Ireland and the Anglo-Zulu War, 1879

By John Dorney

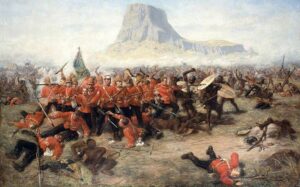

On January 22, 1879, under a mountain named Isandlwana, a Zulu force, some 20,000 strong attacked a British military encampment containing about 1,700 men; British regulars, colonial volunteers and native levies, part of a column that had invaded Zululand only twelve days earlier.

The British commander Lord Chelmsford, had committed a series of blunders. The camp had not been fortified, no one was clear who was in command of it and the larger part of the British column, including Chelmsford himself, was out searching for the Zulus in the hills some twelve miles distant from the camp, at the time of the attack.

By the afternoon of the 22nd, all but a few hundred of the camp’s garrison were dead, shot, stabbed and in most cases ritually disembowelled too, lying among the wreckage of the encampment. There was no shortage of Irishmen among the British dead. Both of the two commanders of the camp had Irish links. One was Colonel Anthony Durnford, who was born in County Leitrim. The other, Lieutenant Colonel Henry Pulliene’s wife Fanny (nee Bell) was from Fermoy in County Cork.

Many Irish soldiers died in the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879 but not everyone in Ireland mourned their deaths or accepted the legitimacy of the war itself.

Nevill Coghill, one of two lieutenants who were posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross for attempting, unsuccessfully, to save the regimental colours, was born in Drumcondra in Dublin. He was one of hundreds of men caught attempting to flee the stricken camp on horseback and killed by the pursuing Zulus.

Other officers killed that day included Lieutenant George Hodson of Bray, County Wicklow, Major Stuart Smith of the Royal Artillery, from Ballintemple County Cavan and Francis Hartwell McDowell, of Dublin, son of a professor of medicine at Trinity College Dublin. Indeed, a list of 114 British officers killed in action in the campaign lists thirteen born in Ireland and doubtless a search of the rank and file casualties would find far more. [1]

But not everyone in Ireland mourned the British dead of Isandlwana. The nationalist newspaper The Nation commented ‘Isandula [sic] hath warmed each true man’s heart, hurrah for the Zulu king, hurrah for his warriors brave and soon may their shouts of victory ring’.

Michael Davitt, the Land League organiser, told a rally at Gurteen County Sligo that, there was ‘great similarity between the Irish pike and Zulu assegai [spear] and English soldiers who went to civilise the Zulus at the point of the bayonet found that the savage African knew how to handle an assegai almost as well as our ancestors knew how to handle a pike in [17]’98’. He was indicted for treason for the speech.

At another Land League meeting in County Galway, where the crowd cheered for the Zulu King, Cetshwayo , the speaker, Malachi O’Sullivan told them, ‘you do well to cheer for the Zulus. After 700 years you know what it is to live under English rule and you know well what the Zulus will suffer if they are brought under that rule. [2]

A complex relationship with Empire

The Anglo-Zulu War of 1879 was one of two wars waged by the British Empire in that year – the other was in Afghanistan – and in terms of length, casualties and strategic importance (Afghanistan being part of the competition between the British and Russian empires in central Asia), it was the latter conflict that was of more significance at the time.

Yet the Anglo-Zulu conflict, the clash between an industrialised European empire, fielding the latest breach-loading rifles, artillery and early machine guns, and an African kingdom, whose warriors were principally armed with spears, still fascinates. In part this is due to its depiction in films such as the 1963 film Zulu, but also perhaps for the stark contrast in cultures and military technology. Especially since the Zulus were, for a time, surprisingly successful against the British invaders.

Perhaps also, the unequal struggle represents today the cruelty of the remorseless advance of European colonisers over the African continent. The apparently stark racial aspect of the war –though in fact large numbers of Africans fought, some willing, some forced, for the British – also lends it an extra frisson in the popular mind.

