‘They were determined to obtain a sacrifice’: First Irish state executions of IRA members since the Civil War

By Gerard Shannon

It was the night of 16 August 1940 and a worried Christy Quearney cycled through Dublin city’s southside.

Quearney, a member of the IRA’s Training Department, was frequently on the move these last few months. He knew well his membership of the IRA, and associated activities, put him at risk of great interest from the state authorities.

His intended destination was an address at Rathgar Road, which for the last two years had functioned as the HQ for the IRA’s underground Training Department. One of its current occupants included the IRA’s Director of Training, Paddy McGrath, a veteran of the earlier revolutionary period in Ireland from 1916-23.[1]

From the outside, the two-story premises at 98a Rathgar Road resembled an ordinary tobacconist shop. A plywood partition behind the counter separated the shop from a large living premises. In the flat above, were three bedrooms and a bathroom, where much of the work of the Training Department was carried out.[2]

A Garda raid on an IRA safehouse in south Dublin in 1940 resulted in the ultimate death of four men.

On a previous visit, Quearney had spied a known Garda detective in a doorway across the road from the Training HQ. Quearney, like other active IRA members, often travelled across the city on a bicycle, which could have resulted in any of them been tailed back to the residence. To his surprise, on mentioning this possibility recently to one occupant of 98a Rathgar Road, it was dismissed. Under the Irish government’s Offences Against the State act, the Gardaí would require little obstruction to be allowed raid the premises in the event of any suspicion of ‘subversive activity’.

An increasingly on edge Quearney noticed a crowd had gathered outside the shop on his arrival. Surmising some sort of incident had just transpired, Quearney dismounted and stood at the edge of the crowd. He asked a man what had taken place. ‘German spies’ came the reply, a not uncommon paranoia among the Irish public at the time.

Knowing full well that a Garda raid on the premises was more likely to have occurred – along with the inevitable response from his comrades inside – Quearney quickly mounted his bicycle and departed back towards the city centre. Later piecing together events, Quearney noted ruefully 98a Rathgar Road was a ‘fateful house really; four men were to die over it’. [3]

Two of these were IRA Volunteers put to death by state execution, Paddy McGrath and Thomas Harte. Their deaths were to mark a profound policy shift in how the Irish government were to deal with the IRA during what it officially referred to as ‘the Emergency’ of 1938-45.

Political Background

At the outset of the Second World War, the IRA operating in Éire (formerly the Irish Free State) was a pale shadow of the revolutionary force of 1913-23.

In the near two decades since the Civil War, it faced dwindling membership, political splits and continued repression by both states on the island. In 1938, the charismatic and devoutly militant Seán Russell ascended to the position of IRA Chief-of-Staff and with his allies devised and directed the IRA to carry an ill-advised bombing campaign in England between 1939 and 1940.

While terrorising a frightened British populace on the eve of conflict with Germany, the main results of this campaign was to be civilian loss of life, along with mass arrests and imprisonment of IRA suspects.

In August 1940, Russell himself died ingloriously of a burst stomach ulcer whilst travelling aboard a German U-Boat returning him to Ireland. Russell had spent a period in Berlin meeting representatives of the Nazi government with muddled results, in keeping with the republican dictum that, ‘England’s difficulty is Ireland’s opportunity’. The late Russell left behind him an IRA in disarray in face of multiple threats.

The IRA, which imperilled Irish neutrality by its contacts with Nazi Germany, was subject to harsh repression by the Dublin government throughout the Second World War.

The IRA was still determined to fight for full Irish independence and refused to recognise the legitimacy of either of the existing states in Ireland. In Northern Ireland, the IRA faced repression, arrests and even one execution by the Stormont government in this period, but it met with the greatest repression by the Fianna Fáil government headed by Éamon de Valera in the jurisdiction of Éire.

