The Truth in the News: The Irish Press Cartoons of Victor Brown

By Barry Sheppard

By Barry Sheppard

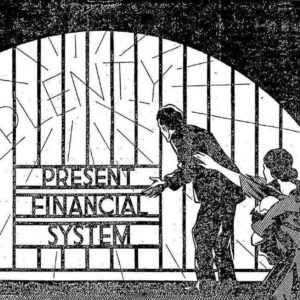

The depiction of a family, in rags and despairing at their present situation was designed to show that the ordinary people of Ireland were no better off under a decade of Cumann na nGaedheal rule than they were under the British.

The sight of this family, struggling under this administration, just out of reach of the promised land of plenty helped stir emotions and strike a chord with those who wanted political change.

While it is an obvious cliché to say a picture is worth a thousand words, the editorial cartoon can have a tremendous impact upon the readership of the popular press in any number of countries. Historian of cartoons, Thomas Milton Kimnetz argued that they are ‘an excellent method for disseminating highly emotional attitudes’.[1] This argument holds true, especially in times of war, revolution and upheaval.

Victor Brown’s political cartoons captured the message of the Irish Press and of Fiann Fail in the lat 1920s and early 1930s.

In an Irish context, this has been shown in the work of Felix Larkin on the Freeman’s Journal cartoonist Ernest Forbes,[2] and in James Curry’s study of Ernest Kavanagh, the illustrator in the radical Irish Worker publication.[3] These studies cover what we now term the Irish revolutionary period, and show the genius of the artists in capturing complex political themes.

Indeed, as recent commemoration events have shown the actions of one hundred years ago still have the power to elicit highly emotional responses, one can guess what impact representations of these events in the popular press had at the time. What can be said, however about periods following revolution? Feelings were still raw, yet society was attempting to move on from the upheaval and bloodshed of the late 1910s and early 1920s. How did the artist capture these themes, in a period when political life was still precarious, and the destination still uncertain?

This article will examine the cartoons of Irish Press illustrator, Victor Brown which appeared in the first years of the publication, from 1931-1933. Covering themes of Irish identity, the continued influence of Britain in Irish affairs, and the thorny issue of the Oath of Allegiance, they helped promote Fianna Fail’s political policies to the Irish public via this brand new news source.

Fianna Fail and the rise of the Irish Press

In a fractured society, divided by bitter civil war memories and a partitioned island, many questions were left unanswered and ambitions unrealised. Ideals which had bounded men and women together in revolution were now either adulterated or dismissed altogether.

In a fractured society, divided by bitter civil war memories and a partitioned island, many questions were left unanswered and ambitions unrealised. Ideals which had bounded men and women together in revolution were now either adulterated or dismissed altogether.

One side of the civil war, anti-treaty republicans were licking their wounds and staring down the barrel of electoral oblivion. Faced with a decision of continuing on his path of futility or adapting to the new political dispensation, their leaders had to grapple with difficult decisions, not only to rejoin the political race, but to revive the radicalism which had initially inspired young men and women into action.

This radicalism was now in many cases dormant among the post-civil war Irish population, who had been ground down by violence and upheaval.

In order to achieve their aims, a number of things were needed. A certain break from the recent political past was urgently required. So too was a vehicle to disseminate ideas which would point to a new future. This path was embarked upon when Eamonn de Valera and his loyalists departed Sinn Fein in March 1926 after ‘the Long Fellow’s’ proposed motion on the Oath of Allegiance was defeated.[4] De Valera saw the futility of Sinn Fein’s stance and ‘lost no time in building up an alternative power base’, attracting what Lyons called the ‘more moderate Sinn Fein adherents’.[5] This group of political dissidents would form Fianna Fáil later that year.

Fianna Fail needed a newspaper to counteract what they saw as a hostile press.

Despite their moderation in relation to the Sinn Fein rump, they still had to present the newly-formed Fianna Fáil as a radical alternative to the dominant Cumann na nGaedheal which under the stewardship of W.T. Cosgrave, Kevin O’Higgins et al, had began to stagnate. However, in order to present their radical programme to the Irish public, a national newspaper was needed. The new publication needed to reach those who had been defeated a decade earlier and those who had grown weary of the politics which had dominated since the conclusion of the civil war.

