‘The Blood of Irish rebels flowed in his veins’: Che Guevara and the Irish

By Barry Sheppard

Since his execution in Bolivia in 1967, Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara has been an ever-present icon of left protest movements and anti-imperialist struggles throughout the world. In Ireland, particularly Northern Ireland, Guevara has, over the years become associated with Irish republicanism, primarily due to his status as world-famous revolutionary.

He had, however, other familial connections with Ireland, which for some, further solidified any ideological associations.

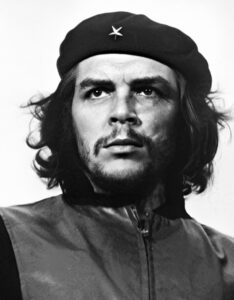

Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara, became an enduring symbol of the revolutionary left. His ancestors left Ireland for Argentina in 1749

Guevara was a descendent of Galway native, Patrick Lynch, born in 1715, and who in the aftermath of land confiscations in Ireland was said to have made his way to Buenos Aires in 1749 via Bilbao. Guevara’s Irish roots are these days arguably well-known and his Irish heritage is now an accepted fact. However, it has not always been the case.

To get a sense of how the famous revolutionary’s Irish heritage has ebbed and flowed over the years, this article examines how he was represented in mainstream Irish newspapers from the time he first came to international attention as a shadowy and curious figure in the Cuban revolution, to recent times in controversies over efforts to memorialise him in Irish society.

Ernesto Guevara, man and myth

Guevara was the eldest of five children in a middle-class family who had progressive leanings. His father, Ernesto Guevara Lynch had met his mother, Celia de la Serna in 1927. Both branches of the family were well-to-do, but had come down in the world by the time the first born had arrived.[1]

Guevara was the eldest of five children in a middle-class family who had progressive leanings. His father, Ernesto Guevara Lynch had met his mother, Celia de la Serna in 1927. Both branches of the family were well-to-do, but had come down in the world by the time the first born had arrived.[1]

Ernesto Guevara led a life of semi-comfort, although dogged by asthma which would hamper him throughout his life. Nevertheless, he excelled at sports (particularly rugby), and in his academic studies, going to medical school, eventually graduating in 1953.

It was, however, his 1951-1952 journey through South America with his friend Alberto Granado, where he witnessed the poverty of indigenous communities which would be his political awakening. In 1953 he travelled to Guatemala, where he witnessed the CIA-supported overthrow of Jacobo Arbenz’s progressive government. Another formative moment in his life, it helped solidify his political outlook and led him to Mexico where he met the exiled Castro and his supporters who were preparing for revolution in Cuba.

The success of the Cuban revolution at the dawn of 1959 propelled the main figures, the Castro brothers, Fidel and Raul, as well as the Argentinean Guevara to worldwide attention

The success of the Cuban revolution at the dawn of 1959 propelled the main figures, the Castro brothers, Fidel and Raul, as well as the Argentinean Guevara (the only foreign national in Castro’s small band of revolutionaries) to worldwide attention. Guevara was stationed for a number of months at La Cabaña prison, where he oversaw the executions of those who were deemed to be enemies of the revolution, before president of the National Bank of Cuba. Leaving Cuba in 1965, Guevara sought to export the revolution, fighting for a time in the Congo before returning to South America and his ill-fated excursions into Bolivia, where he was captured and executed in October 1967.

Guevara’s ‘afterlife’ as an icon of the international left is a fascinating topic itself, growing exponentially in the years after his death. Professor of Latin American Studies, Marc Becker states in the introduction to the 1998 edition of Guevara’s Guerrilla Warfare:

‘Thirty years after his death, university students throughout Latin America still wear T-shirts emblazoned with Che Guevara’s image. Workers carry placards and banners featuring him as they march through the streets demanding higher wages and better working conditions. Zapatista guerrillas in southern Mexico paint murals depicting Che together with Emiliano Zapata and Indian heroes’.[2]

The image of the Argentinean hero of the Cuban revolution has, as Becker notes, been a mainstay of revolutionary imagery throughout vast swathes of the world. This also includes the island of Ireland, where Guevara’s image has particular resonance due to one artist in particular.

