The Parnell Bridge Ambush, Cork, 4 January 1921

By Caoimh Mulvany

County Cork was the epicentre of guerrilla warfare in the Irish revolution; a storm that swept over the Provence of Munster and neighbouring counties.[1]

From the beginning of 1920 to the Truce of 11 July 1921 Cork’s three IRA brigades hit the British forces stationed in the county in increasingly large and sophisticated ambushes.[2]

The Cork No. 1 Brigade, with its headquarters and leadership in Cork city earned its reputation as one of the most formidable fighting units active during the war.[3]

Cork city saw the largest British Army deployment to Ireland during the War of Independence; the 6th Division being headquartered there,[4] as were a company of the elite Auxiliary Division of the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC).[5] These formations, alongside the city’s regular police force, recently reinforced with wartime recruits known as Black and Tans, made up a city garrison numbering as many as 4,360 personnel.[6]

The IRA Cork No. 1 Brigade’s two city battalions launched numerous attacks on Crown forces throughout the War of Independence.

The IRA Cork No. 1 Brigade’s two city battalions, the 1st and 2nd, were not cowed however and launched numerous attacks on these forces.[7] These operations usually took the form of assassinations but a number of larger attacks were launched against armed bodies of Crown force personnel. Of the twenty-three Crown force fatalities suffered in Cork city during the war seven were inflicted in IRA attacks on armed RIC or British army units. [8]

Ambushes mounted in an urban environment entailed their own operational nuances and required a particular tactical approach. Volunteers usually operated with their local companies but a city-wide active service unit (ASU) was set up in early 1921.

In the successful ambushes on Barrack Street on 8 October 1920 and Dillon’s Cross on 11 December 1920, the rebels employed the hit and run tactics, armed with only revolvers and home-made grenades.[9] These urban guerrilla tactics were again employed in the third and largest attack launched by the IRA in the city, the Parnell Bridge ambush of 4 January 1921, though this one was also to use rifles and a machine gun.

The Ambush

It was a Wednesday evening, 4 January 1921; Cork city centre was bustling with activity.[10] Despite the on-going guerrilla war and the extension of Martial Law being declared that very day, city dwellers were encouraged by abnormally mild winter weather and flooded the streets.[11]

It was a Wednesday evening, 4 January 1921; Cork city centre was bustling with activity.[10] Despite the on-going guerrilla war and the extension of Martial Law being declared that very day, city dwellers were encouraged by abnormally mild winter weather and flooded the streets.[11]

Just south of the river Lee, in the City Hall/Anglesea Street area, along with the regular tram cars and vehicular traffic, a few citizens were out for their evening walks to and from the affluent suburbs of Douglas and Blackrock.[12]

The IRA ambush party attacked an RIC patrol with hand guns, grenades and machine gun fire.

Here, Parnell Bridge served as a busy junction of the tramway service out of the city, and as a swing bridge that allowed trading vessels access to the south channel of the Lee.[13] The adjacent Union Quay hosted the main police headquarters in the city, from where foot-patrols were deployed throughout the city each evening; a routine that had been identified by IRA intelligence officers in the proceeding weeks.[14]

As the evening progressed, the weather grew harsh and the setting sun left the quietening streets in partial darkness.[15] As usual, a police party of one sergeant and nine constables left the RIC station at roughly 7.30pm[16]. After a few minutes of conversation outside, they moved off in twos making their way in extended order along the quay towards Parnell Bridge.[17]

At the end of the street a contingent of roughly a dozen IRA Volunteers waited in the shadows amid the ruins of Cork City Hall and Carnegie Library – burned by the Auxiliaries in reprisal for an IRA ambush in December 1920.[18]

The IRA party consisted of hand-picked officers and experienced gunmen, all armed with revolvers and grenades.[19]

As the first two policemen neared the end of the quay and approached the bridge several grenades rained down on them.[20]

The explosions decimated the patrol’s vanguard and signalled to the rest of the Volunteers to join in the attack.[21] The police party’s commanding officer Sergeant O’Driscoll had been at the head of the patrol and was severely wounded in the initial assault.[22]