For this reason, the war provides an interesting window into Ireland’s tortured and many sided relationship with the British Empire. Was Ireland a full and enthusiastic contributor to Empire, as some claim? Or the oldest and longest subjugated colony in that empire, as Michael Davitt and his comrades maintained in 1879?

Zulus, Boers and British

Before launching into Ireland’s relationship with the war, it is necessary first to explain the context of nineteenth century South Africa. The Zulu and British empires both came to prominence in South Africa in the early nineteenth century.

The British first arrived there in 1795, taking over the Dutch colony at Cape Town in order to secure the sea route to India and formally annexed it 1806.

They inherited there a Dutch-speaking European group, known at the time as ‘Boers’ (literally ‘farmers’) and later as ‘Afrikaners’, and a ‘coloured’ population, descended from Khoi people, that was largely pressed into the service of the Boers as agricultural labourers. Along the Cape frontier to the east, the British also inherited a series of frontier wars with the Xhosa people.

From the 1820s, significant numbers of settlers also began to arrive at the Cape from Britain itself, including from Ireland.

By the 1840s, the Zulu Kingdom British ruled Natal province and the Boer Transvaal Republic all lived uneasily alongside each other.

Some 1,000 km to the east of the Cape frontier, at around the same time as British immigrants were beginning to arrive in Cape Town, the Zulus, previously an insignificant clan, emerged, under the charismatic king Shaka, as the dominant force in the region. The Zulu state was a militarised kingdom, that grew out of a period of warfare and turmoil, known as the ‘Mfecane’ or ‘crushing’ , among the Nguni peoples of south eastern Africa.

Shaka’s kingdom did not start the warfare, which is thought to have been prompted by a period of drought and famine, leading to deadly competition over resources such as grassland for cattle, but it emerged as the ultimate victor. By the 1820s it was the preeminent kingdom in south eastern Africa.

The Zulu state was premised on the mobilisation of all available male manpower as soldiers, organised in age-based regiments known as amabutho (singular ibutho) that lived in military barracks known as amakhanda and were directly responsible to the king and his indunas or officers, rather than to their own clan chieftains. Warriors were not allowed to return home and set up their own homesteads until permitted to marry by the king, which could be as late as the warriors’ 30s or even 40s.

This was not, as the Victorians came to imagine, a means of channelling frustrated sexual energy into aggression, but rather a means of keeping a large standing army in being. While Zulu social mores did allow for sexual activity before marriage, once the warriors settled down to family life, they could only be called upon by the king for limited periods.

The upshot of the ibutho system was that throughout the period of the independent Zulu Kingdom, that is from 1817 until 1879, it possessed a large and well trained army, about 20-30,000 strong at all times. It was armed mainly with a short stabbing spear and cowhide shield, though these were, in later decades, augmented by rifles and muskets in large quantities which were mostly purchased from the Portuguese colony in modern Mozambique.[3]

By the 1840s, however, the Zulus had not one but two aggressive European settlements on their borders. The Boers, groups of whom trekked east to escape British rule and set up their own states in the 1830s, set up three independent republics, in the Orange Free State, Transvaal, and that area which they prised off the Zulu kingdom after a bloody series of battles, that they christened Natal.

The British followed them within a few short years, however, annexing Natal in 1843 and substantially settling it with British immigrants, including some Irish. One, for instance, was Jim Rorke, whose father and uncles had come from County Galway to the Cape in the 1820s and who in the 1840s gave his name to the ford over the Buffalo River; ‘Rorke’s Drift’, at which one of the most famous actions of the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879 would be fought. [4]

That said, the European population of both Natal and the Boer republics was dwarfed by the native Africans, who were systematically excluded from the Europeans’ political system and often stripped of the best arable and grazing lands.

Nevertheless, relations between the British, Zulu and Boer states remained reasonably peaceful from the 1840s until the late 1870s. In the 1860s, diamonds were discovered in the Transvaal and from the middle of the following decade, the British administration embarked on a strategy of ‘confederation’ by which all the disparate authorities (and their mineral resources), both European and African, in southern Africa, would be brought together under British control.

