Treaties that Shaped the Course of Irish History

By John Dorney

Today, December 6 2021, is 100 years since the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty in 1921.

The Treaty or ‘Articles of Agreement’ created the Irish Free State as a self-governing dominion of the British Empire and confirmed the continued existence of Northern Ireland as an autonomous part of the United Kingdom.

To nationalist eyes, the Treaty represented either the culmination of centuries of struggle for an independent Ireland or, to its opponents, a base surrender of the Irish Republic declared by the First Dail in 1919. For this reason it tore apart the Irish republican movement in Civil War in 1922-23. It proved impossible for Michael Collins and his colleagues to persuade those who opposed the Treaty that it was a mere tactical move, ‘a stepping stone’ towards complete Irish independence.

The 1921 Treaty was signed against a background of what Irish nationalists thought of as 700 years of ‘broken treaties’.

To understand this visceral reaction, it is necessary to look backwards in Irish history and to see what Irish nationalists understood as a long history of broken treaties between ‘Ireland’ and ‘England’ dating back to the twelfth century.

A ‘Treaty’ is currently defined as ‘an international agreement concluded between States in written form and governed by international law’.[1]

Few, if any of the ‘treaties’ below meet this definition because Ireland was not a sovereign state at any of these points and were rather, from the English and later British viewpoint, merely internal agreements with ‘rebellious subjects’. The reality of such deals was usually, as ancient Greek historian Thucydides once put it ‘the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must.’

Treaty of Windsor 1175

During the fractious debates in the Dail over the Anglo-Irish Treaty on 19 December 1921, Arthur Griffith, one of the Treaties signatories, defended it by arguing that;

It is the first Treaty between the representatives of the Irish Government and the representatives of the English Government since 1172 signed on equal footing. It is the first Treaty that admits the equality of Ireland. [2]

He was referring to the Treaty of Windsor, signed between the High King of Ireland Ruaidhri Ua Conchobair (anglicised as ‘Rory O’Connor’) and King Henry II of England in 1175, acknowledging the overlordship of Henry over Ireland.

In 1175 Ruaidhri Ua Conchobair the last High King of Ireland recognised the overlordship of Henry II of England in return for his own position being recognised.

The first Anglo-Norman incursion into Ireland was made by mercenaries under Richard de Clare or ‘Strongbow’ in 1169, in the service of Diarmuid MacMurchada, the king of Leinster. Henry, the king of England (as well as Duke of Normandy and Count of Anjou), landed in Ireland two years later in 1171 when it looked as if Strongbow and his knights were being a little too successful, potentially carving out a kingdom of their own in Ireland. Henry proclaimed himself ‘Lord of Ireland’ with dominion over both the ‘English; and the ‘Irish’.

Whether the French-speaking nobility who had ruled England since the Norman conquest of 1066 could be classed as ‘English’ in the modern sense is a debate for another day. The point here is that they established in Ireland for the first time the jurisdiction of the Kingdom of England.

Ireland, before Strongbow’s arrival, was divided into many petty kingdoms and while there was a High King or Ard Rí, of Ireland, at the time Ruaidhrí, the king of Connacht, he did not preside over a functioning state. Rather he was the most powerful among a series of autonomous provincial kings.

Nevertheless Ua Conchobair fought back against the Anglo-Norman conquest. Aiding the King of Munster, his forces annihilated an Anglo-Norman army near Thurles in 1174 and made incursions into the province of Meath, forcing Henry II to open talks with him.[3]

In the Treaty of Windsor, Henry acknowledged Ruari’s position as High King, with the power to remove ‘rebel kings’ in return for Ua Conchobair acknowledging Henry as his ‘lord’ and paying him an annual tribute. Those lands already taken by the Anglo Normans, from Dublin to Wexford on the east coast, in Meath and from Waterford to Dungarven in the south east, could stay in English hands, but there would be no more incursions on territories held by the Irish kings.[4]

However the Treaty was soon broken. The land-hungry Anglo-Norman lords rapidly began expanding into almost all parts of Ireland. Henry II himself repudiated the Treaty in 1177 and named his son John as King of Ireland. That he never assumed his position was simply because Henry died suddenly in 1189 and John became King of England instead, with the ancillary title of ‘Lord of Ireland’.

Ruadhri Ua Conchobair was weakened by a factional struggle within his own kingdom of Connacht and abdicated in 1183, the last man to hold the title of High King of Ireland.[5]

Treaty of Mellifont

It took nearly four more centuries for the Kings of England to actually name themselves King of Ireland, as Henry VIII did in 1542.

This initiated a century long process whereby the Tudor monarchs, through fighting and negotiation truly established English state control over the whole of the newly minted Kingdom of Ireland. They also sought to impose their own ‘reformed’ religion.

