From the Shipyards to the Poitín Still – Social Class and the IRA’s 3rd Northern Division

By Kieran Glennon

In a survey of the social structure of the IRA across Ireland during the revolutionary period, Peter Hart declared that “’The boys’ were farmers’ or shopkeepers’ sons rather than owners; apprentices or journeymen rather than tradesmen or masters; junior clerks and assistant teachers. Property, money and security, like marriage, lay in the future.”[1] To what extent was this true of the IRA’s 3rd Northern Division?

This article will investigate.

The Military Service Pensions Collection

Previous research on the IRA’s 3rd Northern Division has mainly focussed on what they did in the period 1920-22 and how many men served in the unit.[2] However, the files of the Military Service Pensions Collection (MSPC) provide additional and valuable insights into who they were and where they came from.

So far, the Military Archives have released files relating to 157 former members of the IRA, Cumann na mBan and Na Fianna from Belfast, Antrim and East Down, the three constituent Brigades of the 3rd Northern. Depending on the nature of the application, the files provide varying levels of detail on the occupations of those members and can be broken down into three groups:

From the Military Service Pensions Collection, we can piece together the social profile of IRA and Cumman na mBan activists in the 1920s, in this case for Belfast and the surrounding area.

- Application forms for dependent’s allowances or for wound/disability compensation involved explicit questions relating to the member’s occupation and earnings, as these were central to that process

- People providing references for applicants under the 1924 Military Service Pensions Act, which was limited to former members of the National Army, had to complete a form that asked, “What was his occupation prior to and subsequent to this period and to what extent was his living interfered with by his work as a Volunteer?”

- For applications under the 1934 Act, which was widened to include former members of Cumann na mBan and also IRA members who opposed the Treaty, the form did not ask about occupation but instead focussed exclusively on “military operations or engagements or service.”

So, there was a diminishing hierarchy of interest on the part of the authorities in who the applicant was and increasingly exclusive levels of focus on incidents of combat in which they had participated. This created particular obstacles for members of Cumann na mBan: “As no legislative definition of active service was provided, different assessors used different criteria at different times. Both the legislation and the subsequent assessors’ interpretations valued the role of women considerably lower than that of men…”[3]

In effect, the women of Cumann na mBan were treated as second-class revolutionaries: “A strict demarcation between the less-regarded work of Cumann na mBan and that of providing military support for the IRA informed the attitude of pension assessors.”[4]

However, the assessors also interviewed the applicants and the transcripts of these interviews often provide information relating to their employment. In order to present as broad a picture as possible of the wider republican movement in the 3rd Northern area, Cumann na mBan and Fianna applicants are included here. Antrim and East Down are included to avoid a Belfast urban bias, although there were far fewer applications from those areas.

Information from other sources has also been included to provide a final sample of 201 people from the Divisional area.[5] This compares with a sample of 138 for the whole of Ulster used by Peter Hart in his analysis.[6]

Social classes

While many of the IRA members ended up having to go on the run and/or took up full-time roles within the organisation, it is their occupation prior to that which is used to classify them. For the purposes of this analysis, a number of social classes have been used, which are broadly similar to those used by the Central Statistics Office, with a couple of additions:

- Professional

- Managerial

- Non-manual

- Skilled manual

- Semi-skilled manual

- Unskilled manual

- Not employed

- Farming

- Not known[7]

In general terms, the middle class would comprise 1 and 2 taken together, while the working class would include 3, 4, 5 and 6.

Before moving to consider the makeup of the republican movement in the 3rd Northern area, it is necessary to understand the wider context, as shown in the 1911 Census:

“In 1911 catholic men were over-represented, in descending order, in general labour, flax spinning, factory labour and boot and shoe manufacturing. They were under-represented, in descending order, among shipwrights and carpenters, shipbuilders, boilermakers, engine and machine makers, house carpenters, plumbers, fitters and turners, drapers/mercers and printers. Catholic women were similarly disadvantaged.”[8]

On this basis, we should then expect the unskilled and semi-skilled manual workers to account for high percentages of the current sample. Similarly, we should expect the middle class, the professional and managerial groups, to be relatively small: “The catholic middle class was not numerically large. In 1911 there were only 17 catholic merchants out of 132 enumerated, and just over 1,000 male and female clerks out of well over 7,000 in the city.”[9]

Who were they?

