Today in Irish History – January 16 1922, The handover of Dublin Castle – or was it?

By John Dorney

In January 1922, with the Anglo-Irish Treaty ratified in British and Irish parliaments[1] events in Ireland began to move at a rapid pace. British authority in Ireland was to be handed over to a ‘Provisional Government’, that would oversee the handover of power to the Irish Free State.

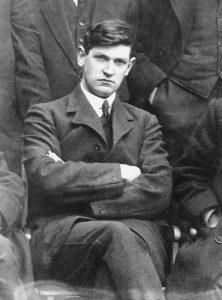

The Provisional Government, headed by Michael Collins was able to point, to its detractors, to several immediate benefits of the Treaty, including the release of prisoners and the beginning of British military evacuation from the twenty-six counties of the prospective Free State.

Perhaps the most evocative of these was the ‘surrender’ as the pro-Treatyites put it, of Dublin Castle, the citadel which housed the administration of British rule in Ireland.

The Provisional Government stated that it had ‘taken the surrender’ of Dublin Castle. The British that they had ‘duly appointed the Provisional Government.

The Provisional government released a statement saying that it had ‘received the surrender’ of the Castle on January 16 1922. The reality however was much less dramatic.

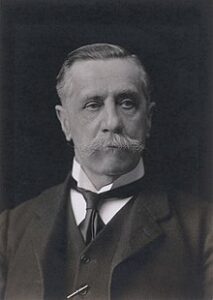

The British declared that Collins had met the Lord Lieutenant, Fitzalan and that the latter had ‘duly installed’ the Provisional Government and that the courts and public servants would ‘continue to carry out their functions’.[2]

Collins met Fitzalan in private to formally receive authority from the representative of the British monarchy, to ‘kiss hands’ in British theory.

Contrary to the impression created later, notably in the film ‘Michael Collins’, there was, as Maurice Walsh remarks, ‘no independence celebrations, sonorous speeches or hauling down of the Union Jack’ as would take place some 40 years later when Britain left many of her erstwhile colonies in Africa and Asia.[3] There was no pro-Treaty military involved, no formal lowering of flags and playing of anthems. Collins was there in civilian clothes and in a civilian capacity as chairman of the Provisional Government.

News footage of the day shows modest crowds cheering as Provisional government ministers arrive by taxi, stewarded by a Dublin Metropolitan policeman and apparently unarmed British soldiers.[4]

Tim Pat Coogan’s biography of Collins contains the famous anecdote that, having arrived seven minutes late, and being chided by British officials, Collins responded that ‘you people have been here for 700 years.’ But popular as this story has become, it is not clear where it comes from. Collins was indeed late, as a result of a railway strike between Longford and Dublin. But he was an hour and half late, not seven minutes, which at the least removes the quip attributed to Collins of its satisfying symmetry.[5]

The main practical purpose of the exercise was to acquaint Collins and his Ministers in the Provisional Government with the heads of Department of the Civil Service, all of whom would remain in their posts at the Castle in the new dispensation. Henry Robinson, the head of the civil service said that some ministers looked ‘pale and anxious’ but that Collins was ‘bonhomie itself’ evidently happy and eager to get the handover of power started.[6]

The Castle was not militarily occupied by Irish Free State forces until August 1922.

However, the Provisional Government based itself, not in the Castle, but first (briefly) in the Mansion House and then in City Hall (adjacent to the Castle) on January 21. The latter, not the Castle was the first British military post vacated in the city. Beggars Bush became the first barracks in Dublin to be handed over on February 2.[7]

The British commander Dublin, General Boyd, moved his Headquarters from the Castle to the barracks in the Phoenix Park in January 1922, but it was not until eight months later that Dublin Castle was fully militarily handed over to the Provisional Government.[8]

The papers of Richard Mulcahy the commander in Chief of the pro-Treaty National Army contain a correspondence between Alfred ‘Andy’ Cope, the Acting Chief Secretary for Ireland, and general Emmet Dalton on the handover of Dublin Castle on August 17 1922.

It appears that at this date it still had a Royal Irish Constabulary garrison, a force on the verge of disbandment, which was due to be replaced with units of the new Irish Civic Guard (later renamed the Garda Siochana).

By now Civil War was raging between pro and anti-Treaty factions. Cope noted that ‘it [the Castle] is vulnerable, overlooked at all points. If you don’t want to arm the Civic Guard in a military fashion, you should post the Army there’.

A reply came from Dalton on August 15. The (unarmed) Civic Guard was to take over, but three machine gun posts, to be manned by the National Army, were to be erected, under Dan Hogan, Officer Commanding, Eastern Command. There were called into action several times over the following weeks as the post was fired on numerous times by anti-Treaty forces.[9]

Dublin Castle was thus occupied by Irish Government forces, both police and military, not in the circumstances of optimism and hope of January 16, 1922, but amid the violence and bitterness of Civil War, on August 17 1922.

If the true story of the ‘surrender’ of Dublin Castle is much less dramatic than popularly perceived, this probably says something about the manner in which British rule actually ended in the most of Ireland. The British from their point of view, conducted a managed, staged withdrawal from a duly constituted Dominion. Their last military garrison only departed in December 1922 and many parts of the pre-existing civil service continued as before.

The remaining bloodshed and in-fighting was to be among the Irish nationalists themselves.

References

[1] The Treaty was approved in the Westminster House of Commons and House of Lords on December 16 1921. It was ratified narrowly in the Republican Second Dail on January 7. But as the British did not recognise the Dail, the House of Commons of Southern Ireland, the body created by the Government of Ireland Act 1920, had to be reconvened on January 14. It unanimously ratified the Treaty as those opposed to it did not attend.

[2] Dorothy Macardle, The Irish Republic (1968), p.593

[3] Maurice Walsh, Bitter Freedom, Ireland in a revolutionary World 1918-1923, p.333-334

[4] You can watch the British Pathe footage here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pgiDMzcxyPo

[5] A good account of the handover is here on the Dublin Castle website.

[6] Padraig Yeates A City in Civil War, .p. 29-30

[7] Ibid.

[8] McArdle, P.594

[9] Notes from Mulcahy papers: UCD P7/B/60