The Treaty Debates: December 14 1921- January 7 1922

By John Dorney

On January 7, 1922 the Second Dáil, the parliament of the Irish Republic, voted to approve the Anglo-Irish Treaty, by seven votes, 64-57. Two days later Eamon de Valera failed by a mere two votes to be re-elected as President of the Irish Republic, unilaterally declared in 1919.

In protest at the approval of the Treaty, de Valera led his followers out of the assembly. They were followed by cacophony of abuse by pro-Treaty leader Michael Collins; ‘Deserters all!.. Deserters to the Irish nation in her hour of need!’

The Treaty debates have been variously depicted as the worthy ‘birth of nation’ or ‘fractious and bitter prelude to the Civil War.

Anti-Treaty TDs responded in kind: ‘Up the Republic’ shouted David Kent of Cork. ‘Oath breakers and cowards’ tossed back Constance Markievicz at Collins. ‘Foreigners! Americans, English!’ yelled back Collins in reference to the birthplaces of Eamon de Valera and Erskine Childers. His colleague Arthur Griffith also called Childers ‘a damn Englishman’ and refused to respond to his questions.[1]

Such was the bitterness that the Treaty debates engendered, in the previously united Sinn Féin party.

The debates have been variously praised as showing ‘great skill and insight’ on the part of the deputies present, in Peter Hart’s words, ‘an honest and profound starting point’ to the politics of the independent state, or more commonly they have been derided for their length, personal recrimination and failure to address the real issues at hand. In one recent work they have been summed up as ‘fractious and bitter’ and the discussions ‘poor and uninformed’.[2]

A contemporary, P.S. O’Hegarty wrote that in the ‘great talk’ in the Dáil there was ‘more hypocrisy, lying and moral cowardice than one would have believed to have existed in the country.’[3]

The great shadow that lies over the Treaty debates and the divisions which they exposed, is that they prefigured the intra-nationalist bloodletting in the Civil War of 1922-23.

While the body count of that Civil War is now thought to have been relatively low, with no more than 2,000 deaths, it shattered, not only the unity of the republican movement, but also the optimism and social renovation that might have accompanied the formation of the Irish state. Instead, among many of those who dominated Irish politics, all was recrimination and bitterness over the Treaty split for many years.

Among the 121 TDs who voted on the Treaty, at least ten died violently and many more suffered injury or debilitating spells of imprisonment as a result of the Civil War. [4] As a result, consideration of the Treaty debates is still mired in acrimony today.

This article is an attempt, not to pass judgement, but to sketch out the actual contours of the Treaty debates. What were the issues and how were they articulated by the two sides?

The Treaty

The Anglo-Irish Treaty was designed as the final settlement to the turmoil that had wracked Ireland since the attempted passing of a Home rule Bill in 1912 and especially an end to the guerrilla warfare which had raged over the previous three years.

It was signed in London by the Irish negotiating team, comprising of Michael Collins, Arthur Griffith, George Gavan Duffy, Eamon Duggan and Robert Barton, on December 6 1922.

The Treaty created the Irish Free State as a Dominion of the British Empire and stated that it would have the same self-governing status as Canada, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa. This included full legislative and fiscal autonomy for the Free State.

The symbolic head of state would be the British monarch, represented in Ireland by a Governor General. Members of parliament would have to take an oath of allegiance to the Free State’s constitution and of fidelity to the British monarch ‘in virtue of the common citizenship of Ireland and Great Britain’. However the constitution and form of government were for the Irish to determine themselves.

The Treaty’s 18 articles laid out the terms on which the Irish Free State would be founded as a self-governing Dominion of the British Empire.

Northern Ireland, created in 1920 by the Government of Ireland Act, had the option to opt in or out of the Free State and if it chose the latter, the border would be determined by a boundary commission ‘in accordance with the wishes of the population’. There would also be a ‘Council of Ireland’ where representatives of the two Irish parliaments would meet to discuss matters of common interest including ‘safeguarding of minorities in Northern Ireland’.

The Treaty permitted the Irish state to raise its own armed forces, subject to some restrictions and a naval force for the protection of ‘revenue and fisheries’ but the Royal Navy would continue to patrol the coast for at least five years until the Free State could conduct its own coastal defence. The British retained also three naval ports and the right to the use of all others ‘in time of war’.

The Irish state undertook to assume its share of the Imperial debt and to pay the pensions of police, judges and public officials ‘who are discharged by it’. This included the members of the Royal Irish Constabulary, except for the Black and Tans and Auxiliary Division recruited in Britain since 1920, who would be compensated by the British government.[5]

The British side walked out of talks on December 4 when the Irish delegation would not agree that the new state would come ‘into the Empire’. [6] For them this and an Oath to the monarchy were ‘red lines’ in the negotiations.