Before the smoke cleared from the opening salvo, the ambushers advanced on the patrol with rapid revolver fire; across the river a smaller IRA section opened up with rifles and automatic fire from a Lewis machine gun.[23]

In the initial confusion some of the constables attempted to retreat back to the station, while others fled towards the bridge and inadvertently towards the main body of the attacking force.[24] Those constables in a position to, dived for cover, drew their weapons and responded as best they could, until they too fell wounded to a man.[25]

The ambushers had anticipated a potential encirclement by responding Crown force units, and quickly dispersed into the night.[26] With the IRA Lewis gun no longer firing across the river, constables from Union Quay barracks promptly turned out and tended to their wounded comrades.[27]

The roughly ten-minute-long engagement left the quay clouded with gun smoke and strewn with wounded policemen.[28] The IRA had mounted their third successful ambush on the Crown forces in the city since the start of the war and inflicted a striking defeat on the RIC.

The Casualties

The ambush on Union Quay was a distinctly one-sided engagement with considerable collateral damage.

The RIC patrol’s full complement of ten policemen were all left wounded, two fatally. Constable Francis Luke Shortall suffered a gunshot wound to the right-hand side of his chest and left thigh, he died three days later in hospital.[29]

Constable Thomas R. Johnston lingered for seventeen days before succumbing to his injuries; secondary haemorrhage from bomb fragment wounds in both legs.[30]

All ten of the RIC patrol were hit and wounded, two died of their wounds.

Three others, Sergeant Patrick O’Driscoll, Constable Patrick Morrissey and Constable J. W. Evans, were also seriously wounded but survived to be financially compensated for their ordeal.[31] The remaining five constables were lucky to walk away with only minor injuries.[32]

Several civilians were also wounded. Pedestrian Kate Bourke was hospitalised with shrapnel in the hip, though an earlier report said that she had received a bullet in the leg; she was subsequently granted £450 in compensation.[33] George Henry Bouchier, who was shot in the knee as he walked along the South Mall towards Parnell Bridge, also received financial compensation albeit more modest.[34]

Two merchant sailors from a Welsh cargo vessel, William Owen and John Hughes, sustained injuries as they unloaded cargo from the bridge itself.[35] Owen was shot in the right arm and neck, while Hughes sustained wounds through both arms and on the scalp.[36] A young girl called Mary Mulcahy was also slightly injured.[37]

In contrast to this carnage the ambushers walked away from the fray without a scratch; of the roughly sixteen Volunteers directly engaged in the fighting not one was even lightly wounded.[38] Given the ferocity of the attack it is reasonable to presume that the Volunteers were directly responsible for all the civilian casualties, yet as we will see through an assessment of the event below, the evidence suggests otherwise.

Contemporary Accounts and Academic Analysis

The Parnell Bridge ambush was an almost flawlessly executed IRA operation and an excellent example of the urban warfare techniques successfully employed by the rebels throughout the conflict. It is however, arguably the most understudied and misunderstood ambush mounted by the Cork No.1 Brigade during the war.

Richard Abbott’s in his book Police Casualties in Ireland 1919-1922, says the police were on patrol ‘when a bomb was thrown at them as they crossed Parnell Bridge’ and claims that the IRA had simply ‘made their attack from the ruins of a public house’, ignoring the scale and tactical ingenuity of the operation.[39]

He does not mention the IRA machine-gun, though it appears in every first-hand account and was a critical factor in the action.[40] Abbott mistakenly says that the patrol was on route to Union Quay when attacked, a simple error also made in a recent academic account of the episode by historians Andy Bielenberg and James S. Donnelly in the entry for Constable Johnston in Cork’s War of Independence Fatality Register.[41]

Both accounts also incorrectly state that the attack took place on the bridge itself.[42] The party had in fact left Union Quay station and were moving along the quay towards City Hall approaching Parnell Bridge when the attack was opened.[43]

Additionally, Abbott claims that ‘Five civilians were also injured by bullets and bomb splinters caused by the IRA’.[44] Mrs. Kate Bourke, was indeed almost certainly injured in the opening IRA grenade assault as she sustained a bad shrapnel wound in the hip and a wound in the arm as she approached the bridge from Anglesea Street, just as the main ambush party launched their assault.[45]

Mary Mulcahy who was slightly wounded in the back, claimed that she was very close to the first two policemen who fell injured, suggesting that she too was caught in the initial IRA bomb attack.[46] However, the most seriously injured civilians, the two sailors hit with bullets on Parnell Bridge, were likely the victims of the police returning fire on the main ambush party.

