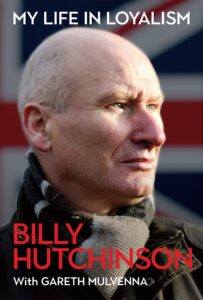

Book Review: My Life in Loyalism

By Billy Hutchinson and Garreth Mulvenna

By Billy Hutchinson and Garreth Mulvenna

Published by Merrion Press 2020

Reviewer: Daniel Murray

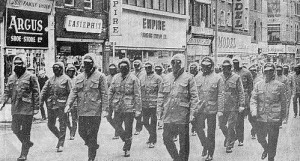

Like many a young man in Northern Ireland in the early 1970s, Billy Hutchinson began his political journey as a rioter in his home city of Belfast, slugging it out with missiles behind makeshift barricades against the teargas and batons of the authorities.

The highlight of Hutchinson’s street-fighting exploits was during the assault on ‘Fort Milanda’, an old Milanda bakery building on Snugville Street where the King’s Own Royal Regiment had set up base, right in the heart of a community with which it was increasingly at odds.

This book is an autobiography of loyalist paramilitary Billy Hutchinson, co-written by historian Gareth Mulvenna

Such feelings were vented on the last week of September 1970, when hundreds of local residents, mostly youths, surrounded ‘Fort Milanda’, hurling anything at hand and eventually using a large post to ram down the gates. Espying a chance to make a name for himself, as well as express what he thought of the whole situation in his homeland, Hutchinson clambered up a drainpipe and snatched the regimental flag of the King’s Own from where it fluttered.

With the enemy’s disgrace complete, Hutchinson climbed back down to the cheers of his onlookers but, for him, the battle had been for more than its own sake:

It might be called ‘recreational rioting’ nowadays, but in 1970 we saw ourselves as street soldiers of a kind. This wasn’t just thuggery or troublemaking. We were defenders of the community.

He was 14 years-old; on the surface, just another young man in Doc Marten boots and a Wrangler jacket like many others in the UK but coming of age in a very different part of it. Resistance brought the respect of his peers and elders but also the less impressed attention of the British state, which harassed, arrested and eventually imprisoned him. All of which would make him a worthy subject of a Christy Moore song – except the Shankill born-and-bred Hutchinson was a member of the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF), fighting to keep Northern Ireland British.

Hutchinson cut his teeth rioting on the streets of his native Shankill Road against the British Army in the early 1970s

Hutchinson is not oblivious to the contradiction of his actions: “People might wonder why we, as Loyalists, were attacking the army of a state we professed an allegiance to.” If his reader is thinking ‘good question’, then “the answer is simple: The army was being heavy-handed with young men on Shankill, and we saw them as an obstacle to getting our hands on the republicans while the authorities dithered.”

The definition of ‘republican’ could be open for debate. The double murder of Michael Loughran and Edward Morgan in October 1974 was due to the pair being identified by Loyalist intelligence “as active republicans. How accurate the information was, I don’t know.”

Hutchinson is rather coy about his own activity, describing in his book little more than how the “evidence was clearly pointing toward my involvement in the shooting” when the police brought him in for questioning. Notably, he refers to the two deaths as assassinations, suggesting that, whatever the rights and wrongs, truth or untruth, of five decades past, he remains untroubled by the deed.

Hutchinson is rather coy about his involvement in the double murder of two Catholics in 1974, for which he was convicted and served 16 years in prison.

The criminal justice system was not quite so sanguine, sentencing Hutchinson to prison and there he stayed for the next sixteen years until his release in 1990. In a sign of how the times were changing, Hutchinson worked, as director of the Springfield Inter-Community Development Project, alongside Tommy Gorman, a fellow ex-prisoner, except for the other side – not that it stopped the UVF officer and Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA) member from striking up a bond, as well as a mode of operation, each running programmes in their different communities, and then meeting up to compare notes.

The two had something else in common: both had grown sceptical of the people who previously held all the answers. Hutchinson witnessed Gorman openly needling Gerry Adams, telling him that if achieving a United Ireland was simply a case of Nationalists outbreeding Unionists, like Adams was proposing, then why did Gorman have to spend so much time in jail? As for Hutchinson, he had the last word with Ian Paisley when the preacher refused to enter a lift with “a UVF murderer.”