Many within the republican movement had long been aware of the need for some kind of national newspaper which would carry their viewpoints. As early as 1922 de Valera noted that the propaganda against them was overwhelming. He lamented “we haven’t a single daily newspaper on our side, and only one or two small weeklies”.[6]

Besides the launch in 1927 of the weekly Fianna Fáil newsletter The Nation, this situation wasn’t rectified until the publication of the Irish Press newspaper in 1931. The Irish Press would prove an invaluable tool to disseminate Fianna Fáil policies and party propaganda, as well as an increased emphasis on native language, games, and industry. The paper was a tremendous success, and has been recognised as an important factor in the elections which brought Fianna Fáil to power.

Victor Brown and the disseminating the Republican message

A small, but integral part of this new publication was the editorial cartoons by Press cartoonist Victor ‘Bee’ Brown. Brown was born in Nuneaton, Warwickshire in 1900. The son of a soldier in the British Army, he had spent a period of his childhood in Ireland while his father was stationed in the country.

A small, but integral part of this new publication was the editorial cartoons by Press cartoonist Victor ‘Bee’ Brown. Brown was born in Nuneaton, Warwickshire in 1900. The son of a soldier in the British Army, he had spent a period of his childhood in Ireland while his father was stationed in the country.

He returned to Ireland in his twenties, studying Irish art, and contributing to numerous book illustrations and magazines, as well as his own vast catalogue of paintings. A friend of W.B. Yeats, he had a tremendous interested in Celtic art forms.

While it is unclear as to how he came to be on the books of the new Irish Press newspaper, his impact in the early years of the publication is undeniable. His work encapsulated much of Fianna Fáil’s policies in the early years, as well lampooning their political rivals in easily-digestible depictions in prominent sections of the paper. Under the expert guidance of first Irish Press editor, the renowned Republican Frank Gallagher, Brown’s cartoons provided an effective political weapon in the lead up to the 1932 and 1933 general elections.

The Irish Press launched on 5th September 1931. From the outset the paper was keen to stress its Irish Republican credentials.

The Irish Press launched on 5th September 1931. From the outset the paper was keen to stress its Irish Republican credentials. The mother of two Irish Republican icons Pádraig and Willie Pearse ceremonially switched on the paper’s printing press, with the picture appearing on the front page of the first edition. The overt republicanism of the newspaper and by association the Fianna Fáil party concerned many in the political establishment. Much had occurred in the years from the foundation of Fianna Fáil to the establishment of the Press, events which had heightened political tensions in the new state, most notably the assassination of Kevin O’Higgins by the IRA in 1927.

Fianna Fáil’s connections with the IRA were widely reported on in these years. As well as alleged links to the illegal armed organsiation, Fianna Fáil’s dubious political relationship to the state was a bone of contention among established politicians. Kevin Boland, speaking in relation to the first Fianna Fáil Ard Fheis, held in November 1926, notes: ‘The only real difference with Sinn Fein was in the matter of tactics. There was no acceptance of the legitimacy of the Free State […] It was merely a question of recognising the de facto situation for practical reasons’.[7] This stance naturally caused great concern among the Irish political elites.

The party’s ambiguous relationship with constitutional politics had a large question mark hanging over it at the best of times. However, a quip by future Fianna Fáil leader Sean Lemass about being a ‘slightly constitutional party’[8] during a Dáil debate on prisoners in 1928 ruffled many political feathers and is still an instantly-recognisable quote to this day. Key figures in the party such as Lemass and Frank Aiken had close associations with the IRA, an organisation which had ‘never disarmed and still intended, when the time was right, to overthrow the Free State by force of arms’.[9]

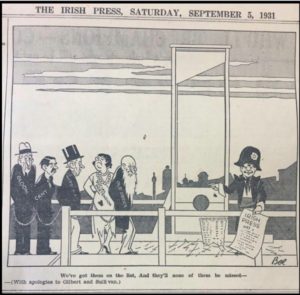

It was against this backdrop of political distrust and continued IRA activity that the Irish Press hit the newsstands on Saturday, 5th September 1931.

It was against this backdrop of political distrust and continued IRA activity that the Irish Press hit the newsstands on Saturday, 5th September 1931.