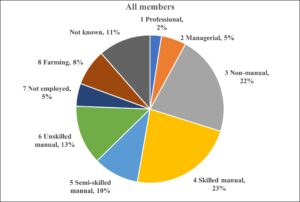

The first thing that can be said, using the definitions above, is that the republican movement in the 3rd Northern area was predominantly working class – its four component groups account for just over two-thirds, or 68%, of all members. This percentage increases to almost three-quarters, or 73%, of IRA members only.

The middle class made up just 7% of total members, so it was a small component, in line with expectations. There were only five professionals, of whom three were doctors who acted as Medical Officers at either Divisional or Brigade staff level. Eleven were managerial and of these, six were owners of small businesses, such as Ned Trodden who owned a hairdressers on the Falls Road.[10]

The republican movement in the 3rd Northern area was predominantly working class, though less so in officer ranks.

Forty-four were non-manual workers, involved in a wide range of occupations such as teacher, clerk, shop assistant and barman. The largest group were the forty-six skilled manual workers – engineers, electricians, car mechanics and so on. The sizes of these two groups do not match expectations, as each is considerably bigger than might have been anticipated.

However, the two groups that we supposed would be over-represented, the semi-skilled and unskilled manual workers, were actually relatively small – even added together, they still only matched the skilled manual group in terms of size.

Of the twenty semi-skilled manual workers, exactly half were apprentices and another six were drivers of taxis or other motors.

Thirteen of the twenty-six unskilled manual workers were labourers. This unskilled manual group also includes ex-servicemen for whom no other post-war occupation can be found – for example, IRA member Joseph Giles, one of the first people to be killed in the political violence which erupted in Belfast in July 1920, was described as being “only recently demobilised.”[11] Fourteen, or 8%, of the total of 167 IRA members included in the sample, were noted as being ex-servicemen.

Farmers and ex-servicemen were underrepresented in the Third Northern Division.

Of the ten members “not employed”, five were unemployed and four were students; Rose Black was the only member of Cumann na mBan described as being engaged in “house duties.”[12]

While it might be expected that most members from the “country” Brigades in Antrim and East Down were engaged in farming, this was not so. Only sixteen of the total sample were classed under this heading – ignoring the Belfast Brigade for obvious reasons, the farming group still accounted for only 30% of the combined membership from the Antrim and East Down Brigades.

In fact, in the Antrim Brigade, there were three times as many in non-farming occupations as were engaged in farming. This may reflect the geography of the county, as nationalists were concentrated in the Glens of Antrim where the land was poorer: it is perhaps indicative that of the nine glens, the name Glenariff is an anglicisation of Gleann Áireamh, “the arable glen” or “glen of the ploughman”, but the names of the other eight have no such agricultural reference.[13]

Two IRA members in the sample almost defy classification.

In addition to the fourteen ex-servicemen, there was a serving British soldier in the IRA’s Belfast Brigade – Sergeant James Tully, who was a clerk at Victoria Barracks on the Antrim Road:

“Sometime in 1919 he intended to resign but remained in his position at our request. In addition to intelligence from military quarters, his uniform made him a welcome guest in the different RIC Barracks and he often supplied us with information re. RIC. In Feb 1923 documents containing information which could only have been supplied by Tully were captured by the RUC and as result he was compelled to cross the border.”[14]

On account of his military duties, Tully is classed as “non-manual” in the sample.

At the completely opposite end of the spectrum of legality was Mick McIlhaton, listed on the nominal roll of members of the Ballycastle company in the Antrim Brigade’s 1st Battalion. He was arrested and interned on the Argenta: “He came up, I guess, Mick McIlhaton said ‘I was a shepherd or I was a poitín maker?’ Says he was both!”[15] Despite this obvious entrepreneurial flair, McIlhaton is classed as “farming” in the sample.

Full details of the sample and their occupations can be found here.

