‘An unnecessary number of graves?’ – The road to the Truce of July 1921

The triumphs and failures of diplomacy that led to the end of the Irish War of Independence. By John Dorney

Reflecting on the Truce declared between the British government and the insurgent Irish Republic on July 11 1921, senior civil servant Warren Fisher remarked, ‘better late than never, but I can’t get out of my mind the unnecessary number of graves’.[1]

To his mind, the bones of a political deal had been on the table for quite some time; direct talks with the Sinn Féin leadership based on an offer of ‘Dominion Home Rule’ – the same status for the south of Ireland as Canada or Australia. But stopping the killing and getting to talking had taken an unnecessarily long time, at some cost in lives.

Some of Fisher’s colleagues blamed the obduracy of their own side for the delay. One such, John Anderson, reflected that British policy had been based

‘on the assumption that we had to deal with a small minority of extremists engaged in a murder conspiracy for so-called political ends… [this] fond assumption, long known to be unfounded, has proved to be untenable’.[2]

A truce was agreed to end the Irish War of Independence in July 1921, but were ‘an unnecessary number of graves’ filled first?

But Andy Cope, the civil servant who had taken more personal risks than anyone to bring about the Truce, was also scathing of the Irish side and of the mythology of the War of Independence. When asked to give his version of events to the Irish Bureau of Military History in the 1950s he replied,

‘Over the years, I have had offers from various sources for my views and experiences but have turned all of them down because I regard the period (and also that following the Treaty) to be the most discreditable of your country’s history – it is preferable to forget it; to let sleeping dogs lie. ‘[3] ‘

It is not possible for this history to be truthful … The I.R.A. must be shown as national heroes and the British Forces as brutal oppressors. Accordingly, the Truce and Treaty Will have been brought about by the defeat of the British by the valour of small and ill-equipped groups of irregulars. And so on. What a travesty it will be and must be.’[4]

In his view, the IRA’s guerrilla war, as well as the response of the ‘militarists’ on his own side, had delayed, rather than brought about, a negotiated settlement.

This article is the story of how the Truce, in many ways a long delayed arrival at a destination mapped out well beforehand, was negotiated.

Background

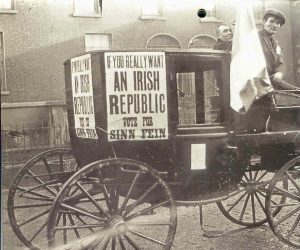

Sinn Féin had declared an independent Irish Republic after their victory in the General Election of December 1918 and in January 1919 declared that sovereignty rested in their own Parliament, the Dáil.

Sinn Féin had declared an independent Irish Republic after their victory in the General Election of December 1918 and in January 1919 declared that sovereignty rested in their own Parliament, the Dáil.

Initially the British government response had been to ignore the gesture, assuming that the republicans would come to their senses once, as Prime Minister Lloyd George remarked, they realised that they would not receive their salaries as MPs if they did not attend the Parliament at Westminster.

At first the British government did not take the self-declared Irish Republic seriously in 1919, then it resorted to coercion

The Prime Minister’s hope was that Irish aspirations could be walked backwards to the terms of the Government of Ireland Act, drafted in late 1919: Home Rule or limited autonomy, within the United Kingdom, for two separate parliaments, one in Dublin and one in Belfast.

But this strategy was to fatally underestimate the resolve of the Irish separatists. Over the following year and half, through a mixture of politics, mass mobilisation and guerrilla warfare, the Irish republicans took over much of the country’s administration and as good as neutered its police force the Royal Irish Constabulary, despite the Dáil and Sinn Féin being banned in late 1919.

When in April 1920 after a hunger strike and a general strike by the Labour movement, hundreds of republican prisoners interned up to the at point were freed, it was clear that British policy needed a rethink.