Far from mollifying concerns over intentions to overthrow the still-young state, the newspaper published an incendiary cartoon which hinted at overthrowing the old order by revolutionary means.

A depiction of a scene from the French Revolution shows a line of people representing the ‘old order’ in the Irish state on their way to the guillotine. A smiling executioner, holding a parchment, points to the line of the condemned, exclaiming “We’ve got them all on the list, and they’ll none of them be missed”.

This was a bold move for a publication not yet one day old. Outside of what could be viewed as its intentions for certain sections of Irish society, the depiction of what was classed as the old order, figures in top hats and refined clothing, separate from the ‘real’ Irish people was a theme which would continue throughout Brown’s run as Press cartoonist.

This was perhaps, reflective of prevailing attitudes at the time, certainly among those in Fianna Fáil circles. Sean Lemass, as Bryce Evans notes, would often caricature the party’s opposition as toffs in top hats, a stance which was a ‘class criticism with Anglophobic undercurrents’.[10]

Painting the opposition as the ‘other’ or alien to Ireland was a strong theme in Brown’s cartoons, ironically so, given his own background. Nevertheless, it was integral to painting Fianna Fáil on the right side of Irish society. This is something to which we will return. However, being on the right side of society at the present time was something, being on the right side of history was an altogether more important issue. Indeed, one position could not be consolidated without the long story of the other being told, and told correctly.

The importance of carrying on a separatist tradition which spanned generations was a story which Fianna Fáil and the Irish Press had to get right if they were to portray themselves as the rightful inheritors of the tradtion, and Brown’s cartoons were hugely important in framing this story. From the outset the tone of the Irish Press signalled that the paper and Fianna Fáil were on an election footing.

The wrongs of the recent past were important to emphasise, and this is something which Brown did with aplomb. However, framing the story of the more distant past was integral to presenting where Irish society now found itself.

‘The Perpetual Flame’

This is perhaps best illustrated by an offering which appeared in time for Republican Easter commemorations in late March 1932. Entitled ‘The Perpetual Flame’, the cartoon featured the figure of Libertas standing aside the perpetual flame which carried within each of its flickers a date of past rebellions in Ireland from 1641 through to 1922.

This is perhaps best illustrated by an offering which appeared in time for Republican Easter commemorations in late March 1932. Entitled ‘The Perpetual Flame’, the cartoon featured the figure of Libertas standing aside the perpetual flame which carried within each of its flickers a date of past rebellions in Ireland from 1641 through to 1922.

This cartoon placed Fianna Fáil as the true inheritors of a long and varied Irish Republican tradition. While Brown was the artist, there is little doubt that Frank Gallagher played an important role in its construction.

Gallagher had a strong pedigree in the newspaper industry. A trained journalist by the time he joined the Irish Volunteers in the autumn of 1917, he worked for a number of publications, including the Cork Free Press. However, it was working alongside Desmond Fitzgerald, and then Erskine Childers in the Irish Bulletin during the War of Independence ‘that his talents were given a proper showcase’.[11]

It was in this publication; in the lead up to the 1921 truce that Gallagher wrote on the ‘permanent tradition’ of Irish Republicanism, stating that the movement had ‘its roots deep in the past and representing the permanent tradition of the Irish race’.[12]

This is unquestionably represented in the Easter 1932 cartoon of ‘the Perpetual Flame’ which streamlines a long and complicated history to produce a simplified narrative. While this was simply if expertly done within the pages of the Irish Press, it is not to say that this wasn’t a commonly-held belief among the wider Irish Republican community.

Identifying the enemy

Being on the right side of history means little if one could not successfully identify ‘the other’, that is the enemy of your viewpoints and beliefs. While the ‘enemy’ in this case was Britishness, the view was that it was the remnants of that regime which was causing the lingering disharmony in the Irish state (and the island, with partition being another British-introduced problem).

Everything from dirty electoral money to fashion sense indicated the damage that British influence was still having upon Irish society. Many of Brown’s cartoons in this period deal with these themes of Irishness, ‘the other’ and ‘the other’s’ Irish political allies.

Everything from dirty electoral money to fashion sense indicated the damage that British influence was still having upon Irish society. Many of Brown’s cartoons in this period deal with these themes of Irishness, ‘the other’ and ‘the other’s’ Irish political allies.