The Irish delegation were split, with Barton and Gavan Duffy proposing a revision of the Treaty, giving greater clarity to how a boundary commission would work and proposing ‘association’ rather than membership of the British Empire. They, along with Collins, Griffith and Duggan were ultimately persuaded to sign by Prime Minister Lloyd George’s threat of renewed ‘war within three days’ if they did not.[7]

The Treaty was narrowly approved by the Dáil cabinet back in Dublin, by four votes to three, despite the opposition of President Eamon de Valera who objected that the delegation had signed the final draft without first referring it to cabinet. Despite the reservations of Robert Barton and George Gavan Duffy, all of the members of the negotiating team voted to approve the Treaty, both in the cabinet and in the Dáil.

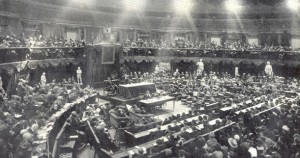

The Dáil debates on the Treaty convened on December 14, 1921 in the University College Dublin building on Earlsfort Terrace in central Dublin.

The Pro-Treaty case

The pro-Treaty case was that, while the Treaty was not perfect, it was the best that could be secured under the present conditions. In Griffith’s summary,

‘We have brought back the flag; we have brought back the evacuation of Ireland after 700 years by British troops and the formation of an Irish army. We have brought back to Ireland her full rights of fiscal control… equality with England [and] with the nations of the Commonwealth’.

In Collins’ famous words, ‘it does not give us ultimate freedom that all nations aspire to, but the freedom to achieve it’. He argued that Canada and other dominions would be ‘guarantors of our freedom’ and that the Treaty gave an opportunity to build ‘our future civilisation’.

Many echoed him, perhaps in spontaneous agreement, perhaps as result of briefing, describing the Treaty as a ‘stepping stone’ – Eoin O’Duffy and Peter Ward being two. Patrick Brennan of Clare stated, ‘This Treaty gives us freedom to achieve the ultimate liberty for which we all aim. That is enough for me’.[8]

Similarly Desmond Fitzgerald argued that the Treaty had some ‘limitations’ but that it would ‘establish justice, provide for future defence, secure peace at home and goodwill with all nations and to constitute a national policy based on the people’s will with equal right and opportunity for every citizen’.

The Treaty was in Collins’ phrase, much copied by other pro-Treaty deputies, ‘freedom to achieve freedom’

The Treaty in other words, its adherents argued, delivered much of the substance of Irish independence and progress could be made later on the areas in which it was deficient.

This was a difficult compromise to sell, however. On the other side, Harry Boland asked Michael Collins whether, if the Treaty was not a final settlement as Collins had stated, they were to ratify it merely with the intention of breaking it? Even if this were possible, Boland argued, it would lose for Ireland the ‘sympathy of the world’.[9]

Erskine Childers denied that the Treaty even gave Dominion status in the same manner as Canada. Under the Treaty he argued, the Irish state would not have control over its own coasts or have any choice on whether to enter a war of Britain’s choosing.

Whereas ‘Canada has a real and genuine share in the decision of those great questions of foreign policy, and on peace and war upon which the destiny of a nation depends. Ireland under this Treaty will have none.’[10]

Sean T O’Kelly similarly argued that since the Free State would have to give up its ports in wartime ‘regardless of whether the Irish Free State so willed or not … I call it, with the President, a Treaty of surrender’.

Of Plenipotentiaries and Oaths

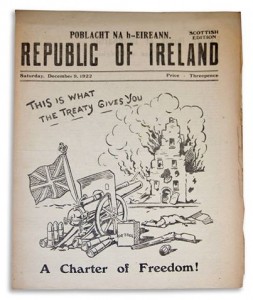

Anti-Treaty Republican propaganda during the Civil War would maintain that; ‘The Treaty was a betrayal, signed behind the back of the President’ and a great deal of wrangling would go on during the Treaty debates in the Dáil over whether the delegates had the right to sign the document at all without having first referred back to the cabinet.[11]

According to Liam Mellows, ‘they went as the Envoys Plenipotentiary of the Irish Republican Government, and, as such, they had no power to do anything that would surrender the Irish Republic.[12]

In fact though, this issue, from a legal standpoint was clear enough. The delegation as ‘plenipotentiaries’ had the full right and authority to conclude an agreement. Eamon de Valera conceded as much on the first day of the Dáil debates:

Now I would like everybody clearly to understand, and the delegation on the one hand and we on the other have agreed to this, that the plenipotentiaries went over to negotiate a Treaty, that they could differ from the Cabinet if they wanted to, and that in anything of consequence they could take their decision against the decision of the Cabinet, but of course they would know the consequence.[13]

De Valera’s own position was one of the most divisive in the assembly. The Pro-Treaty deputies, especially Collins and Griffith, noted that at the outset of talks in July 1921, de Valera had accepted that in order for a peace deal to be reached, there would have to be compromise with the British on the Irish Republic declared in 1919, and this again, at least initially, de Valera accepted publicly.