The famous image of Guevara, taken from the 1960 photograph Guerrillero Heroico, by photographer of the revolution, Alberto Korda,[3] found new life when adapted for print by Irish artist Jim Fitzpatrick. Fitzpatrick’s print is easily one of the world’s most recognisable and reproduced pieces of popular art of the late twentieth century.

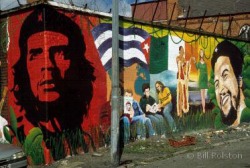

Guevara’s steely image, while associated with international student radicalism and worker movements has also adorned countless gable walls in northern nationalist areas during the prolonged conflict from the 1960s onwards.

Irish Professor of Sociology, Bill Rolston in his hugely popular examination of political murals in Ulster, notes the inclusion of Guevara murals in republican areas, stating they were representative of other struggles which ‘struck a deep resonance with Irish republicans’.[4] While perhaps a less-potent image now, than it was two decades ago, Guevara’s image retains much power to elicit emotive responses among left and right.

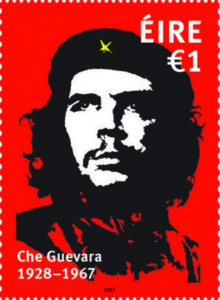

A case in point was the recent decision by the Irish postal service An Post to mark the fiftieth anniversary of Guevara’s death at the hands of Bolivian forces with a commemorative stamp. The ensuing controversy, aided by international pressure and from those on the Irish right, not only led to the stamp selling out in record time, but threw new focus onto Guevara’s legacy among Irish people, given the famous revolutionary’s part-Irish ancestry.

‘The first thing to note is that in my son’s veins flowed the blood of the Irish rebels, the Spanish conquistadores and the Argentinean patriots’. Ernesto Guevara Lynch

The fallout of the postal stamp issue, and a proposed 2012 permanent memorial to Guevara in Galway,[5] led to much debate on traditional and social media about Guevara’s Irish roots, with articles such as ‘Rebel Blood: Che’s Irish Heritage’ and YouTube videos such as ‘Che Guevara, Irish Hero’?, stimulating debate.

A turning point in awareness of Guevara’s Irish heritage undoubtedly came via an interview with his father in 1969. Ernesto Guevara Lynch, a man who Guevara biographer, Jon Lee Anderson notes had an ‘Irish temper’,[6] and who it was said ‘embraced his Gaelic heritage’[7] gave an important interview which is still partly quoted to this day.

‘The first thing to note is that in my son’s veins flowed the blood of the Irish rebels, the Spanish conquistadores and the Argentinean patriots. Evidently Che inherited some of the features of our restless ancestors. There was something in his nature which drew him to distant wanderings, dangerous adventures and new ideas’.[8]

Guevara Lynch’s quote is, more often than not, edited down to the much more marketable, ‘in my son’s veins flowed the blood of the Irish rebels’, adorning t-shirts alongside depictions of figures from Ireland’s revolutionary past (as well as accompanying the aforementioned stamp).

The reference to the Spanish conquistadores is, perhaps, less compatible with the popular image of Che as an anti-imperialist icon. Regardless, the part-quote from Guevara Sr. has perhaps done more to solidify his son’s Irishness than a team of seasoned genealogists ever could.

Irish reaction to the Cuban revolution

It begs the question, however, at what point did Ireland become aware of Guevara’s ‘Irishness’? Certainly, in the early days, when the Cuban revolution made world headlines, there was no clue. How could there have been? Press agency reports which prominent Irish newspapers such as the Irish Independent reproduced, singled out Guevara as a figure of note, albeit one that was shrouded in mystery.

Noting a state of euphoria at Fulgencio Batista’s overthrow at the hands of the young radicals, it was exciting copy for readers, with figures like Guevara and the Castro brothers fast becoming household names.

Reports on revolutionary euphoria came with notes of caution, however. While the victors were ‘Conservative men’ by European standards, there was a ‘question mark on Guevara, who has been accused of Communist leanings’. Given a longstanding anti-Communist movement in Ireland, this news would have been of great interest. Guevara, from the beginning was one who was of special concern, with this early report noting that he was ‘the quickest mind’ of the revolution.[9]

Irish reaction to the Cuban revolution was largely tempered by pervasive anti-communism.