Officers

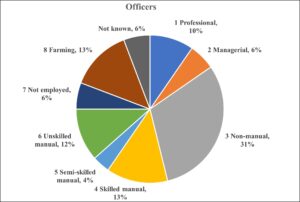

Compared to the total sample, the composition of the officer cadre was noticeably different.

Fifty-two individuals can be identified as having been staff officers, at either Battalion, Brigade or Divisional level for one of the three republican organisations – forty-nine IRA, two Cumann na mBan and one Fianna.[16]

While the four working class groups still accounted for the majority (60%) of all officers, there was a marked shift in the balance between those four groups, with a distinct swing away from the skilled and semi-skilled manual groups towards the non-manual group, which became the largest group among the officers.

Taken together, the professional, managerial and non-manual groups accounted for almost half, or 47%, of all officers.

But as the semi- and unskilled manual workers still provided as many officers as the professionals and managers, it is most accurate to say that the officers of the republican movement were more white-collar – as opposed to more middle class – than the wider membership.

Affected by the pogrom

The events known as the Belfast pogrom began on 21st July 1920 with the driving out by loyalist mobs of thousands of workers from the shipyards, including both Catholics and so-called “rotten Prods”, socialists and trade unionists who were also viewed as being “disloyal.” The expulsions spread the following day to other notable Belfast employers, especially those in the engineering industry.

As shipbuilding was a significant industry and source of employment in Belfast, it is not surprising to see that several IRA members worked in the shipyards. Ten members, or 9% of the Belfast Brigade in the sample were employed in either Harland & Wolff or the “wee yard”, Workman Clark. In addition, a member of 3rd Northern’s Divisional staff, Quartermaster Frank McArdle, had been employed in the drawing office of Harland & Wolff and was well-regarded by no less a luminary than the owner, Lord Pirrie.[17]

Three more IRA members worked in Combe Barbour, an engineering firm that saw expulsions on 22nd July 1920, and Bernard McAvoy was an apprentice fitter in Mackie’s, another site of workplace expulsions.[18]

Some Belfast IRA members (including some Protestant members) lost their jobs in the shipyard expulsions of July 1920

Some Belfast IRA members were put out of their jobs: James McDermott, who went on to become O/C 1st Battalion, was an apprentice smith in Harland & Wolff until he was “expelled at [the] pogrom”; Patrick McWilliams, an apprentice machinist in the same firm, “lost his job in the shipyard in July, 1920…” Tom McNally, who later became Divisional Quartermaster, was a railway clerk until he was “hunted from my work by one of these mobs.”[19]

Others, while not physically driven out themselves, simply deemed it more prudent to no longer show up for work: “Frank McArdle himself had to be kept in close cover to protect him from the mob until late evening and then smuggled out of the premises. It was, I think, his final departure from the shipyards.”[20]

All of these men had been in the IRA prior to July 1920, so their membership pre-dated the workplace expulsions. But the case of James McLaughlin is more intriguing: also employed in the shipyards, he lived in Foundry St, Ballymacarrett in east Belfast, where rioting broke out at teatime on the first day of the expulsions; although he doesn’t mention being driven from his work, his file states that he joined the IRA in July 1920 – what were his motives for joining…?[21]

Charles Stewart was an apprentice machinist in Harland & Wolff who joined the IRA in March 1921; however, he was an exceptional recruit, as “…being a Presbyterian I was not expelled at time of pogrom but owing to activities with IRA was expelled later.”[22]

But it was the women of Cumann na mBan who were more likely to explicitly highlight the impact of this period on their livelihoods.

Of the twenty-six members in the sample, five said they lost their jobs as a result of their republican involvement, beginning with Elizabeth Corr who was dismissed from her position as a librarian with Belfast Corporation because of her role in the 1916 Easter Rising. Mary Hackett lost her job when “ammunition was found in my workshop”. Jane O’Neill had been a typist in a solicitor’s office in Ballymena but lost her position and “believes it was as a result of her activities.”