He stated on December 14 that he had never ‘made a statement that I was altogether for the Republic or nothing’ and in pursuit of peace he knew he would have to ‘batter down the wall of the isolated republic to do it’.[14]

Eamon de Valera’s position was to reject the Treaty but to promote an alternative ‘external association’ with the British Empire.

Why then, the pro-Treatyites wanted to know, if he knew that ‘an isolated republic’ was not possible, would he not stand by the ‘honourable’ compromise that the delegation had signed? For many, the reasons were suspected to be tied up in personal jealousies with his cabinet colleagues. De Valera’s response however, was that any ‘association’ with the British empire would have to ‘palatable’ to the republican grassroots. He proposed ‘external association’ without an Oath of Allegiance.

In summing up he claimed that ‘I had pinned, personally, my efforts to get the idea of any association whatever with the British Empire—or the States of the British Empire—to try to make that palatable … to those who thought, not merely of an independent Ireland in the sense of being a sovereign state, but thought of Ireland as a sovereign state absolutely isolated, such as Switzerland. I had attacked it as a political problem. I had kept myself detached, so to speak, calmly, coldly weighing the factors in the situation.’[15]

Some of his Cabinet colleagues, notably Cathal Brugha, the Minister for Defence backed de Valera’s ideas. In a bad-tempered contribution, in which he claimed the British had ‘selected the weakest men and intimidated the other two’ into signing, Brugha condemned the Treaty as ‘national suicide’ because it meant ‘wilfully, voluntarily admitting ourselves to be British subjects, and taking the oath of allegiance voluntarily to the English King’. But he argued that;

‘We are prepared to enter into an agreement, an association with the British Commonwealth of Nations as it is generally called, on the same or similar lines as that on which one business firm enters into combination with another or several others… we are prepared to recognise the English Government as the head of the combination.’

Now, instead of becoming British subjects or British citizens we will have reciprocal citizenship, that is, an Irish citizen or British subject will have the support of this group in any part of the world where he may find himself where he will require help. He will have the power of the new group behind him.[16]

Treatyites tended to think of this as mere sophistry, in Griffith’s words ‘a quibble over words’, in those of Sean Milroy and Kevin O’Higgins ‘a shadow’. Many other pro-Treaty TDs including James Burke of Tipperary and Alexander McCabe of Sligo would make the point to the purist Republicans that the choice was not in fact between the Treaty and the Republic but between the Treaty and another, in their view scarcely different, compromise. But rejecting one for the other could well mean war.

At least one self-described ‘doctrinaire republican’ Patrick MacCartan, accepted the validity of this argument and voted for the Treaty on the basis that a Republic was not on the table and that the only alternative to the Treaty was ‘chaos’. [17]

However many other anti-Treaty Republicans had no time for any compromise. For them it truly was the Republic or nothing. Of these, Liam Mellows was probably the most eloquent. He declared that he was ‘against any form of compromise’.

Either the Republic exists or it does not. If the Republic exists, why are we talking about stepping towards the Republic by means of this Treaty? I for one believed, and do believe, that the Republic exists, because it exists upon the only sure foundation upon which any government or republic can exist, that is, because the people gave a mandate for that Republic to be declared… This Treaty destroys the existing Irish Republic. Whether we like it or not we become British subjects, British citizens. [18]

If this was the peace settlement, Mellows argued ‘why was the fight ever started?’ A Home Rule Bill with limited autonomy had after all been available all along.

This point was echoed by a great many others. Ada English, for instance, of the National University of Ireland, described the Treaty as ‘a sin against Ireland’ because of the oath ‘to the English king’. Mary MacSwiney said that she would choose war and even the ‘extermination of Ireland’ before such ‘dishonour’.

A generous reading of de Valera’s line was that such people had to be brought on board with the compromise peace and the existing Treaty was not capable of doing so. Whether de Valera’s ‘Document no. 2’, which Griffith leaked to the press during the debates, would have been capable of doing so either is also open to question. In any case, for pro-Treatyites, such talk of existing Republics and war before dishonour was dangerously abstract.

Many Republicans notably Liam Mellows were not prepared to make any compromise on the existence of the Irish Republic declared in 1919.