De Valera, himself a veteran of the 1916 Easter Rising and leader of the earlier revolutionary movement, certainly boasted considerable republican pedigree himself, along with many then serving in his cabinet. He had headed government since 1932 and had legalised the IRA and reconciled many anti-Treaty republicans to the Irish state, but a hardcore of the IRA remained irreconcilable. By 1939, (having banned the organisation again in 1936), de Valera was long past trying to reconcile the IRA and any former comrades to the institutions of the state.

At the outset of the Second World War, in which the Irish state proclaimed neutrality, the government declared a ‘national emergency’ and introduced several critical items of legislation to combat the IRA, whose contacts with Nazi Germany they saw as a clear and viable threat to the state.

The first was the Offences Against the State Act, introduced in 1939. which allowed for people to be brought before new special military courts for a variety of offences. including membership of proscribed organisations or the obstruction of the government or its servants. The new Act also allowed increased the state’s power of search, arrest and detention, which included the use of internment without trial.[4]

The Emergency Powers Act, in 1940, as noted by Eunan O’Halpin, ‘conveyed very wide powers on the government to act by emergency order in every aspect of national life.’ This included allowing for state execution following convictions for an array of different offences. One of these was the capital charge of killing a member of the police force, An Garda Síochána.[5]

Thus, mass arrests and imprisonment were to be frequent for the IRA in the coming years. Even a rare success such as its raid on the Irish Army weapons store on the Magazine Fort in the Phoenix Park on Christmas Day, 1939, was short lived and ended with the later recapture of much of the haul of ammunition by the authorities.

By the autumn of 1940, the IRA had witnessed already the deaths of two IRA volunteers on hunger strike in Mountjoy. Others, including Paddy McGrath, had been released by the government along with other republican prisoners after a dramatic 42-day hunger strike in Mountjoy the previous November.

Violent entanglements with the Gardaí, were also commonplace by the time of the raid on Rathgar Road. In January 1940, a leading member of the IRA Executive, Tomás Óg Mac Curtain, had shot dead Detective John Roche following an attempted arrest of Mac Curtain in Cork city centre. Considerable lobbying of the government from a cross-section of Irish society had allowed for the still-imprisoned Mac Curtain to be granted clemency from execution. Mac Curtain being the son and namesake of the Cork Lord Mayor murdered by British forces during the War of Independence undoubtedly played a part in saving him.[6]

The raid

The raid on the IRA safe house in Rathgar was thus part of an ongoing wave of repression aimed at the IRA by the Dublin government.

The state’s case at the subsequent trials of Harte and McGrath laid out the following narrative: On the night of 16 August 1940, three Garda detectives – Patrick McKeown, Richard Hyland and Michael Brady – called to the door of the premises on 98a Rathgar Road. Meanwhile, two of their colleagues went to the rear of the house.

On knocking, a young man opened the door, and asked the Gardaí who they were. Noting six milk bottles on the ground outside, the man went to pick them up but Detective Hyland told them to leave them and pushed him back into the shop. As Detective McKeown held the young man, Detectives Brady and Hyland entered the shop and proceeded towards to the partition. The men little realised they had been deliberately delayed from entering, when a burst of gunfire suddenly rang out.

Two Garda detectives were killed in the shootout at Rathgar Road and three IRA men captured.

Detective Hyland, who had been behind Brady, managed to fire one bullet in response before being hit seven times. A bloodied Hyland collapsed on the shop floor, behind the counter. Detective McKeown had been hit in the stomach, yet miraculously still managed to turn around and run out the door. Detective Brady, meanwhile, had managed to crawl out the door, having been shot in the spine.

Three IRA members ran out the front door. One, later determined to be Paddy McGrath, was carrying a Thompson submachine gun. As the two Gardaí who had been at the rear of the house were alerted to the noise and gave chase, at least one of the IRA men was said to have fired back.

