The ‘State will Perish’: Comparing the Elections of 1932 and 2020

By John Dorney

In the wake of the February 2020 Irish elections, former Sinn Féin leader Gerry Adams compared that party’s success (it scored 25% of the vote and 37 out of 160 seats) as comparable to the ‘last Saturday election’ in December 1918, when Sinn Féin won 73 out of 105 Irish seats and went on to declare Irish independence in the First Dáil.

But in fact, a much better comparison is the 1932 election in which Eamon de Valera’s Fianna Fáil tasted electoral victory and entered government for the first time.

‘A slightly constitutional party’

It was just nine years after the end of the Irish Civil War, in which de Valera had been the political leader of the defeated anti-Treaty faction. De Valera himself had been among over 12,000 anti-Treatyites imprisoned in the conflict, only being released in 1924.

His close colleague in Fianna Fáil, Frank Aiken, had been the anti-Treaty IRA Chief of Staff who called an end to the conflict by ordering IRA units to ‘dump arms in May 1923.

Fianna Fáil broke with Sinn Fein in 1926 but remained closely associated with the IRA.

For a time, de Valera and his colleagues in (anti-Treaty) Sinn Féin[1] had refused to recognise the Irish Free State or take their seats in its parliament and between 1922 and 1926 had organised an underground ‘republican government’ with de Valera as its President. It even had its own parliament ‘Comhairle na dTeachtaí’. [2]

Many of those who held positions as ministers in this underground government – including Frank Aiken and Sean Lemass – also held senior positions in the IRA. The guerrilla army had never disarmed and still intended, when the time was right, to overthrow the Free State by force of arms.

De Valera was too much of a realist to spend his political career in the wilderness, running a fantasy government with no authority, however. He and his colleagues left Sinn Féin in1926 owing to that party’s refusal to abandon abstentionism and formed Fianna Fáil. Most of the senior figures in the new party such as Aiken and Lemass resigned their positions in the IRA, but at lower level there remained a great deal of crossover between the two organisations.

The early Fianna Fáil was, as Sean Lemass famously said, a ‘slightly constitutional party’; if they could achieve their goals ‘by the present [peaceful] methods we will be very pleased’, he said in the Dáil in 1929, ‘but we will not confine ourselves to them’. [3]

The early Fianna Fáil was, as Sean Lemass famously said, a ‘slightly constitutional party’; if they could achieve their goals ‘by the present [peaceful] methods we will be very pleased’, he said in the Dáil in 1929, ‘but we will not confine ourselves to them’. [3]

Fianna Fáil espoused a populist and economic nationalist programme as well as its goal of severing the remaining links between the Irish Free State and Britain. But the IRA at this time was very influenced by left wing ideas and several of its leaders, notably Peadar O’Donnell were sympathetic to Soviet communism.

The IRA had not renounced violence. In 1931 alone they carried out six assassinations (two Gardaí; a detective and a Superintendant, and four alleged informers).[4] It was estimated that they had just under 5,000 members in 1931 with not inconsiderable dumps of weapons, including 850 rifles and 29 machine guns as well as many handguns and some explosives. [5]

Their opponents in the government of Cumman na nGaedheal (pro-Treaty victors in the 1922-23 Civil War) saw the IRA as a grave threat to the state’s security and de Valera’s Fianna Fáil as their enablers. In October 1931 the government passed a Public Safety Act, temporarily suspending jury trials and banning a host of republican organisations.

But it was economic crisis occasioned by the onset of the Great Depression as much as the legacy of the Civil War that worried the government. There was high unemployment and a housing shortage and due to the Depression in the United States, emigration there was no longer an attractive option to relieve social tensions.

Minister Patrick McGilligan warned that ‘falling [government] revenue, increasing demands for services, falling prices and increased unemployment and the absence of emigrants’ remittances’, posed serious risks of public disorder.