Piaras Beaslaí for instance criticised the anti-Treaty deputies for confusing ‘what are called principles, but are really political formulas…Their dry political formulas are more important to them than the living nation’.

Beaslaí stated that the immediate result of the rejection of the Treaty would be that 60,00 British troops and 15,000 police would remain in Ireland and that 2,000 prisoners would remain in British jails.[19]

He stated that he supported the Treaty because: ‘We can make our own Constitution, control our own finances, have our own schools and colleges, our own courts, our own flag, our own coinage and stamps, our own police, aye, and last but not least, our own army.’

He accused anti-Treaty deputies of ‘lack of faith’ in the ability of the Irish people to develop the terms of the Treaty to their own benefit.[20] Similarly JJ Walsh of Cork objected to the ‘ju-jitsu of oaths’, which he contrasted with the substance of the Treaty.

Desmond Fitzgerald and others argued that the Republic declared in 1919 was no more than a a ‘means to an end’, ‘one of the weapons used in fighting for the freedom of our country’ and that the place of the King was ‘no more than a symbol of state’. [21]

The memory of the dead and the ‘tyranny of the British Empire’

It is necessary to account for the intensity of anti-Treaty emotion against the Treaty.

Part of it was brought on by the struggle and sacrifices of the movement and often the deaths of relatives and friends in the conflict. Mary MacSwiney spoke of her brother Terence, the mayor of Cork, who had died on hunger strike in 1920, Kathleen Clarke of her husband Tom, Margaret Pearse of her sons Patrick and Willie, all executed in 1916, Kate O’Callaghan spoke of her husband the mayor of Limerick, assassinated by British forces in March 1921.

O’Callaghan maintained that ‘no woman is going to give her vote because she is warped by deep personal loss’. Nevertheless she asked, ‘What has been the agony and the sorrow for? Why was my husband murdered? Why am I a widow? Was it that I should come here and give my vote for a Treaty that puts Ireland within the British Empire? Was it that I should take an oath to be a faithful citizen of the British Empire?’.

Many anti-Treaty deputies asked ‘what was the struggle for?’ and talked about those who had died for the Irish Republic.

Such sentiments were widespread, expressed by many anti-Treatyites. How could the sacrifices of the past be redeemed by a mere compromise? On the other hand the pro-Treaty deputies, who had been through the same struggle, asked whether rejecting the Treaty would lead to final victory or just more death for no tangible result.

Liam Hayes of Limerick argued that as an IRA officer he had asked men to sacrifice their lives for Irish freedom. He now held that ‘we have won’ in that the British forces would leave and future the Irish people ‘would control their own destiny’. He could not ask ‘his comrades’ to sacrifice their lives ‘for a mere change of words’.[22]

Pro-Treatyite from Kerry, Fionáin Lynch complained that ‘the bones of the dead have been rattled indecently in this assembly’.[23]

If the memory of the dead formed one visceral objection to the Treaty, another was antipathy to the British Empire as a whole. While some were at pains to maintain that they had ‘no desire’ as Art O’Connor put it, ‘be at variance with the English people’ who were ‘decent’, many viewed the British Empire as a malignant ‘tyrannical’ institution.[24]

Mellows declared that:

The British Empire represents to me nothing but the concentrated tyranny of ages. You may talk about your constitution in Canada, your united South Africa or Commonwealth of Australia, but the British Empire to me does not mean that. It means to me that terrible thing that has spread its tentacles all over the earth, that has crushed the lives out of people and exploited its own when it could not exploit anybody else.[25]

Donal O Buachala called the Union flag; ‘the symbol of oppression and treachery and slavery in this country, and all over the world’.[26]

While TDs like Mellows and Markievicz decried ‘going into the British Empire’, pro-Treaty deputies such as Gearoid O’Sullivan responded that the Irish were already soldiers and administrators of Empire across the world.

Ireland, many anti-Treatyites would argue, was not a loyal colony like Canada or Australia – ‘the children of England’ as Austin Stack called them – but a ‘subjugated nation’ like India or Egypt. Mellows argued that by voluntarily entering the British Empire, Ireland would be responsible for the ‘crucifixion of India’ and the ‘degradation of Egypt’.[27]

Similarly, Constance Markievicz argued that the Treaty, ‘binds us to stand by and enter no protest while England crushes Egypt and India’.

The pro-Treaty rejoinder was that Irish men and women were already engaged in garrisoning and running every part of the British Empire. As Gearoid O’Sullivan argued ‘The greatest Anglicisers of the world have been the Irish. We, the Irish people, have been Empire builders for England all over the world’.