New blood in Dublin Castle, April 1920

Sir John French, the Lord Lieutenant, who had favoured a policy of military suppression in Ireland, was sidelined and a new Chief Secretary, Hamar Greenwood, appointed.

But beneath him, a team of top civil servants from Britain were imported to attempt to find a political solution. The head of the UK civil service, Warren Fisher, found the Dublin Castle administration to be, ‘woodenly stupid… it does not administer. It has never been any good and now it is quite obsolete.’[5]

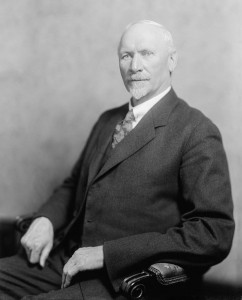

In their place, Fisher appointed as Under Secretary (head of the Irish civil service), John Anderson, formerly the chairman of the Board of Inland Revenue, with Mark Sturgis, previously Special Commissioner for Income Tax, as his Deputy. Thirdly, Alfred ‘Andy’ Cope a rising star in the Customs Department, was made assistant Under secretary. To Cope, was given the unenviable job of making secret, deniable-if-necessary, contacts with Sinn Féin and in particular with the charismatic political and military leader, Michael Collins.[6]

A new team of top civil servants was drafted into Dublin Castle in April to try to find a political solution.

A new military commander in chief, Nevil Macready, who had formerly worked as commander of the London Metropolitan Police, also arrived in Ireland in April 1920.

These men all thought the banning of the republican party Sinn Féin to be a mistake and recommended, even at this early stage, that the Government offer Dominion Home Rule to Ireland rather than trying to enforce the unpopular Government of Ireland Act. Even Macready, the general, was of the view that, ‘the situation has been allowed to drift into such an impasse that no coercion possibly remedy it’.[7]

Yet, in the short term, the new ‘doves’ in Dublin Castle lost the argument. David Lloyd George, though himself a Liberal, presided over a coalition government that was dominated by Conservatives, allies of the Ulster unionists and for the most part (with notable exceptions including Lord Curzon the Foreign Secretary) fierce opponents of independence for any part of Ireland.

He was also conscious that Conservatives blamed the previous Liberal Prime Minister, Asquith’s lenient treatment, as they saw it, of the Irish rebels of 1916 for the current unrest in that country. He therefore feared showing weakness and maintained ‘I will not break the coalition for Ireland’.[8]

As well as this, drowning out the aspirant peacemakers in the civil service, other, more hawkish voices in Ireland, especially the chief of police Henry Tudor and of the Imperial General Staff, Henry Wilson, urged the government to crush the insurgency before talking about a political settlement.

And so, the government policy in public remained that ‘no person should be permitted to hold communications with Sinn Féin except on the basis of the Government’s policy viz. the repression of crime and determination to carry through the Government of Ireland Bill’.[9]

In the late summer of 1920 it became clear what this would mean, with the passing of the Restoration of Order in Ireland Act, allowing for internment and execution of captured rebels, the replacement of inquest juries with military courts and the imposition in selected districts of martial law.

This was accompanied by the widespread deployment of newly recruited paramilitary police in the Black and Tans and Auxiliary Division, who, over the later summer and early autumn of 1920 unleashed a torrent of reprisals on both active republicans and civilians in towns and villages around the country.

Background talks

Yet at the same time as Lloyd George was saying in public that Crown forces now had ‘murder by the throat’ he was behind the scenes, attempting to make contact with Sinn Féin to negotiate an end to the violence.

It now seems clear that Andy Cope, on instruction from the government, was in contact with the separatists the whole time. In addition, from July 1920 onwards Lloyd George had put feelers out via intermediaries including Conservative MP George Cockerill and Irish businessman Patrick Moylett to Arthur Griffith, the acting head of the Irish Republic, about peace talks. Griffith indicated himself willingness to compromise, stating that in return for a ceasefire and the Dáil being allowed to meet openly, ‘an Irish Republic will not be mentioned’.[10]

Secret, indirect talks between the British government and the Irish insurgent began as early as July 1920.

