Forgotten Charity Between Ireland and America, 1889 and 1921

By Mark Holan

Media on both sides of the Atlantic rushed to report the story that connected Black ‘47 to COVID-19. When Navajo Nation and Hopi Reservation communities in the western United States were hard hit by the virus, the Irish people answered their cry for help with an estimated $3 million (€2.5 million).[1] The relief was framed as a reciprocal gesture for $170 the Choctaw Nation donated to starving Irish families during the Great Famine.

These are hardly the first or only examples of charity between Ireland and America. But this year marks the 100th anniversary of the American Committee for Relief in Ireland, a humanitarian and nationalist effort that began months before the Truce and extended a year beyond the Treaty.

In particular, the people of Johnstown and surrounding Cambria County in Pennsylvania sent money to ease war-related suffering in Ireland “as a token of gratitude” for aid the community received 32 years earlier from Ireland, when the raging waters of a broken dam killed 2,209 people, including Irish immigrants, in an infamous flood.

The 1889 and 1921 relief measures, respectively heralded in their day as both symbolic and practical, have never received the same attention as the 1847 and 2020 charity. Here’s a look.

The Johnstown flood 1889

Agrarian activist Michael Davitt helped prompt the 1889 donation. While America and other wealthy nations surely would provide aid to the flooded town’s survivors and rebuilding efforts, “this is no reason why we should not at once send some small token of our appreciation of the terrible suffering we read of, and in remembrance of the many donations that have reached this country from Pennsylvania,” he wrote in the Freeman’s Journal.

Short of sending such “practical evidence of Ireland’s sympathy with American sufferers,” Davitt suggested, “it would be more decent of us to keep our speeches and resolutions to ourselves.”[2]

Davitt knew the hills, valleys, and towns of Pennsylvania better than most people in Ireland. His parents and three sisters had settled in Scranton and Philadelphia. He made several U.S. visits before 1889, including an 1880 stop in Pittsburgh, 70 miles west of Johnstown, on behalf of the National Land League. Davitt likely rolled through Johnstown on the state’s extensive railroad network, built largely by Irish immigrant labor.

In 1889 nearly $5000 was raised in Ireland for the victims of disastrous flood in Johnstown Pennsylvania

Davitt likely saw relief to Johnstown not only in humanitarian terms, but also as a debt of honor for the hundreds of thousands of dollars Americans had sent to the Land League. By June 1889, the effort he began a decade earlier with Charles Stewart Parnell faced the challenges of continued coercion from the British government and a papal encyclical against agrarian outrage.

Davitt became embroiled in the Parnell Commission hearings in London and also entangled in the politics and personalities surrounding the murder of Dr. Patrick Henry Cronin – a leader of Clan na Gael assassinated by members of rival faction within the Fenian group – a month earlier in Chicago. Davitt’s diary for the period does not mention the flood.[3]

Within days of Davitt’s letter and less than two weeks after the Johnstown flood, Dublin Lord Mayor Thomas Sexton opened an account at Hibernia Bank, College Green, and ordered £1,000 cabeled to the governor of Pennsylvania, a move supported by Dublin Corporation. Sexton subscribed £50. Davitt donated £25 on behalf of his Irish Woolen Manufacturers and Export Company, and £5 personally. Cantrell & Cochrane gave £100, matched by A. Guinness and Co.[4]

“Ireland has not forgotten the assistance she has received from this country in the past, and now, although poor herself, comes forward with five thousand dollars to aid the sufferers in the Conemaugh Valley”.

Catholic Archbishop of Dublin William Walsh also contributed £100. In a letter to Freeman’s Journal, he declared receiving “a much larger amount” from “a generous benefactor” in America to be expended at his own discretion. “I have no difficulty in finding a suitable field at home for the expenditure of what has been sent to me,” he wrote. “But I gladly avail myself to the opportunity” to apply “a substantial portion” to Pennsylvania relief. Later that year, in one of the first books about the flood, a U.S. journalist reported Walsh donated $500.[5] (All currency and amounts cited here as reported in period sources.)

Other collections were taken around Ireland. Within three weeks of the disaster, a newspaper in Harrisburg, the Pennsylvania state capital, published a donor list released by the governor that showed $4,861 from Ireland.[6]

“Ireland has not forgotten the assistance she has received from this country in the past, and now, although poor herself, comes forward with five thousand dollars to aid the sufferers in the Conemaugh Valley,” another Pennsylvania paper editorialized. “When it is taken into consideration that Ireland has so many poor within her own borders, this gift is princely.”[7]

But Ireland’s quick response cost it historical credit. Two key reports on financial relief to Johnston, both published in 1890, do not mention the country’s contribution.[8] Donations from England, Canada, Australia, and Germany are recorded.

Soon after the Johnstown donation, Irish attention turned to a tragedy within its own shores. The Armagh rail disaster of June 12 killed 80 and injured more than 250 others on a school excursion.

Aid to Ireland 1921

As Johnstown’s slow recovery extended into the new century, the land reform and Home Rule movements once led by Davitt and Parnell gave way to a new generation of more radical aims and more militant methods in Ireland. By 1919 this had evolved into the Irish War of Independence. Escalating violence caused widespread suffering.