Mary Russell worked in Spence & Johnson, a Belfast motor company attacked by the IRA: “I was in business until the day I was arrested & the firm I was in, the workers refused to work with me, the result was I could not get in any place.”[23]

Nellie O’Boyle provides an addition to the growing body of evidence linking Belfast republicans to the anti-Treaty side in the Civil War: having been involved in Cumann na mBan since 1914, she ferried arms to a Belfast IRA column operating in Louth; arrested by Free State authorities in 1923, “she was unable to resume her old employment in a loyalist firm by reason of her political activities, arrest, etc and the subsequent depression in other firms rendered it impossible to obtain other employment.”[24]

The women of Cumann na mBan who were more likely to explicitly highlight the impact of this period on their livelihoods, many being sacked as result of their republican activities

One of the possible reasons why Cumann na mBan applicants were more likely to highlight their loss of livelihood may be that while some women had received the right to vote in 1918, by the time of the pogrom, these Cumann na mBan women were still excluded from the franchise on the grounds of age and/or lack of property qualifications. They may therefore have felt the loss of whatever scraps of economic agency they had achieved more keenly than their IRA counterparts.

Apart from the women who were sacked, sisters Alice and Annie McKeever ran a confectionery and tobacco shop at 74 Cromac St in Belfast, but by the mid-1930s “As a result of our national sympathies and work, our business was boycotted and as a result my sister and myself are entirely without means.”[25] Emily Valentine also lost everything: in August 1920, her parents’ home was burnt out by a hostile mob and the family had to move to Dublin.[26]

Summary and conclusions

In 1920, although a post-war recession was looming and thousands of recently demobilised ex-servicemen were adding to the existing competition for jobs, Belfast was still the leading industrial city in Ireland, with two large shipyards and many other significant companies in the engineering, linen, tobacco and rope-making industries.

The working-class population of the city was therefore much more sizeable than was the case in other cities and towns around Ireland at the time. However, discriminatory employment practices meant that within the Belfast working class, Catholics were disproportionately over-represented at the lower rungs while being under-represented among the skilled manual layer.

We would therefore anticipate that membership of republican organisations in the city would be skewed towards the unskilled and semi-skilled manual working class. Adding the membership from the two “country” Brigades of 3rd Northern Division could be expected to significantly increase the proportion engaged in farming.

The Belfast IRA of the early 1920s was disproportionately composed of the skilled working class, whereas Catholics in general were underrepresented in this class in the city.

Analysis of the sample of 201 members shows that neither was the case.

Over two-thirds, or 68%, of those in the sample were working class. But the single largest group was the very one in which Catholics were under-represented generally – skilled manual workers, who accounted for 23% of the total; the next-biggest group was drawn from the non-manual working class, another section of the workforce among which Catholics were generally under-represented.

Outside Belfast, farmers and their families were only a minority of republican activists – in both Antrim and East Down, they were outnumbered by those in non-farming occupations.

The officers of the republican movement were also substantially working class, though at a slightly lower percentage than those they led, 60% compared to 68%. However, this leadership had a distinctively different composition, with a pronounced white-collar, though not middle class, slant. While skilled manual workers were the largest group among the total membership, non-manual workers were the biggest among the officers.

With the shipyards being the biggest employers in Belfast, it was perhaps only natural that several IRA members were also employed there. What is surprising is that only two of those made any reference to have been driven from those jobs at the outset of the pogrom; another, working as a railway clerk, was also expelled from his position. Other Belfast IRA members may have been ejected from their jobs, but if they were, they didn’t say so. Given that July 1920 was the defining moment that marked the start of the pogrom, with a wave of workplace expulsions, it is perhaps extraordinary that so few of the Belfast IRA, over 90% of whom were working, claimed to have been victims of that outbreak.

IRA and Fianna members faced a particular risk that of being killed or wounded, although securing a dependent’s allowance or disability pension could at least soften the subsequent financial blow. While engaged in attacking an RIC Barracks in April 1920, Hugh MacGlennon was accidentally doused in burning petrol and suffered horrific injuries to his face and hands; for years afterwards, the Free State authorities not alone paid him a disability pension but also provided plastic surgery for him. The application for an IRA wound pension by Charles Stewart, the Presbyterian one-time apprentice in Harland & Wolff, was supported by letters written by a doctor from the Shankill Road in Belfast – probably one of the more unusual requests that particular medic had to deal with.[27]

Members of all three republican organisations also lived with the constant threat of being punished by either the authorities or their employers for their activities.