He referenced Irish civil officer Michael O’Dwyer whose administration in the Punjab had overseen the Amritsar massacre in 1919 and the Irish soldiers who had ‘shot the Indians down’. He stated that the Treaty would end active Irish participation in the British Empire and be ‘good for humanity’. Instead now, O’Sullivan argued, Ireland would now participate freely in the League of Nations as a sovereign country.[28]

W.T. Cosgrave argued that as a Free State, Ireland could, with its standing as a sovereign Dominion, now ‘stand by these oppressed peoples’, whereas previously it was powerless.[29]

A Workers Republic?

One thing that is not very apparent in the Treaty debates is a fundamental split on the social content of the prospective Irish state. Markievicz did state that she was for ‘James Connolly’s ideal of a Workers’ Republic’ and objected to Arthur Griffith consulting with Southern Unionists on their representation in the upper house in the Free State’s parliament.

They, as ‘capitalists’ and the ‘English garrison’ would, she maintained,

‘block every ideal that the nation may wish to formulate; to block the teaching of Irish, to block the education of the poorer classes; to block, in fact, every bit of progress that every man and woman in Ireland to-day amongst working people desire to see put into force. That is one of the biggest blots on this Treaty; this deliberate attempt to set up a privileged class in this, what they call a Free State, that is not free.’[30]

However, this was not a common anti-Treaty line. Pro-Treaty TD Joe McGrath, who also, like Markievicz, represented a working class district of Dublin, was the one deputy to quote from the Democratic Programme, the left-of-centre social programme of the First Dáil in 1919, which pledged to ensure the ‘physical moral and spiritual well-being’ of the citizens of Ireland and that ‘no child should suffer from hunger, cold or lack of clothing or shelter’. McGrath argued that under the Treaty ‘every single thing in the Democratic Programme can be put into force’.[31]

Socialist Republicanism would emerge from the Civil War era as one legacy of the anti-Treaty side, but it was not a strong element of the Treaty debates.

A brand of socialist Republicanism would eventually emerge from the Civil War era as one legacy of the anti-Treaty side, but it was not a strong element of the Treaty debates in the Dáil.

Similarly, although all six women TDs voted against the Treaty, none of them mentioned what would be termed today ‘women’s’ or feminist issues. Indeed, Markievicz mentioned England’s liberal ‘divorce laws’ as one of the objectionable features of ‘English’ civilisation that Southern Unionists would bring.[32]

The question of land ownership and redistribution, still a major issue in Ireland in 1922, did not come up at all in Treaty debates. But then, the eighteen articles of the Treaty did not cover land, labour or social questions either. The debate was therefore essentially about independence and sovereignty. The rest lay in the future.

Partition

It has become a commonplace in Irish historiography to say that the Treaty debates in the south ignored the issue of partition in favour of arguing over how independent the southern Irish state would be. And certainly, the status of the emerging Irish state was the principal concern of the overwhelmingly southern-based deputies.

The side-lining of partition has been exaggerated, however. Firstly, the pro-Treatyites, in the main were just as much against partition as those opposed to the Treaty. In fact, Collins had assured the Northern IRA in private, that ‘although the Treaty might have been an outward expression of partition, the Government had plans whereby they would make it impossible and that partition would never be recognised even if it meant smashing the Treaty’.[33]

However in the Dail, Collins argued that the Treaty itself would end partition, without ‘coercion’ that it would lead to ‘goodwill’ and the voluntary entry of the ‘North East corner’ into the Irish parliament ‘within a short time.’[34]

The idea that members of the Second Dail were not exercised by the issue of partition has been greatly exagerrated.

In this he was echoed by Ernest Blythe, the only northern Protestant deputy, who argued that ‘material [or economic] reasons’ would see Irish unity within ‘a comparatively short time’ sentiments echoed by, among others WT Cosgrave, Kevin O’Higgins and Eoin O’Duffy.[35]

Indeed O’Duffy, who had spent much time as an IRA officer during the War of Independence along the border and in Belfast during the Truce, argued that if the Treaty were rejected the principal victims would be ‘our Catholic people in Ulster’ who would be at the mercy of the ‘atrocities’ of the ‘A and B Specials’ [Ulster Special Constabulary].’[36]

In sum, a vote for the Treaty was not perceived as a vote for partition in early 1922.

Secondly, many anti-Treatyites did bring up the question of partition during the debates, though Seán MacEntee, a native of Belfast representing Monaghan, was perhaps the only one who made the articles on Northern Ireland his main angle of attack. He stated that the Treaty ‘perpetuates partition and perpetuates our slavery’ by ‘making evacuation [of the British military] a mockery’, as British troops would simply be transferred across the border.