Many further articles featured the ‘young Argentine physician’, who, now tasked with transforming the Cuban economy, was becoming a focal point for western media, who spoke of him in terms of exoticism, intelligence, and as a dangerous influence. The Irish Independent again drew attention to his rising star, noting his pan-Latin American goals, which he hoped could become ‘another China’.[10]

Another from the same paper claimed that Guevara ‘appears to have the most powerful grip on the revolution’s steering wheel’, and had an eye on steering it ever more towards Russia.[11] Clearly positioned as the power behind the throne, Guevara was the ‘highly-trained Communist’, who the paper claimed, never ranted and raved as others in the new regime did. He was simply ‘the quiet, skillful, dangerous ‘Che’’.[12]

Such an image would have fascinated and unnerved conservative Irish readers in equal measure. The bogeyman of international communism had been an almost permanent feature of Irish life since the 1930s, when various Irish ‘Catholic Action’ groups became bent on hammering the anti-communist message home.

Now, at the dawn of the 1960s, as international communism was at new heights, Irish readers had vivid descriptions of an intelligent and charismatic trained doctor who was the leading figure of an emerging communist regime which had the eyes of the world upon it. There was no inkling that this man of mystery was one of the famed Irish diaspora.

Maureen O’Hara and ‘Che’

While the general Irish public, if they were interested, only saw glimpses of this ‘skillful and dangerous’ communist revolutionary, one of Ireland’s favourite stars was afforded a view of the human being behind the press persona. Internationally renowned Irish actress, Maureen O’Hara, fondly recalled her experience of the revolutionary leader in her 2005 biography ‘Tis Herself.

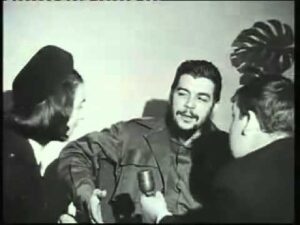

Internationally renowned Irish actress, Maureen O’Hara, fondly recalled her experience of the revolutionary leader in 1959

O’Hara tells of the multiple ‘interesting conversations with Che’ in the dining area of the Capri Hotel, where the crew of the 1959 film Our Man in Havana were staying. Claiming ‘Che would talk about Ireland and all the guerrilla warfare that had taken place there’, O’Hara was clearly in awe of the young charismatic Argentinean. She discovered that ‘he knew every battle in Ireland and all of its history’, which he learned, she insisted, from his grandmother ‘at her knee’.[13]

While we only have O’Hara’s account of the meetings, it does offer us an interesting insight to a man who had now become one of the international faces of the Cuban revolution.

Guevara’s brief visits to Ireland

Almost five years later, when Guevara’s transatlantic flight was diverted to Dublin, the Irish Press, contrary to what O’Hara would later write about grandmother Lynch, quoted Che was stating he knew little of his own grandmother, only presuming she was of Irish descent due to her surname.[14]

Perhaps Guevara, diverted on a long-haul flight was in little humour for press questions at this point. Making do with a mere presumption of lineage, the Irish Press was beaten to the punch by its fierce competitor the Irish Independent, which rolled out the green carpet with the front-page headline ‘Fog Bound in the Land of His Ancestors’,[15] capturing the Cuban minister’s walk on Irish soil from the grounded plane.

Guevara briefly visited Ireland in 1962 and 1965

This was not the only time Guevara had landed on Irish soil, with the first stopover occurring in 1962, when aspiring artist Jim Fitzpatrick met the subject of his future art piece.[16]

In March 1965, Guevara was in Ireland again, briefly after his plane was grounded in Shannon. The Independent was again to the fore of the coverage, stating that ‘the bearded leader’ and friends were intent on sampling the Limerick nightlife, ‘however, bingo, dancing, or ballad singing had no interest for the revolutionary’.[17]

It was during one of his Irish stopovers that Guevara was said to have written to his father from Limerick City: ‘I am in this green Ireland of your ancestors. When they found out, the television station came to ask me about the Lynch genealogy, but in case they were horse thieves or something like that, I didn’t say much’.[18]

