guerrilla warfare, coupled with mass political mobilisation were also far more effective political tactics than was the failed insurrection of 1916.

Still, many IRA operations were very ugly indeed, notably Michael Collins’ Squad’s purge of Dublin Metropolitan Police G Division detectives and British Army intelligence officers. And Crown forces, including the RIC police, their reinforcements from Britain in the Black and Tans and Auxiliaries, and the British Army, retaliated indiscriminately on many occasions.

A few standout examples will illustrate the point.

In March 1920 the IRA in Cork city shot dead an Irish RIC constable and in reprisal, local RIC men assassinated the mayor of Cork, Tomas MacCurtain, breaking into his home in front of his wife and children and shooting him dead.

In the summer of 1920 the IRA retaliated by shooting RIC District Inspector Swanzy, held to be responsible for MacCurtain’s death, as he was leaving Church in the Antrim town of Lisburn.

Loyalist mobs retaliated by setting fire to the Catholic district of the town. In Belfast and Derry, dozens were killed in subsequent rioting and thousands Catholic workers were driven from their jobs in the Belfast shipyards. The summer of 1920 also saw the passing of the Government of Ireland Act, which would create Northern Ireland.

There is no way to frame the events of 1920 in terms of apolitical ‘reconciliation’.

There is simply no way to frame such events in terms of ‘reconciliation’, either in the North or between North and South. And things were only darkening in 1920. The death toll spiked sharply in November of that year.

In November, in retaliation for the hanging of Kevin Barry, a young IRA member who had been involved in the shooting of two equally young British soldiers, and the death on hunger strike of Cork mayor Terence MacSwiney, IRA general orders were issued to shoot all Crown forces on sight.

While not all IRA units obeyed the order, in county Kerry the IRA shot 16 RIC men, killing seven, in one day. Two RIC constables – one long service constable and one a Black and Tan – were ‘disappeared’ in Tralee, reputedly thrown into a furnace in the town, but apparently in truth secretly buried.

In retaliation the local RIC and Black and Tans ransacked Tralee, shooting dead two suspects and cutting off all food to the town for a week, attempting to force the release of the two policemen, who were in fact already dead; an episode known as the ‘siege of Tralee’

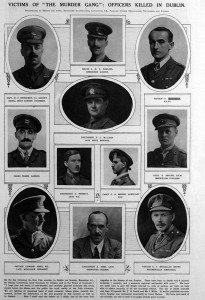

A week later was Bloody Sunday in Dublin where Collins ordered the mass killing of British agents in Dublin. Fourteen British personnel were killed that morning, mostly shot in their beds, in some cases in front of their wives or lovers. This was followed, notoriously, by a mixed force of British military, RIC and Auxiliaries shooting up a Gaelic football crowd at Croke Park, killing another 14 people.

And this bloodbath was quickly followed by the Kilmichael ambush, seven days later, in which Tom Barry’s IRA column wiped out a patrol of 18 Auxiliaries. Some of whom were killed after they had surrendered. Whether they surrendered sincerely or otherwise is debated, but Auxiliaries were certainly killed after putting up their hands and finished off while lying wounded on the road in west Cork.

And the year was rounded off with an Auxiliary company in Cork city burning out the heart of the city in reprisal for an IRA ambush.

These are only some of the standout violent incidents of 1920 in Ireland. Hundreds of Crown forces, mostly police, as well as IRA Volunteers and civilians, lost their lives. The IRA also killed civilians as informers, though few compared to the following year. Many localities had their own stories: Trim, Balbrigan, Granard and Tuam, among many others, also suffered heavily due to police, Black and Tan, or Auxiliary reprisals.

Commemorations without meaning?

It is all very well for historians to remember and tell the stories of these events, but they pose very difficult challenges for public commemorations; especially ones that have an aim of ‘reconciliation’.

Commemorations ascribe meaning to an event. They are not value free.

Commemorations are above all about ascribing meaning to an event. And it is difficult to see how commemorating such a vicious guerrilla war can be done without apportioning blame, or without considering the political import of violent actions.

Was, for instance the burning of Cork by the Auxiliary K Company in December 1920 wrong? If so, was the ambush that provoked it also wrong? Are the IRA men of Cork No. 1 Brigade who threw the grenades into the convoy at Dillon’s Cross equally as culpable as the Auxiliaries who burned down the city hall and Carnegie library in reprisal and fired on the firemen who tried to put out the blaze?

If not, are Irish politicians prepared to say publicly that an act of political violence was legitimate and that British rule and its forces’ actions were illegitimate? The same question applies to Bloody Sunday in Dublin. There are no easy answers, nor any way to say that all participants in the conflict were equally honourable nor that their causes were equally justified.

It was clear even before they started that 2020, if the government dared to venture into its centenary commemorations too deeply, would be significantly more difficult than 2016 was.

The RIC Commemoration

The government’s official commemorations got off to a fairly disastrous start when plans to commemorate the RIC and Dublin Metropolitan Police in Dublin Castle on January 17 had to be deferred after a storm of public protest.

It was one thing to say that there was a political conflict and, as Sean O’Faolain said about his own father, an old RIC constable, ‘Men like my father were not traitors. They had their loyalties and they stuck to them’, it was quite another thing, to say, as Minister Charles Flanagan did, that they were ‘murdered’ while ‘upholding the law and protecting the community‘ in 1919-1921.

Aside from the question of ‘whose law?’ which is posed by creation of separatist parliament in Dublin in 1919, the law the RIC was upholding from 1919 to 1921 was largely emergency law, the Defence of the Realm Act and the Restoration of Order in Ireland Act of 1920.

The public row over the proposed RIC commemorations exposed clear fault lines in historical memory that cannot be papered over.

These allowed for banning ‘dangerous’ organisations such as the First Dail, Sinn Fein and the Volunteers and after 1920, their internment without trial and execution of civilians by military court martial. It also enabled Crown Forces to inflict ‘official reprisals’ on the population in retaliation for IRA actions.

What was more, the RIC, particularly, though not only, the recently recruited constables or ‘Black and Tans’ and the Auxiliaries, regularly operated outside the law, shooting civilians and IRA suspects and burning homes and property at will.

To suggest that commemorating the RIC dead and them alone, at the beginning of the centenary showed ‘maturity’, suggested that either the government did not understand the causes of the vicious partisanship of Ireland 100 years ago or thought that it no longer mattered. They were wrong.

Descendants of RIC men (and at least half of the police dead were indeed Irish) may indeed mourn and honour them with as much sorrow and reverence as their counterparts with family in the IRA. But suggesting that their causes were equally justified appears to be a step further than the Irish public was willing to go.

More broadly, however, what the controversy hammered home, was that value-free commemorations of 1920 and of the War of Independence, partition and Civil War in general are not possible. It is not ‘mature’ to impose a false consensus but rather to understand the political differences that led to bloody strife in Ireland 100 years ago and how they shaped the Ireland of today.