This combined with the resurgence of both Fianna Fáil and the IRA would make it, he told his colleagues, ‘sheer madness to operate repressively throughout a miserable and poverty stricken 12 months’, before the next general election was due. And so an election was called for February 1932. [6]

The ‘gunmen are voting for Fianna Fáil’

In the run up to general election of 1932, ‘Free State election news’ warned its readers that ‘your state, the order which it has fostered and encouraged, the faith of your children which it protects, courtesy of its laws against communism and immoral teaching, is in danger’… it is your duty to help the government party to eliminate all the danger of Spanish Republic in Ireland’. [7]

Garda Commissioner Eoin O’Duffy warned the government of a ‘concrete link’ between the IRA and communism. ‘If the Soviet comrades are not dealt with, he warned, ‘the state will perish’. O’Duffy himself tried to sound out senior military figures about a coup to stop Fianna Fáil coming to power, but was largely rebuffed. [8]

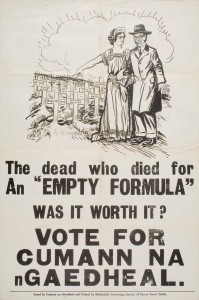

Even more bluntly, a poster for the ruling Cumman na nGaedheal party urged voters, ‘the gunmen are voting for Fianna Fáil, the communists are voting for Fianna Fáil. How will you vote?’.[9]

Cumman na nGaedheal denounced Fianna Fail as ‘gunmen and communists’ in 1932, but de Valera’s party won the election.

De Valera, countered that the way to head off the danger of communism was for ‘people anxious to get work will get work, that people entitled to decent houses get houses’. [10]

Oddly enough even the normally conservative Irish Times agreed with the Fianna Fáil leader. It too abhorred communism, but argued that such urgings, ‘must be futile so long as 4,830 tenement houses shelter 25,320 families in the heart of Dublin. It is almost a miracle that communism has not flourished aggressively in that hideous soil. What an irony it would be if the Free State, having throttled sedition is killed by the cost of houses’. [11]

The Fianna Fáil constitution said that its aims were to ‘secure the unity and independence of Ireland as a Republic’ and the restoration of the Irish language, but also to ‘make the resources and wealth of Ireland subservient to the needs and welfare of all the people of Ireland’. [12]

Fianna Fáil won the February 1932 election with over 45% of the vote, ahead of Cumman na nGaedheal who polled 35%, and de Valera’s party entered government with support from the Labour Party. A snap election called in January of the following year gave Fianna Fáil an overall majority.

While about a third of the electorate had supported the anti-Treaty Republicans in the 1923 election, directly after the Civil War, Fianna Fáil’s transformation to the party of government was as much to do with offering housing, welfare and land redistribution as nationalist objectives such as removing the Oath of allegiance to the British monarch and recovering the naval bases Britain had kept under the Treaty. Let alone the much more difficult objective of a united Ireland.

While about a third of the electorate had supported the anti-Treaty Republicans in the 1923 election, directly after the Civil War, Fianna Fáil’s transformation to the party of government was as much to do with offering housing, welfare and land redistribution as nationalist objectives such as removing the Oath of allegiance to the British monarch and recovering the naval bases Britain had kept under the Treaty. Let alone the much more difficult objective of a united Ireland.

In this sense it had much in common with the Sinn Féin surge in 2020, which was far more about housing, rents and public services than a desire for Irish unity. Comparisons are easy to draw also with Cumman na nGaedheal rhetoric in 1932 and Fine Gael’s in 2020, when Taoiseach Leo Varadkar compared Sinn Féin’s policies on housing with the socialist regimes of East Germany and Venezuela.

New masters

It was by no means inevitable, in 1932 that the organs of the Free State, especially the Garda and the Army would obey the new government. After all they had spent their formative years putting down the ‘irregulars’ on behalf of the Free State.