After Che’s death

The ‘local angle’ on Guevara carried through in the wake of his 1967 execution, when numerous Irish newspapers, breaking the news, highlighted the deceased revolutionary’s Irish heritage.[19]

A year later, however, a hugely interesting Irish link was made by the Kerryman newspaper. In an article by Tony Meade, little is held back in a piece on Irish War of Independence veteran, Tom Barry. Sensationally titled ‘Tom Barry, The Che Guevara of Ireland’s Fight Against British Tyranny’, the article recapped the death of Guevara, a ‘remarkable man’ who took ‘on Goliath with his bare hands’.

Continuing, Meade’s article claimed that there were many in Ireland who mourned Guevara’s loss.

‘They were of two generations. There were those who staked their lives for freedom some fifty years ago and who, through their own efforts, saw freedom won in some considerable measure for their country. There was the smaller group which also took on an Empire, if by then a relatively toothless one, in the years, 1956 to 1962, and who swallowed the bitterness of defeat’.

Arguing that both groups knew the hard life of the guerrilla and that ‘for them Guevara was a fellow in action’, the article was quick to clarify lest anyone be accused of communist leanings, that they were not fellows in belief.[20]

The second generation the editorial referred to were those involved in Operation Harvest, the IRA’s border campaign of 1956-1962.

After his death, Guevara was compared by some in Ireland to figures such as Tom Barry, Dan Breen and Michael Collins

Today such an editorial in a mainstream Irish newspaper would certainly not go to print. Nevertheless, it does give us a snapshot of pre-troubles political reminiscing. Parallels would also be drawn between Guevara and leading figures of the Irish revolutionary period in later years. 1996’s biopic of Michael Collins saw its subject on more than one occasion compared with the South American revolutionary, especially when it came to guerrilla tactics. While at the century’s end, historian of the Irish revolution, Joe Ambrose made the claim that people like Dan Breen were inspirations to anti-imperialists like Che Guevara.[21]

Interestingly, there is some slight evidence of a link between Guevara and Barry. In 2011, the Irish Independent claimed that Barry’s War of Independence memoir, Guerrilla Days in Ireland ‘was so vivid’ it ‘subsequently became something of a handbook for guerrilla warfare, and Che Guevara reportedly carried a copy’.[22]

Historian Meda Ryan’s 2005 book on the Irish guerrilla leader, Tom Barry: IRA Freedom Fighter suggests there was an even stronger link, claiming Guevara wrote to Barry ‘acknowledging his achievements as a guerilla commander and asked if he would train and advise his men’. However, she states Barry turned down what was described as ‘a lucrative offer’ to do so.[23]

At the end of the 1960s, one of Ireland’s age-old problems, rural depopulation even evoked Guevara’s name during political debates on the matter. In a robust confrontation between Fianna Fáil’s Neil Blaney and Labour Party leader, Brendan Corish (who famously claimed in 1967 that ‘the Seventies will be Socialist’[24]), Blaney, ‘the cock of the Donegal walk’,[25] accused his opponent of inviting electors to forget Irish political traditions in the upcoming election:

‘Mr. Corish calls on the electors in this election to forget the politics of tradition (…) In other words forget the men of the past. Forget Pearse and Connolly, forget Tone arid Mitchel. Let us switch, he appeals, to the new heroes of the international revolution, the Che Guevaras, and the Danny the Reds’.

Continuing, Blaney warned ‘If he thinks that the people of this country are going to adopt the imported policies of such people and betray the leaders of their own past, then he is in for a shock’.[26]

Left wing activists and politicians in Ireland were also mocked by being called ‘aspiring Che Guevara’ by more conservative figures.

For some, however, it wasn’t a choice between ‘home grown’ or international revolutionaries. They could, in some cases coexist ideologically and share wall space. The Sunday Independent, a matter of months after Blaney’s jibes, found that Guevara was side by side with James Connolly in the offices of the Connolly Youth Movement in Sligo.[27]

The tone of the report, however, was consistent with most references to Guevara in Irish newspapers. Utilised in a pejorative sense, Guevara’s name was usually used by certain journalists to dismiss concerns of Irish students or workers, or to describe political figures which the mainstream baulked at.