From the publication of the first Irish Press edition, the paper and party were on an election footing. Anything which could be used to discredit Cumann na nGaedheal was eagerly pounced upon. Countless cartoons in the latter part of 1931 and early 1932 on the lead up to the general election emphasised just how reliant Cumann na nGaedheal were on a variety of interested parties, ranging from the British Government to the Orange Order.

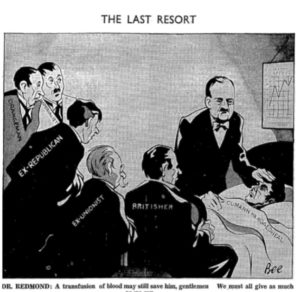

The following brief selection of these cartoons is typical of the longer themes of Brown’s work in the Press. On 24 November 1931, the paper portrayed Cumann na nGaedheal as a spent force on its deathbed surrounded by interested parties whose own survival depended upon Cumann na nGaedheal pulling through. Among the concerned onlookers is the ‘Orangeman’ the ‘Imperialist’ the ‘Ex-Unionist’ and ‘Ex-Republican’, while at the head of the bed, checking the patients temperature is the recent Cumann na nGaedheal recruit Captain William Redmond.

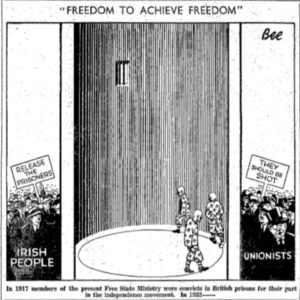

In early January 1932, a matter of weeks before the dissolution of the sixth Dáil, the Press carried a daring front page cartoon on the matter of still-incarcerated Republican prisoners. Taking a direct swipe at the famous quote of Michael Collins ‘the freedom to achieve freedom’ it applies it to those still in prison at the behest of the state.

In early January 1932, a matter of weeks before the dissolution of the sixth Dáil, the Press carried a daring front page cartoon on the matter of still-incarcerated Republican prisoners. Taking a direct swipe at the famous quote of Michael Collins ‘the freedom to achieve freedom’ it applies it to those still in prison at the behest of the state.

However, it provides us with a stark ‘them vs. us’ example of how divisive Irish politics was at the time.

On one side of the prison wall, banded together are the ‘Unionists’ adorned with top hats and monocles calling for the prisoners to be shot. While on the other side stands ‘the Irish People’ calling for the prisoners’ release. This is perhaps as clear an example as can be found of Brown’s work which plays on the notion of the ‘Unionist’ or ‘Ex-Unionist’ as against the goals of Fianna Fáil, and by extension, the Irish people.

An election footing

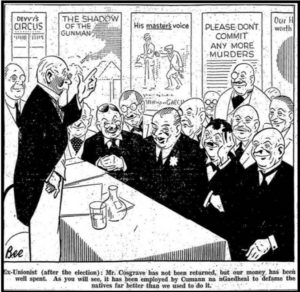

In the final stretch of the 1932 election campaign the attention of the Irish Press was firmly on ‘ex-Unionists’ (a target from the paper’s first edition). The front page cartoon on 15th February 1932, the day before that year’s election highlighted the Unionist interests who had supposedly bankrolled Cumann na nGaedheal’s campaign.

This campaign had resulted in some of the party’s most memorable election posters. These striking posters, still regularly referenced today were extremely professional, and were indicative of how Irish elections were now fought; something which Ciara Meehan has impressively highlighted.

An interesting point which Meehan has made in relation to this form of election propaganda is that when Fianna Fáil attempted incorporate imagery into their posters it wasn’t as creative or professional as their arch-rivals.[13]

Meehan makes a very valid point here. However, Fianna Fáil despite being late to the game were now being very creative in their election propaganda within the pages of the Irish Press (their cartoons parodied several of Cumann na nGaedheal’s famous 1927 election posters during the 1932 campaign).

Meehan makes a very valid point here. However, Fianna Fáil despite being late to the game were now being very creative in their election propaganda within the pages of the Irish Press (their cartoons parodied several of Cumann na nGaedheal’s famous 1927 election posters during the 1932 campaign).

