Tom Barry and the Road from Mesopotamia to Kilmichael

By John Dorney

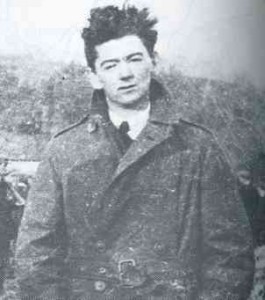

In 1915, aged 17, Thomas Bernadine Barry enlisted in the Royal Field Artillery in Cork, as he recalled in his memoir, ‘for no other reason than that I wanted to see what war was like, to get a gun, to see new countries and to feel a grown man’.[1]

He was sent to Mesopotamia (modern Iraq), where he fought, operating an artillery piece, against the Ottoman Turks for two years. In 1919 he returned to Ireland and in November of that year, spoke on behalf of ex servicemen and attended the Armistice Day commemoration, where the Union flag was raised.

But by the following November, he was in command of an IRA guerrilla column that wiped out a patrol of fellow Great War veterans; the Auxiliaries of C Company, at the townland of Kilmichael, between Dunmanway and Macroom. For reasons that still spark a heated debate today, in some circles, no prisoners were taken by the IRA that day.

How did Tom Barry, the British soldier, policeman’s son and proud Great War veteran, became Tom Barry the legendary IRA column leader?

Barry never showed any remorse about what he did at Kilmichael. Applying for an Irish military pension in 1940, for his IRA service, and appealing angrily against what he considered to be an insufficient award, he wrote to the Pensions Board in his typical bombastic manner:

I was the first Army officer to tackle the dreaded Auxiliaries at Kilmichael and I smashed their power and broke forever the morale of those mercenaries who were especially enlisted for their fighting qualifications and their bloodthirstiness. I did it with twenty two riflemen not one of whom had ever fired a shot in action previously… I left eighteen of them [the Auxiliaries] dead…and burned their lorries. And their comrades never waited for us once after that’. [2]

He went on to say,

‘I was the most successful fighting officer the Army had from 1919 onwards. The men I commanded never had a defeat or a failure and I killed more of the enemy at, say, two of my engagements, Crossbarry and Kilmichael, with only a Brigade column, than any two other divisions combined’.[3]

How did Tom Barry, the British soldier, policeman’s son and proud Great War veteran, became Tom Barry the legendary IRA column leader, who revelled in the killing of his enemies?

Great War

Barry’s motives for joining the British Army were, certainly as he portrayed them, fairly apolitical, one of over 150,000 Irishman who volunteered for British forces in the First World War. That his father had been an RIC constable might have counted against him in the eyes of purist republicans or separatists, but not to many beyond those circles.

He came from a ‘respectable’ family and was fairly well educated – he had spent a couple of years at Mungret’s boarding school in Limerick.

His war record was nothing spectacular. He saw action as an artillery gunner, against the Turks in Mesopotamia at Kut, Samara and Fallujah, was raised to the rank of bombardier (artillery equivalent of corporal) but reverted back to ‘gunner’ at his own request in 1916.

Barry served as an artilleryman in the Mesopotamian campaign from 1916-18.

That year, according to Barry’s memoir, when he heard the news of the Easter Rising in Dublin, it gave birth to his national consciousness.

But if this was so, it seems to have impacted little on his life in the British Army. While he had a few disciplinary issues, which resulted in him being given ‘field punishment’, there was no hint that he had rebelled against the Army on nationalist grounds, like say, the Connaught Rangers’ mutiny in India in 1920. His discharge papers noted that he was ‘sober’ and a ‘good hardworking man’.[4]

Some biographical sketches report that he was gassed in the war, at Ypres in 1915, according to Peter Hart and at Basra in 1916 according to Meda Ryan. [5] But Barry never served on the Western Front at Ypres and the Turks in Mesopotamia did not possess chemical weapons.