For example, with tentative steps in the peace process slowly being taken in the mid-1990s, such as Section 31 of the broadcasting ban being lifted and Sinn Fein leader, Gerry Adams was granted a US Visa, the name of Guevara was again on the lips of journalist.

One journalist in particular argued that with Adams’ proposed visit to Irish America, he wasn’t likely to gain a receptive audience as Americans had enough to concern themselves without listening to the ‘verbal gymnastics of an Irish latter-day Che Guevara’.[28] While in December 2000, the Sunday Independent quoted Fianna Fáil’s Willie O’Dea as calling former Irish Republican Socialist Party member Nicky Kelly as ‘Arklow’s Che Guevara’.[29] Conversely, republicans who had taken part in ‘the Troubles’ looked upon comparisons with Guevara as a source of pride, particularly at times of commemoration, such as the twentieth anniversary of the 1981 hunger strikes.[30]

‘Romanticism of the guerrilla’

Nevertheless, as the Northern conflict grew in ferocity in the 1970s and 1980s, Guevara, despite having some roots in western Ireland, became a northern symbol in Irish papers, with any sense of his family’s ‘Irishness’ becoming harder to find.

The Sunday Press in March 1978, giving the impression of a world on fire, noted ‘in urban centres from Belfast to Bonn; Damascus to Athens; Los Angeles to Tokyo’ terrorist acts were growing ‘at an alarming rate’, with many of those committing the acts looking to Guevara who embodied ‘the romanticism of the guerilla’, and who helped keep alive ‘the revolutionary fervour of guerilla and terrorist alike’.[31]

That same month, in the Evening Herald an article on ‘Ideas of the Men of Violence’, Guevara and others were referenced in connection with the ideologies of the ongoing conflict.[32]

In August of 1989, marking the twentieth anniversary of the introduction of British Troops into Derry, the Irish Independent’s Justine McCarthy noted the welcome that British troops initially experienced from the nationalist people. The disintegration of that ‘very short friendship’, McCarthy went on to argue was now evident in the desolation of the Bogside, where burned out factories and graffiti of ‘Easter 1916’ sat alongside wall paintings of Che Guevara and Lenin.[33]

Che was adopted by militants Irish republicans as a figure of inspiration during the conflict in Northern Ireland.

One of the lengthier reports on Guevara’s life, came from the Evening Echo in 1990, charting ‘The Rise and Fall and Che Guevara’, it fully ignored any of the attention which had previously been placed on Guevara’s Irish heritage, instead opting for his revolutionary life of violence where he converted Castro to ‘full-bloodied communism’.[34]

Jon Lee Anderson, who would later publish a comprehensive study of Guevara, was the subject of an Irish Press article which examined Guerrillas: Journeys in the Insurgent World, Anderson’s study of various international insurgencies. Describing Guevara as a ‘handsome and romantic Irish-Argentinean’, the feature claimed Anderson’s research defines and outlines concepts that ‘would be familiar with us’, the ‘mythology, the romance, the resilience of subject peoples’. The article, nevertheless, distances the northern conflict from that discussion, arguing ‘not everyone would include Northern Ireland as a guerrilla fight’.[35]

The mid-to-late 1990s witnessed more serious attempts in mainstream Irish press to interrogate the history of Che Guevara as international attention fell upon Che’s legacy with the thirtieth anniversary of his death. This milestone alongside the publication of Anderson’s biography and the repatriation of the fallen revolutionary’s body to Cuba, all in 1997, saw a renewed interest in his life.

While by and large a more serious examination of Guevara’s history, the reporting in Irish newspapers was still muddled and there were few if any mentions of the Irish heritage. One would assume that such a milestone invited those connections in Irish newspapers.

Galway monument

Battles around the name and legacy of Guevara were fought sporadically on a variety of fronts. However, issues of Guevara and Irishness really came to the fore in the 2010s when proposals were raised to commemorate him and his links to Ireland. In 2012 a proposal for a permanent memorial in his ‘ancestral’ Galway was announced and in 2017 the official An Post stamp to mark the fiftieth anniversary of his execution raised the ire of conservatives in Ireland and abroad.