These communications were not even sabotaged by the grave escalation of violence in Ireland in late 1920,in such events as the mass assassination of British intelligence officers in Dublin on Bloody Sunday on November 21. Lloyd George’s private response to the killing of British officers that morning was, not outrage, but rather to;

‘Ask Griffith for God’s sake to keep his head and not to break off the slender link that had been established. Tragic as events in Dublin were, they are of no importance. These men were soldiers and took a soldier’s risk’. [11]

All of which indicated that Lloyd George, while wanting to appear uncompromising in public, in fact wanted to settle the conflict in Ireland by negotiation as quickly as possible.

December 1920, a missed opportunity?

An intervention to mediate by Bishop Joseph Clune, of Perth, Australia, in November and December 1920, almost led to a ceasefire. The Bishop had extensive talks with the senior civil servants Anderson and Sturgis and, with the ubiquitous Andy Cope, met Michael Collins in secret. Cope also escorted the Bishop to Mountjoy Gaol to meet the now imprisoned Arthur Griffith, whose thoughts Clune would communicate to the Prime Minister.[12]

Griffith and Michael Collins apparently viewed the prospect of a ceasefire positively, with Collins voicing the opinion that ‘it could not possibly do us any harm’ and that the IRA ‘could not combat successfully England’s physical force if the directors of the latter get a free hand for ruthlessness’.[13]

There was some political disagreement at this stage, but both sides accepted that a deal would include Dominion status for Southern Ireland. At this point Lloyd George was not prepared to countenance giving an Irish state fiscal autonomy or independent armed forces.

An agreement was almost reached for a ceasefire in December 1920, but foundered on Lloyd George’s insistence that IRA arms be surrendered before any negotiations could start.

However the talks stalled, not so much on the political questions, as on the manner in which violence would be ended before real negotiations could begin. Collins and Griffith offered a bilateral ceasefire if the Dáil was allowed to meet freely.

Lloyd George, however, set out what were for the Irish unacceptable preconditions to peace talks. Not only would the IRA have to cease ‘murderous attacks on Crown forces’ but all arms, explosives and uniforms in their possession would have to be surrendered before talks could start in earnest. He also wanted to exclude Sinn Féin Members of Parliament, including Michael Collins and Richard Mulcahy, who were also senior IRA officers, from all negotiations.[14]

The response of Collins and Griffith was equally uncompromising. Griffith told Clune from prison that ‘there would be no surrender no matter what frightfulness is used’, while Collins told him ‘let Lloyd George make no mistake, the IRA is not broken’.[15]

They made a final offer to the British Government, via Clune, on December 28, 1920 of a truce, but with no surrender or IRA arms. Lloyd George appears to have been tempted and floated the offer in a meeting with his military and police chiefs in Ireland, Macready and Tudor, as well as Greenwood the chief secretary, but all of them rejected the idea out of hand and appealed for more time to break the insurgency. Macready, whose views seem to have hardened considerably between April and December of 1920, argued that ‘terror could be broken’ if martial law were extended across the whole country.[16]

Some cracks had appeared in Sinn Féin unity at this time; Galway County Council, one TD, Roger Sweetman from Wexford and the vice president of the party, the priest, Father Michael O’Flanagan had called publicly for an IRA ceasefire and the latter even mooted agreeing to partition, much to the displeasure of his party colleagues.[17]

This led to Greenwood in particular to suggest that with enough military pressure and the passing of Northern and Southern Ireland Parliaments into existence in June 1921, the ‘moderates’ in the separatist movement could be isolated from the ‘extremists’ and would accept the Government’s solution to the conflict. Thus, ‘there was no need to hurry a settlement’ and in the meantime ‘coercion is the only policy’.[18]