According to Gerry White, he was awarded a disability pension, on his discharge in May 1919, for malaria and ‘Disordered Activity of the Heart’. White suggests that this referred to ‘soldier’s heart’ or Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) as it would be termed today.[6]

But it may also have been an actual heart condition, perhaps brought on by extreme stress. Barry was hospitalised with chest pains after the Kilmichael ambush in 1920 and just before the start of the Irish Civil War in June 1922.

There was nothing in particular in his war record that marked him out as a guerrilla leader or a small unit infantry tactician of any kind. As an artilleryman, was he very unlikely to have experienced in the War, the kind of close-quarters, small unit fighting that he was to excel at in Ireland.

The ex-Servicemen’s Association

In his memoir, Guerilla Days in Ireland, (published in 1949) Barry passes over, almost without comment, the period from his return to Cork in mid 1919 until he began training the Third Cork Brigade of the IRA in September 1920.

He claims that he returned from the war a convinced separatist, reading everything he could about the independence movement and had to go ‘on the run’ from May 1920 due to British suspicion of him. However, the records from 1919 tell another story.

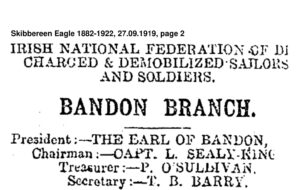

Back in Bandon, he joined the National Federation of Discharged and Demobilised Sailors and Soldiers (NFDDSS), or the ‘ex-Servicemen’s association’ as it was colloquially known, indeed he served as Secretary to the Bandon branch, which was headed by the Earl of Bandon, a prominent landowner and local unionist. He addressed war veterans at a meeting in Cork city on November 8, 1919, calling for veterans to be given preferential treatment in government employment in recognition of their service, and attended Armistice Day in Bandon three days later.[7]

On his return from the war, Barry served as secretary of the ex-Servicemen’s association in Bandon and applied for a job in the British Civil Service

He was, at this time studying business and law at a night college and apparently hoped to gain employment in the civil service. Gerry White’s research tells us that in 1919, a “T. B. Barry” failed to pass an examination for the position of “Male Clerk, Ministry of Labour, Reconstruction Scheme, Ireland Division”. Another entry on his record, dated February 2nd, 1920, reads: “Asks Indian Posting”’.[8]

In other words, Barry at this time appeared to be a loyal veteran, who wanted only to be rewarded by the British state for his service, and actively sought further British employment, either in the civil service at home or in India.

According to this reading, it was his rejection, being left, unemployed, on the scrapheap by an ungrateful government, that turned him into a rebel.

Barry’s version, presented in a long tortuous pension application in 1940, which has only recently been released, however, tells a very different story.

IRA infiltrator?

Barry states that as soon as he returned from the War in 1919, he approached the Volunteers (or IRA) in Cork, and asked to join. And this appears to be true.

Florence O’Donoghue, of Cork No 1 Brigade, in the city, testified at Barry’s pension hearing in 1940 that Barry approached him to join the Brigade in the summer of 1919. While Barry told them openly that he had served in the British Army, owing to this, O’Donoghue stated, ‘We naturally had hesitations’ in taking him. Eventually O’Donoghue told him to apply to the Third Brigade, in Bandon, where he was from.[9]

Barry maintained in his pension application in 1940 that in 1919 he was infiltrating the ex-Servicemen’s association on IRA orders.

And here, according to Sean Buckley, who at that time was the Intelligence Officer of Third Brigade, Barry was secretly enrolled in the Bandon Company in August 1919, and employed doing intelligence work, infiltrating the ex Servicemen’s Association. According to Buckley:

‘The principal intelligence work he did for me was that he was connected with the ex servicemen’s association and at that particular time, the ex servicemen’s association was being made use of by the Imperialist crowd to be used as a sort of buffer between the growing republican movement and the British forces. I remember there was a Convention here in Dublin and he was a member I think of the Munster Executive of ex-servicemen. ‘ [His job was] to find out what was the attitude of the heads of this organisation in Ireland to the Republican movement and what their attitude would be as regards the force, the ex servicemen’.[10]

Barry himself stated that he gave a full report on the ex-Servicemen’s association to Charlie Hurley, one of the commanders of Third Brigade, particularly with regard to whether the war veterans might be mobilised against the spreading Republican insurrection.

Barry also claimed to have met British officers in the bars and hotels of Bandon, where he elicited from them details of IRA suspects and prospective raids. He recalled that when he was afterwards suspected of leaking information to the IRA, ‘I had a bit of a hiding, after that I was no good on Intelligence’. This, he recalled, was in October 1919, after which he stated that he started training IRA companies in the use of rifles.

This then, appears to present us with a neat solution. Barry was simply masquerading as a loyalist in the ex-Servicemen’s association, when he was really already enrolled in the IRA and carrying out their orders in 1919.

Contradictions

There is certainly some truth in this. Several IRA veterans swore to this version in Barry’s pension hearing, including Sean Buckley, the Bandon Company captain Michael Herlihy and Brigade commander at the time, Tom Hales. It seems like a safe bet that Barry was indeed passing information to Sean Buckley in late 1919.

But there are two major problems with this story of secret IRA membership in 1919. The first is that it does not match the chronology of Barry’s actions. He spoke at a veterans’ meeting on November 8, 1919 and attended the Armistice Day ceremonies on the 11th, at a time when, according to his later testimony, he had already resigned from NFDDSS, and as late as June 10 1920, he was still acting as secretary at the meetings of the Bandon branch of the ex Servicemen’s association.[11]

The second major problem with the narrative that Barry was training IRA units in musketry in early 1920, is that the men who ran the Third Brigade flatly denied it at his pension hearing in 1940. Flor Begley, in 1920 the commander of 1 Battalion of the Third (West Cork) Brigade, was asked if he knew Barry in 1919.

I knew him.

Did you know if he was or was not a member of the organisation in 1919?

He was not.

Other IRA veterans flatly denied that Barry joined the organisation before August of 1920.

When shown Barry’s statement that he had joined the Volunteers in 1919, Begley appears to have been dismayed. ‘I am sorry he made such statements. That is not true.’[12]

Liam Deasy, who was from Bandon and on the Brigade Staff, was ‘definite’ that although Barry, ‘was in touch with Sean Buckley, for how long I cannot say’, he was not taken into the IRA until August of 1920, when he was taken on as a training officer.

Barry was, according to Deasy, first interviewed in a hotel in Cork city by Charlie Hurley and Ted O’Sullivan, then presided over a training camp in September 1920, before being put in charge of the Brigade’s active service unit, or ‘flying column’ in October of that year.[13]

Barry might have demonstrated the use of a rifle to some IRA men in early 1920 and he might, as he asserted at his pension hearing, have been involved with riots and scuffles with British troops in Bandon, but it seems certain than he was not sworn in to the Volunteers until August of 1920.

Wavering loyalties?

Reading between the lines a little, we can say that in early 1920, Barry was probably wavering in his loyalties. His futile attempts to join the Volunteers in 1919 and his association with Sean Buckley clearly show that he had Republican sympathies by this time.

At the same time, he did not formally apply to join the Third Cork Brigade until July 1920 and was not accepted until August. In the meantime he did not sever his connections with the ex Servicemen’s association in Bandon until June 1920, at the earliest.

The Pension Board in 1940 wanted to know why, if he was already committed to the Republican struggle, he was not at any of the numerous attacks carried out on Crown forces in West Cork prior to October 1920.

Barry, as an ex-serviceman, who had associated with loyalists, was not at first trusted by many IRA officers.

Was it the case, then, that in 1920 he still hoped to forge a career in Imperial Service in either Ireland or India?

Perhaps, but there is another factor; Barry may have wanted to join the Volunteers throughout 1920 but been kept at arm’s length by the IRA themselves. Many senior IRA figures in West Cork did not trust him on account of his British Army service and postwar membership of the veterans’ association.

Barry himself admitted as much to the pension board in 1940.

‘They [the IRA officers] were naturally very doubtful about [ex British Army] fellows especially where arms were concerned. You might recall there were several occasions where fellows came home [from the War] and made contact and they were on British intelligence.’[14]

Ted O’Sullivan, who vetted Barry and eventually approved his application to join the IRA in 1920, but who seems to have bitterly disliked him, later implied to Ernie O’Malley that Barry was not only involved with ex-Servicemen, but also with militant loyalists in Bandon.

‘Tom Barry was in touch with the Anti-Sinn Fein Society in Bandon when he came home from the British Army. This society consisted of loyalists and the Essex Regiment… Sean Buckley stated that Barry joined the Irish Volunteers in 1919, but this was wrong’.[15]

Sean Buckley himself points to the arrest of Tom Hales in July 1920 and his replacement as Brigade commander by Charlie Hurley as the decisive moment: ‘ Charlie Hurley was a different man from Hales. Hales maybe felt that an ex-serviceman was not so much to be trusted’. [16]

Hurley is depicted as being a close friend and comrade of Barry’s in ‘Guerilla Days’; ‘a great patriot and lion-hearted soldier’.[17] However, we will never have Hurley’s version, as he was killed by British forces in March 1921, just before the Crossbarry ambush.

It seems that in August 1920, the Brigade, preparing to escalate their campaign, from assassinations and sniping to mobile guerrilla warfare, realised that they needed a man with military training who could train their Volunteers. Sean Buckley recommended Tom Barry and though, according to Ted O’Sullivan ‘the majority of the members of the staff were not enthusiastic about the selection’, Barry was taken on, initially as a training officer.[18]

Peter Hart suggests that support from Barry’s republican cousins might have played a part in his eventual acceptance by the IRA.[19] But Barry himself stated that family was a handicap; ‘if I had a brother or a cousin in the Volunteers [they might have vouched for him]… but my cousins were all in different ways throughout the period. [20]

The Tipping point

But there is a final factor. That Barry may have been given the final push to be a guerrilla by the actions of British forces in Cork. In his pension application he stated that the troops in Bandon were ‘beating the people with trench tool handles’ and that he asked a local IRA company for loan of a revolver to take them on in early 1920. He himself had apparently ‘taken a hiding’ after being suspected of passing information to the IRA in late 1919.[21]

It could be that the aggressive actions of the British garrison in Cork, including to war veterans, finally pushed Barry into joining the IRA.

His final act for the ex-Servicemen’s association was in July 1920, to act as part of a guard of honour at the funeral of their member, John Bourke, a former Munster Fusilier, who was bayoneted to death by British troops in a riot between them and some local ex-servicemen in Cork city on July 18.[22]

According to Liam Deasy, once taken on by the IRA, Barry, ‘threw himself into the work with an enthusiasm and dynamism that was astonishing’.[23]

In October 1920 he first saw action against Crown forces at the Tooreen ambush, at which three soldiers were killed, on October 22, after which he was given the command of the Brigade’s nascent flying column. Kilmichael, on November 28, 1920 was his first independent action as an IRA commander.

A man with something to prove?

It has been suggested that his late acceptance by the IRA meant that he had something to prove to them, which informed his subsequent fierce commitment to the guerrilla war.

It might also be that the ruthlessness that Barry displayed at Kilmichael and subsequently – in his pension application he listed off actions at ‘Drimoleauge, Crossbarry, Burgatia House, Rosscarbery and other small attacks on the police, assassinations … which killed more English soldiers, Auxiliaries, Black and Tans and RIC than any of these led by any other six senior officers in all Ireland’ – was the result of a feeling of betrayal that Barry had towards the British Army and Government after the Great War.

‘My column… killed more English soldiers, Auxiliaries, Black and Tans and RIC than any of these led by any other six senior officers in all Ireland’. Tom Barry, 1940.