At the corner of Wesley Avenue, one of the pursuing Gardai fired, managing to hit one of the fugitives. Two of the IRA members were caught while recuperating in a nearby laneway, the younger of the two clearly limping.[7]

The third IRA man to escape, 21 year-old Thomas Hunt, was located and arrested six days later.[8]

One republican narrative of the event suggested the Garda detectives entered the building and began firing wildly. As the IRA members inside fired back, Thomas Harte was wounded in the building while those inside managed to make their escape. On noting his absence, McGrath returned to the shop to his fallen comrade to enable his escape, resulting in their arrest nearby.[9]

Muddying the waters further, no inquest was held for the dead Garda detectives, and the results of an internal inquiry was suppressed by Minister for Justice Gerald Boland. This was to give rise to a belief the detectives were not killed by bullets fired by the IRA, and no official attempt was made to determine if McGrath and Harte fired the fatal shots.[10]

What can be said with certainty is that two men died at the scene, and another two were to pay the price. Who were the four men whose fates were ultimately shaped by this incident?

McGrath and Harte

At the outset of the IRA’s bombing campaign from 1939-40, Chief-of-Staff Seán Russell had managed to coax back to the IRA several veterans of the earlier 1916-23 period. One veteran to return to the ranks was Paddy MacGrath, who became his adjutant-general and the IRA’s Director of Training. As Director of Training, McGrath was responsible for ensuring strict discipline among the Volunteers in the use of arms and explosives.

MacGrath had built up a considerable prestige during the earlier revolutionary period; in fact, he and three of his brothers had also taken part in different roles within the militant ranks of the republican movement from 1916-1923.[11]

McGrath himself joined the Irish Volunteers in October 1915, and he was to serve as a member of the Four Courts Garrison under the command of Ned Daly during the 1916 Easter Rising. Subsequently imprisoned in Frongoch, McGrath, following his release, became a first-lieutenant in the Fifth Battalion of the Dublin Brigade.

Paddy McGrath was a veteran of the 1916 Rising, War of Independence and Civil War. He rejoined the IRA in the late 1930s

According to his military pension application, McGrath in February 1920 suffered a serious injury following an encounter with police detectives near College Green. McGrath had just taken part in an unsuccessful raid to destroy arms stores belonging to the RIC Auxiliaries in North Wall. In the confrontation that followed, McGrath received a gunshot wound to the left shoulder at the base of his neck. As well as an initial award of £1500, McGrath received a wound pension of £200 per annum by the Pensions Board.[12]

Siding with the anti-Treaty IRA in the Civil War, McGrath was arrested and imprisoned in February 1923. At the time of his arrest, he had been involved in a subsequently abandoned plot to kidnap W.T. Cosgrave, the head of the Free State government.[13] His fellow prisoner Pax Ó’Faoláin, who was involved with McGrath in a failed attempt at creating an escape tunnel in prison, was struck by McGrath’s personality despite his disability: ‘He was a most ingenious fellow, extremely clever with his hand. He had only one, but it was extraordinary what he could do with it. …He was extremely plucky and courageous.’[14]

McGrath had clearly never envisaged a return to the IRA after the Civil War, given that he applied (and received) a state military pension in the 1920s – something usually not pursued by republicans who refused to recognise the new Irish state.

However in the late 1930s, Sean Russell convinced McGrath to return to the IRA, McGrath then running his window blind business at his residence on 17 Aungier Street. One of those on McGrath’s staff, Christy Quearney, was concerned that McGrath’s time away from the republican movement perhaps blinded him to certain on-the-ground realities of the IRA by the late 1930s.

Quearney ‘could see no sense in open warfare against the Free State Army or the Free State police; it would get us nowhere. We were unable to carry on the fight on one front, let alone two. That had been my point all the time that it just was not on. I had quite an argument with Paddy on that. … to Paddy… this was a continuation of the Civil War, and that Paddy was still fighting that war.’[15]

The younger of the two men arrested after the raid on Rathgar Road, was 24 year old Thomas Harte. Born in Lurgan, Co. Armagh, in May 1916.

McGrath was interred in Arbour Hill prison under the government’s legislation in late 1939. His presence among a growing cadre of republican prisoners resulted in McGrath leading a number of over 150 IRA men on hunger strike.