Hutchinson retorted that such niceties did not bother Paisley when he was urging others to their deaths:

As the doors to the lift slowly closed, Paisley’s face dropped and for once he was speechless – here was a man who had led the loyalist people to heartache and death, and still, thirty years later, he hadn’t changed his tune. He was a total hypocrite.

His dealings with David Trimble went better, if only because their two Unionists parties needed each other in the Peace Process to which both were committed. Otherwise, Trimble dismissed Hutchinson, the Shankill native, for his lack of formal education. “It didn’t annoy me,” Hutchinson claims:

It was pure ignorance. It was just a ploy to make people think that they had to vote for doctors and lawyers, like they had always done.

This relationship of a mutual goal running parallel with general contempt reflected the wider one between white-collar Unionists and their roughneck cousins.

The former needs the latter for votes on election day, before abandoning them to the ghettos the next, leaving the working-class, as Hutchinson describes, “like a dog that is kicked by its owner and keeps coming back to get fed.”

It’s this sort of insight that stands Hutchinson out from the other poster boys of Loyalism, the musclebound Johnny Adair and viperish Billy Wright, both of whom Hutchinson knew, and neither of whom he could stand.

It is curious that on the few occasions Irish Republicans appear in Hutchinson’s narrative, he seems to get on reasonably well with them, whereas his relations with fellow loyalists are often fraught.

A curious note, then, that while Hutchinson joined the UVF to protect Northern Ireland from the horrors of Fenianism, on the few occasions Irish Republicans appear in his narrative, he seems to get on reasonably well with them.

With people sharing the same Unionist cause, however, it is just one thing after another. One wonders if the likes of Gorman could tell a similar story: his sparring with Adams ended with Gorman self-exiled to Donegal to escape the harassment of his former allies, who had driven him to distraction with fire engines and food takeaways falsely sent to his door.

Hutchinson’s internecine issues were less childish and potentially more deadly, such as when the Ulster Defence Association (UDA) threw a pipe-bomb at Hutchinson’s house in 2000. As the windows were of reinforced glass – in addition to the steel doors, security cameras and alarms – the weapon bounced off harmlessly.

UVF and UDA combatants bombed or shot up offices connected to the other, while family members were considered fair game, even if shared across the divide. “One guy who was in the UDA, and whose brothers were in the UVF, put his own mother out of the Shankill” as part of the “purge against UVF-linked families.” A kicked dog can still bite, particularly, it seems, other dogs.

Hutchinson was a significant party to the 1990s peace process and served as a member of the Legislative Assembly.

Hutchinson was by then a Member of the Legislative Assembly (MLA), but even an elected representative could not ignore the street law of the Shankhill. “Sometimes you face intracommunal issues that can’t be solved in the parliamentary chamber,” as he puts it. Hutchinson had demonstrated the implacable truth of that as far back as 1972, when he pulled out a gun at a UVF gathering to rebut a proposal not to his liking. The matter was dropped.

Another UVF rival of Hutchinson’s at the time, Ken Gibson, stood as a candidate in West Belfast during the 1974 UK General Election, hoping to take working-class Unionism in the same political direction that Hutchinson would espouse decades later. Hutchinson does not spare Gibson the humiliation of informing his readers of how bad a drubbing the would-be politico got: 0.4% of the vote.

Gibson would later condemn the Unionist politicians of 1974 – the ones who actually succeeded in being elected – as ‘back-stabbers’, an incongruity that gave Hutchinson a dry chuckle when he read it in the newspaper. He prided himself on hearing “the mood music, while Ken Gibson was trying to play an unpopular tune.”

But tunes can be changed, as Hutchinson and even the “total hypocrite” Paisley would do when the latter stood alongside Martin McGuinness as the First and Deputy First Ministers of a new Northern Ireland – or maybe an old Northern Ireland in new clothes. The difference, then, between a warmonger and peacemaker is perhaps as simple as a single thing: Timing.