Of the total 3rd Northern IRA membership, 145 were interned. But for some of these, there could later be redemption, at least in terms of their livelihood: Hugh Corvin, Quartermaster of the “Executive” or anti-Treaty 3rd Northern after the 1922 split, was interned on the Argenta but by the mid-1930s, he had his own accountant’s firm in Belfast.[28] For those who avoided internment, there were other options: forty-three, or a quarter, of the IRA members in the sample joined the National Army in the south during the Civil War.

Several of the Cumann na mBan members in the sample were also arrested and/or interned. But for the women of this organisation, the impact on their employment prospects seemed to be more lasting and more acutely felt.

By the time internees started being released and the Civil War came to an end in the south, Belfast’s industrial heyday was ebbing away. The recession had hit hard: “By June 1923 there were 65,507 jobless and 43,575 on short-time out of the north’s 260,000 insured workers.”[29] Discrimination in employment against Catholics had already been present before the Great War, now it was reinforced by discrimination in housing and voting as unionism strengthened the structures of a sectarian state.

On 30th October 1924, the remains of Joe McKelvey, the first O/C of the 3rd Northern Division, executed by the Provisional Government on 8th December 1922, were buried in Belfast’s Milltown Cemetery. The symbolism of the funeral need hardly be emphasised – as well as McKelvey, the 3rd Northern was also finally buried. The funeral acted as the catalyst for republicans to begin trying to rebuild the IRA in Belfast.[30] But they were doing so in a vastly different world.

References

[1] Peter Hart, The IRA at War 1916-1923, (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2003), p121-122.

[2] Jim McDermott, Northern Divisions – The Old IRA and the Belfast Pogroms 1920–22 (Beyond The Pale Publications, Belfast, 2001); Robert Lynch, The Northern IRA and the Early Years of Partition 1920–1922 (Irish Academic Press, Dublin, 2006).

[3] Marie Coleman, Compensation Claims and Women’s Experience of Violence in Linda Connolly (ed.), Women and the Irish Revolution (Irish Academic Press, Newbridge, 2020), p130.

[4] Margaret Ward, Gendered Memories and Belfast Cumann na mBan, 1917-1922 in Connolly (ed.), Women and the Irish Revolution, p59.

[5] Primarily: McDermott, Northern Divisions; Denise Kleinrichert, Republican Internment and the Prison Ship Argenta 1922 (Irish Academic Press, Dublin, 2001); Thomas Gunn memoir, ‘Reorganisation in Antrim’, Michael Collins Papers, Military Archives (MA), MA/CP/062/001; witness statements provided to the Bureau of Military History (BMH). Newspaper reports were a disappointingly scant source of occupational information, as reporting conventions at the time seemed to focus almost entirely on people’s name, age and address; this was true even of high-profile trials of multiple IRA defendants e.g., the “Arthur Hunt affair” of October 1921 – see Belfast News Letter, 8th, 9th, 13th, 23rd & 29th November 1921.

The present sample of 201 comprises 167 IRA (10 3rd Northern Divisional staff, 112 from the Belfast Brigade, 27 from Antrim and 18 from East Down), 26 Cumann na mBan (18 from Belfast, 8 from Antrim) and 8 Fianna. Previous research by this author has established a total of 2,403 members of the IRA’s 3rd Northern Division. Membership records for the other republican organisations are incomplete – for Cumann na mBan, there are no nominal rolls at all for either Belfast or East Down and only a roll for one of the four battalions in Antrim (4th Battalion – 22 members, see MSPC, MA, CMB-62); for Na Fianna, there is a nominal roll for just one battalion in Belfast (1st Battalion – 115 members on 11th July 1921, some of whom may have subsequently “graduated” to the IRA, see MSPC, MA, FE-34); there are no Fianna records for either Antrim or East Down. The sample thus represents 7% of IRA members and an unknown percentage of Cumann na mBan and Fianna members.

[6] Hart, The IRA at War 1916-1923, p137.