To this end, the British annexed the Transvaal Republic in 1877 and fought a number of small campaigns against the Xhosa and other African kingdoms in 1877-78. The overarching British strategy was to eliminate independent native armed forces and, equally important, to secure a supply of black African proletarian labour for the mines and the other hoped for industries of British South Africa.

As it was, most Africans preferred to live as they had always done; as subsistence farmers and cattle grazers, mostly outside of the cash economy and therefore with no need to work as wage labourers for the Europeans. The Zulu kingdom, with its manpower carefully organised along military lines and, at least in British minds, providing a focus for native resistance, was the most powerful remaining obstacle to the confederation policy by late 1878.

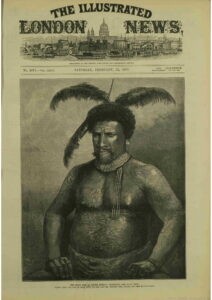

So, Theophilus Shepstone, Secretary for Native Affairs and sir Bartle Frere High Commissioner for Cape Province, manufactured a crisis that enabled them to go to war with the Zulus. In the press, both in Britain and South Africa, they portrayed, falsely, the Zulu kingdom as an imminent threat to Natal, when in fact, the king Cetshwayo desired only peaceful relations with the British and had even allowed the British to ‘crown’ him as king at a coronation ceremony in 1873.

In the 1860s, diamonds were discovered in South Africa after which the British resolved to subdue all the other political actors in the region.

Seizing on a border incident, in which the sons of a Zulu chieftain, Sihayo, abducted and killed several Zulu women, who had fled to Natal to escape from arranged marriages in Zululand, Frere issued an ultimatum in December 1878 to the Zulu King, Cetshwayo.

The terms included a demand to disband, within 30 days, the Zulu military system and accept a British governor as well as the handing over of several prominent Zulus – Sihayo’s sons and a chieftain involved in a border dispute with the Boers – to be tried by the courts in Natal and Transvaal. All of which the British knew that the Zulus could not accept. Despite Cetshwayo’s pleas for mediation, when the period of the ultimatum ran out, British forces invaded Zululand. [5]

This was done without the explicit authorisation of the London government and British Prime Minister, Disraeli. The government approved in theory of the ‘confederation’ policy, but with war also brewing in Afghanistan, did not want to allocate extra military resources to South Africa. It was hoped by Frere and Shepstone, the men on the ground, that the campaign would be over and the Zulus defeated before London could object.

The War of 1879

The British commander, Frederick Thesiger, Lord Chelmsford, proposed to invade Zululand in three columns, converging on king Cetshwayo’s seat at Ulundi.

However, he badly underestimated the military capabilities of the Zulus, who outnumbered his force substantially. Just twelve days after entering Zululand, about half of his centre column was annihilated in the camp at Isandlwana. The remainder had to limp back across the border into Natal. The disaster was only very partially alleviated by the achievement of a small garrison of about 150 British troops in holding the frontier post at Rorke’s Drift against a force of up to 4,000 Zulus.

To the south the second column advanced towards Eshowe and established a fort there but soon found itself besieged and immobilised.

The third column, to the north under Evelyn Wood, initially also suffered reverses. A supply party was ambushed and destroyed by the Zulus at Ntombe, with the deaths of 80 soldiers and auxiliaries, including one Captain David Barry Moriarty of Kilmallock County Limerick. A subsequent attempt by Wood to root out the local abaQulusi clan from their stronghold on Hlobane Mountain ended in a bloody failure for the British, with the loss of over 200 men.

The Zulu king Cetshwayo hoped that these successes could be a prelude to negotiations with the British, but in fact they sealed the fate of his kingdom.