The Labour party pushed for McGrath’s release, while within Fianna Fáil there was unease given McGrath’s status as a 1916 veteran. Liam Tobin, a leading figure within the so-called army mutiny in 1924, pushed McGrath’s record and that of his family in the ‘national struggle’, emphasising it ‘would be a tragedy if he lost his life, no matter what we may think of the aims and methods pursued by himself and those associated with him.’

In early December 1939, de Valera’s government released the striking prisoners unconditionally, likely due to its view the IRA was in reality little threat to the state. McGrath had been on the forty-second day of his hunger strike.[16] However, de Valera may have come to regret the move, given the IRA’s daring raid on the Magazine Fort in the Phoenix Park on Christmas Day, 1939, in which large quantities of Irish Army ammunition was seized by the IRA – both a shock and humiliation to the government.[17]

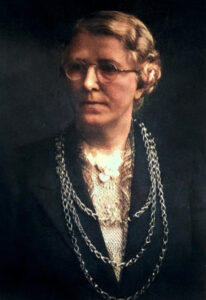

One major campaigner ‘overjoyed’ at McGrath’s release, was Kathleen Clarke. Clarke was the widow of the executed Rising leader, Thomas Clarke, but also a major public figure in her own right, then Dublin Lord Mayor and a founding member of Fianna Fáil. Meeting McGrath for the first time at his bedside while he recovering in Jervis Street Hospital, she was ‘very impressed with his nobility.’ McGrath told her he would have seen the hunger strike through to the finish.[18]

The younger of the two men arrested after the raid on Rathgar Road, was Thomas Harte. Born in Lurgan, Co. Armagh, in May 1916, the twenty-four-year-old Harte, had been sent by Russell to part in the bombing campaign in England. Arrested by police there in 1939, Harte gave his name as ‘Tom Green’, and deported back to Dublin. On his return to Ireland, Harte worked as an organiser for IRA General Headquarters. It was in this capacity he was in the residence on Rathgar Road on the fateful night.

The Gardaí

The two Garda detectives killed at Rathgar Road, similarly to McGrath, could claim involvement in the revolutionary period.

Patrick McKeown was a single man, and served as a Gardaí in Blackrock and Dún Laoghaire in Dublin. McKeown was born in Clea, just outside Keady in south Armagh. With the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty in early 1922, McKeown and his brother crossed the border into Monaghan, and there enlisted in the new National Army of the Irish Free State. Following the end of the Civil War, McKeown joined the new police force and by 1939, had achieved the rank of detective sergeant.[19]

On being brought to Meath Hospital in the aftermath of the shooting, McKeown was conscious and was operated on that afternoon. A bullet had hit a rib, which entered his abdomen, which was further inflamed after peritonitis set in. He died several hours later.[20]

Garda detectives Richard Hyland and Patrick McKeown were also veterans of the Irish revolutionary period.

His colleague, Richard Hyland, had been killed instantly. One of the seven bullets that hit him entered his forehead, lacerating his brain.[21] The 36 year-old Hyland was born in Manulla, Co. Mayo, spending much of his youth in Maynooth, Co. Kildare. During the War of Independence, Hyland was quartermaster of ‘E’ Company, 2nd Battalion, Dublin Brigade, IRA, and was to subsequently take part in the republican military resistance to the nascent Free State during the Civil War.

Following Fianna Fáil’s election in 1932, numerous anti-Treaty IRA veterans such as Hyland, previously suspected by the police as subversives, joined the Gardaí, in an effort to create a force loyal to the new governing party. As a member of the Special Branch, Hyland was stationed in Dublin Castle. On his death, he was a resident of Drimnagh, south Dublin and was a father of two children under the age of 3.[22]

The funeral for both men was held at the Carmellite Church on Whitefriars Street, Dublin on August 18. Between 400 and 500 members of the Gardaí attended, along with four government ministers. McKeown was buried in his family plot in his native Keady, while Hyland was buried in Glasnevin cemetery.[23]

Both men are listed on memorial based in Dublin castle to all Gardaí killed in the line of duty since the state’s foundation. Along with their aforementioned colleague John Roche, three more Gardaí were to be shot dead by IRA members in separate instances before the end of the Emergency: Denis O’Brien (another anti-Treaty IRA veteran), Michael Walsh, and George Mourdant. Further state executions of republicans were to follow these shootings.