The result though was six more bloody months, in which well over a thousand more people would die in political violence in Ireland. Mark Sturgis, part of the civil service team who, throughout, attempted to get peace negotiations back on track remarked, ‘it really is like a nightmare isn’t it? One cannot possibly see that there is any material thing at all between us if only this fencing for position could stop and we could get around a table’.[19]

Clandestine contacts

Andy Cope seems to have been in constant clandestine contact with Michael Collins throughout early 1921. IRA member Laurence Nugent, for instance, recalled that Cope met Collins in rooms on Dublin’s Abbey Street and wondered why he met Collins alone rather than Eamon de Valera, the President of the insurgent Republic, or Minister for Defence Cathal Brugha. [20]

Cope came in for some fierce criticism from his own side for these contacts, even being accused in some circles of betraying secrets to the IRA. General Macready, who did not make such allegations, nevertheless thought that,

‘he has not a large enough mind and no idea of the dignity of Empire. I am quite prepared to swallow a good deal…in order that no obstacle be placed in the way of a possible agreement, but there is a limit and I do not think poor Andy Cope is mentally capable of seeing when that limit is reached’.[21]

British civil servants, especially Andy Cope kept secret peace talks alive alive in early 1921 but were continually frustrated by the ‘militarism’ on both sides.

Cope, Sturgis and James McMahon (another under-secretary who tried to use his contacts with the Catholic hierarchy to instigate peace talks) continued to try to arrange a ceasefire in the spring of 1921. [22] Under their auspices, Eamon de Valera, returned from America in late 1920 and whom Lloyd George seems to have as a potential ‘moderate’, held meetings with Northern Unionist leader James Craig and Conservative politician Edward Stanley, Lord Derby, in April, 1921. Lord Derby floated the prospect of Dominion Home Rule, including fiscal independence. De Valera was interested, but wanted to meet directly with Lloyd George ‘without preconditions’[23]

The Dublin Castle ‘peace party’ of Anderson, Sturgis and Cope were sure that a deal was in prospect by early May and were thus dismayed by the ongoing, indeed intensifying, IRA campaign. Sturgis, for instance reacted to the IRA’s destruction of the Custom House in Dublin on May 25 with dismay. How could this happen, he wondered, ‘in spite of negotiations?’ ‘How can this make settlement anything but more difficult?’.[24]

The failure of coercion

Lloyd George had committed from late December 1920 to a policy of coercion, that in tandem with elections to the two new Home Rule Parliaments in Dublin and Belfast by May 1921, would undermine support for the republican ‘extremists’. His military and police advisors had assured him that by that time they would have broken the back of the IRA insurgency.

He was still persisting with this line by May 12, when the cabinet voted 9 votes to 5 against offering a truce to the Irish republicans.

However, neither of these twin strategies bore fruit. In the elections to the Southern Ireland Parliament, Sinn Féin had won all of the seats unopposed on May 24.[25] If the Government of Ireland Bill could not be made to work, then ‘Southern Ireland’ would become a ‘Crown Colony’ under martial law, by July. Or in other words, Ireland would have to be explicitly ruled by force, without any democratic legitimation.

By June 1921 it was clear that the twin policies of granting Home Rule while coercing the insurgent republicans was a failure.

Furthermore, police and military casualties in Ireland, as well as the number of ‘outrages’ continued to rise through the early summer of 1921, despite the influx of reinforcements that brought Crown forces’ numbers up to over 80,000 by June.[26]

By now the military advice to the government had lost its optimistic tone. One general, Wimberly, thought that ‘really brutal methods’ such as employed in the Scottish Highlands after the Jacobite rebellion of 1745 might work, but they ‘would never be tolerated by the British public in 1921.’[27]

Winston Churchill, the Secretary of State for the Colonies noted that due to the conflict in Ireland, ‘we are getting an odious reputation’ internationally.[28]

General Macready, the Army Commander in Chief in Ireland, by now apparently disabused of the notion of a military solution, that he had advocated the previous December, wrote in June 1921 that

‘there are of course one or two wild people about who still hold the absurd idea that if you go on killing long enough peace will ensue. I do not believe it for a moment, but I do believe that the more people are killed, the more difficult will be the final solution’.[29]

By early July it was clearly time to talk peace, as Lloyd George finally acknowledged. But how to choreograph the end of hostilities?