In 2012 it was proposed to erect a monument to Guevara in Salthill in Galway. The project was dropped after objections were raised.

The announcement in February 2012 of a proposed five-metre-high monument on the Salthill Promenade in Galway opened the floodgates. To the fore of those objecting was former mainstream journalist Kevin Myers, who in characteristic fashion categorised Guevara as a ‘vagrant sociopath, murderer, fantasist and narcissist’. Myers, hammering home his point (with echoes of recent sections of the unthinking MAGA crowd), states that ‘most of the industrial-scale mass murderers of the 20th century were socialists’, including Hitler.[36]

The Northern Irish press, especially the Belfast Newsletter picked up on the proposed statue and asked ‘Quite why the good people of Galway would want a statue of such an individual in their city centre is beyond me. It’s not as though he has any Irish blood in his veins’.[37]

Local businessman, and sometime pundit Declan Ganley also weighed in, describing the plan as having the potential to ‘damage the reputation of Galway around the world’.[38] Pressure was also added by US House of Representatives Foreign Affairs Chairperson, Ileana Ros-Lehtinen,[39] and Miami Congressman David Rivera, who both called for the project to be scrapped, leading to Galway Mayor Hildegarde Naughton to withdraw support.[40]

Stamp

In 2017 passions were aroused yet again with the announcement that An Post had commissioned a commemorative postage stamp to mark the fiftieth anniversary of Guevara’s killing in Bolivia. The opposition which was, for the most part, social media-driven was nonetheless picked up by traditional media outlets who questioned the Argentinean’s suitability for such an accolade.

Controversial commentator, Ruth Dudley Edwards was quoted in the Belfast Newsletter, describing Guevara as a ‘mass murderer’ a ‘lunatic’ and a ‘fanatic’ who ‘executed people for fun’, and claiming that associating with him would hurt the ‘Irish brand’.[41]

Unsurprisingly, the Irish Independent also captured the intense debate around the stamp. Counteracting claims that An Post were ‘glorifying a terrorist and a murderer’, Jim Fitzpatrick, the artist who had done so much to popularise Guevara’s image shone a light on Ireland’s own violent past by comparing the violence of the Cuban revolution to what took place during Ireland’s Civil War and how people can be swept up in violent circumstances.[42]

In 2017 An Post produced a stamp commemorating Guevara’s death fifty years earlier.

Irish President, Michael D Higgins articulated a more understanding position, stating: ‘I think it is a very, very good discussion if people would discuss Latin America. Every time we have a debate about Latin America it helps understand’.[43] The Donegal News, however, found the controversy ironic, given the General Post Office’s intimate historical connections with Irish revolutionaries.[44]

Conclusion

Connections between Che Guevara and Ireland have mainly been one way. Certainly, there is not much evidence to suggest that Che prized his Irish heritage in the way his father did. In fact, as Che’s letter to his father from Limerick in the 1960s stated that he was in the land of ‘your ancestors’, not ‘our’.

On the Irish side, however, it is much more prevalent, particularly among those with a republican or a socialist background. Does this indicate that in Ireland we sometimes have an overinflated view of our global history?

Connections between Che Guevara and Ireland have mainly been one way. Certainly, there is not much evidence to suggest that Che prized his Irish heritage in the way his father did.

Back in 2001, the Sunday Independent in an article on a Cuban trip by Austin Kenny claimed that the majority of Cuban’s hadn’t heard of Ireland, never mind Che’s connections with it.[45]

Within Ireland, for the most part, Che was either portrayed as a cunning and mysterious communist, or as an inspiration for international terrorism (post death). His identity in popular Irish press outlets was not fixed, changing sometimes with domestic political situations. His image as a member of the Irish diaspora certainly was emphasised with his stopovers in Ireland in the early to mid-1960s, when focus was on the mysterious Irish grandmother. When the world became aware of his death in Bolivia, many newspapers were keen to stress a local link with one of the world’s biggest news stories.