Arrest and Execution

McGrath was arrested just around the corner from the shootout on Rathgar Road, with the injured Harte.

Now in custody, on his way to Bridewell Station, McGrath allegedly said to the arresting Gardaí: ‘I suppose you men don’t know who I am. I am Patrick McGrath. You got the spoils this morning. I am surprised at you men coming to a house where there are Republican soldiers, knowing that they were armed. You have started the shooting… We are taking no chances now.’[24]

If McGrath’s statement is to be believed, he expressed no qualms as to the action he undertook, particularly his linking to the deaths to recent incidents involving republicans. He would also allude to this in a final letter to his sister (see below).

The military court, the first of its kind under the emergency legislation, was held only four days after the raid on Rathgar Road.

The trial for McGrath and Harte convened at Collins’ Barracks, where the latter, given his injuries, had to be carried in on a stretcher. While the judge gave both men the opportunity to defend themselves, both refused to recognise the court and wished for no assistance in their defence. Nonetheless, a plea of not guilty was entered on their behalf. Both were only charged with the murder of Detective Hyland with the bullets from his body matched to a gun allegedly fired by Harte.

Despite a legal defence by Sean MacBride and a campaign for clemency by figures such as Kathleen Clarke, McGrath and Harte were executed by firing squad on September 6 1940.

After only fifteen minutes of deliberation by the jury, the men were sentenced to death.[25]

Kathleen Clarke, in her capacity as Dublin Lord Mayor, met Minister of Justice Gerald Boland, to lobby for the release of both men. Both were also party colleagues in Fianna Fail. Boland made clear there was nothing he could do to halt the executions. Clarke felt that ‘in executing men like McGrath, the government was carrying out the old British policy of killing or exterminating in one way or another all the best of our people.’[26] Indeed, McGrath was well known to Boland, given their shared service in the Dublin IRA during War of Independence and Civil War.[27]

Kathleen Clarke also allowed use of the Lord Mayor’s residence, the Mansion House, by a relief committee to campaign for the men’s release.[28]

One handbill from this relief committee reminded those supporting their efforts that both men ‘are prepared and will face the firing squad with full conviction and confidence in their ideal, freedom of the whole Irish Nation from England.’ The handbill added ‘think also of the horror of the whole country of the inception of yet another era of executions!’[29]

A leader in this campaign was the lawyer Seán MacBride, himself a former IRA Chief-of-Staff. While he had disassociated from his former organisation and actually supported the state’s neutrality, MacBride felt for various reasons, any proposed executions of republicans in the current political climate was unjustified.[30] MacBride was to prove himself a brilliant, gifted defender for subsequent, similar cases for republicans and in this instance managed to successfully delay McGrath and Harte’s executions, (which were due to be carried out within 48 hours of the verdict).

MacBride made efforts to cast doubt over the validity of the trial proceedings on various points, arguing that as there was no state of war in the country at the time, the military court was unlawful. Hence, this made McGrath and Harte ordinary citizens and not amenable to military law.

Nonetheless, on 26 August, Mr. Justice Gavan Duffy decreed the verdict was lawful under the emergency legislation and rejected the appeal. The appeal to this decision was rejected by the Supreme Court on the 4 September, with the executions due to take place before a firing squad on the 6 September.[31] Of his efforts, MacBride later commented, that ‘we fought that case on every available pretext for three weeks, but we could not save them. They [the government] were determined to obtain a sacrifice after what happened at Rathgar Road.’[32]

On 4 September, after a meeting lasting three quarters of an hour, de Valera’s cabinet met at Government Buildings to decide whether to commute the sentences of McGrath and Harte. The cabinet made a collective decision to contact the adjutant-general of the military court to allow for the death sentence on both men to be carried out. In the view of Donnacha Ó’Beacháin, this was undoubtedly a ‘momentous decision’ given Fianna Fáil’s history and the revolutionary activities of many sitting around the cabinet table.[33]

Thus, the state was carry out the first executions of IRA members since the Civil War. In 1922-23, it was a government led by the pro-Treaty Cumann na Gaedheal party which oversaw the executions of eighty republicans. All these executed republicans had been ideological comrades of de Valera and much of his cabinet.