Newspaper reports state that the sailors were in ‘the line of fire on Parnell Bridge’ yet the IRA were firing in the opposite direction.[47] Indeed most accounts say that the police responded almost immediately to the attack by firing in the direction of the bridge.[48]

Five civilians were wounded in the ambush both by IRA and police fire.

One of the surviving constables, J.B. Cooke, even admitted at the subsequent military inquest to shooting at a group of apparently unarmed civilians as they fled across the bridge.[49] Civilian George Bouchier suffered a bullet wound near his knee when he had been either walking along the South Mall in the direction of Parnell Place or as he had stepped onto the bridge from the South Mall direction.[50]

Either movement would have also placed him in the line of police fire rather than that of the IRA, which was directed in the opposite direction along the quay toward the RIC barracks. While the IRA bore much responsibility for the civilian casualties by launching the attack on a relatively crowded street, RIC fire was directly responsible for the most serious civilian injuries inflicted that evening.

Further, Abbott’s claim that the IRA attack consisted of a single bomb thrown from the ruins of a pub, seriously underestimates the sophistication of the operation.[51] Much to their disappointment, the IRA never possessed grenades powerful enough that one would inflict such damage as Abbott has suggested.

IRA Ambush Tactics

The few ambushes that took place in Cork city during the war have not received adequate attention in the historiography of the period.

An evaluation of the Parnell Bridge ambush based on modern military doctrine and accepted principles of urban combat reveals that, despite certain operational restrictions, the attack was devised, launched, and prosecuted with the professionalism typical of IRA operations mounted in Cork city during the war.

Military analysts identify two types of ambush: (1.) a ‘hasty’ attack mounted on the spot based on opportunism; or (2.) a ‘deliberate’ attack planned in advance like the one in question.[52] As with the Barrack Street ambush three months earlier, Commandant Michael Murphy had personally devised the operation in great detail.[53]

Earlier that day he had summoned selected Volunteers to a meeting at the South Monastery School, where the plan of attack was discussed and individual duties were outlined.[54]

Once the shooting began, the ambushers would have had no way of communicating with each-other over the din of battle, so it was crucial that each man knew his role and strictly adhered to the plan.

Murphy had astutely selected an ideal location to launch the attack.

As an ambush site, Union Quay had many advantageous features. Like many parts of the city, the area was by night left in almost complete darkness as the Corporation had refused to light street lamps in response to the imposition of a rigorous curfew by British military authorities.[55]

The ambush position was well thought out and trapped the RIC patrol in a ‘kill zone’.

This made it almost impossible for those on the patrol to immediately identify the positions of their assailants and react accordingly. Another benefit for the ambushers was that this part of the city contained the ruins of buildings destroyed in the infamous burning of Cork the previous month.[56] These along with the drawbridge infrastructure on Parnell Bridge itself provided excellent cover for the Volunteers in the main ambush party.

In keeping with modern ambush doctrine, the rebels used the landscape to restrict the patrol’s movement once the ambush was opened.[57] The quay itself presented an ideal kill-zone. Moving from the station towards Parnell Bridge the patrol were hemmed in between the south channel of the river Lee to their left and a series of shop fronts to their right.[58] With no side streets between these structures, the ambushed RIC had no route for retreat or manoeuvre.[59]

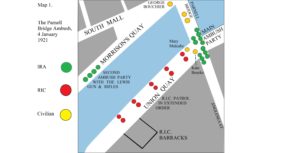

The two ambush parties assumed an ‘L’ shaped formation rather than a linear one, with gunmen to the front and left flank of the patrol. Once the attack had commenced, the patrol’s entire left flank was exposed to the party of rebels across the river armed with the Lewis gun and rifles, while the main ambush party positioned at the junction of Anglesea Street and Union Quay directed their fire down the length of the quay.

This deployment created a crossfire, which ensured that the RIC would be trapped in a ‘kill-zone when the ambush was opened.[60]

The ambushers had hoped that such meticulous planning and preparation would offset certain disadvantages they would inevitably face during the ambush. The foremost of these being weapons and time. As in all conflicts, the terrain impacted the nature of the combat.

The ‘closeness’ of urban engagements placed certain operational restraints on the two IRA battalions operating in the city.[61] Unlike rural units, city fighters had far less time to prosecute attacks, owing to the danger of being surrounded by detachments of the vast Crown force city garrison, who would rush to the scene of fighting in the city in minutes.[62]

The rebels were also disadvantaged by their limited weaponry. Unlike their comrades in the rest of the county, city Volunteers could not carry rifles to an ambush site without immediately identifying themselves to all.

Furthermore, the clandestine transportation of the cumbersome Lewis gun and several rifles in a motor car to the city centre for the operation certainly boosted the ambushers fire-power, the main effort was made by the larger ambush party at the top of the quay armed with only revolvers and grenades.[63]

These easily concealed weapons were ideal for urban combat as it allowed the rebels to move through the streets quickly and subtly before and after an operation.[64] Yet the limited range and power of revolvers meant that this party were inevitably outgunned by their rifle-wielding targets. It was therefore necessary for the rebels to mount the attack at close quarters and crucial that they made the most of the element of surprise and threw everything they had at the patrol in the opening strike.[65]

Standard ambush doctrine specifies that the leader of the attacking party should initiate the assault with the highest casualty producing device at their disposal.[66] This was arguably the IRA’s Lewis gun, which was certainly the highest velocity weapon employed that evening, though the closeness of the main ambush party to the head of the patrol meant that the initial salvo of grenades would undoubtedly cause considerable damage.

By employing both weapons in such quick succession, as to constitute an almost simultaneous assault from both directions, the rebels decimated the patrol’s cohesion.[67] Commandant Murphy claimed that the first burst of the Lewis gun killed seven constables and wounded others; while this is certainly a gross exaggeration, most of the casualties were inflicted in this opening onslaught.[68] The carnage sustained by the RIC in this opening strike was only mitigated by the patrol’s deployment, spread out in extended order along the length of the quay. From this point on, the Lewis gun was trained on the door of the station to block its garrison from turning out, while the riflemen sniped across the river at the pinned-down survivors.[69]

Once the attack had begun, the main ambush party advanced beyond its initial position towards their targets, without going so far as to enter into the line of fire directed by their comrades on the patrol’s flank.[70]

A ten-minute fire-fight ensued in which the rest of the constables fell wounded. If time had allowed, the main attacking force could have capitalised on their temporary tactical advantage and closed in on the remnant of the patrol and brought the ambush to a totally successful conclusion.

Yet the immense numbers of British troops stationed in the city at the time made it critical for ambush parties to promptly break contact during attacks and refuse to engage in prolonged gun-battles. A line of retreat was therefore crucial and on this occasion the IRA had a number of motor vehicles waiting to spirit the ambushers to prearranged safe houses at other parts of the city.[71]

IRA Tactical Shift

The Parnell Bridge ambush represented the last of its type launched by the IRA on the streets of Cork city.

The Parnell Bridge ambush represented the last of its type launched by the IRA on the streets of Cork city. The further reinforcement of the already massive city garrison with additional British Army regiments that spring, made it impossible for Volunteers to again inconspicuously assemble, in relatively large numbers, for an operation in the centre of the city.[72]

However, at the same time ambushes were increasingly prepared for in the suburbs under localised initiative and control[73] and as a result patrols by relatively small Crown force detachments beyond the safety of their fortified barracks, became increasingly rare. Beyond the city limits the Cork No. 1 Brigade flying column also found British convoys were refraining from traversing the main roads in the months that led up to the Truce.[74]

Thus while the IRA found it difficult to pull off more large scale attacks in the spring and early summer of 1921, by posing a credible threat to Crown forces the latter had effectively surrendered control of the city’s suburbs to the IRA.

