Podcast: Ireland and the Middle East in the British Empire

Cathal Brennan and John Dorney discuss the parallels between Ireland the British ruled Middle East after the First World World War. First broadcast on the Irish History Show.

The British Empire in the middle east dated back to the 19th century, when trading and naval bases were established on the southern rim of the Arabian peninsula to safeguard British trade.

It later encompassed Egypt which British troops occupied in 1882, essentially to protect their investment in the Suez Canal. Although Egypt remained formally part of the Ottoman Empire for the next thirty years, in reality it was ruled by the British via compliant Egyptian monarchs.

But it was after their victory over the Ottoman Empire in the First World War that the British really expanded their presence in the region. As early as 1916, in the Sykes-Picot agreement, the British and the French had decided to divide up the middle east between them, with the British taking Palestine and Mesopotamia (modern Iraq) as ‘mandates’ under the League of Nations, while the French were to take what became Lebanon and Syria. The British also created what amounted to a client state in Transjordan (modern Jordan).

There are many connections and parallels between the British Empire in the middle east in the 1920s and 30s and the Irish experience in the same period.

In fact the plan originally envisaged the partition of Turkey as well, but determined resistance by Turkish nationalists under Kemal Ataturk eventually put paid to this notion. In addition the British maintained a strong informal control over oil-rich Persia (modern Iran), via control of its oil and transport infrastructure.

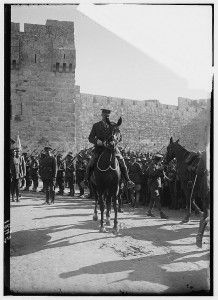

The consolidation of the British controlled territories in the middle east occurred at the same time as the struggle for independence in Ireland and this forms the basis for our discussion in the podcast.

One parallel between the two situations is that post War promises of self determination, especially by US President Woodrow Wilson, were disappointed in both places. In Ireland Home Rule, promised since 1912 had not been delivered, and in the middle east, the newly subject peoples were deemed not yet to be ready for self government.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, this led to armed resistance. Ireland’s War of Independence raged from 1919-21, while Egypt saw a major nationalist uprising in 1919 and Iraqis mounted a sustained armed revolt in 1920. There was also violent unrest in Palestine in 1921-22 as the Arab inhabitants rioted against the influx of Jewish settlers – the British also having promised Palestine as a ‘national home for the Jewish people’ in the Balfour Declaration of 1917.

One upshot of this for Ireland was that British troops could not be deployed there in large numbers until late 1920 and 1921 as many were tied up in Egypt and Iraq. Many more were serving as occupation troops in places as diverse as Germany, Turkey, Upper Silesia in Poland and another contingent had been sent to aid the Whites in the Russian Civil War.

One reason why the Black and Tans were recruited is that many regular troops were tied up in 1920 dealing with revolts in the middle east.

This might in part explain why Lloyd George’s government chose to recruit paramilitary police corps – the Black and Tans and Auxiliaries – to put down the ‘Irish Rebellion’ rather than regular troops. Nevertheless, not a few units, for instance the Manchester Regiment, served in both Iraq and Ireland.

There is some parallel between British reprisals in Ireland and those elsewhere. In general though, as we discuss, British suppression of Arab revolts in the middle east was far harsher and more indiscriminate than what took place in Ireland – commonly using aerial and artillery bombardment for instance against civilian villages. Figures such as Sir John French the Lord Lieutenant and Nevil Macready, the British Army’s commandeer in Chief, wanted such methods used in Ireland, but were overruled.

But another very interesting parallel that we talk about is the British use of self government as a means of ending troublesome conflicts. The Anglo-Irish Treaty and the partition of Ireland were seen by the British as a means of extracting themselves from a difficult and politically costly situation, granting self government while still retaining their vital strategic interests.

And the same can very largely be said of British policy in the middle east in the interwar period. In 1922, for instance, British formally granted independence to Egypt, but retained a military garrison, control over Egyptian foreign policy and over the Suez Canal and Sudan.

In Iraq, also in 1922 the British signed a treaty, granting Iraq self government, but again, retaining military, naval and air bases as well as a 75 year concession to the newly discovered oil fields around Mosul for a British company.

In neighbouring Persia (Iran) the British concluded a treaty in 1919, whereby they not only kept a majority interest in the oil fields but also retained control over the country’s railways and over training the Persian military.

These parallels could suggest a very cynical use by the British of self government as a cover for Empire, both in Ireland and in the middle east. But it is also possible to view these treaties as, in Michael Collins’ famous phrase, ‘freedom to achieve freedom’ for the countries concerned.

Persia repudiated the 1919 treaty as early as 1921. Both Egypt and Iraq, like Ireland in 1938, secured major new concessions in terms of self government in the 1930s, though formal independence had to wait until after 1945 and British influence lingered for several decades thereafter.

This left Palestine, which was, throughout the British mandate period, disputed between Arab and Jewish inhabitants, prompting some comparison with Northern Ireland and its two rival communities. One direct connection, as Sean Gannon has pointed out on the Irish Story, is that many members of the disbanded Royal Irish Constabulary, including the Black and Tans and Auxiliaries, were sent to Palestine in 1922 where they formed the backbone of the Gendarmerie. Their commander was Henry Tudor, the ‘Chief of Police’ in Ireland from 1920-21.

The British put down an ‘Arab Revolt’ in 1936-39, but in the later 1940s, found themselves fighting Zionist guerrillas also, once the British had set their face against further Jewish immigration. They departed precipitously in 1948, sparking open war between what became the state of Israel and the surrounding Arab states.

This conversation does not pretend to be the final word on the comparisons, both direct and indirect, between interwar Ireland and the middle east, but it can hopefully open up further discussion in the future. Listen below.