The IRA’s general unpopularity in 1940 greatly impacted the prospect of a considerable public outcry to the execution of McGrath and Harte, but wartime censorship also played a part. For example, the Irish Times omitted any mention of the pair’s IRA membership and merely stated: ‘Following the rejection of the Supreme Court of the appeal on behalf of Patrick McGrath and Thomas Hart (sic)… the Government has fixed Friday, September 6th for the carrying out of sentences of death imposed by the Military Court… ’[34]

In his letter to his sister, McGrath remarked that he and Harte were denied a chance to address the court after their sentencing. A selection from this letter revealed the rough statement he had hoped to deliver on their behalf:

‘You are all Irishmen – most of you are soldiers. We, too, are Irishmen and soldiers. Now that you have done what you believe to be your duty we wish to say that we have also done what we believe to be our duty… ’

While expressing regret for the death of Hyland and McKeown, McGrath argued ‘those men decided to brand as criminals, us, the soldiers of the Irish Republican Army and their former faithful comrades, they made a grave error.’[35] Of note, McGrath did not deny his own culpability in their deaths.

The night before his execution, Harte wrote to his mother, ‘I am writing my last letter to you, because I thought more of you than any other person on earth… you know I was always strongly republican, was always thinking out ways and means of furthering republican ideals… if I fought for my country, it was for the poor downtrodden people of Ireland…’[36] Incredibly, Harte’s family in Armagh only heard of the pending execution from a family friend two days before, and not from a communication by the Irish government.[37]

On the morning of both men’s execution in Mountjoy Jail, fellow republican prisoner John J. Hoey recalled it was ‘a nice bright and sunny morning.’ Despite this, Hoey recalled how that day the other republican prisoners has ceased all their usual leisure activities in the yards, with ‘no loud talk or laughing’ among them.[38]

Another republican internee, Tony McInerney, from his cell recalled hearing the ‘shuffling as they [McGrath and Harte] were led out’ and the volley of shots that followed. McInerney recalled how ‘a terrible gloom descended then upon the entire prison’ following this.[39]

Fr. John McLaughlin, the Army chaplain, attended the executions. In a later written account, he claimed the officer in charge of the twelve-man firing squad, was, like McGrath, a veteran of the Easter Rising, and ‘deeply affected’ by having to carry out his former comrade’s execution.[40]

Following the executions, the republican prisoners met in one of the empty huts to pay tribute as a group to the memory of McGrath and Harte. There, George Plunkett, brother of one of the executed leaders of the 1916 Easter Rising, Joseph Mary Plunkett, gave the oration.[41]

McInerney was of the opinion given the considerable impact the executions had on the imprisoned republicans within the jail, all future executions of IRA members took place instead at Portlaoise Prison.[42] The remains of both men were to lie buried in the grounds of Mountjoy for nearly a decade, McGrath’s body having been placed in the coffin originally intended for Tomás Óg MacCurtain, prior to his reprieve.[43]

On their executions, Kathleen Clarke had the blinds in the Mansion House drawn and ordered the City Manager to have the national flag flown at half-mast at City Hall. Clarke was in no doubt this damaged her relationship with de Valera and the Fianna Fáil leadership.[44] The treatment of imprisoned republicans in this period appeared to contribute to Clarke’s disillusionment with a party she helped found, and she subsequently resigned from the party in 1943.[45]

The third IRA volunteer arrested following the raid on Rathgar Road, 21 year-old Thomas Hunt, was also later defended by MacBride at a military court. MacBride protested strongly at convening Hunt’s trial the day after the executions of McGrath and Harte, thereby depriving Hunt of two key witnesses. Though being found guilty, the government ultimately granted Hunt a last-minute reprieve and sentenced him to penal servitude for life.[46]

Legacy

By the late 1940s, the IRA as an organisation was decimated and demoralised. Its contacts with the Nazi government during the Emergency had come to naught, and its ill-fated bombing campaign in England was to prove an utter failure. A combination of internment, bad leadership, lack of resources, and sheer ill-luck had greatly reduced its capacity and effectiveness in its aims.