Conclusion

The Parnell Bridge ambush was an elaborate and ambitious attack, in which the rebels offset their inferior resources through meticulous planning, launching the attack from close quarters and by making the most of the element of surprise.

The resulting clash showed that this amateur guerrilla force had the capacity to knock out an entire reinforced police patrol in the middle of one of the most heavily garrisoned urban centres in the country; which was ringed with fortified barracks and stations, and flooded with thousands of Crown force personnel of various branches.

It was thus a significant milestone on the road to the Truce of July 1921.

References

[1] Hart, P., The I.R.A. & Its Enemies: Violence and Community in Cork 1916-1923 (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1998), p. 106.

[2] Crowley, J., O’ Drisceoil, D., and Murphy, M., eds., Borgonovo, J., associate ed., Atlas of the Irish Revolution (Cork, Cork University Press, 2017), p. 562; Ó Conchubhair, B., ed. Rebel Cork’s Fighting Story, 1916-21, Told by the Men who Made it (Mercier Press, Dublin, 2009).

[3] Borgonovo, J., Spies, Informers and the ‘Anti-Sinn Féin Society’ The Intelligence War in Cork City 1920-1921 (Dublin, Irish Academic Press, 2007), pp. 5 and 126. According to figures provided by Peter Hart, the Cork No. 1 Brigade inflicted more casualties on the Crown forces than the other two Cork brigades combined. See Hart, The I.R.A. & Its Enemies, p. 106.

[4] Kautt, W. H., Ground Truths, British Army Operations in the Irish War of Independence (Sallins, CO. Kildare, Irish Academic Press, 2014), p. 27.

[5] Crowley, O’ Drisceoil, and Murphy, eds., Borgonovo, associate ed., Atlas of the Irish Revolution, p. 379

[6] A nominal city garrison of 4,000 troops, roughly one hundred temporary cadets of the RIC Auxiliary Division and 260 regular RIC operated out of the city during the war. See Crowley, O’ Drisceoil, and Murphy, eds., Borgonovo, associate ed., Atlas of the Irish Revolution, pp. 365 and 379. See also Borgonovo, Spies, Informers and the ‘Anti-Sinn Féin Society’, pp. 41 and 62.

[7] The Cork No. 1 Brigade was divided into nine battalion areas. For a list of attacks mounted by the 1st and 2nd Battalions on Crown forces in Cork city during the war, see ‘Activities in Cork city’ in Military Service Pensions Collections, MA/MSPC/A/1, 1 Cork Brigade, Military Archives Ireland.

[8]. These consist of two RIC killed in the ambush examined in this study, one soldier killed in the Barrack Street ambush of 8 October 1920. See Bureau of Military History Witness Statement 1708, William Barry, National Archives. One Auxiliary fatality in the Dillon’s Cross ambush of 11 December 1920. See Bureau of Military History Witness Statement 686, Seán Healy, National Archives. Along with the deaths of three RIC suffered in the O’Connell Street attack of 14 May 1921. Military Inquiry, Cork Examiner, 20 May 1921, p. 5

[9] Bureau of Military History Witness Statement 1479, Seán Healy, National Archives, p. 55; Bureau of Military History Witness Statement 1547, Michael Murphy, National Archives, p. 28-29

[10] Cork Examiner, 5 January 1921; Cork Constitution, 5 January 1921.

[11] Monthly Weather Report of the Meteorological Office, Issued by the Authority of the Meteorological Committee. Forty-Sixth Year. Vol. XXXVIII. January, 1921; Cork Constitution, 5 January 1921.

[12] Cork Examiner, 5 January. 1921; Cork Constitution, 5 January 1921.

