The Battle of Tory Island – the last engagement of the United Irishman rebellion of 1798

By John Joe McGinley

The last battle of the United Irishman-led rebellion of 1798 was not fought, by Irishmen or even on an Irish battlefield, but at sea, off the stormy waters of Tory Island in a naval engagement between the French and British navies. History records this as the battle of Tory Island.

It is sometimes also known as the Battle of Donegal, The Battle of Lough Swilly and even Warren’s Action, but the British admiralty lists it as the battle of Tory Island. It was a naval action fought on the 12th of October 1798 just off the coast of Donegal in north western Ireland.

The battle was the confrontation between an attempted French invasion of Donegal in support of the Irish Rebellion of 1798, including a French squadron under Jean-Baptiste-François Bompart and a hastily assembled Royal Navy blockade squadron under Sir John Borlase Warren. (1)

The battle of Tory Island was a sea battle, off the coast of Donegal, between a French squadron, sent to aid the United Irishmen and Royal Navy blockading force.

Bompart’s force had been dispatched from Brest the month before with orders to reinforce a French army under General Jean Humbert which had landed two months earlier.

Tory Island, or simply Tory (officially known by its Irish name Toraigh), lies in the wild Atlantic nine miles off the northwest coast of County Donegal. It is a small island measuring just three miles in length and one mile across at its widest point. Tory Island was to see the last action in the struggle of the uprising of 1798.

The United Irishmen rebellion of 1798

The rebellion of 1798 was led by the United Irishmen, a republican revolutionary group heavily influenced by the philosophy of the leaders of the American and French revolutions.

The United Irishmen were established in 1791, first firstly the objectives of parliamentary reform based on universal male suffrage and complete Catholic emancipation. From 1795 however, after its banning, it was re-organised along secret, non-sectarian, and military lines, with the aim of ending British rule in Ireland, with aid from revolutionary France. (2)

A large French expedition sailed for Ireland in 1796 under the command of General Lazare Hoche, but storms scattered the fleet, and, though some ships reached Bantry Bay, no troops were landed.

French expeditions were sent to help the United Irishmen in 1796 and 1798, but despite this rebellion of 1798 was quashed by Crown forces.

By the spring of 1798, it appeared that Dublin Castle had been successful in its determined efforts to destroy the Society’s capacity for insurrection. Many of its leaders were in prison, its organisation was in disarray, and there seemed no possibility of French assistance. Despite these difficulties, on the night of the 23rd/24th May, as planned, the mail coaches leaving Dublin were seized – as a signal to those United Irishmen outside the capital that the time of the uprising had arrived. (3)

Serious fighting took place in east Ulster and Leinster, especially County Wexford, but by the end of June 1798, had mostly been put down by the forces of Crown. (4)

On the 22nd of August, a full two months after the rebellion had all but petered out the French surprised the British by landing 1,000 troops under the command of General Humbert at Kilcummin in County Mayo. Humbert was joined by 5,000 local troops and inflicted a humiliating defeat on the British force at Castlebar but was eventually defeated at Ballinamuck on September 8. (5) Humbert and his troops surrendered but many of the Irish insurgents were executed. (6)

The rebellion looked to be finally over, defeat for the United Irishmen had seen between 10,000 and 25,000 rebels (including a high proportion of non-combatants), and around 600 soldiers killed, and large areas of Ireland had been effectively laid waste. However, the final battle of the 1798 rebellion was still to come.

The involvement of France

France in 1798 was ruled by the ‘Directory’ that had governed the country since 1795, in the final stages of the French revolution. It came into power following the end of the National Convention and the excesses of the Reign of Terror and the Committee of Public Safety. It lasted until November of 1799 when it was overthrown by Napoleon Bonaparte.

The Directory consisted of an executive branch called the “Five Directors” and a legislative branch called the “Corps Legislatif.”

The Corps Legislatif was divided into two houses. The Council of Five Hundred and the Council of Ancients. The Council of Five Hundred proposed new laws while the Council of Ancients voted on the laws proposed by the Five Hundred.

France in 1798 was ruled by the ‘Directory’ that had governed the country since 1795, in the final stages of the French revolution. They sent aid to fellow republicans in Ireland and in retaliation for British aid to Royalists in France.

The Directory itself was ultimately controlled by Five Directors who were chosen by the Council of Ancients. They acted as the executive branch and were responsible for the day-to-day running of the country. (7)

As part of the coalition of European powers united against the French Republic and its ideals, Great Britain continued to aid French royalists seeking to destroy the republic. The Directory was continually looking for ways to counter the British threat to the Republic’s very existence.

General Hoche, the French General who had successfully defeated the British financed royalist rebellion in Vendee in 1795, wished to lead an assault on the British mainland as revenge for the continued British opposition of the French regime.

Hoche was lobbied by Irish patriots including Wolf Tone, who convinced him that a more suitable invasion target would be Ireland. The proposal was that if the French could land a force in Ireland, then the British would be forced onto the defensive. Irish forces would then rise in revolt, and a sister republic to the French Republic might be established.