Ireland’s long and storied anti-colonial history also invited comparisons between those who fought Britain in guerrilla warfare and the most famous guerrilla fighter of the second half of the twentieth century. Figures like Tom Barry, Michael Collins, Dan Breen, and others, given their status in popular Irish memory were natural comparisons in many ways. However, Guevara’s communism made comparisons risqué given the power of social Catholicism in Ireland, with disclaimers being made to indicate those differences.

In recent times, controversies around Guevara’s Irish heritage, centred on memorialising efforts in Ireland have largely been driven online, often coming from Irish American and Cuban American sources. Issues around Guevara (and any associations with Ireland) polarise opinion on social media very quickly and feed into larger political and cultural identity tensions emanating from the United States, becoming part of these online ‘culture wars’.

References

[1] Jon Lee Anderson, Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life (London, 1997), p. 4.

[2] Che Guevara, Guerrilla Warfare (London, 1998), p. i.

[3] Michael E. Jones, “Che and Korda: A Convoluted and Contentious Cuban Copyright Case’, in Atlantic Law Journal, vol.15, (2013), pp 145-170.

[4] Bill Rolston, ‘The War of the Walls: political murals in Northern Ireland’ in Museum International, vol. 56, no. 3, (2004), pp 38-45.

[5] Connacht Tribune, 1 Mar. 2012.

[6] Anderson, Che Guevara, p. 21.

[7] Irish Times, 9 Oct. 2017.

[8] Ernesto Guevara Lynch quoted in I.R. Lavretsky, Ernesto Che Guevara (1976), p. 5

[9] Irish Independent, 20 Jan. 1959.

[10] Irish Independent, 30 May. 1960.

[11] Irish Independent, 22 May. 1961.

[12] Irish Independent, 25 Sept. 1961.

[13] Maureen O’Hara, ‘Tis Herself: A Biography (New York, 2005), p. 209.

[14] Irish Press, 19 Dec. 1964.

[15] Irish Independent, 19 Dec. 1964.

[16] ‘Che in Kilkee’ in History Ireland, Issue 4 (Jul/Aug 2008), Volume 16.

[17] Irish Independent, 15 Mar. 1965.

[18] Heinz Duthel, Illegal Drug Trade – The War on Drugs (2015).

[19] Evening Herald, 11 Oct. 1967., Irish Press, 12 Oct. 1967

[20] Kerryman, 17 Aug. 1968.

[21] The Nationalist (Tipperary), 4 Dec. 1999.

[22] Irish Independent, 13 Aug. 2011.

[23] Meda Ryan, Tom Barry, IRA Freedom Fighter (Cork, 2003)., Joseph McKenna, Guerilla Warfare in The Irish War of Independence 1919-1921 (North Carolina, 2011), p. 271.

[24] Richard Aldous, Great Irish Speeches (London, 2007), p. 121.

[25] JJ Lee, Ireland 1912-1985, Politics and Society (Cambridge, 1989), p. 82.

[26] Irish Press, 10 Jun. 1969.

[27] Sunday Independent, 22 Nov. 1970.

[28] Western People, 2 Feb. 1994.

[29] Sunday Independent, 10 Dec. 2000.

[30] Irish Examiner, 3 May. 2001., Donegal News, 27 Apr. 2001.

[31] Sunday Press, 19 Mar. 1978.

[32] Evening Herald, 3 Mar. 1978.

[33] Irish Independent, 12 Aug. 1989.

[34] Evening Echo, 24 Feb. 1990.

[35] Irish Press, 5 Feb. 1993.

[36] Irish Independent, 21 Feb. 2012.

[37] Belfast Newsletter, 25 Feb. 2012.

[38] Journal.ie, 1 Mar. 2012.

[39] City Tribune, 2 Mar. 2012.

[40] Irish Examiner, 7 Mar. 2012.

[41] Belfast Newsletter, 10 Oct. 2017.

[42] Irish Independent, 10 Oct. 2017.

[43] Irish Times, 9 Oct. 2017.

[44] Donegal News, 13 Oct. 2017.

[45] Sunday Independent, 18 Feb. 2001.