Disraeli’s government was most dismayed by the series of humiliating setbacks in a war which they had not authorised. Nevertheless, Imperial prestige was now on the line, and so, after Isandlwana, they sent extensive Imperial reinforcements to South Africa, including up to 16,000 regular troops, more artillery, Gatling guns and cavalry.

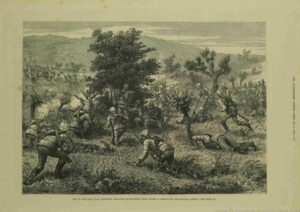

Unsurprisingly, the tide quickly turned against the Zulus. The main Zulu army suffered a costly defeat when it attacked Wood’s fortified camp at Kambula on March 29. Meanwhile, a chastened Chelmsford led a column to relieve the besieged force at Eshowe and his infantry, securely protected in a laager (wagon fort) inflicted heavy losses on the Zulus at Gingindlovu, before escorting the Eshowe garrison back into British territory.

Finally, Chelmsford regrouped and led a second invasion of Zululand, this time in overwhelming force. As they marched through the country, they systematically burned all the homesteads, villages and food supplies they could find. In July 1879, his forces routed the main Zulu army, at little cost to the British, at the battle of Ulundi. Ulundi, the Zulu capital, was burned.

This was the effective end of the war which had lasted just over six months and cost about 10,000 lives, about 80 per cent of them Zulu. [6]

The War of 1879 initially went badly for the British but within six months the Zulu state was shattered and dismembered.

Chelmsford had by this time been replaced as commander by Sir Garnet Wolesley on the orders of an impatient London government. Wolesely arrived too late for the climactic battle at Ulundi and to him was left merely capturing the fugitive king Cestshwayo and imposing a peace settlement on the Zulus.

Cetshwayo was duly run to ground and sent into exile, first in Cape Town and then in England. However, Frere’s aim of annexing Zululand was in the short term, reversed. Instead, the Zulu kingdom was partitioned between thirteen local chieftains, the army and monarchy abolished and a British ‘Resident’ appointed to oversee the territory.

Unsurprisingly perhaps, Zululand lurched into civil war in the following years, with rival chieftains fighting each other and partisans of the Royal house attempting to restore the monarchy. Such was the chaos in the kingdom that the British allowed Cetshwayo to return in 1882 to attempt to restore order, but his forces were defeated in battle with a rival faction in 1883.

In 1887, amid further internecine violence and with the Transvaal Boers having become involved in the fighting, the Zulu kingdom was finally forcibly annexed by the British Empire.

Dinzulu, Cestshwayo’s son, was imprisoned and exiled to St Helena as punishment for a short-lived uprising against British rule in 1888.

It was not until 1902 that Zululand was opened to European settlement, but after it was, much of the best land there was taken by white settlers and some of the country developed for coal mining and sugar cane farming. A final Zulu uprising, sparked by the imposition of poll tax, was bloodily put down by the Natal authorities in 1906. [7]

Irish involvement in the war: the rank and file

In 1879, roughly 20 per cent of the British Army was Irish born. One Irish unit, a battalion of the 88th Regiment of Foot, or Connaught Rangers[8], took part in the Zulu campaign but only marginally.

The 88th had been sent to the Cape in 1877 and fought against the Xhosa in Ninth Frontier War in 1878. Thereafter they were used as garrison troops in King William’s Town where, ‘the more genteel of the population were glad to see the wild Irishmen depart. They thought the troops’ behaviour was disorderly and a danger to the town’s citizens’. [9]

During the invasion of Zululand, they were employed building and garrisoning forts up the Zulu coast where they saw, ‘a good deal of hard work, but no fighting’. Out of 640 men in the battalion, five died of disease, but none due to enemy action. They were sent to India in October 1879. [10]

Outside of this however, a significant number of rank and file soldiers in other units were also Irish. For example, Dan Harvey identifies 32 out the 150 strong garrison at Rorke’s Drift (members of the 24th Regiment) as being either of Irish birth or descent. [11]

About one in five of the regular soldiers in the British Army in 1879 were Irish. One Irish regiment the 88th Foot, participated in the Zulu campaign.

No great political significance can be placed on the activities of ordinary Irish soldiers in British service, who served wherever they were sent.

Quite unlike the African levies raised by the British for the war of 1879; the Natal Native Contingent and Natal Native Horse, the Irish soldiers served on exactly the same terms as any other enlisted British soldier.

Nevertheless, it is interesting to see how the 88th in particular, who were mostly recruited from poor, largely still Irish speaking counties in the west of Ireland, were viewed as uncouth ‘wild Irish’ by colonial British society in South Africa.

Of greater importance, perhaps, for Ireland’s engagement with the British Empire, was the presence of Irishmen in senior positions in the British Army officer corps.

The officer corps

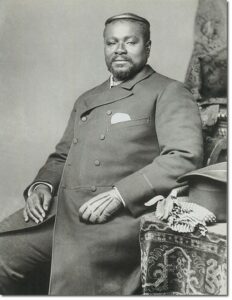

Many of these officers were from army families, who had settled in Ireland after their service. Sir Garnet Wolesley, for instance, who commanded the British military in South Africa in last phase of the war and imposed the partition of the Zulu kingdom, was born and raised in Dublin, son of an officer and of a grandson of another who had ‘squandered the family fortune in a crack cavalry regiment’.

Garnet Woleseley joined the Army at 18 and subsequently fought in wars from the Crimea to India, Canada (including against the attempted Fenian incursions), West Africa, Egypt and Sudan and finally rose to be commander in chief of the entire British military in 1895. [12]

While Wolesely lived in Ireland until he was 18, as Sean Gannon notes, he ‘maintained an ambivalence .. even an antipathy’ towards Ireland. ‘For Wolseley, Ireland was “this dirty Paddyland”, his native Dublin … “entirely a foreign town” where “I seem surprised to hear [the] people speak English”. Meanwhile, the Irish were … “an amusingly, provokingly, inconsequent people”’. [13]

Irish born men were prominent at the highest levels of the British military. They were disproportionately from a military, landowning and Protestant background.

Similarly Anthony Durnford, the slain commander of the camp at Isandlwana, was born in Leitrim to an Army family, but educated in Germany and at the military academy at Woolwich, London, spending only one year of his adult life in Ireland.[14] Major John Wynne of Dublin, who died of disease at Eshowe, was the son of Royal Artillery captain and his mother was daughter of a Royal Navy Admiral. He too was educated at Woolwich and passed into the Army before his 19th birthday. [15]

Some others came from the great families of the Anglo Irish aristocracy. Nevill Coghill, who attempted to save the colours at Isandlwana, was the son of a Baron, and cousin of the Protestant Bishop of Meath. He was educated in England and after serving for two years in the Dublin militia, enlisted in the regular army in 1871. [16]

Captain Hugh Gough, of the Coldsteam Guards, who also died in the war of 1879 was the son of Viscount Gough of Galway. Robert Barton, who also fell in the campaign, serving in the same regiment, was originally of Glendalough County Wicklow. [17]

Others, particularly those who served in the colonial and native forces, had also adventured all over the British Empire.

John Dartnell, the son of military surgeon from County Limerick, was born in Canada, but served in the County Down Regiment, before later settling in South Africa, where he raised and commanded the Natal Mounted Police. [18]

George Hamilton Browne, who commanded the 3rd Regiment, Natal Native Contingent in 1879, was nicknamed ‘Maori’ for his prior service in the colonial wars in New Zealand. Brown, described in one source as a ‘hard bitten Irish contractor’[19] was born in Cheltenham in England, but was a member of a titled family with its seat at Comber House, County Derry.[20] After the Zulu campaign, he later served with Cecil Rhodes’ freelance expedition to conquer what is now Zimbabwe for the British Empire.

In Zululand, Hamilton Browne was known for his contempt for the African troops he commanded, openly referring to them as ‘niggers’, ‘curs’ and ‘scum’. He also developed a sour reputation for executing prisoners, torture and the burning of villages. [21]

So from this sample, it would seem, the higher ranking Irish officers in British forces in Zululand were mostly ‘Anglo-Irish’ Protestants from the military and the landowning elite in Ireland, themselves a kind of colonial class. For many, their Irish birth was not a matter of much more significance than those other officers who had been born in India or Jamaica.[22]

One of the most senior British officers in the Zulu War was Francis Clery, an Irish Catholic from Cork.

However this is not the full story. Some officers, including senior ones, were from the rising Irish Catholic middle class. Major Cornelius Francis Clery, for instance, was a Catholic, son of a wealthy Cork wine merchant, educated at the elite Catholic school at Clongowes College and later the military academy at Sandhurst. He was the senior staff officer on Chelmsford’s staff and later also commanded a Division in the Anglo-Boer War from 1900 to 1902. [23]

Captain David Moriarty, who was killed at Ntombe in March 1879, was the son of James and Catherine (nee Barry) Moriarty of Kilmallock County Limerick, who wanted him to study law, but he instead took a commission in the West York Militia at age 16 and the regular army at age 20. He was 42 at the times of his death, shot in the chest and shouting ‘fire away boys, I’m done’, as the Zulus overwhelmed his company.[24]

Irish Catholics had once faced legal barriers to serving in the armed forces (and voting), until 1795 and from holding public office until 1829 – restrictions that were in some ways analogous to those faced by ‘natives’ in British ruled southern Africa. However the Penal Laws were a thing of the past by the late 19th century – the Church of Ireland having been fully disestablished in 1869. By the time of the Zulu War, Irish Catholics faced no legal bar to service at the highest levels of the British military and colonial establishment and some, though disproportionately few in comparison to Irish Protestants, were availing of it.

Nationalist opposition to the war

Back in Ireland however, there was a substantial constituency that was steadfastly opposed to the British Empire and its wars.

The Anglo-Zulu War of 1879 coincided with the beginning of the ‘Land War’ in Ireland, a mass mobilisation of tenant farmers against eviction and for security of tenure, which was led by nationalists in the Land League (formed in August 1879) including the Fenian activist Michael Davitt and future leader of the Irish Home Rule Party, Charles Stuart Parnell.

The Land League and their followers certainly did not subscribe to a narrative whereby Ireland and the Irish were enthusiastic participants in the British Empire. Rather, for them Ireland was an occupied country and the landed class were a foreign, oppressive caste, who had taken the land by force in the wars of seventeenth century. One Land League activist, Fr. O’Malley of Neale, Mayo, rhetorically asked, ‘What is landlordism? The garrison of the enemy’. Some contrasted ‘humane old [Gaelic] aristocracy of Ireland’ with ‘Cromwell’s drummers, Highland pipers and Saxon pantry boys’.[25]

Radical Irish nationalists and Land League activists denounced the Zulu War as an act of aggression and cheered for Zulu victories.

The Land War was for the most part a campaign of boycott, mass meeting and agitation, but also of violent intimidation and on occasion, assassination of landlords, agents and ‘land grabbers’. On the other side, the police and military enabled landlords to carry out almost 12,000 evictions in 1879-80 and nearly 1,000 Land League activists were imprisoned. It was against this background that nationalist crowds and newspapers cheered the victories of the Zulus against the British.