He told the pro-Treaty deputies that ‘the six counties [Northern Ireland] … have a right to vote themselves out from under the operation of your Treaty, and you are making no provision whatsoever to bring them in. Don’t tell me that is not partition.’

Regarding the Boundary Commission, he argued that it’s granting of more territory to the Free State depended entirely on British goodwill and in particular that of Lloyd George; ‘I don’t trust him, but I never saw such guileless trust in any English statesman as those who are standing for this Treaty are giving him.’ In any case, MacEntee maintained that he was against partition on any lines, even if border areas were granted to the southern state.[37]

A significant number of other anti-Treatyites also brought up the issue. Ada English maintained that ‘Ulster is still part of Ireland’ but would still be garrisoned by British troops. Mary MacSwiney stated that she was against ‘legalised partition’.

Eamon Dee of Waterford said the Treaty was ‘a permanent barrier to Irish unity’. Thomas Derrig of Mayo stated that he could not ‘see any prospect in the future where we can get Ulster in’. Sean Moylan of Cork warned deputies that if the Treaty were approved, Northern Ireland would be ‘a new Pale’ with ‘an army entrenched on our flank’ and they would ‘abandon their own people in the North in the same loathsome way’.[38]

Narratives that claim that the question on partition was not of concern to deputies in the Second Dail, therefore, need to be revised.

On the other hand, it is true to say that the Northern nationalist, let alone Northern Unionist viewpoint, was sorely under-represented in the Treaty debates. Oddly, the one TD who solely represented a Northern constituency, Sean O’Mahoney, who represented Fermanagh-Tyrone, but who was himself from Kilkenny, opposed the Treaty and spoke against it but said nothing about partition.

War and rumours of war

One of the main pro-Treaty arguments for accepting the settlement was that the those who knew ‘the Army’ (the IRA) best knew that there was no chance of military victory should the war against Britain be renewed. Indeed IRA GHQ Staff were almost unanimously pro-Treaty.

Collins himself, who had held the role of IRA Director of Intelligence, maintained that the Irish ‘were not in the positions of conquerors dictating peace to a vanquished foe’.[39]

Richard Mulcahy, the IRA Chief of Staff stated that, ‘none of us want this Treaty’, especially ‘harbours occupied by enemy forces’ and partition. But the alternative was ‘political chaos, with or without war’ and ‘we are not in a position of force, either militarily or otherwise’ to drive out British forces. They had in fact, ‘been unable to drive the enemy from anything but a fairly good sized police barracks’ and were ‘certainly not able to win a war of national liberation.’[40]

This view was backed up by the likes of Sean MacEoin, Sean Hales and Eoin O’Duffy, all with impeccable ‘records’ as fighting IRA officers. MacEoin for instance stated that though he was prepared to go back to war if necessary, the Midland Division under his command had only one rifle for every fifty men and ammunition for less than an hour’s fighting per rifle.[41]

On the other side, the lauding of Collins in particular as ‘the man who won the war’ irked many, prompting some bitter personal attacks. Cathal Brugha as Minister for Defence, maintained that Collins was merely ‘head of one of the sub-sections of my department’ who had ‘sought notoriety’ with the press. He and Seamus Robinson of Tipperary asked whether Collins had ‘ever in fact fired a shot at the enemies of Ireland?’[42]

Sean Nolan of Cork maintained that contrary to the picture painted ‘We were winning [before the Truce], and we will win.’ Sean O’Mahoney called on IRA members to ignore ‘such transparent political expediency on the part of a majority of their Headquarters Staff’. [43]

Some anti-Treaty deputies who were also IRA officers declared that they were ready to go back to war rather than accept the Treaty. Sean Moylan of Cork stated that ‘If there is a war of extermination waged on us, that war will also exterminate British interests in Ireland; because if they want a war of extermination on us, I may not see it finished, but by God, no loyalist in North Cork will see its finish, and it is about time somebody told Lloyd George that’.[44]

Less aggressively, Harry Boland maintained that ‘the greatest tragedy to my mind has been the defeatist speeches of the heads of the army’. He, argued that as a result of importation of arms in recent months, the IRA was now in a much stronger position than in the previous year. Besides, he argued Britain had no troops to spare with revolts underway in India which was ‘in flames’ and Egypt where ‘[General] Allenby needs 90,000 men’. British threats of war in other words, were a bluff [45]

The Treaty debates saw much rancour over the part various deputies had played in the War of Independence and rival assertions on the IRA’s strength.