[13] Cork Examiner, 5 January 1921; The Freeman’s Journal, 5 January 1921.

[14] Bureau of Military History Witness Statement 1707, Patrick Collins, National Archives, p. 9.

[15] Cork Constitution, 5 January 1921; Cork Examiner, 5 January 1921.

[16] Military Court of Inquiry Report, War Office, 35/158A/21; County Inspector’s Confidential Monthly Report for January 1921, Cork, (City and East Riding), The British In Ireland Series, CO 904/114.

[17] Military Inquest, WO, 35/158A/21; Military and Police Compensation Claims, Report of Cork Borough Sessions, Cork Examiner, 25 February 1921

[18] Military Inquest, WO, 35/158A/21. For the Parnell Bridge ambush, IRA Commandant Michael Murphy assembled some of the city’s top gunmen into what was essentially an elite 2nd Battalion ambush unit. See BMH WS 1547, Michael Murphy, NA, p. 35. These included one of the most highly regarded city fighters Tadhg Sullivan who led the main ambush party at the junction of Union Quay and Parnell Bridge. See O’Suilleabhain, M., Where Mountainy Men Have Sown (Anvil Books, Kerry, 1965), p. 114; Cork Examiner, 20 and 23 April, 1921. Manning the brigade’s invaluable Lewis gun during the ambush was ex-British army gunner Christopher Healy. Military Service Pensions Application, 7614, Christopher Healy, National Archives; Military Service Pensions Collection, MA/MSPC/A/1(E)2, Brigade Activity Reports, E Company, 2 Battalion, 1 Cork Brigade, Military Archives Ireland.

[19] These men did not constitute a permanent unit but officers in their respective companies brought together specifically for the ambush in question; as individual fighters they typically operated as part of a smaller local Active Service Unit (ASU). See Bureau of Military History Witness Statement 1521, Michael Walsh, National Archives, p. 11; Bureau of Military History Witness Statement 1707, Patrick Collins, National Archives, p.5. While the flying column served as the chief offensive arm for rural IRA brigades, ASUs assumed this role in Cork city. See Statements regarding activity in Period 5. in Military Service Pension Application, 59728, Margaret Newlove Lynch, National Archives; A twelve-man, full-time, city-wide ASU was established at the beginning of 1921. See Bureau of Military History Witness Statement 1584, Patrick A. Murray, National Archives, pp. 21-22; Bureau of Military History Witness Statement 1656, Daniel Healy, National Archives, p. 14. Each of the city’s sixteen companies also deployed at least one local ASU. See Bureau of Military History Witness Statement 1741, Michael V. O’ Donoghue, National Archives, pp. 84-85.

[20] Military Court of Inquiry Report, War Office, 35/152/39; BMH WS 1521, Michael Walsh, NA, p. 12; Freeman’s Journal, 6 January, 1921, p. 5; Cork Examiner, 5 January 1921; Outrages Against the Police, Weekly Summaries, Cork city, report on the ambush on Parnell Bridge, The British In Ireland Series, CO 904/150.

[21] BMH WS 1521, Michael Walsh, NA, p. 12; Cork Examiner, 5 January 1921; Freeman’s Journal, 6 January, 1921, p. 5; Outrages Against the Police, report on the ambush on Parnell Bridge, CO 904/150.

[22] Military Inquest, WO, 35/158A/21; Report of Cork Borough Sessions, Cork Examiner, 25 February 1921, p. 7.

[23] See Florence O’ Donoghue’s article on the ambush, Ms. 31,301 (4), National Library of Ireland. See also Report of Cork Borough Sessions, Cork Examiner, 25 February 1921; BMH WS 1521, Michael Walsh, NA, p. 12.

[24] BMH WS 1707, Patrick Collins, NA, pp. 9-10.

[25] CI Report for January 1921, CO 904/114; Freeman’s Journal, 5 January 1921; Cork Examiner, 5 January 1921; Cork Constitution, 5 January 1921; Report of Cork Borough Sessions, Cork Examiner, 25 February 1921.