By 1946, the most recent phase of activity in the jurisdiction of Éire had seen six of members executed and three dead on hunger strike. Remarkably, only two years after the execution of McGrath and Harte, de Valera’s government had protested the execution of 19 year-old IRA Volunteer Thomas Williams on the orders of the government of Northern Ireland.

In 1948, a new Irish coalition government which included the republican Clann na Poblachta, released the remains of IRA men executed by the state in the last decade from the prison grounds to their families. Such an effort had been lobbied by the republican commemorative group, the National Graves Association.[47] The sites of their various burials all took place in different locations across Ireland on 18 September, 1948. Each became massive gatherings for members of the republican faithful and in some ways, brought the names of these men more into the public domain not previously possible under the wartime censorship.

Harte’s funeral was the only one to take place within Northern Ireland, in his native Lurgan, Co. Armagh. The RUC interrupted the funeral procession and forcibly removed the tricolour from the hearse that had draped the coffin.

At the oration by his graveside, the republican Ruairí Ó’Drisceoil said of the youthful Harte’s inspiration to join the IRA: ‘It was not long till he realised that not only had we not achieved… freedom… but that the position was, if anything, worsened in so much as we… had a British-imposed border on either side of which a dominion government ruled Ireland.’[48]

At McGrath’s own reinterment in the Republican Plot in Glasnevin cemetery, an impressive crowd of hundreds assembled. Ironically, in close vicinity in the Republican Plot lay buried Garda Richard Hyland, killed at Rathgar Road on that fateful night, himself being an anti-Treaty IRA veteran, just like Paddy McGrath.[49]

The republican stalwart, Brian O’Higgins addressed the crowd, couching his oration in emotive language typical of such events. O’Higgins felt there ‘is no need, in the presence of those who knew him, to speak the praises of Paddy McGrath. He… might be said to typify unswerving fidelity to the cause of Ireland indivisible and free… ‘

Today only commemorated in the most devout republican circles, the names of McGrath and Harte are listed on plaques at the base of the statue to IRA Chief-of-Staff Seán Russell in Fairview Park

Noting the Irish state’s role in allowing the reinterments take place, O’Higgins mischievously indicated this was the coalition government’s way of acknowledging the executed republicans as ‘men of honour and integrity, as unselfish soldiers who died in defence of the cause to which they have given their allegiance.’

He ended with a derision of the coalition government’s declaration of the Republic of Ireland that had taken place that year, firmly resulting in a final constitutional break between the jurisdiction of the former Irish Free State and the British Commonwealth.

‘Men talk foolishly today, as they and others have talked for many futile years, of ‘declaring’ the Republic of Ireland. There is no need to declare it.’ Noting the establishment of Dáil Éireann in 1919, O’Higgins argued that Republic declared then ‘has never been destabilised since, but it has supressed by falsehood and force, and it is supressed at this present moment.’ Invoking McGrath and his executed comrades of the period, O’Higgins closed with the statement their ‘blood cries out for one vengeance – the restoration of the supressed Republic of Ireland.’[50]

Two ministers of the coalition government were in the crowd that day, Clann na Poblachta’s Noel Browne and Seán MacBride; MacBride of course having led the legal appeal on behalf of McGrath and Harte.

Today only commemorated in the most devout republican circles, the names of McGrath and Harte are listed on plaques at the base of the statue to IRA Chief-of-Staff Seán Russell in Fairview Park; the only major memorial encompassing IRA men dead by execution or hunger strike in the 1940s.

References

[1] See Uinseann MacEoin, The IRA in the Twilight Years 1923-1948, (Dublin, 1997), pages 776-777.

