Book Review: Birth of the Border: The Impact of Partition in Ireland

By Cormac Moore

By Cormac Moore

Published by Merrion Press, 2019

Reviewer: John Dorney

This year, 2020, marks 100 years since the passing of the Government of Ireland Act through the House of Parliament at Westminster and the effective creation of Northern Ireland. Northern Ireland’s parliament received executive powers from London in November 1921 and its existence was confirmed under the Anglo Irish Treaty, signed the following month. In 1925 it was confirmed that the border would not be redrawn to reassign majority Catholic and nationalist areas to the Irish Free State.

Ever since then, the advent of a border in Ireland has been the cause of much contention, a great deal of angry rhetoric and at times, not a little bloodshed. Was the partition of Ireland, as nationalists and republicans maintain, the mutilation of Ireland’s ‘natural unity’, the imposition of an ‘artificial boundary’ and the stranding of the northern nationalist minority on the wrong side of it in an artfully crafted unionist ‘statelet’?

The legitimacy of the border in Ireland has always been bitterly contested.

Or was it rather, as Ulster unionists would prefer to see it, an act of self determination on behalf of the Ulster Protestant people, equally as valid as the separation of the rest of Ireland from the United Kingdom? Even today there is little convergence of these mutually exclusive, indeed hostile viewpoints.

In this study of partition, Cormac Moore tries not to take sides in these partisan communal debates, but rather attempts to give a comprehensive picture of how partition came about and how it affected life in Ireland. His account ranges from high politics; of Acts, Treaties and Boundary Commissions, to the violence that accompanied the ‘birth of the border’, to the nuts and bolts of how civil service, law education and infrastructure were separated.

There are also chapters, notably those on religion and sport, which maintain that partition’s impact on social life across the island were perhaps not as great as might be imagined. All of Ireland’s main religions and almost all of its sporting organisations (soccer is the main outlier here) remained all Ireland bodies.

High Politics

On the high politics of partition, Moore’s narrative is in some parts familiar; following Ronan Fanning in his The Fatal Path in arguing that unionist resistance to Home Rule in 1912-14, backed by elements of the Conservative Party, all but guaranteed that there would be some sort of partition on the island.

What is new and interesting, however, is Moore’s exploration of how Ulster unionists went from rejection of Home Rule in principle to their acceptance of their own Home Rule parliament in Belfast.

Moore argues that, since Home Rule for Ireland had passed into law in 1914, the Conservative dominated British government and in particular Walter Long, First Lord of the Admiralty, had to find a solution in 1918-19 that implemented some form of Home Rule while at the same time honouring the guarantees they had given to Ulster Unionists in 1914 that they would not come under a Dublin government.

Moore argues that as late as the Treaty of 1921, the final form of partition was still up for grabs.

The result was the Government of Ireland Bill that envisaged two Home Rule parliaments, one in Dublin and one in Belfast. That the latter would administer a six county rather than a nine county Ulster was the result of Long’s closeness to the Unionists (Long himself had at one time been leader of the Irish Unionist Alliance) who wanted a safe Unionist majority in their zone. They also however wanted majority nationalist counties Fermanagh and Tyrone and towns such as Derry city and Newry, all of which they got, in spite of the opposition of many of the inhabitants of those areas.

Some historians, notably Fanning, argue that these decisions taken in 1919-20 decided the future of Ireland and that all that followed was a mere epilogue. Moore however argues that at the time of the Treaty, while the existence of some form of Belfast-ruled enclave in the North was inevitable, the inclusion in it of such a large majority nationalist area in its west was not. Lloyd George for one acknowledged in private to Winston Churchill that as regards the inclusion of Fermanagh and Tyrone in Northern Ireland, ‘our case is not a strong one’.

Moore argues that the republican negotiating team at the Treaty negotiations, led by Michael Collins and Arthur Griffith, could have done much better on this point and need not have so trustingly accepted that a Boundary Commission would deliver to them the majority nationalist fringe of Northern Ireland. It did not of course, alter the border in the end, citing Article 12’s clause that as well as the ‘wishes of the inhabitants’ the Commission had to bear in mind ‘economic and geographic’ concerns. In the event even its very limited adjustments of the border were never implemented.

This failure of negotiation on behalf of the leaders of the prospective Irish Free State was due perhaps to naiveté rather than southern self interest. But it was indeed naked self interest – the need to raise revenue during the Irish Civil War, that caused the Free State to impose a customs barrier on the border in 1923, which was one of the main factors in reinforcing partition in everyday life.

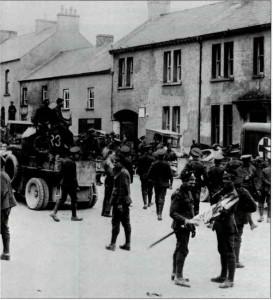

Violence

Moore chronicles the deadly violence that accompanied partition, which claimed well over 500 lives in the north from 1920 to 1922. Catholic refugees from the north into the south helped to destabilise the infant Free State in 1922 – anti-Treaty republicans seized buildings illegally to house them in defiance of the Provisional Government. Meanwhile there was also a smaller though substantial movement of Protestants from south to north as well many RIC policemen and their families.

One of the Ulster unionists, Cavan man, Somerset Saunderson, stranded on the ‘wrong’ side of the border declared ‘I have no country’, while as Moore notes on northern Catholics, they ‘were reluctant to recognise Northern Ireland or participate in its institutions [but] no attempt was made to assimilate them either.’

Of the parties to the conflict, Moore singles out the Ulster Special Constabulary for their ruthlessness, though he acknowledges that the IRA also targeted civilians, though their reprisals were ‘not as numerous’ as those of the Specials. Ultimately though, British military backing for the Northern authorities as well as the outbreak of Civil War in the south, meant that partition was never seriously threatened by force of arms.

Consolidation

Perhaps most interesting thing about Moore’s book is the account of the nuts and bolts of partition; how Ernest Clarke, Assistant Under Secretary for Ireland, arranged for the transfer of civil servants from Dublin to Belfast, in effect creating a new governing apparatus in the latter.

One of the more striking arguments to emerge here is that, of the two governing apparatus to emerge on the island, it was the Dublin government which was largely the heir of the British administration in Dublin Castle.

Most of Northern Ireland’s institutions had to be created from scratch.

In some ways, Northern Ireland’s administration was the novel entity, while the Dublin government inherited many of the institutions of British rule.

Sadly, many of these institutions, as Moore shows, had a sectarian tinge. All public employees including teachers had to take an Oath of Allegiance after 1923; the response of the Northern government to many national teachers taking their salary from and giving allegiance to, the Free State government in 1922. The Church ultimately agreed that their clerics and teachers would take the Oath, in spite of condemnation by republicans.

In a rather depressing reminder of recent debates in contemporary Northern Ireland, we find here that the Northern authorities were contemptuous of proposals to include the Irish language in education north of the border. ‘Not worth spending money on’ was the judgement of one official, Robert Lynn.

Meanwhile, we learn, the proposal of Chief Secretary for Ireland Ian McPherson in 1919 to provide free, state-run, non-denominational education was condemned by the Catholic Church as ‘anti Irish and anti Catholic’. Segregated education remains a serious barrier to inter-communal integration in Northern Ireland today.

This is a very well researched book, and even those familiar with the topic will find much that is new in it.

While the Catholic Church’s position on education was obviously partisan, Moore is not the first historian to point out that the New Northern Ireland authorities were indeed largely anti-Catholic and anti Irish nationalist. He shows how the discrimination against northern Catholics in employment, electoral boundaries and elsewhere was rife and also that the Northern government was most reluctant to cooperate with its southern counterpart even on areas of mutual benefit such as electricity supply.

Moore concludes that ‘the partition of Ireland was the most significant event in modern Irish history’. This is somewhat debatable, as the independence of the two thirds of Ireland that today form the Republic was at least equally important. Many denizens of the Free State and then Republic have at times been surprisingly unconcerned with events north of the border ever since.

To conclude however, this is a very well researched book, covering a great deal of ground not trodden by other accounts, which confine themselves to the politico-military dimensions of partition. Even those familiar with the topic will find much that is new in Birth of the Border.