The burning of Cork city in December 1920 prompted creation of the American Committee for Relief in Ireland to supply humanitarian aid and keep public pressure on the British and U.S. governments.

The American campaign was officially launched on St. Patrick’s Day 1921, but contributions began flowing earlier. The Archdioceses of New York sent over $100,000.

Johnstown and Cambria County, mindful of the charity from Ireland three decades earlier, sent £2,500 “as a token of its gratitude for help rendered to it by Ireland in 1889, when it suffered heavily through a disastrous flood,” the Irish White Cross said in a 1922 report.[9]

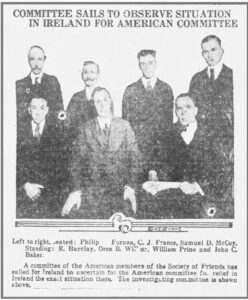

In 1921, Irish Americans raised hundreds of thousands of dollars for relief in Ireland during the War of Independence

The Pennsylvania money was specifically allocated to the Bishop (later Cardinal) Joseph MacRory’s Belfast Expelled Workers Fund. White Cross Treasurer James S. Douglas acknowledged the donation in a cable to Irish newspapers. He attributed the 1889 Johnstown relief to donors in Dublin, Belfast, Cork, and Clonmel.[10]

A “list for American subscriptions other than those of the American Committee for the Relief in Ireland” in the Douglas papers at the National Library of Ireland shows a £4,113 donation from the Catholic Dioceses of Altoona, which includes Johnstown.[11] The Pittsburgh Catholic newspaper reported that Johnstown sent $10,000, with “at least $25,000 more” expected from diocesan churches and “several non-Catholics.” The same story claimed 1889 Irish relief to Johnstown totaled $16,633.[12]

Johnstown and Cambria County, mindful of the charity from Ireland three decades earlier, sent £2,500 “as a token of its gratitude for help rendered to it by Ireland in 1889, when it suffered heavily through a disastrous flood

The Catholic also reported that Thomas P. Cahill, “a stalwart friend of Irish freedom,” initiated the relief from Johnstown. He was further described as the son of James Cahill, one of the Fenian rescuers in the 1867 Manchester martyrs episode.

In 1921, Pennsylvania was America’s second most populous state with the third highest number of Irish immigrants, nearly 122,000. But the state’s $211,000 subscription to the Relief in Ireland campaign ranked seventh nationwide and was less than half Pennsylvania’s $541,000 subscription to the Irish bond drive a year earlier.

Nevertheless, in November 1921 Douglas visited Pittsburgh on the first stop of a tour to thank Americans for their collective $5 million in relief. “I addressed the gathering, conveyed the thanks of the White Cross and the Irish people for what they had done and explaining the manner in which the White Cross had administered the relief made possible by the American Committee’s funds,” he reported.[13]

The Choctaw’s 1847 generosity to Ireland was recognized by a plaque at Mansion House, Dublin, and a sculpture in County Cork, years before the headlines of Irish pandemic relief to America. The Johnstown Flood Museum and other local history societies and libraries in the Pennsylvania community said they do not have any records of Ireland’s “princely gift” in 1889.

Mark Holan writes about Irish history and contemporary issues at markholan.org. Mark Holan © 2021

[1] “Irish people donate €2.5m to Native American tribe devastated by coronavirus” The Irish Times, Nov. 20, 2020.

[2] “The Awful Calamity In Pennsylvania” Freeman’s Journal, June 6, 1889.

[3] Per Aug. 24, 2021, review of TCD MSS 9549-9552 by TCD’s Felicity O’Mahony.

[4] “The Dublin Corporation and the Johnstown Disaster”, Freeman’s Journal, June 10, 1889, and “Mansion House American Relief Fund,” FJ, June 12, 1889.

[5] Johnson, Willis Fletcher, History of the Johnstown Flood, Edgewood Publishing Co., Philadelphia, 1889, p. 287.

[6] “The Golden Stream”, Harrisburg Telegraph, June 17, 1889.

[7] Editorial, The Daily News (Lebanon, Pa.), June 17, 1889.

[8] Report of Johnstown Flood Finance Committee, G.T. Swank, Johnstown, 1890, and Report of Citizens Relief Committee of Pittsburgh, Myers, Shinkle & Co., Pittsburgh, 1890.

[9] Irish White Cross Report, 1922, p. 21

[10] “Irish White Cross”, Freeman’s Journal, April 29, 1921, and “Generous American Gift,” Irish Independent, April 29, 1921.

[11] “Copy list for American subscriptions other than those of the American Committee for the Relief in Ireland”, Undated. In Senator James Green Douglas Papers, National Library of Ireland.

[12] “The Aid Extended To Irish To Survivors Of Johnstown Flood”, The Pittsburgh Catholic, May 5, 1921.

[13] “Account by James Green Douglas of his visit to America to explain how the Irish White Cross was administered.” Undated. In Senator James Green Douglas Papers, National Library of Ireland.