The greatest resistance to this process came at the end of the 16th century in what is known as the Nine Years War (1594-1603 – the revolt with Spanish aid of the Ulster lords led by Hugh O’Neill and Hugh O’Donnell. O’Neill and O’Donnell initially hoped to prevent the intrusion of the Dublin administration into their own province of Ulster, but by the height of the war, claimed to be fighting Catholic crusade for an independent Irish kingdom allied with Spain.

Hugh O’Neill surrendered at Mellifont Abbey in 1603, marking the end of concerted Gaelic Irish resistance to the English conquest.

However, their defeat at the battle of Kinsale in 1601-2 meant that by 1603 they were reduced to guerrilla bands in Ulster, harried by the English forces and their native allies.

Peace was finally negotiated at the abbey at Mellifont County Louth on 30 March 1603, just after the death of Queen Elizabeth I.

At the Treaty of Mellifont, O’Neill, O’Donnell and the other surviving Ulster chiefs received full pardons and the return of their estates.

The stipulations were that they abandon their Irish titles (thus becoming Earls of Tyrone and Tyrconnell rather than O’Neill and O’Donnell), abandon the Brehon laws, private armies, their control over their uirithe (sub-kings) and swear loyalty only to the Crown of England.

The generous terms were not a result of clemency. The English Crown was facing bankruptcy from wars both in Ireland and Flanders and could not afford to carry on the war in Ireland any longer. In the long term, though, the war marked not only the end of the Nine Years War but the end of the Gaelic order. With the last independent military powers conquered, the true confiscation, Anglicisation and Protestantisation of Ireland could begin.

When in 1607, O’Neill, O’Donnell and other Ulster lords fled Ireland for Catholic Europe, in attempt to secure backing for a resumption of war, their lands were confiscated and from 1609 ‘planted’ extensively with Protestant English speaking settlers from England and from Scotland – the homeland of James Stuart, now King of England Scotland and Ireland.

While the Treaty of Mellifont was not referenced directly in the debates of 1921-22, Arthur Griffith did state, that the Treaty would lead to ‘Ireland developing her own life, carving out her own way of existence, and rebuilding the Gaelic civilisation broken down at the battle of Kinsale.’ [6]

Treaty of Limerick

Strange as it may seem to us, the Irish Catholic political cause over the following century was largely served, if served it truly was, by fighting for the line of Stuart Kings that held those three thrones.

In 1641-52, in the Eleven Years War, a Catholic Confederacy fought for ‘God King and Country’ against the English Parliament and their representatives in Ireland.

To some extent this was tactical, siding with the least anti-Catholic faction in England. Nevertheless the Confederates signed a treaty, the Ormonde Peace, with Charles II in 1649, putting their armies under his command in return for religious toleration, political autonomy and land restoration. Total defeat at the hands of Cromwell and the English Parliament led to mass confiscation of Catholic owned lands.

In 1689-91, again, Irish Catholics, as well as some Protestant royalists, fought for the ousted Catholic Stuart King, James II against his Protestant opponent William of Orange in the ‘War of the Two Kings’. After defeat at the battle of Aughrim and besieged in the city of Limerick, the Irish Jacobite commander Patrick Sarsfield threw off the advice of his French allies and capitulated to the Dutch general commanding the Williamite forces Godart de Ginkel.

The Treaty of Limerick, terms of surrender by the Irish Jacobite army in 1691 loomed large in nationalist consciousness as the ‘broken treaty’

Sarsfield signed the Treaty of Limerick, with Ginkel, under which he and over 10,000 Jacobite soldiers were to leave for France to continue to serve King James there in what became known as the ‘Flight of Wild Geese’.

The Treaty gave guarantees that no more Catholic owned land would be confiscated and no more discriminatory legislation would be passed against the Catholic religion than had existed prior to James’ accession to the throne.

These appeared to be highly conciliatory terms. The Anglo-Dutch alliance that William II headed had, after all no real interest in Irish affairs beyond ending it as a theatre of war with James and with France.

However, the now all-Protestant Irish Parliament, composed in the main of those whose landholdings and privilege were derived from expropriating and disenfranchising the old Catholic elite, was a very different proposition. They belatedly ratified the Treaty of Limerick in 1694-5, but deleted the clauses protecting Catholic landowners from confiscation, those which offered an ‘indemnity’ to those who had fought for James and those promising to respect the ‘religious liberties’ of Catholics.[7]

The Parliament then set about confiscating land from former Jacobite supporters and from 1695 onwards, passed series of Penal Laws against Catholics.

In some ways, the Jacobite cause, with its affinity for monarchs based in London and its identification of Irish nationality with religion sat uneasily with Irish republicanism as it later developed. Nevertheless, in the 1920s, the ‘broken treaty of Limerick’ was very much at the centre of Irish nationalist consciousness.

According to Joseph Lawless an IRA member from Dublin:

‘The name of Limerick was inextricably bound up with that Treaty of Sarsfield with William of Orange in 1691, the articles of which were dishonoured by the British Parliament as soon as the Irish army had safely left the shores of Ireland. “Remember Limerick” had been the battle cry of the Irish Brigades on the continent of Europe through the eighteenth century’.[8]

Another IRA veteran, Francis Healy of Cork, saw the ‘The Truce on 11th July, 1921, [as] being the first recognition of an Irish Volunteer Army since the Treaty of Limerick in 1691’.[9]

The Act of Union of 1801 under which the Irish Parliament was abolished and Ireland brought directly into the United Kingdom is not generally viewed as a ‘treaty’. Technically the Parliament voted itself out of existence.

However, there was again accusation of bad faith and broken promises. It was understood by many that ‘Catholic Emancipation’ that is the removal of the last of the Penal Laws, would follow the Union, but this did not happen. Instead it took a volatile mass mobilisation under Daniel O’Connell for this to happen in 1829. His subsequent agitation for ‘Repeal of the Union’ was forcibly suppressed in 1842.

Kilmainham Treaty 1882

If the Irish wars of the 17th century were in large part a struggle over landownership, so, in a very different way, were many of the struggles of the 19th century in Ireland.

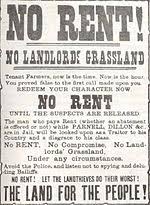

In the wake of the Great Famine of the 1840s, tenant farmers, now fewer but better organised, combined to resist evictions and the raising of rents. From 1879 with a slump in agricultural prices, this became an organised mass movement, mostly of civil disobedience nicknamed ‘the land war’, led by nationalist activists Michael Davitt and Charles Stewart Parnell in the Land League.

It was an article of faith for nationalists that the landlord class was also the ‘Protestant Ascendancy’ – the descendants of the colonists of the 17th century and that securing tenant rights was also part of the ‘reconquest of Ireland’.

This was a gross simplification of a more complex picture, for instance about 40% of landowners in late 19th century Ireland were Catholic, but it had enough truth for Parnell and the other Land League leaders to be seen by their followers as national leaders representing ‘Ireland’ and breaking the hold of the oppressive ‘foreign’ landed class over the country.

The co-called ‘Kilmainham Treaty’ of 1882 was therefore was far from an international agreement that the nickname implies, but it is significant that Parnell’s followers saw it in that light.

the term ‘Kilmainham Treaty’ reflected nationalist perception of the land war as a ‘national question’ and Parnell as national leader

It arose out of British Prime Minister William Gladstone’s second Land Act, establishing a land court to arbitrate rent disputes and eviction, though not applicable to tenant farmers in arrears or in debt.

In September 1881 Parnell urged his followers to ‘test’ the Land Act by trying arbitration boards, convincing Gladstone that he was trying to undermine the Land Act. In private though, Parnell thought that it ‘made landlordism intolerable’ by effectively giving ‘dual ownership’ of land to tenants. He was arrested on 20 October 1881, for ‘inciting tenants not to pay rent’ and imprisoned in Kilmainham Goal, in Dublin with the other League leaders. [10]

From prison, Parnell issued a ‘no-rent manifesto’, urging no tenants to pay rents, for which the Land League as whole was declared illegal under the Coercion Act. [11]

Parnell was finally released in April 1882 after negotiations dubbed ‘the Kilmainham Treaty’ in which he agreed to revoke the no-rent manifesto. In return Gladstone promised to wipe out arrears in rent owed by many of Parnell’s followers and to gradually drop ‘coercion’; that is the banning of organisations and imprisonment without trial.

The hard-line Chief Secretary for Ireland, William Forster, resigned in protest at Parnell’s release. His successor Frederick Cavendish, and the under-secretary, Burke, were assassinated in Dublin’s Phoenix Park within days of their arrival by a Fenian splinter group known as The Invincibles.[12]

Nevertheless, the Kilmainham deal gradually defused the conflict on the land. Under the Arrears Act, the state paid rent of £800,000 for over 130,000 tenants. Agrarian ‘outrages’ , that is violence against landlords and their property largely ceased by the end of 1882.[13]

Further concessions to Irish tenant farmers followed in the following decades, concluding with the Wyndham Act that subsidised tenants to buy out their holdings from 1908.

Anglo-Irish Treaty

This brings us to the Treaty of 1921. It was the fruit, in many ways, of the failure of British government to deliver on the much more limited self-government promised in Home Rule since 1912 in the face of Ulster unionist resistance.