[7] Examples of the different groups are as follows:

- Professional: doctor, dentist, lawyer, etc

- Managerial: higher-ranking “white-collar” e.g., school principal; also included here are people who would otherwise be classed as “skilled” or “semi-skilled” but who owned their own business e.g., William Lynn was a car mechanic but owned his own garage in Ballycastle, Co. Antrim – see William Lynn, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF 07497

- Non-manual: teacher, accountant, clerk, shop assistant, barman, etc. Owing to the general (in some cases, extreme) youth of the activists, they can safely be assumed to have been at non-managerial grades e.g., accountant Seamus Woods, O/C of 3rd Northern Division in 1922, was then aged only 22 – see MSPC, MA, 24D39; his predecessor, Joe McKelvey, a trainee accountant, was aged only 24 when executed in Mountjoy Prison in December 1922 – see Jim McVeigh, Goodbye, Dearest Heart (National Graves, Belfast, 2017).

- Skilled manual: electrician, engineer, etc e.g., John Lynn was also a car mechanic, working in his brother William’s garage – see John Lynn, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF 22241

- Semi-skilled manual: taxi driver, apprentice, etc

- Unskilled manual: labourer, carter, etc

- Not employed: women working in the home, student, unemployed

- Farming: farmers and their families; farm labourers are counted as unskilled manual

- Not known: no occupational information could be found for 23 (11%) of the MSPC applicants.

[8] Austen Morgan, Labour and Partition, The Belfast Working Class 1905-23 (Pluto Press, London, 1991), p10.

[9] Ibid, p14. Morgan counts clerks as middle class but in the current analysis, they are counted as (non-manual) working class – although they may well have had different perspectives on potential social mobility to their manual working class counterparts.

[10] Edward Trodden, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, 1D153. Winifred Carney is also included in this group – while it may seem contradictory to describe a trade union official as “managerial”, this was felt to be the best fit for her leadership role as Secretary for the Belfast branch of the Irish Transport & General Workers’ Union – see Winifred Carney, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF 56077.

[11] Belfast News Letter, 23rd July 1920.

[12] Rose Black, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF 22470.

[13] https://antrimcoastandglensaonb.ccght.org/cultural-heritage/

[14] James Tully, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, 24SP11058.

[15] Nominal Rolls, 1st Battalion, 2nd Brigade, 3rd Northern Division, MSPC, MA, MSPC/RO/408; Kleinrichert, Republican Internment, p243.

[16] Rose Black was attached to the IRA Belfast Brigade staff and instructed not to attend Cumann na mBan meetings – Rose Black, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF 22470. Similarly, Alice Flynn was also attached to the IRA Belfast Brigade staff and in her interview with the pension board assessors, she stated that she wasn’t in Cumann na mBan (although her application form says she was) – Alice Flynn, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF 57942. Both of these women are therefore counted as being officers.

[17] McDermott, Northern Divisions, p38.

[18] Bernard McAvoy, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, 24SP12878.

[19] James McDermott, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, 24SP9856; Patrick McWilliams, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF 51215; Tom McNally statement, BMH, MA, WS 410.

[20] J. Anthony Gaughan (ed.), Memoirs of Senator Joseph Connolly, a Founder of Modern Ireland (Irish Academic Press, Dublin, 1996), p176.

[21] Patrick McLaughlin, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, 24SP7961.

[22] Charles Stewart, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, DP7030.

[23] Elizabeth Corr, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF 10854; Mary Hackett, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF 23258; Jane O’Neill, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF 34428; Mary Russell, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF 24769.

[24] Nellie Neeson (née O’Boyle), Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF 11037.

[25] Alice McKeever, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF 51358.

[26] Emily Valentine, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF 56551.

[27] Hugh MacGlennon, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, 1P566; Charles Stewart, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, DP7030.

[28] Although Corvin’s MSPC file (if any exists) has not yet been released, he provided references for applicants under the 1934 Act on the headed notepaper of Corvin & Thornbury, Auditors & Accountants, of 4 College Square North in Belfast – see for example: Terence Lee, Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF 06056 and Nellie Neeson (née O’Boyle), Pensions & Awards files, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF 11037.

[29] McDermott, Northern Divisions, p38.

[30] John Ó Néill, Belfast Battalion – A History of the Belfast IRA, 1922-1969 (Litter Press, Wexford, 2018), p21.