Paul Townend has shown that crowds all over the country cheered the Zulus. From Navan in Meath, where Parnell addressed a rally, to a theatre performance in Dublin, where the crowd ‘hissed’ the Lord Lieutenant, to Land League meetings in Galway and Mayo, to Cork city where a lecture by war correspondent Archibald Forbes was disrupted, gave ‘three cheers for the Zulu king’. [26]

The radical nationalist press such as the pro-Fenian Flag of Ireland, denounced the invasion of Zululand as an ‘odious, predatory incursion upon the territory of a free people’ and hoped that ‘disaster might overtake the English’.[27] The Nation opined that the British were waging a ‘war of extermination such as they waged in the time of Elizabeth in Ireland, burning the homes of the people whose land they have invaded and hunting them down like brutes’. While the Connaught Telegraph similarly thought the war in South Africa was ‘exactly similar to the historic conquest of Ireland’.[28]

There was probably no truth to the rumour, reported in the press, that a former Fenian diamond miner ‘MacCarthy’ was fighting on the side of the Zulus, and certainly there was no pro-Zulu Irish contingent such as that which fought for the Boers against the British in South Africa twenty years later. But intriguingly, the Irish Republican Brotherhood, or Fenians, do seem to have discussed in secret the possibility of sending arms or money to aid the Zulus.

Some Irish Members of Parliament, including A.M. Sullivan of Louth praised the Zulus for their ‘patriotism’ and having ‘defended themselves’ against ‘aggressive imperialism’. Parnell himself stated that the war was ‘cruel and unjust’ and painted the ‘Irish peasant soldiers’ also as ‘victims of the holocaust of imperialism’.[29]

These were not universal sentiments in Ireland even among nationalists. The Limerick Reporter, for instance, counselled against hostility to those Irishmen who served in the British Army, ‘hatred of England cannot surely extend to those brave men who fight her wars?’ they reasoned. The unionist Cork Constitution deplored the ‘cheers for savages who massacred our fellow countrymen’. Even Fenians such as Davitt and the Nation, while otherwise praising the Zulu’s resistance to empire, were not above, at the same time, referring to them as ‘heathens’ and ‘savages’. [30]

Nevertheless, the apparently widespread identification in Ireland with the Zulu cause does call into the question the narrative that Ireland was a straightforward and enthusiastic participant in the British Empire, or that the Irish as ‘white’ automatically identified with other ‘whites’ politically. As Malachi O’Sullivan, the Land League activist put it in 1879, ‘the victims of the British bayonet, black or white, are sure to have the unqualified sympathy of all persons in Ireland’.[31]

Conclusion

To conclude, Ireland’s relationship with the Zulu War was complicated and contradictory, because Ireland’s place in the United Kingdom and the British Empire was itself complicated and contradictory. Ireland was in theory an integral part of the United Kingdom and its people equal citizens.

But in practice Ireland was governed by a semi-colonial regime in Dublin Castle with an armed police force and a military garrison. ‘Coercion’ or the suspension of normal peacetime law was a regular feature of Irish governance.

Irish born men, and at this date, they were all men, who participated in the military and administrative service of Empire were many. And though, at the upper levels, they came disproportionately from the Protestant community, the landed aristocracy and British military families, educated Irish Catholics increasingly also sought advancement in the service of Empire by the late nineteenth century, and some, such as Francis Clery were notably successful.

At the same time, Irish settlers to places such as South Africa enjoyed rights that the ‘natives’ did not possess.

On the other hand, many Irish nationalists, who undoubtedly represented a large section of public opinion, vociferously and repeatedly denounced Empire and all its works, and viewed Ireland not as a beneficiary, but as a victim of Empire. Under such circumstances, who was a ‘true Irishman’ becomes an ideological question as well as simply a matter of birthplace.

There is no way to iron these contradictions out of our understanding of Ireland’s past, for they existed, side by side in mutual contradiction of each other.

See also; Podcast: Ireland and the Zulu War and Ireland and South Africa, A tangled History.

References

[1] There is a detailed biographical information on British officer casulaties in, The South Africa Campaign of 1878/1879 By Ian Knight and Dr Adrian Greaves https://www.anglozuluwar.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Part_1__Zulu_War_Introduction.pdf

There is also a list includinf a picture and some biographical details of most of the officers who died in the war here. https://glosters.tripod.com/south.htm

[2] All above quotes cited in Paul Townend, Between Two Worlds, Irish nationalists and Imperial Crises, 1878-1880, Past and Present, February, 2007, No. 194. My thanks to David Flood for helping me obtain a copy of this paper.