There were also rumblings during the debates of the future conflict over the Treaty. Several anti-Treaty TDs including de Valera warned that it would not bring peace. Mary MacSwiney declared that if the Treaty were passed she would immediately become a ‘rebel against the Free State’. Con Collins of Kerry worried that under the Free State ‘us Republicans would spend the rest of our lives in jail as rebels’.[46]

More ominous still, at the start of the debates, Michael Collins felt the need to ask Cathal Brugha about reports that in Cork anti-Treaty Volunteers had threatened to shoot any deputy who voted for the Treaty. Brugha, abrasive as ever, simply stated that he ‘could not deal in rumours’ and told deputies that they should ‘keep their mouths shut’ and not repeat rumours.[47]

The ‘will of the people’

This brings us to the final and perhaps the strongest part of the pro-Treaty case. That the Treaty, whatever its faults was ‘the will of the people’; who above all desired peace. This was evidenced by the flood of resolutions by public bodies such as county councils over the Christmas break, urging TDs to ratify the Treaty.

Many Treatyites contended that they were swayed by the wishes of their constituents. Richard Corish of Wexford for instance said that the Treaty was not ‘entirely in accordance with my views’ but that ‘it is the best thing for the country at the moment and my constituents want me to vote for it’. Similarly Daniel O’Rourke of Mayo stated that he could not side against his constituents who were ‘overwhelmingly’ in favour of ratification and many others, including Vincent White of Waterford and Peter Ward of Donegal said likewise.[48]

The Pro-Treaty side insisted that the Treaty was ‘the will of the people’

Griffith asserted that ‘we are representatives not dictators of the Irish people’ and Collins that the ‘consent of the governed’ was the most important republican principle, sentiments echoed by pro-Treaty stalwarts such as Sean Milroy, Sean McGarry and others.

Collins’ role as President of the Irish Republican Brotherhood probably helped in shaping a ‘party line’ such as this, though among IRB members in the Dáil, only a fairly slim majority, 25-19, voted for the Treaty.[49]

On the other side, this was a difficult argument to counter, especially as many pledged themselves to the ideal of republican democracy. None of them, contrary to later caricature, advocated a dictatorship to block the Treaty’s acceptance.

However, many asserted the ‘principle’ was more important than constituents’ wishes. Harry Boland for instance stated that his constituents knew that he stood for an Irish Republic and if they disagreed they were free to vote out him at the next opportunity. TDs such as Art O’Connor, Edward Aylward and others made similar statements.[50]

The most powerful rejoinder, though, came from Liam Mellows. The public support for the Treaty was not, he maintained the ‘will of the people’ but the ‘fear of the people’ brought on by British threats of war. ‘The will of the people was when the people declared for a Republic.’[51] In Padraig de Burca’s powerful description, Mellows, ‘with fair hair brushed back [and] rugged countenance lit by profound conviction,’ read out the Declaration of Independence from 1919, ‘and I’ will make no apology for its length or the time it will take’. “There”, he declared, striking the table with his hand, “is the will of the people” ’.[52]

The Vote and the split

Some of the most intemperate speeches including Brugha’s attack on Collins and others were given just before the vote on the Treaty, with was held late in the evening of January 7 1922.

Though some TDs represented more than one constituency, they maintained the principle of ‘one man one vote’ and declined to vote twice. Eoin MacNeill, the speaker, did not vote and three TDs were absent.[53]

The process of voting was described as ‘painfully slow’, but when the result in favour of the ratification of the Treaty was passed ‘a mighty cheer’ was heard from the crowd waiting outside the chamber.[54]

Eamon de Valera, ‘whose features now wore a deathly palour’ declared ‘the Irish Republic goes on until the national disestablishes it’. He and Collins both appealed for unity.[55]

It is difficult to say whether the arguments of the previous weeks had changed many minds but they had certainly hardened divisions that had emerged over the Treaty.

It is difficult to say whether the arguments of the previous weeks had changed many minds but they had certainly hardened divisions that had emerged over the Treaty.

What lay ahead were months of acrimony and ultimately of bloodshed before the Free State was eventually established.

References

[1] Quoted in Liam Weeks, Michael O Fathartaigh, Birth of a State, The Anglo Irish Treaty, p.106-17 (IAP 2021). Since the British did not recognise the Dail, 66 pro-Treaty TDs reconvened a week later in Dublin’s Mansion House as ‘the Parliament of Southern Ireland’ and voted unanimously to approve the Treaty, satisfying British requirements. Anti-Treaty TDs did not attend.

[2] For Hart, see Mick the Real Michael Collins, p.327. (Pan Books 2005), For a more negative assessment, Weeks, O’ Fathartaigh, Birth of a State, p.123.

[3] PS O’Hegarty, the Victory of Sinn Fein, p.59. (UCD Press 2015).