The path to the Truce

Perhaps the decisive intervention in the end was by South African statesman Jan Smuts, who was approached by the Irish to mediate in May. Smuts had served as a British general in the First World War and in the Imperial War cabinet, but back in the Boer War of 1899-1902 had fought as a guerrilla against the British, much as the Irish republicans now did, and thus had an insight into both sides.

Smuts urged negotiation on both the Irish Republicans and on the British, to whom he pointed out that with a Northern Ireland Parliament up and running from June 22, northern unionist opposition to Irish self-government was no longer a factor and it was now possible ‘to deal on statesmanlike lines with the rest of Ireland’. [30]

It was he and Lloyd George who jointly drafted a conciliatory speech made by King George V at the opening of the Northern Ireland Parliament, which expressed the hope that ‘today may prove to be the first step towards an end of strife’.

While, contrary to some accounts, this was in the nature of a public signal rather than a diplomatic initiative on the part of the King himself, it also opened the door to the final negotiations for an end to hostilities.

Perhaps the decisive intervention in the achievement of the Truce was by South African statesman Jan Smuts

Just two days later, Lloyd George formally invited Eamon de Valera to London for peace talks. But first there had to be an end to fighting.

It was again Smuts, along with southern unionist leader, Lord Middleton, who brokered the formal truce. The British had some misgivings about bestowing the status of a legitimate army on the IRA and of equal negotiating partners on Sinn Féin, but were also anxious by now to terminate the troublesome conflict. As Churchill commented, ‘I would go a long way to humour them’.

The truce was formally agreed following negotiations between general Macready, Eamon de Valera , Cathal Brugha, Robert Barton and Eamon Duggan in Dublin’s Mansion House on July 8. Both sides agreed to an end to armed attacks, arrests, destruction of property and ‘provocative displays’, to come into effect on midday on July 11. There was however to be no release of prisoners, nor evacuation of Crown forces.[31]

The Truce did not end violence overnight. Indeed in the North, where loyalists feared a sellout of their position, as Belfast IRA officer Roger McCorley acidly remarked, ‘the Truce lasted six hours only’.[32] In fact the day before the Truce came into effect was nicknamed ‘Belfast’s Bloody Sunday’ such was the violence there. But in most Ireland fighting did cease and the way was open for negotiations.

From Truce to Treaty

Those negotiations ultimately led to the Anglo-Irish Treaty, signed in December 6, 1921 in London. The Treaty, was in many ways the realisation of an end point that had been flagged well in advance.

The partition of Ireland was confirmed, though subject to Boundary Commission, which would determine the exact size of the Northern state. The southern state would be a self governing Dominion of the British Empire – not a Republic – but would have full fiscal powers, its own armed forces and police.

From the point of view of such men as Mark Sturgis, John Anderson and particularly Andy Cope, this had been an outcome they had identified as inevitable as early as April 1920, which in their view, rendered all of the violence in between the unnecessary product of ‘militarism’ on both sides.

On the other hand, there can be no argument that, however unpalatable, the IRA’s guerrilla war extracted far greater concessions from Lloyd George’s government than he had wanted to grant.

Andy Cope paid a high personal price for his role as secret intermediary between the British government and Michael Collins, being accused by some on his own side of ‘treachery’.

Eamon de Valera after initial talks with Lloyd George, had not taken part in the negotiations directly, sending Collins and Griffith in his stead. But he famously refused to endorse the deal they had signed. So too did much of the IRA, sparking another, internecine, conflict in Ireland in 1922-23.