One of de Valera’s first actions in power was to legalise the IRA and free their prisoners. Frank Ryan, a leading left wing IRA member, who was among those freed, declared later in 1932 that, ‘while we have fists, boots and if necessary guns to use, there will be no free speech for traitors’ in Cumman na nGaedheal.[13]

Rioting between the IRA and the pro-Treaty Army Comrades Association (later renamed the National Guard or the Blueshirts) became commonplace as both attempted to break up each others’ meetings.

Just before they left office, the Cumann na nGaedheal Minister for Defence ordered Army Intelligence to ‘destroy by fire’, all Intelligence reports, Secret Service Voucher and Military Court Records which ‘contain information that may lead to loss of life’, before the Department of Defence was handed over to their one-time Civil War foes in Fianna Fáil. [14]

Despite serious tensions in 1932-33, the leaders of the army and police obeyed their new masters.

In this sense, 1932 was far more fraught than 2020. While many mainstream politicians in Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael bridle at thought of a Sinn Féin Minister for Justice, given that party’s ties with the Provisional IRA, there is no street fighting between partisans of rival parties nor does anyone propose legalising an armed organisation that has as its goal the overthrow of the state.

In the 1930s, as it happened, things went far more smoothly than might have been expected. Aside from Eoin O’Duffy, who was sacked as Garda Commissioner and who went on to lead the Blueshirts (and then briefly, Fine Gael) there was no purge of the officer corps of either the Garda or the Army by Fianna Fáil. And by and large, those in the army and police who had fought the Civil War against the ‘Irregulars’ loyally obeyed them when they came to power by legal means.

De Valera’s government banned the Blueshirts in 1933, by passing a bill prohibiting the wearing of uniforms, and abolished the Senate too when it tried to block the bill. It also recruited about 200 IRA men in an armed police auxiliary ‘Broy’s Harriers’, recruited others into an army Volunteer Reserve and opened military pensions to anti-Treaty veterans of the Civil War. [15]

But it also began imprisoning IRA members in 1934 and in 1936, as that organisation continued to carry out shootings, banned it too. The left wing of the IRA was marginalised and mostly left it to set up the Republican Congress in 1934, but in face of denunciation by the Catholic Church, the far left made little further progress in 1930s Ireland.

By 1936 there was no longer talk, even from the most hysterical anti-Fianna Fáil sources, of de Valera as the ‘Irish Kerensky’ opening the way for social revolution.

‘Not mad’

De Valera succeeded in breaking the link between the Irish state and British monarchy and in 1938, in securing the return of the Treaty ports from Britain, which allowed Ireland to be neutral in the Second World War. By such means, most, though not all, anti-Treaty republicans were brought into the mainstream of peaceful politics.

This, rather than corruption of state institutions by illegal organisations is likely to be the result too of Sinn Féin’s entry into power. Like Fianna Fáil, if threats by extremist republican groups to them continue, Sinn Féin are likely to turn on the ‘dissidents’ with all the power at their disposal.

Fianna Fail did build housing and increased social services, but by the end of the 1930s had become effectively a centre right party.

How did Fianna Fáil in government do in social and economic terms? Certainly Fianna Fáil of the 1930s considerably upped public spending and provision of social services. Whereas the Cumman na nGaedheal government had built around 14,000 houses in in its decade in power, Fianna Fáil built about 12,000 every year between 1932 and 1942. They also introduced unemployment assistance and the widows and orphans’ pension in 1935. [16]

But while employment rose somewhat, emigration continued apace. Under Fianna Fáil’s protectionist policies, Irish domestic industry did grow, but exports fell by some 25%. This was due to de Valera’s ‘economic war’ (punitive tariffs) with Britain, provoked by his refusal to pay back land annuities owed to Britain under the Treaty. Many large farmers in particular blamed the de Valera government for ruining their trade. [17]

But by the 1940s Fianna Fáil had become a centrist, in many ways a conservative, party. The same may eventually happen with Sinn Féin.