[26] BMH WS 1707, Patrick Collins, NA, pp. 9-10; Cork Constitution, 5 January 1921.

[27] Cork Constitution, 5 January 1921; Freeman’s Journal, 5 January 1921; Bureau of Military History Witness Statement 869, P. J. Murphy, National Archives, pp. 22-23.

[28] The length of time given for the engagement range from between five minutes, see Cork Examiner, 5 January 1921, and fifteen minutes, see BMH WS 1521, Michael Walsh, NA, p. 13.

[29] See Military Inquest, WO, 35/158A/21. For details about Constable Francis Shortall, see Abbott, R., Police Casualties in Ireland 1919-1922 (Mercier Press, Dublin, 2000), p. 181. Shortall’s widow was awarded £2,250 compensation, while his father and sister received £1,250. See Report of Cork Borough Sessions, Cork Examiner, 25 February 1921.

[30] Before his death, twenty-year-old Constable Thomas R. Johnston supported his large family in Cavan. He had been a porter in an Edinburgh hospital, before joining the RIC. His father, who was still working as a labourer at the time, was awarded £1,000 compensation. See Report of Cork Borough Sessions, Compensation Claims, Cork Examiner, 10 May 1921, p. 3. See also Abbott, Police Casualties in Ireland 1919-1922, p. 181

[31] These three constables received financial compensation for their injuries. Sergeant Patrick O’Driscoll was awarded

£350, Constable Patrick Morrissey received £130 and Constable J. W. Evans received £80. See Report of Cork Borough

Sessions, Cork Examiner, 25 February 1921. See also report in Irish Independent, 26 February, 1921, p. 3.

[32] The lightly injured were constables James Gardiner and John B. Cooke, see Military Inquest, WO, 35/158A/21 and

WO 35/152/39, along with Constables Chambers, Elliot and John Ahern. See Cork Constitution, 5 January 1921 and

Cork Examiner, 5 January 1921.

[33] See Kate Bourke’s compensation claim in Report of Cork Quarterly Sessions, Cork Examiner, 7 May 1921 and Cork Examiner, 5 January 1921, p. 5.

[34] Cork Examiner, 5 January; Report of Cork Borough Appeals, Cork Examiner, 15 July 1921, p. 3.

[35] Cork Examiner, 5 January 1921; Cork Constitution, 5 January 1921; Freeman’s Journal, 5 January 1921.

[36] Cork Examiner, 5 January 1921; Cork Constitution, 5 January 1921; Freeman’s Journal, 5 January 1921.

[37] Cork Examiner, 5 January 1921; Freeman’s Journal, 5 January 1921.

[38] BMH WS 1547, Michael Murphy, NA, p. 35; BMH WS 1707, Patrick Collins, NA, p. 10; BMH WS 1521, Michael Walsh, NA, p. 13.

[39] Abbott, Police Casualties in Ireland 1919-1922, p. 181; Only one contemporary account claims that a single IRA grenade caused all of the police casualties. See Outrages Against the Police, report on the ambush on Parnell Bridge, CO 904/150; This is contradicted by all other accounts including other RIC reports. See CI Report for January 1921, CO 904/114.

[40] Abbott, Police Casualties in Ireland 1919-1922, pp. 180-181; Cork Examiner, 5 January 1921; Cork Constitution, 5 January 1921; Freeman’s Journal, 5 January 1921.

[41] Abbott, Police Casualties in Ireland 1919-1922, pp. 180-181; Andy Bielenberg and James S., Donnelly, Cork’s War of Independence Fatality Register, The Irish Revolution, RIC Constable Thomas R. Johnston, http://theirishrevolution.ie/1921-3/#.XXJ5VWZ7nIU (accessed on 5 Aug 2018).

[42] Abbott, Police Casualties in Ireland 1919-1922, pp. 180-181; Bielenberg and Donnelly, Cork’s Fatality Register, RIC Constable Thomas R. Johnston (accessed on 5 Aug 2018).