[2] Colm Wallace, The Fallen: Gardaí Killed in Service 1922-49, (United Kingdom, 2017), page 157.

[3] See MacEoin, Twilight Years, pages 776-777.

[4] Eunan O’Halpin, Defending Ireland: The Irish State and Its Enemies Since 1922, (New York, 2000 paperback edition), pages 200-201.

[5] Ibid, page 202.

[6][6] Donnacha Ó’Beacháin, Destiny of the Soldiers: Fianna Fáil, Irish Republicanism and the IRA, 1926-1973, (Dublin, 2010), pages 175-177.

[7] Wallace, The Fallen, pages 158-159.

[8] Wallace, The Fallen, page 166.

[9] Unknown author, Tom Harte and his comrades of the forties [commemorative booklet], (Dublin, 1990).

[10] Ó’Beacháin, Destiny of the Soldiers, page 178.

[11] I am deeply grateful to the insights of Lorcan Scott, Paddy McGrath’s grand-nephew, on the McGrath family’s revolutionary activities.

[12] Military Service Pension of Patrick Bernard McGrath, 2P122.

[13] Uinseann MacEoin, Survivors, (Dublin, (2nd edition)), page 49.

[14] Ibid, p.148.

[15] MacEoin, Twilight Years, page 777.

[16] Ó’Beacháin, Destiny of the Soldiers, page 166-167.

[17] O’Halpin, Defending Ireland, page 247.

[18] Kathleen Clarke, Revolutionary Woman, (Dublin, 2016 edition), page 308.

[19] Wallace, The Fallen, page 156.

[20] Ibid, page 162.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Ibid, pages 156-57.

[23] Ibid, page 162.

[24] Ibid , page 161.

[25] Ibid, pages 163-164.

[26] Clarke, Revolutionary Woman, page 309.

[27] Ó’Beacháin, Destiny of the Soldiers, page 178.

[28] Irish Workers Weekly, 31 August 1940.

[29] ‘McGrath and Harte Reprieve Committee’ (republican handbill), Jackie Clarke Collection, Ref No. 1/4/86/8

[30] Mac Eoin, Survivors, page

[31] Wallace, The Fallen, page 165.

[32] Mac Eoin, Survivors, page 124.

[33] O’Beacháin, Destiny of the Soldiers, page 178.

[34] The Irish Times, 5 September 1940.

[35] Transcript of Paddy McGrath’s letter, see ’50 Years Ago: IRA Convention and Six Reinterments’ (from Saoirse, September 1998 edition), see here: http://homepage.tinet.ie/~eirenua/sep98/50yrsago.htm (accessed online 20 January 2021).

[36] [36] Unknown author, Tom Harte and his comrades of the forties [commemorative booklet], (Dublin, 1990).

[37] Ó’Beachain, Destiny of the Soldiers, page 178.

[38] MacEoin, IRA in the Twilight Years, page 616.

[39] Ibid, page 670.

[40] ‘The reinterment of Paddy McGrath in 1948 – notes from Ruairí Ó’Bradaigh’ by Dieter Reinsich, see: http://www.ofrecklessnessandwater.com/blog/index.php/;focus=W4YPRD_com_cm4all_wdn_Flatpress_5487094&path=?x=entry:entry190513-191638 (accessed online 15 December 2020).

[41] MacEoin, Twilight Years, page 616.

[42] Ibid, page 670.

[43] Ibid, page 813.

[44] Clarke, Revolutionary Woman, page 309.

[45] Clarke, Revolutionary Woman, pages 311-12.

[46] Wallace, The Fallen, page 167.

[47] Ibid.

[48] ‘Remembering the Past: Execution of Paddy McGrath and Thomas Harte’ by Mícheál Mac Donncha, see https://www.anphoblacht.com/contents/27927 (accessed online 1 February 2021).

[49] Wallace, The Fallen, page 162.

[50] ‘Only one vengeance’ [Speech made by Brian O’Higgins at the re-interment of Patrick McGrath], n.d. 1948, National Library of Ireland, EPH B472.