Even the employers’ federation Ibec has said that Sinn Féin’s proposals are ‘not mad’. Brian Hayes of the Banking Federation said, ‘If people were talking about radical change to investment policy and free movement of capital, that would be a worry. But I don’t think they are’. While Dan McCoy of Ibec argued (in an echo of 1932) that the state service did need investment; “The public sector is too small for the size of the private sector … We agree there needs to be an allocation of resources towards issues that affect people’s everyday lives, like housing.”

Brexit and the north

There is however one major difference between Fianna Fáil of 1932 and Sinn Féin of 2020 and that is that the latter is an all Ireland party. Indeed it could be argued that modern Sinn Féin has its origins in Northern Ireland. Its firm goal remains a united Ireland. By contrast, de Valera’s party, despite consistent rhetoric about Irish unity, never organised in the North, despite many pleas from nationalists there to do so.

Unlike Fianna Fail, Sinn Fein may be in government both in the North and South.

So while Fianna Fáil made much of partition when it was negotiating with Neville Chamberlain’s government in 1938 and 1939 on how to end the economic war and on the return of the Treaty ports, it was understood that it was only speaking for the 26 county state.

In negotiations in the present era, both inside Northern Ireland and with the British government regarding Northern Ireland’s status after Britain leaves the European Union, the Irish government has been a third force, separate both from the British and Northern Irish parties.

With Sinn Féin in government in the Republic and in the power sharing government in the North, this would no longer be possible. Which, with Northern Ireland’s status still uncertain in a post Brexit future, could have unpredictable consequences.

References

[1] The Sinn Féin party was founded in 1905 by Arthur Griffith. It was adopted by veterans of the 1916 Easter Rising and in 1917 committed itself to an Irish Republic. It won the 1918 general election in Ireland and declared Irish independence in January 1919. In 1922 it split over the Anglo Irish Treaty with a slight majority of its elected representatives voting for the settlement with Britain. Pro and anti-Treaty Sinn Féin factions fought the 1922 election with the pro-Treaty faction again coming out on top. In the election of August 1923, just after the Civil War, pro-Treaty (formerly Sinn Féin) candidates ran as a new party Cumman na nGaedheal, while anti-Treaty candidates ran under the title ‘Republican’. But thereafter it was the anti-Treatyite that took and held the name ‘Sinn Féin’.

[2] Donnacha O Beachain, The Destiny of Soldiers, Fianna Fáil Irish Republicanism and the IRA (2009) p.26.

[3] O Beachain Destiny of Soldiers p.99

[4] Hoare Frank Ryan, p.75-77

[5] Brian Hanley The IRA 1926-1936 (2002) p.220. This total of weapons is similar to the arsenal of the Provisional IRA prior to its decommissioning of weapons in 2005 according to CAIN estimates. Though the 1930s IRA membership was much larger.

[6] O Beachain, Destiny of Soldiers, p.121

[7] John Regan The Irish Counter Revolution, Treatyite Politics and Settlement in Independent Ireland, 1921-1936. (2001) p.280 The Spanish Republic is a reference to the anti-clerical government of the Spanish Republic, declared in 1931.

[8] Fearghal McGarry, Eoin O’Duffy, A Self Made Hero, (2005) p.182

[9] O Beachain p126

[10] Dermot Keogh, in James Hogan, Revolutionary, Historian and Political Scientist, Ed Donncha O Corrain (2000) p.68

[11] Adrian Hoar, In Green and Red, The lives of Frank Ryan (2005) p.88.

[12] O Beachain Destiny of Soldiers p.48.

[13] Hoar, Frank Ryan, p.95

[14] Military Archives, CD 334 Destruction Order 7 March 1932

[15] Dermot Keogh, Twentieth Century Ireland, Nation and State, p.84

[16] JJ Lee, Ireland 1912-1985, Politics and Society, (1993) p.193

[17] Lee, Ireland 1912-1985 p.190