In this particular sketch they used a selection of Cumann na nGaedheal’s election posters to highlight what they felt would be that party’s electoral failure.

The central figure in the cartoon, one of the ‘ex-Unionist’ which had bankrolled Cosgrave’s party, points at the posters in the background, stating “As you can see, it (our money) has been employed by Cumann na nGaedheal to defame the natives far better than we used to do it”.[14]

Felix Larkin notes that the use of the term ‘the native’ used by the Irish Press here is ‘calculated to paint Irish Protestants in a bad light’. Interestingly, he claims that readers of the Irish Press ‘could be relied upon to take offence at the presumption of racial superiority that it betrays’,[15] indicating that readers of the newspaper were comfortable having their own personal prejudices reinforced by their newspaper of choice.

This, of course has echoes of debates around popular press outlets in the present day. Editorial cartoons can, as Tim Ellis argues, ‘simultaneously influence and reflect social and political attitudes’.[16] Not only was the Press attempting to attract new readers, it was also, naturally playing to its and Fianna Fáil’s existing electoral base.

Ownership of the past

Alongside claiming ownership of violent revolts of Ireland’s past, the paper sought to claim the Irish cultural past. The period referred to as the Irish cultural revival of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries influenced many that took part in the revolutionary movement.

The Irish Press presented Fianna Fail as the inheritors of the Irish nationalist narrative: its political and cultural heir.

Furthermore, it was a hugely important era in relation to the construction of an Irish identity which impacted subsequent generations. Covering, art, literature, sport and language, it offered people an alternative to what some viewed as the aping of the predominant British culture and identity of the time. It was perhaps obvious that those behind the Irish Press would also seek to co-opt that aspect of Irish Republican identity, and present themselves as the inheritors of those ideals.

A popular feature of the Irish Press over the years was its Irish language section. Indeed, in the first edition of the newspaper in September of 1931 it carried a front page feature addressed as a ‘message to the nation’. This was penned by the founder of the Gaelic League and future President of Ireland, Douglas Hyde, who implored the nation to speak Irish and ‘awaken nationality’.[17]

Arguably the Press had stronger associations with the native language than that of its competitors. This is reflected in what Mark O’Brien highlights as the editorial objective of the paper, ‘Do cum Gloire De Agus Onora na hEireann’ (for the glory of God and the honour of Ireland).[18]

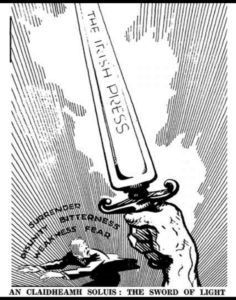

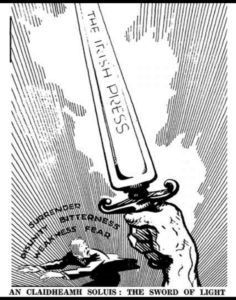

A prime demonstration of the Press as custodian of the cultural and linguistic past came on the occasion of the newspaper’s first anniversary, 5 September 1932. In this edition the Brown cartoon claimed the paper was ‘An Claidheamh Soluis’ (The Sword of Light).

A prime demonstration of the Press as custodian of the cultural and linguistic past came on the occasion of the newspaper’s first anniversary, 5 September 1932. In this edition the Brown cartoon claimed the paper was ‘An Claidheamh Soluis’ (The Sword of Light).

This was, of course the name of the organ of the Gaelic League from 1899 (eventually discontinued in 1932 after several name changes), it was for a time under the editorship of Republican icon Padraig Pearse. Under Pearse’s guidance the publication had, in a number of editorials ‘insisted on the primary importance of the Gaelic revival over all other kinds of ‘national work’’.[19]

While the Irish Press was no doubt more receptive to Irish language concerns than the competition, adapting the ambitions of An Claidheamh Soluis and Douglas Hyde wholesale would have been economic suicide for the publication. Nevertheless, association with a hugely-recognisable brand name from the cultural revival carried with it great political capital.

The Oath of Allegiance

Two of the biggest burning issues of the day were, naturally tackled in Brown’s cartoons. What was known as the ‘Economic War’ of 1932-38, and the hated (from an anti-treaty point of view) Oath of Allegiance to the British monarch, both received the Irish Press treatment. Fianna Fáil had strongly indicated its intention to abolish the Oath of Allegiance, should it win power in 1932.

Two of the biggest burning issues of the day were, naturally tackled in Brown’s cartoons. What was known as the ‘Economic War’ of 1932-38, and the hated (from an anti-treaty point of view) Oath of Allegiance to the British monarch, both received the Irish Press treatment. Fianna Fáil had strongly indicated its intention to abolish the Oath of Allegiance, should it win power in 1932.

The Oath was perhaps the most divisive part of the 1922 Constitution of the Irish Free State. This Oath contained a guarantee of faithfulness to King George V and his heirs and successors by law makers in the Irish Free State.

This was highly controversial and had rankled with those who rejected the Treaty back in 1922. It had, as we have noted, hastened de Valera’s departure from Sinn Fein in early 1926. Now, with a renewed vigour and crucially, a strong mandate they sought to expunge this highly controversial clause.

While the Economic War took up many column inches, not just in Irish newspapers, the issue extended beyond Brown’s time as cartoonist in the Irish Press. For that reason, and the fact that to show Brown’s work on the Economic War would need at least two further articles it should be left aside for now.

A further issue which hovered abstractly in the background was partition. However, this was not really reflected in Brown’s work at the Press, save for a strange warning from the ghost of Abraham Lincoln on the dangers of a divided Ireland.[20] Nonetheless, Irish Press cartoons, like Fianna Fáil for the main, sidestepped the partition problem to deal ‘with the much narrower issue’ of the Oath.[21]

A further issue which hovered abstractly in the background was partition. However, this was not really reflected in Brown’s work at the Press, save for a strange warning from the ghost of Abraham Lincoln on the dangers of a divided Ireland.[20] Nonetheless, Irish Press cartoons, like Fianna Fáil for the main, sidestepped the partition problem to deal ‘with the much narrower issue’ of the Oath.[21]

The Oath was one of the main topics on the campaign trail of 1932, and during countless public meetings its abolishment was raised, alongside the justification for Fianna Fáil’s constitutional gymnastics in entering the Dáil in 1927.[22] The message continued to be hammered home right to the line.

In a last-ditch appeal to the Irish electorate on the morning of the 1932 election, 16th February the Irish Press appealed to the working man (women rarely featured in any prominence in these depictions) to do their duty that day. The depiction is of a representative of the electorate removing boulders in the way of the ‘National Express’ train. Tellingly, the one which the electorate figure is attempting to move is that of the Oath.

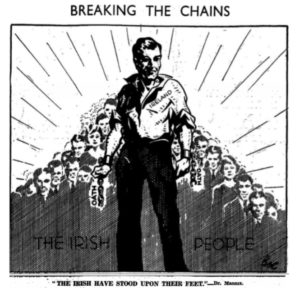

One of the most striking cartoons which dealt with the removal of the Oath came in the wake of Fianna Fáil’s electoral victory, on the 25 March 1932 entitled ‘Breaking the Chains’. The powerful image of Ireland in chains (representing the Oath in this instance) has been replicated many times since.

The masculine figure breaking free of the chains is backed up by a pyramid of faces representing the Irish people, and is bolstered with a quote from the celebrated and controversial Irish Australian prelate Archbishop Daniel Mannix.

The masculine figure breaking free of the chains is backed up by a pyramid of faces representing the Irish people, and is bolstered with a quote from the celebrated and controversial Irish Australian prelate Archbishop Daniel Mannix.

Mannix was staunch Irish Nationalist and a close associate of the celebrated leader of Fianna Fáil, even accompanying him on part of his famous 1919-1920 tour of America. His belief in de Valera and his ability to deliver freedom to Ireland ‘never wavered’[23] and was often to offer guidance and words of encouragement in important moments.

One such example was the night before de Valera was on the cusp of power in 1932, when he communicated in a telegram ‘May God uphold and guide Ireland and you in these difficult days’.[24] Mannix’s nationalist leanings were well known in Ireland and would have carried some weight. Therefore including a proclamation of this kind at the foot of the illustration demonstrated the shared goals of Mannix and Fianna Fáil when it came to taking the British King out of Irish society.