Andy Cope, was given the job, after the Treaty was ratified, of overseeing the transfer of power to the new Irish government during the Civil War, a period he afterwards described as, ‘the most discreditable of your country’s history’.

Cope himself paid a heavy personal cost for his efforts at peacemaking in 1920-21. In 1924, he was accused in the House of Lords by Lord Muskerry of having passed information to Sinn Féin, ‘with the result that these plans devised by His Majesty’s officers came to naught and in many cases His Majesty’s officers and men lost their lives. The result of this treachery at headquarters was to paralyse the efforts of His Majesty’s officials’. [33]

John Anderson retorted that ‘Cope had done nothing without his knowledge and consent and upon the orders of government’ , but a cloud nevertheless hung over his reputation for many years.[34]

In later years he ‘found religion’ and put his experiences in Ireland in this perspective. Concluding his reply to the Bureau of Military History he wrote, ‘Ireland has too many histories; she deserves a rest. Her present need is a missioner to teach her that Love, not Hate, is still the only password both to Earthly Happiness and the Heavenly Kingdom.’ [35]

However, his role and those of his colleagues who helped to bring about the Truce of 1921, deserves to be recognised today.

References

[1] Michael Hopkinson, in, Joost Augustine, ed., The Irish Revolution, 1913-1923, (Palgrave, London, 2002) p.124

[2] Ibid. P.126

[3] Andy Cope BMH response online here. Letter dated January 3, 1951.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Michael Hopkinson, The Irish War of Independence, Gill & MacMillan, Dublin 2004, p.59

[6] Ibid, p.60-61, See also Frank Packenham, Peace by Ordeal, The Negotiation of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, 1921, Sidgwick & Jackson, London, 1972, p. 67 who quotes another civil servant as saying, Cope is now known to have been carrying out sub-rosa negotiations with the Sinn Féin leaders’.

[7] Hopkinson, War of Independence, p.61

[8] Ibid. P.62

[9] Padraig O Ruairc, Truce, Murder, Myth and The Last Days of the Irish War of Independence, Mercier, Cork, 2016, p.20

[10] Ibid. P.22

[11] Joseph Connell, The Shadow War, Michael Collins and the Politics of Violence, Eastwood Books, 2019, p.240

[12] Hopkinson, War of Independence, p.183

[13] O Ruairc Truce p.31

[14] Ibid. P.32

[15] Ibid. P.34

[16] Charles Townsend, the Republic, The Fight for Irish Independence, Penguin, London, 2013, p.223-224

[17] O Ruairc Truce,, p.26-28.

[18] Hopkinson, War of Independence, p.183, 187

[19] Ibid. P.188

[20] Laurence Nugent BMH WS 907.

[21] Hopkinson, War of Independence p.196

[22] Townsend the Republic, p. 305-306

[23] Hopkinson, War of Independence, p.189

[24] Townsend, The Republic, p.306

[25] Sinn Fein won 128 seats unopposed, all of them except for four unionist elected for Trinity College Dublin, who were also unopposed. For the results see https://electionsireland.org/results/general/02dail.cfm. Together with the concurrent elections to Northern Ireland’s new parliament this was taken by the republicans to be elections to the Second Dail.

[26] O Ruairc, Truce, p.51

[27] Ibid, p.53

[28] Ibid. P.46

[29] Hopkinson, War of Independence p.193,

[30] Ibid. P193

[31] Townshend p.307-309

[32] Robert Lynch, The Northern IRA and the Early Years of Partition, Irish Academic Press, Dublin 2006, p.80

[33] Hansard, March 5 1924, https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/lords/1924/mar/05/claims-of-irish-loyalists

[34]Alfred Cope Entry, Dictionary of Irish Biography, https://www.dib.ie/biography/cope-sir-alfred-william-andy-a2028

[35] Cope BMH letter

See also, John Dorney speaking on this topic for Fingal Festival of History here: