Commemorating the Partition of Ireland, 100 years on.

By Cormac Moore

One hundred years ago, Ireland was in the midst of violent strife surrounding the struggle for Irish independence. In late 1920 the British Parliament passed the Government of Ireland Act, setting up two Home Rule parliaments, one in Dublin and the other in Belfast, the latter to govern the six counties that would form Northern Ireland.

The Irish government’s plans for the Decade of Centenaries from January 1920 to September 1923 were recently announced, with Cork scheduled to play a central role for events earmarked for 2020. Even though some of the key events that led to the partition of Ireland occurred in 1920 and some of the worst violence that took place that year did so in the north-east of Ireland, it appears the government has no specific plans to mark the division of Ireland until 2021.

Marking partition

Partition ‘will be marked by an academic conference that year in Queens University Belfast (QUB) looking at the impact of partition both in Ireland and in other countries that were partitioned in the post-war settlement.

There is also a commitment in principle by the Government to have a study of what happened to the Protestants on the southern side and Catholics in the north after partition and to have a cultural centre in one of the border counties. Now that the Northern Ireland Assembly is up and running again, it will be interesting to see how partition is marked in the North with the two largest parties holding totally contrasting views on partition.

With partition being the most live and contested issue from the Decade of Centenaries, perhaps it is not surprising that the Irish government has chosen to tread so lightly with it. The government’s lack of emphasis on partition is also a reflection of the general knowledge of and somewhat indifference to the events that led to the division of Ireland from those furthest from the border.

Violence in the north in 1920

The recent controversy over the proposed RIC/DMP commemoration in Dublin Castle has highlighted this. Most commentary in the media and on social media focused on the RIC’s role in the south, west and east of Ireland during the War of Independence.

There was much comment on the resignation of Jeremiah Mee from the RIC after Colonel Gerard Smyth appeared to instruct RIC members to shoot IRA suspects, yet little was mentioned of the impact Smyth’s death in Cork had on events in Belfast. His death at the hands of the IRA in July 1920 was the catalyst for the shipyard expulsions of Catholics and socialist Protestants and the subsequent sectarian violence that engulfed Belfast from the summer of 1920.

The killing of Cork’s Lord Mayor Tomás MacCurtain in March 1920 by the RIC also came in for much comment. Yet the killing of one of those accused of MacCurtain’s death, RIC District Inspector Oswald Swanzy in August 1920, was barely remarked upon.

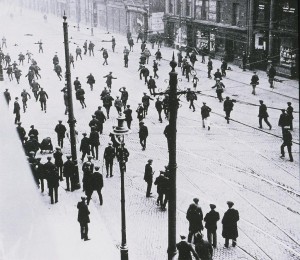

Swanzy’s death in Lisburn led to the expulsion of almost the entire Lisburn Catholic population from their homes, 300 homes were destroyed. The rioting spread to Belfast where 22 people were killed in just 5 days.

Incidents in places such as Balbriggan, Cork City, Tuam, Clare and Croke Park were stressed with little mention of the role of policing in Belfast during the waves of violence that accompanied partition. The roles of the Black and Tans and the Auxiliaries were highlighted extensively and yet the role of another controversial quasi-military police force formed in 1920, the Ulster Special Constabulary received sparse attention.

Charles Wickham, the divisional commissioner of the RIC in Ulster, was placed in charge of the Specials, whose actions were subject to local RIC authority. Emphasising the partitioning of Irish history, the mayors of Belfast and Derry were not invited by the Irish government to the now postponed commemoration for the RIC and DMP in Dublin Castle, even though the RIC was an all-Ireland body.

‘Shared history’?

There has been much talk of understanding our shared history on the island of Ireland in all its complexities and yet little attempt has been made to truly understand how Ireland was divided in the first place and the impact this has had, not just on people from Northern Ireland or the border counties, but on everyone on the island.

The Ulster question and the partitioning of Ireland is central to the Decade of Centenaries. The introduction of the gun into Irish politics during this period came about due to Ulster’s opposition to Home Rule. Most of the subsequent events over the following decade stemmed from that moment.

Partition did not just happen in 1921. There was a long and meandering road to the creation of Northern Ireland. 1920 alone was a pivotal year. The Government of Ireland Bill manoeuvred its way through the Houses of Parliament for most of the year, enacted by King George V in December 1920.

The extreme violence that accompanied partition, much of it sectarian in nature, started in the summer of 1920, leading to the violent deaths of over 550 people, mainly in Belfast, over a two year period, as well as the expulsion of many workers from their jobs and the displacement of thousands from their homes. The Specials were formed in late 1920 and a crucial figure in creating the structures of a functioning Northern Ireland jurisdiction, the civil servant Ernest Clark, was appointed that same year. These events were not divorced from events elsewhere in Ireland.

Newton Emerson, offering a unionist perspective recently on commemoration, stated ‘what is needed, certainly in the first instance, is respect for two different views of history’. I wholeheartedly agree with the sentiments of this point. That does not mean we ignore the history of partition though.

In the same article, he also stated, ‘for unionists…Ireland split into two peoples with separate histories’. This is a considerable simplification of partition which ignores the significant nationalist minority which made up one third of the Northern Ireland population in 1921. Undoubtedly a wide schism developed politically between both Irish jurisdictions, but most organisations, many unionist in nature, remained all-Ireland bodies after partition. Is that shared history to be ignored?

It is imperative that the foundation histories of the Irish Free State and Northern Ireland are not treated separately as they are inextricably linked. As we enter the most contested and complex phase of the Decade of Centenaries, it is important to halt the partitioning of Irish history and to embrace wholly the largest legacy issue from the decade, the division of this island.