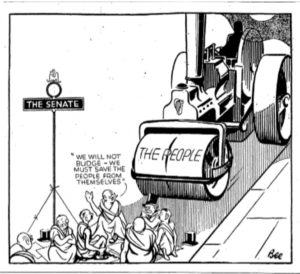

The progress of the 1932 Bill to remove the Oath was stymied by the upper house of the Irish legislature, the Seanad. This caused much strife in political circles. During the Seanad debate on the Oath removal Bill Cumann na nGaedheal senator Sean Milroy, in a speech which lasted over two hours[25] dismissed the controversy around it as a mere ‘storm in a teacup’ and stated that to remove the Oath now would be ‘folly of the greatest magnitude’.[26]

However, it was far from a storm in a teacup for those who had a decade prior picked up arms against their former comrades. After the Bill’s passage was paused both Fianna Fáil and the Irish Press went on the attack against those who had pushed against it. On the 4th of June 1932, the Press again called on Brown to caricature those who identified as Unionists as the upper class who were standing in the way of the people. They were depicted as aloof senators in Roman garb sitting in the path of a steamroller representing the Irish people.

When de Valera went back to the people after calling a snap election in January of 1933, he called out the actions of the Seanad in stifling Fianna Fáil and the Irish people’s constitutional ambitions.

When de Valera went back to the people after calling a snap election in January of 1933, he called out the actions of the Seanad in stifling Fianna Fáil and the Irish people’s constitutional ambitions.

Addressing a crowd of 30,000 ‘enthusiastic supporters’ in Dublin in on the 8th January he exclaimed that the Bill ‘was held up by the Senate, but in the election you can pass it in spite of the Senate. Once this election is over and we are returned to power the Bill has only to be sent to the Senate and whether they like it or not it becomes law’.[27]

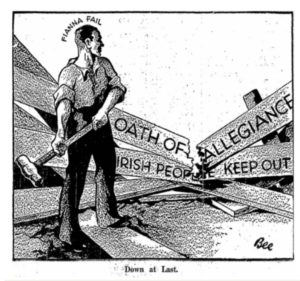

And so it came to pass. Once the Bill was reintroduced it became law in May of 1933. The Irish Press was understandably jubilant and produced a memorable cartoon on 6 May 1933 to celebrate the victory. The picture, entitled ‘Down at Last’ shows what appears to be an agricultural worker representing Fianna Fáil with a sledgehammer breaking through a barrier which states ‘Oath of Allegiance – Irish People Keep Out’.

The figure was far removed from the elderly, out of touch Senators which featured in the previous Brown attack on the Seanad. While those figures were elderly, dressed in Roman finery, and out of touch with the Irish people, this figure embodied that which Fianna Fáil held dear, a youthful, masculine and muscular rural worker which had broken through the metaphorical glass ceiling which held back Irish ambitions of nationhood.

The figure was far removed from the elderly, out of touch Senators which featured in the previous Brown attack on the Seanad. While those figures were elderly, dressed in Roman finery, and out of touch with the Irish people, this figure embodied that which Fianna Fáil held dear, a youthful, masculine and muscular rural worker which had broken through the metaphorical glass ceiling which held back Irish ambitions of nationhood.

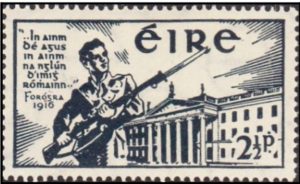

In truth this was one of the last memorable cartoons of Victor Brown’s short run in the Irish Press. His work seemed to feature less and less, with one of the last commissions appearing on the second anniversary of the Irish Press debut.

His reasons for departure are unclear. However, the years in which Brown was employed by the paper were chaotic and ‘were beset by industrial disputes of one kind or another’.[28] Therefore, the instability may have led him to seek steady employment elsewhere.

However, it seems Victor Brown was never short of work outside of his stint in the Irish Press, and his work took him both inside and outside of Irish republicanism, indicating that he was first and foremost and artist for hire, rather than someone who had a deep ideological conviction for the brand of Irish nationalism which the Irish Press was known for.

He is well known for his stamp design commemorating the 25th anniversary of the Easter Rising. However, his talents reached beyond this.