One particularly poignant reversal of fortunes was Barry’s column’s abduction of the Earl of Bandon, as a hostage against British execution of IRA prisoners, in June 1921 and their destruction of his family seat, Castle Bernard. Lord Bandon, James Francis Bernard, a committed unionist, had been the head of the Bandon branch of the ex servicemen’s association, of which Barry had once been secretary in 1919-20. Not surprisingly, Barry does not mention this twist of fate in discussing the incident in his memoir.[24]

Some of the other ex-servicemen of Bandon as Sean Buckley noted, were ‘on the wrong side and became [Black and] Tans’.[25]

Tom Barry was 22 years old in 1920. Soldiering was the only occupation he had ever known. Across Europe many war veterans who could not settle into civilian life graduated to paramilitary formations of widely divergent political leanings, from Red Guards, to the German Freikorps to Mussolini’s squadristi , to various nationalist groups across the new states of eastern Europe and indeed to the Black and Tans and Auxiliaries in Ireland.

Barry’s experience in 1919-1920, probably tells us something of the choices faced by young people and war veterans in particular in the Ireland of 1920, amid an escalating political conflict, beginning to turn into guerrilla war.

But we must also be open to the possibility that Barry’s recruitment to the IRA was largely down to chance – his failure to secure a career in the civil service, a ‘hiding’ at the hands of British troops with whom he had been drinking and a personal friendship with Sean Buckley the Third Brigade’s Intelligence officer.

Such are the fortunes of war and revolution.

See also, Tom Barry and the Civil War

If you enjoy the Irish Story and wish to support our work, please considering contributing at our Patreon page here.

References

[1] Tom Barry, Guerilla Days in Ireland (1997) p.2 (Note: ‘guerrilla’ is usually spelt with two ‘r’s, but in Barry’s memoir, first published in 1949, it has one ‘r’.

[2] Tom Barry Military Service Pension Application (MSPC) 34REF 57456. Online here. (Barry’s pension is unusually long. This letter is on page 69 of the 245 page file)

[3] Barry MSPC file. This, like much of what Barry says, is hyperbole. Crown forces lost 27 men killed at Kilmichael and Crossbarry combined, out of about 800 police and military fatalities in Ireland from 1919-21.

[4] History, Ireland, Guerrilla Days in Iraq, by Mark McLaughlin.

[5] Peter Hart, The IRA and its Enemies, (1998) p.31, Meda Ryan, Tom Barry, IRA Freedom Fighter (2003), p.21

[6] Gerry White, From Gunner to Guerrilla, Tom Barry’s Road to Rebellion, Irish Times June 3 2020. He collected his British Army pension from August 1919 until June 1923, that is throughout his time as an IRA commander.

[7] White, From Gunner to Guerrilla

[8] Ibid.

[9] Barry MSPC file

[10] Ibid.

[11] White, From Gunner to Guerrilla

[12] Barry MSCP File

[13] Barry MSCP file

[14] Barry MSPC

[15] Andy Bielenberg, Padraig O Ruairc, John Borgonovo ed’s. The Men Will Talk to Me, West Cork Interviews by Ernie O’Malley (2015), p.159-160. O’Sullivan and some other Volunteers, including Ernie O’Malley and Liam Deasy, seem to have held a strong antipathy towards Barry by the 1940s. This seems to have been, not so much for his service in the British Army in WWI, as for his boastful and domineering personality and tendency to exaggerate and twist the facts in his recollections of the period. These anti-Treaty veterans of the Civil War also seemed to hold against Barry the fact that he fell out badly with the IRA leadership in July 1923 and resigned from the IRA Executive. The Pensions Board of 1940, dominated by former IRA Fianna Fail members probably also looked dimly on Barry’s time as IRA Chief of Staff in the 1930s, when he was convicted twice before Military Tribunals for arms possession and membership of an illegal organisation. He was eventually, however, after a marathon application process, awarded a full IRA pension from 1919 to 1923.

[16] Barry MSCP.

[17] Barry, Guerilla Days, p.94

[18] Ted O’Sullivan, BMH WS1478 (1956)

[19] Hart, IRA and its Enemies, p.32

[20] Barry MSPC

[21] Barry MSPC

[22] White, From Gunner to Guerrilla

[23] Liam Deasy, Towards Ireland Free, the West Cork Brigade in the War of Independence, (1973), p.141

[24] Barry, Guerilla Days, p.216-217

[25] Barry MSPC