It was Hoche who convinced the Directory to aid the Irish in their fight for independence, though he would die in 1797 and not witness the rebellion of 1798. (8)

The French send further aid.

Despite ending Humberts’ campaign at the battle of Ballinamuck in County Longford on the 8th of September, the British had been startled at the ease at which the French had landed in Mayo. They decided to monitor the French fleet closely, to ensure no other French troops could aid the now crumbling rebellion.

The French, unaware of Humbert’s defeat, had sent a small fleet of eight frigates led by the battleship Hoche and 3,000 men under the command of Commodore Jean-Baptiste-François Bompart.

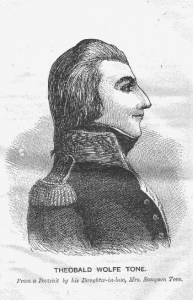

They were accompanied by the leading Irish revolutionary figure and one of the founding members of the United Irishmen, Theobald Wolfe Tone. He was serving as a gunnery officer aboard the flagship of the fleet, the Hoche.

The French fleet left Brest on the evening of the 16th of September. The plan was to land troops in Donegal to reinforce what they assumed to be a victorious Humbert, whom they hoped would now be sweeping through Connaught into Ulster.

The British Channel fleet was now on full alert to ensure no other French army would land by surprise in Ireland.

The French fleet left Brest on the 16th of September. The plan was to land troops in Donegal to reinforce General Humbert, who, unknown to them, had already surrendered.

This meant that despite Bompart’s fleet beginning their voyage under the cover of darkness, they were soon spotted by a British frigate squadron led by HMS Boadicea, captained by Richard Keats. He quickly set 2 of his ships, the frigates the Ethalion and the Sylph to follow the French while he rendezvoused with the main body of the Channel fleet, commanded by Admiral Sir John Borlase Warren.

The French were chased for a week into the Atlantic Ocean until they managed to lose the British in stormy seas. This extreme weather was to continue throughout the campaign, damaging ships on both sides and it would have a decisive impact on the final battle.

The British soon sent a Naval Squadron under Admiral Warren to the Donegal coast in search of the French fleet now heavily damaged by rough seas.

The battle of Tory Island begins

The British finally caught up with the French off the North West of Donegal, on the morning of the 12th of October 1798. The French commander Bompart now found himself surrounded on all sides by a vastly superior British force and was engaged in a naval battle off Tory Island.

The French fleet tried to escape and went under full sail to get away, but the British were soon in hot pursuit and gaining ground. Bompart the French commander tried to distract the British by ordering the weather damaged frigate Résolue commanded by Captain Jean-Pierre Bargeau to be beached on Tory. The commander ignored the order, perhaps thinking capture was better than the danger of beaching on Tory in atrocious conditions.

The French commander Bompart found himself surrounded on all sides by a vastly superior British force and was engaged in naval battle off Tory Island.

In the morning Warren was still hard behind Bompart, whose ships were now sailing in two uneven lines. Warren’s force was even more dispersed, with HMS Robust and HMS Magnanime 4 nautical miles (7.4 km) astern of the French and gaining fast, HMS Amelia and HMS Melampus shortly behind them and Warren’s flagship HMS Canada with HMS Foudroyant under Captain Sir Thomas Byard, 8 nautical miles (15 km) from the enemy. The other British ships were scattered throughout this formation except HMS Anson, which was wallowing to the rear, far out of sight. (9)

Bompart asked Wolfe Tone if he would like to embark on one of the faster frigates and perhaps secure his freedom, but Tone bravely refused and decided to stay and fight.

The French commander now had no other option than to attack the British fleet head-on and hope that some of his fleet could punch a way through and escape the British guns, which were now bearing down on them. He formed his squadron into a battle line and turned westwards, waiting for Warren’s signal for the attack.

However, the French faced a fine seaman in Admiral Warren, and he had his own plan of action prepared.

At 7.00 on the morning of 12th October, Admiral Warren ordered the British warship HMS Robust to head straight for the French flagship Hoche. Captain Edward Thornbrough of Robust obeyed immediately and closed with the French, firing into the French frigates, Embuscade and Coquille, as they passed, before closing on the Hoche and, at 08:50, beginning a bitter close-range artillery duel.

This clever manoeuvre created space for the British warships HMS Ethalion, Melampus and Amelia to concentrate fire on the Hoche, which was now isolated and vulnerable.

Meanwhile while the British ship HMS Magnanime engaged the French frigates Immortalité, Loire, and Beltone. (10)

The French Surrender

The Hoche was heavily storm damaged, having lost a topmast earlier. When the British realized just how severely damaged the Hoche was, they began to pound it with broadsides from their cannon.

Less than four hours after it had begun, the Battle of Tory Island ended when the Hoche surrendered at 10.50am. She was drifting low in the water and 270 of its crew were either dead or seriously injured.

The French ship Embuscade was the next to surrender, having been battered in the opening exchanges by Magnanime, and further damaged by long-range fire from Foudroyant during the pursuit.

Overhauled by several larger British ships, Captain de la Ronciére surrendered at 11:30 rather than allow his ship to be destroyed.

After the French surrendered, among those captured was leading United Irishman Theobald Wolfe Tone, who died by suicide in prison shortly afterwards.

HMS Magnanime, suffering the effects of her engagement with the Hoche, took possession of Embuscade and continued to follow slowly behind the rest of the fleet, while HMS Robust, which had suffered severely in her duel with Hoche, remained alongside her French opponent to take possession of the enemy’s flagship.

The remaining French ships began to flee; however, the direction of the wind took them across the path of the straggling British ships, beginning with the HMS Foudroyant. Most of the frigates were able outrun the British pursuers, but the French ship Bellone was less fortunate and a speculative shot from a British battleship detonated a case of grenades in one of her topmasts. This began a disastrous fire which was eventually brought under control, but at a significant cost in speed. She was soon closely attacked by Melampus and suffered further damage.

Nearby, the struggling Coquille surrendered after being outrun by the approaching HMS Canada. Admiral Warren ordered the slowly following HMS Magnanime to take possession.

HMS Ethalion took over pursuit of Bellone from Melampus, and for two hours maintained continuous fire on the French ship. Ethalion was faster than her quarry, and she gently pulled parallel with Bellone during the afternoon but could not get close enough for a decisive blow. It took another two hours of pursuit before the battered Bellone eventually surrendered. (11)

Hoche apart, Bellone had suffered more casualties than any other ship present.

During the evening, the surviving French frigates gradually pulled away from their pursuers and disappeared into the gathering night, leaving behind four of their squadron, including their flagship, as captives. (12)

Wolfe Tone’s mission had failed, the French flagship and four Frigates had been captured, while the surviving French ships ran scattered around the Donegal coast trying to make to safety. The prisoners were landed at Buncrana in Lough Swilly, which was used as a British naval base until the final surrender of the Treaty ports in 1938.

The final blow for the United Irishmen came with the arrest of Wolfe Tone who was recognized by Sir George Hill. Tone was identified dressed in a French adjutant-general’s uniform in Lord Cavan’s home in Letterkenny.

Tone was immediately arrested on charges of treason and sent to Dublin for trial. He was sentenced to death but mysteriously committed suicide before the sentence could be carried out.

Battle of Tory Island – Aftermath

The remaining French ships desperately evaded the pursuing British naval squadron as they tried to reach the safety of French-controlled harbours. Of the six French vessels the British captured three and the others made it to safety. The losses at the Battle of Tory Island ensured that never again would the French attempt an invasion of Ireland.

One other impact of the 1798 rebellion was Prime Minister William Pitt’s Act of Union, which abolished the Irish Parliament, Ireland being henceforth represented in the British Parliament at Westminster.

The victors of the Battle of Tory Island were well rewarded monetarily and with promotions and honours.

The victors of the Battle of Tory Island were well rewarded monetarily with the proceeds from selling the captured French ships. The French Flagship Hoche was renamed HMS Donegal.

The French frigate Coquille was intended for purchase but suffered a catastrophic ammunition explosion in December 1798, which killed 13 people and totally destroyed the vessel. The last two prizes, Résolue and Bellone, were deemed too old and damaged to be worthy of active service. They were, however, purchased by the Royal Navy to provide their captors with prize money, Bellone becoming HMS Proserpine and Résolue becoming HMS Resolue. Both ships served as harbour vessels for some years until they were broken up. (13)

Admiral Warren received the thanks of parliament and many junior officers were promoted.

In 1847 the battle was among the naval engagements recognized by the clasp, “12th October 1798”, attached to the Naval General Service Medal, awarded to all the surviving British participants of the Battle of Tory Island. (14)

The British victory in the Battle of Tory Island finally ended the United Irishman rebellion of 1798. The losses faced by the Irish forces during the rebellion coupled with the reprisals meted out by the British against anyone who had aided the uprising ensured that the flame of rebellion was dampened in Ireland for many years but never extinguished.

John Joe McGinley March 2021

Sources:

- The Frigates. Leo Cooper 1970

- Irish History 1798 Britannia.com

- The 1798 rebellion Professor Thomas Bartlett

- 4.Harvey, R (2007). War of Wars: The Epic Struggle Between Britain and France 1789–1815. London.

- Harvey, R (2007). War of Wars: The Epic Struggle Between Britain and France 1789–1815. London.

- Wickwire, Franklin and Mary (1980). Cornwallis: The Imperial Years

- Edward Baines History of the Wars of the French Revolution.

- Valerian Gribayedoff The French Invasion of Ireland in ’98

- Richard Brooks. Cassell’s Battlefields of Britain & Ireland (2005)

- The Biographical Memoir of Sir John Borlase Warren, Bart, K.B. Tracy, p. 286,

- Robert Gardiner Nelson Against Napoleon: From the Nile to Copenhagen, 1798–1801

- Robert Gardiner Nelson Against Napoleon: From the Nile to Copenhagen, 1798–1801

- Bernard Ireland, Naval Warfare in the Age of Sail: War at Sea, 1756–1815 (2000)

- The London Gazette. 26 January 1849.