[3] For a discussion of the rise of the Zulu Kingdom and its military system see Ian Knight, Brave Men’s Blood, The Epic of the Zulu War 1879, (1990) p20-23.

[4] Rorke married a Boer woman, Sara Strydom and had two children. James Rorke shot himself in 1875. By the time of the 1879 war, his home had become a mission station under Swedish missionary Otto Witt. Knight Companion to the Anglo Zulu War, p.172. A potted biography of the Rorke family is here.

[5] For a discussion of Frere and Shepstone’s engineering of a war against the Zulus, see Donald R Morris, The Washing of the Spears, The Rise and Fall of the Great Zulu Nation (Abacus 1992), pp.276-284, 289-294

[6] Many books have been written about the war, but I have principally consulted: Morris The Washing of the Spears, and Ian Knight’s books, Brave Men’s Blood, Zulu, Isandlwana and Rorke’s Drift, 22 January 1879 (1992) and The Companion to the Anglo Zulu War 1879 (2008).

[7] Morris, p.608-611

[8] The British Army did not formally change from numbered to regionally named regiments until 1881. Thus the 88th became the Connaught Rangers and the 24th, who fought the actions at Isandlwana and Rorke’s Drift became the South Wales Borderers.

[9] Graham Alexander, The Connaught Rangers. We had a deal of hard work, but no fighting https://www.anglozuluwar.com/images/Journal_18/The_Connaught_Rangers.pdf

[10] Ibid.

[11] Dan Harvey, A Bloody Night, the Irish at Rorke’s Drift, Merrion Press 2017. Reviewed here.

[12] Morris, The Washing of the Spears, p.238-244

[13]Sean William Gannon, Ireland’s Imperial Elites, Dublin review of Books

[14] Morris Washing of the Spears p.216

[15] Knight, Greaves, The South African Campaign, p.43

[16] Knight, Greaves, The South African Campaign, p.18

[17] Ibid. It is likely that he was related to the Irish nationalists of the 1920s Robert Barton and his cousin Erskine Childers

[18] Ian Knight, Zulu, p.13

[19] Morris, p.309

[20] Ian Knight, Companion to the Anglo-Zulu War, p.120-122

[21] Morris, pp.309, 449

[22] Several of the officers listed as having died in the South African Campaign were born in India. One officer Melville, who like Coghill died trying to save the colours at Isandlwana, was born in London, son of the Military Secretary of the East India Company. For reasons that are not entirely clear, he is commemorated in a memorial window at St Finbarr’s Cathedral in Cork. Another officer, Pope was born in in Jamaica and another in Australia.

[23] There are several short biographies of Clery online here, here and here.

[24] Knight, Greaves, The South African Campaign, p.34. Ian Knight, Brave Men’s Blood, p.123-124

[25] Joe Lee, The Modernisation of Irish Society pp94, 99. This narrative itself was full of contradictions. For a start, Parnell the leader of the Land League, was himself a Protestant and a landlord. Secondly by the late 19th century about 40% of landowners were Catholics and thirdly, some of the landlord class were themselves descended in whole in part from the old Gaelic aristocracy. However the narrative of the landlord class a foreign invaders and absentee landlords had enough truth to be a persuasive mass mobilising message.

[26] Paul Townend, Between Two Worlds, Irish nationalists and Imperial Crises, 1878-1880, Past and Present, February, 2007, No. 194. The following paragraphs are greatly indebted to Mr Townend’s article.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Ibid. Parnell’s reference to a ‘holocaust’ naturally to modern ears evokes comparisons with the Nazi genocide of Europe’s Jews in the 1940s, but the term was in use at the time in the nineteenth century for an event of great violence or slaughter.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Ibid.