[4] They were; on the pro-Treaty side, Michael Collins killed in an ambush in August 1922, Sean Hales and Seamus Dwyer assassinated in separate incidents in Dublin in December 1922 and Kevin O’Higgins assassinated in 1927. On the anti-Treaty side, Cathal Brugha was killed in Dublin in the first week of the Civil War in July 1922, Harry Boland was shot and mortally wounded during arrest later that month Seamus Devins was killed along with five others on Ben Bulben in Sligo in September 1922, Erskine Childers and Liam Mellows were judicially executed by the Free State in November and December 1922 respectively and Joseph MacDonagh died as a result of hunger strike in December 1922. To these can be added Arthur Griffith who died of a stroke , probably brought on by the intense stress of Civil War in August 1922 and Sean Etchingham who died shortly after release from imprisonment in 1923.

[5] For the Treaty’s terms in full see, Week, O Fathartaigh, eds, The Treaty, Debating and Establishing the Irish State, (IAP 2018), p.275-285

[6] Charles Townsend, The Republic, The Fight for Irish Independence (Allan & Lane 2013) p.349

[7] Dorothy McArdle, The Irish Republic, *Corgi, 1968) pp. 527, 530, 535.

[8] Dáil Debates Dec 14-19 1921. Brennan’s speech Jan 7 1922 Mel Farrell notes that Daniel McCarthy, TD for Dublin South and President of the Gaelic Athletic Association, ‘put his skills to good use as whip of the embryonic pro-Treaty party’. Farrell, ‘Stepping Stones to Freedom’, Pro-Treaty Rhetoric and Strategy During the Dáil debates, in Week O Fathartaigh, The Treaty, pp.18,20-22

[9] Dáil debate Jan 6 1922

[10] Dáil debates 19 December 1921

[11] ‘Address From the Soldiers of the Republic to their former comrades in the Free State Army’, December 1922, Twomey Papers, UCD P69/76.

[12] Dáil debates Jan 7 1922

[13] Dáil debates December 14 1921

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid. Jan 7 1922

[16] Ibid, Jan 7 1922

[17] Dáil debates Dec 21 1921.

[18] Dáil debates Jan 7 1922.

[19] Dáil debates Jan 6 1922. Over 4,000 internees had been freed by this point but most of those who had been tried and convicted were still imprisoned, many in Britain itself.

[20] Dáil debates January 6 1922

[21] Dáil debates 4 Jan 1922

[22] Dáil debates Jan 6 1922

[23] Dail Debates Dec 20, 1921

[24] Dáil debates, 3 January 1922

[25] Dáil debates Jan 6 1922

[26] Dáil debates Jan 6 1922

[27] Dáil debates Jan 6 1922

[28] Ibid.

[29] Dail debates Dec 21 1921

[30] Dáil debates

[31] Dáil debates Jan 7 1922

[32] Dáil Debates

[33] Cited in Kieran Glennon, From Pogrom to Civil War, Tom Glennon and the Belfast IRA (Mercier 2013) p. 147.

[34] Dáil debates Dec 19 1921

[35] Dáil debates, Dec 19, Jan 6 1922

[36] Quoted in Macardle, the Irish Republic, p.575.

[37] Dáil debates 22 December 1921

[38] Dáil debates, December 19, 22, 1921, Jan 6, 7 1922.

[39] Dáil debates 19 Dec 1921

[40] Dáil debates 22 December 1922

[41] Farrell, ‘Stepping Stones’ in The Treaty, p.22

[42] Dáil Debates January 7 1922

[43] Dáil debates 4 January 1922

[44] Dáil debates December 12 1921

[45] Dáil debates Jan 6 1922

[46] Dáil debates 21 Dec 1921, 7 January 1922

[47] Dáil debates December 16 1921

[48] Dáil debates December 14 1921 to Jan 7 1922.

[49] For the IRB angle, Weeks, O Fathairtaigh, Birth of State, p.86. On December 12 the IRB Supreme Council ordered its members to accept the Treaty. Nevertheless, in the vote, only 25 TDs who were also IRB members voted for the Treaty compared to 19 who voted against.

[50] Dáil debates 14 Dec 1921 to 7 Jan 1922

[51] Dáil debates, January 4, 1922,

[52] Padraig De Burca, John F Boyle, Free State or Republic, (UCD 2015), p.45. Also Dáil debates Jan 4 1922.

[53] They were Frank Drohan, Laurence Ginnel and Thomas Kelly, Weeks O Fathartaigh, The Treaty, p. 307.

[54] De Burca, Free State or Republic, p.69

[55] Ibid.