He is well known for his stamp design commemorating the 25th anniversary of the Easter Rising. However, his talents reached beyond this.

In the aftermath of his departure from the Press he designed the wedding cake for the marriage of the Duke of Kent in November 1934.[29] Further commissions followed including one on the Irish father of the Argentine Navy, Guillermo Brown (no relation), as well as many other commissioned pieces.

Victor Brown died in Dun Laoghaire in 1953. His work in the Irish Press was integral to the paper’s success in those first couple of years, and covered many issues which were the burning political topics of their day. At times divisive, in line with the direction he received from the paper’s editor; they unquestionably helped revive political themes which had lain dormant in vast sections of Irish society over the previous number of years.

Listen to Barry discuss Victor Brown and the Irish Press here:

References

[1] Thomas Milton Kemnitz, ‘The cartoon as a historical source’ in The Journal of Interdisciplinary History, iv, no. 1 (1973), pp 84-5.

[2] Felix. M. Larkin, Terror and Discord: The Shemus Cartoons in the Freeman’s Journal, 1920-1924 (Belfast, 2009).

[3] James Curry, Artist of the Revolution: The Cartoons of Ernest Kavanagh, 1884-1916 (Dublin, 2012).

[4] Bryce Evans, Sean Lemass – Democratic Dictator (Cork, 2011), p. 49.

[5] F.S.L. Lyons, Ireland Since the Famine, (Glasgow, 1974), p. 495.

[6] Tim Pat Coogan, De Valera: Long Fellow, Long Shadow (London, 1993), p. 430.

[7] Kevin Boland, The Rise and Fall of Fianna Fáil (Dublin, 1982), p. 22.

[8] Dail Eireann Debate – Wednesday 21 March, 1928, Vol. 22, No. 14.

[9] John Dorney, ‘The State Will Perish’: Comparing the Elections of 1932 and 2020: https://www.theirishstory.com/2020/02/12/the-state-will-perish-comparing-the-elections-of-1932-and-2020/#.XpWjeflKjIU

[10] Bryce Evans, Sean Lemass: Democratic Dictator (Cork, 2011) p. 80.

[11] Graham Walker, ‘’The Irish Dr Goebbels’: Frank Gallagher and Irish Republican Propaganda’ in Journal of Contemporary History, Vol. 27, No. 1 (Jan., 1992), pp. 149-165.

[12] The Irish Bulletin, 4 July 1921.

[13] Ciara Meehan, ‘Politics Pictorialised: Free State Election Posters’ in Mel Farrell, Jason Knirck and Ciara Meehan (eds.) A Formative Decade: Ireland in the 1920s (Kildare, 2015), p. 30.

[14] Irish Press, 15 Feb. 1932.

[15] Felix M. Larkin ‘Carson’s Abandoned Children: the southern Irish Protestant as depicted in Irish cartoons, 1920-1960’ in Ida Milne and Ian d’Alton (eds) Protestant and Irish: The minority’s search for place in independent Ireland (Cork, 2019).

[16] Tim Ellis . ‘Women, gender and masculinity in Irish political cartoons, c.1922-1939’ (MA Thesis, 2016), p. 1.

[17] Irish Press, 5 Sept. 1931.

[18] Mark O’Brien, De Valera, Fianna Fáil and the Irish Press (Dublin, 2000), p. 35.

[19] Bryan Fanning, Irish Adventures in Nation-Building (Manchester, 2016), p. 27.

[20] Irish Press, 18 February 1933.

[21] Jim Maher, The Oath is Dead and Gone (Dublin, 2011), p. 296.

[22] Donegal News, 9 January, 1932.

[23] Joe Broderick, ‘De Valera and Archbishop Daniel Mannix’ in History Ireland, Vol. 2, Issue 3, (Autumn 1994).

[24] Jim Maher, The Oath is Dead and Gone, p. 277.

[25] Irish Press, 26 May, 1932.

[26] Seanad Eireann Debate – Wednesday 25th May 1932, Vol. 15, No. 13.

[27] Irish Press, 9 Jan. 1933.

[28] David Robbins, The Irish Press 1919 -1948: Origins and Issues (MA Thesis, 2006), p. 8.

[29] Evening Herald, 29 Nov. 1934.