Given their understanding of Irish history, this was widely seen by Irish nationalists as yet another example of ‘broken promises’ and double standards.

In 1912 Patrick Pearse warned that ‘If we are cheated once more there will be red war in Ireland’.[14] Kevin O’Shiel thought after British army officers at the Curragh refused to act against Ulster Unionists that, ‘after all it was but the old, old game all over again’.[15]

The failure to deliver Home Rule, allied to the radicalisation caused by the rising of 1916 and the demands of the First World War led to three years of political and military struggle from 1919-21 and a tangled peace process that eventually led to the Treaty.

As Griffith asserted, unlike all previous negotiations it was not talks about terms of surrender on the Irish side but something much more like a negotiation between equals.

The 1921 Treaty’s results were so divisive that it is still largely viewed negatively rather than as a ‘stepping stone’ to full independence.

The Treaty of 1921 was a short document, only 1,800 words long, containing 18 articles and a short appendix. It laid out that the Irish Free State would have the same constitutional status as Canada (self governing since 1867), subject to the Crown, to whom members of parliament would have to take an Oath of Fidelity and who would be represented in Ireland by a Governor General.

The Free State would have to pay its share of the Imperial debt and afford Britain three naval ports and ‘in time of war’…’all harbours as the British government may require.’ It was also committed to paying the pensions of the disbanded Royal Irish Constabulary except those ‘Black and Tans’ and Auxiliaries recruited since 1920.

As against this, the Irish state would have its own army and navy.

Northern Ireland, already operating since June 1921, could opt of the Free State and if it did so, a Boundary Commission would determine the border between the two. Neither government, Northern or southern could ‘endow any religion’ or ‘impose any disability on account of religious belief’.[16]

The Treaty said nothing about prisoner releases or British military evacuation, which had to be worked out subsequently in separate talks.

In many ways it was typical of British peace-making with restive possessions in the inter-war years; as in Egypt or Iraq, handing over formal control while attempting to keep control of its vital strategic interests.

The Treaty could thus be seen either, as its supporters like to portray it, as the culmination of Irish hopes of 700 years, or as a craven betrayal of republican aspirations, signed under duress by an unreliable partner, as the republican hardliners maintained. This of course led to an acrimonious split and ultimately to civil war.

Yet in truth it was the Irish side that gradually whittled away at the Treaty’s terms in later years; abolishing the Oath and Governor General in the 1930s and reneging on payments owed under the Land Acts. In 1938 a further Anglo-Irish Agreement ratified these changes and also handed back the ‘Treaty Ports’ and the Treaty’s stipulation of compulsory aid to Britain ‘in time of war’. This enabled the Irish state’s neutrality during the Second World War, in many ways the first real assertion of Irish independence.

The Treaty did in many ways prove to be a ‘stepping stone’ to greater independence, if not to a united Ireland. Despite this, the 1921 Treaty remains relatively unloved and unheralded today, seen rather through the prism of a history of broken treaties and surrenders rather than a national renaissance.

References

[1] Per the Vienna Convention 1969 Online here https://treaties.un.org/doc/Publication/UNTS/Volume%201155/volume-1155-I-18232-English.pdf

[2] Dail debates 19 December 1921, online here https://www.oireachtas.ie/en/debates/debate/dail/1921-12-19/2/

[3] Sean Duffy, Ireland in the Middle Ages, p.88. Meath in pre-conquest Ireland was considered to be one the five provinces of Ireland and was larger than the county of the same name today.

[4] Duffy, Ireland in Middle Ages , p.89-90

[5] Duffy, p.90-93

[6] For a resume of the terms of the Mellfont see Colm Lennon Sixteenth Century Ireland, The Incomplete Conquest, p. 301-302. For Griffith’s speech, Dail debates December 19, 1921.

[7] See Padraig Lenihan, Consolidating Conquest Ireland 1603-1727, p.209

[8] Joseph Lawless Bureau of Military History (BMH) WS 1043

[9] Francis Healy BMH WS 1694

[10] Joesph Lee, The Modernisation of Irish Society, p87-88

[11] https://www.encyclopedia.com/international/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/land-war-1879-1882

[12] Shane Kenna, The Invincibles and the Phoenix Park Killings, https://www.theirishstory.com/2012/07/31/the-invincibles-and-the-phoenix-park-killings-2/#.XFxrXqDgrIU

[13] Lee p.91

[14] https://www.irishexaminer.com/business/arid-20392254.html

[15] Fearghal McGarry, the Rising, p.73

[16] Liam Weeks, Micheal O Fathartaigh, The Treaty, pp275-283