[43] Only two contemporary sources claim that the patrol was on route back to Union Quay when ambushed. See Cork Constitution, 5 January 1921 and Freeman’s Journal, 6 January 1921. These are contradicted by all first-hand accounts. See Military Inquest, WO, 35/158A/21 and 35/152/39; Report of Cork Borough Sessions, Cork Examiner, 25 February 1921; BMH WS 1521, Michael Walsh, NA, p. 12; BMH WS 1707, Patrick Collins, NA, p. 9; BMH WS 1547, Michael Murphy, NA, p. 35.

[44] Abbott, Police Casualties in Ireland 1919-1922, p. 181.

[45] Report of Cork Quarterly Sessions, Cork Examiner, 7 May 1921; Cork Examiner, 5 January 1921.

[46] Freeman’s Journal, 5 January 1921; Cork Examiner, 5 January 1921.

[47] Cork Examiner, 5 January 1921; Cork Constitution, 5 January 1921.

[48] Freeman’s Journal, 6 January 1921, p. 5; Report of Cork Borough Sessions, Cork Examiner, 25 February 1921.

[49] See Constable J.B. Cooke’s testimony at Military Inquest, WO, 35/158A/21.

[50] Cork Examiner, 5 January 1921; Cork Constitution, 5 January 1921; Freeman’s Journal, 5 January 1921.

[51] Abbott, Police Casualties in Ireland 1919-1922, p. 181.

[52] Ranger Handbook. SH 21-76 United States Army. Rangers Training Brigade. (United States Army Infantry School Fort Benning Georgia. February 2011), Chapter. 7.

[53] BMH WS 1708, William Barry, NA, p. 4.

[54] BMH WS 1521, Michael Walsh, NA, p. 12.

[55] Hart, The I.R.A. & Its Enemies, p. 6.

[56] Cork Examiner, 5 January 1921; Freeman’s Journal, 5 January 1921.

[57] Ranger Handbook, Chap. 7.

[58] Guy’s City Almanac Directory 1921, Postal Directory Cork City and Suburbs, p. 524.

[59] Guy’s City Almanac Directory 1921, Postal Directory Cork City and Suburbs, p. 524.

[60] Ranger Handbook, Chap. 7.

[61] Kautt, Ambushes and Armour, p. 189.

[62] Kautt, Ambushes and Armour, p. 189.

[63] Outrages Against the Police, report on the ambush on Parnell Bridge, CO 904/150; BMH WS 1521, Michael Walsh, NA, p. 12; Cork Examiner, 5 January 1921; Freeman’s Journal, 6 January 1921, p. 5.

[64] Kautt, Ambushes and Armour, p. 187.

[65] Kautt, Ambushes and Armour, p. 187.

[66] Ranger Handbook, Chap. 7.

[67] Cork Examiner, 5 January 1921.

[68] BMH WS 1547, Michael Murphy, NA, p. 35; Military Inquest, WO, 35/152/39, p. 4; Cork Examiner, 5 January 1921.

[69] BMH WS 869, P. J. Murphy, NA, pp. 22-23; Cork Examiner, 5 January 1921.

[70] Ranger Handbook, Chap. 7; BMH WS 1707, Patrick Collins, NA, pp. 9-10.

[71] Cork Constitution, 5 January 1921; BMH WS 1707, Patrick Collins, NA, pp. 9-10; The ambush party with the Lewis gun and rifles fled the scene in the motor car they arrived in and made their way to a safe-house in Ballincollig several miles outside the city see BMH WS 1547, Michael Murphy, NA, p. 35.

[72] Crowley, O’ Drisceoil, and Murphy, eds., Borgonovo, associate ed., Atlas of the Irish Revolution, p. 365

[73] Bureau of Military History Witness Statement 1675, Jos. O’Shea, National Archives, p. 14; BMH WS 1479, Seán Healy, NA.

[74] Kautt, Ambushes and Armour, p. 194; Borgonovo, Spies, Informers and the ‘Anti-Sinn Féin Society’, p. 98; Bureau of Military History Witness Statement 1669, Stephen Foley, National Archives, p. 10.