The Dead of the Belfast Pogrom – Addendum

By Kieran Glennon

Introduction

Since the original The Dead of the Belfast Pogrom article was written, further research has been carried out which allows a more refined picture to be painted regarding the fatalities due to political violence in Belfast from 1920-22.

Most of this additional detail comes from the press reports of the City Coroner’s inquests held to establish the causes of deaths.

These provide more definitive evidence of the circumstances in which people were killed and, in some cases, highlight killings which had originally gone unreported by newspapers – by the later stages of the conflict, the level of violence was such that the Coroner was forced to conduct inquests in batches, so searching for an inquest report for one particular killing could sometimes lead to discovery of an entirely new fatality. So far, press reports of inquests or the proceedings of military courts of inquiry have been identified for 85% of those killed.

With this new evidence, the total of fatalities has increased by one to 499 but within that number, there are a number of movements in terms of people and locations. An updated chronology listing all those killed is available here.

Killings added to the chronology

Alfred Phippin was shot by a sniper in North Thomas Street off York Street on 23rd November 1921 and died on 2nd December – his initial wounding was reported in the press but not his subsequent death. The inquest into his killing was one of eight held together on 11th January 1922.[1]

The most recent count lists 499 victims of political violence in Belfast in 1920-22, not counting those who died in conflict related accidents or suicides.

The cases of Henry Gallagher and Henry Corrigan illustrate the perils of using press reports on incidents as a source. Henry Gallagher from Little Patrick Street, also off York Street, was included by the Belfast News-Letter in a list of ten deaths that occurred on 14th February 1922.

However, on the same day, another Belfast paper, the Northern Whig, reported that Henry Corrigan of 22 Little Patrick Street had been shot dead in nearby Great George’s St. Gallagher’s death is included in G.B. Kenna’s Facts & Figures of the Belfast Pogrom 1920-22 and in Alan Parkinson’s Belfast’s Unholy War; Corrigan’s is included in neither.

In the Northern Whig report of an inquest held on 1st March, Corrigan’s address was given as 20 Great Georges St. The two names are similar, although they have different addresses; while the Northern Whig reporter may well have confused the location of the incident for Corrigan’s residence, he is now treated as an addition to the chronology.[2]

The case of John Hunter is similar to that of Phippin. Hunter was reported as having been wounded in Cupar Street in Clonard on 19th February 1922. He died in the Mater Hospital later that night but this went unreported. His inquest was one of seven held together on 20th April.[3]

The killing of Patrick McGuigan illustrates the perils of relying solely on Belfast papers as sources – none of the four were published between 21st July – 21st August 1922 due to a printers’ strike. McGuigan was shot and wounded while working on slob-land in Ballymacarrett on 8th August, during the strike.

A chance discovery of a clipping from the Irish Independent in an RUC file on an unrelated incident first drew this author’s attention to McGuigan’s wounding, further investigation revealed his death three days later.[4]

William Kinsella is the final new addition, another man whose killing initially went unreported. The press report of his inquest, one of two held that day, revealed that he was killed by a sniper in the same Great George’s Street off York Street on 17th September 1922.[5]

Killings removed from the chronology

Four killings have been removed from the chronology: two because they didn’t actually happen, one due to double-counting and one as a result of re-classification.

The first week of September 1920 was a confusing one in relation to British military casualties. On 2nd September, Lance-Corporal Harold Green was shot and wounded in Sultan Street in the Lower Falls. On 4th September, according to Kenna and to Belfast historian Joe Baker, a Private Charles Harold died in a military hospital as a result of wounds previously received. The original chronology assumed that Kenna and Baker had got the name wrong and that it was Lance-Corporal Green who had died.

Four killings have been removed from the chronology: two because they didn’t actually happen, one due to double-counting and one as a result of re-classification.

However, Eunan O’Halpin and Daithí Ó Corráin’s The Dead of the Irish Revolution has since brought to light the death of Sergeant Percy Harold Charles Turner. As noted in his death certificate, he died in a Belfast military hospital on 4th September after gangrene had set into a leg wound.

The revised conclusion is that of these three soldiers with Harold in their names, only one died. Lance-Corporal Harold Green, happily for him, survived so his name has been removed. Kenna and Baker now appear to have conflated Private Charles Harold with Sergeant Percy Harold Charles Turner; the latter’s death is recorded as an accident by www.cairogang.com and as accidental deaths are not included in the chronology, neither is his.[6]

The case of Eugene Kelly reveals the dangers of trusting initial press reports of killings. Various papers reported those of John Kelly and Thomas Thompson in Ohio Street near the Crumlin Road on 24th November 1921; a number of sources reported that Eugene Kelly, a brother of the dead man, died the next day. Eugene Kelly was therefore included in the original chronology.

However, O’Halpin and Ó Corráin state that Eugene Kelly’s death was “erroneously reported.” Further investigation revealed that on 29th November, the Irish Independent said that he was “…not dead. He is ill and his illness was aggravated by the news of his brother’s death.” Eugene Kelly’s name has therefore been removed.[7]

On 21st November 1921, a man was shot dead in Earl Street off York Street. He was initially identified in press reports as Andrew James Stewart, a resident of nearby Nelson Street, so he was included under that name in the chronology.

Other reports stated that a man named Andrew James had been killed in the same street on the same day, so he too was included. As this is a case of double-counting on the part of the author, and as Andrew James was the name given at the inquest, Andrew James Stewart has been removed.[8]

During the pogrom, several people were killed as a result of being hit by police or British military armoured cars during rioting. Various sources reported that on 13th July 1922, Robert Boyd had “Died after being crushed under an RUC Crossley tender during disturbances on the Newtownards Road”.

On this basis, he was included in the chronology. However, the report of his inquest held several days later reveals that Boyd had been running for a tram when he was knocked down by a vehicle which was “…a military touring car, and had a distinguished officer as passenger.” No reference was made to any rioting having been going on at the time. As Boyd’s death was clearly the result of a traffic accident rather than being conflict-related, his name has been removed from the chronology.[9]

Other accidental deaths not included

During the additional research, three more deaths came to light, although as these were accidental, they are not included in the revised total of 499.

I have counted eleven accidental conflict-related deaths: one Fianna member, two British Army soldiers, one RIC officer and seven civilians, which would bring total conflict-related death toll in Belfast up to 510.

On 28th June 1921, an inquest was held into the death of a man who had not yet been identified. He had been arrested for a curfew violation on 19th June but while being transported to a police barracks, he jumped from the RIC Crossley tender and sustained head injuries from which he subsequently died.

Joe Devlin, MP for Belfast West, raised the incident with the Chief Secretary for Ireland in the House of Commons at Westminster, asking him whether the dead man was in fact named Edward Fitzgerald; Devlin was told that betting papers with the name “Edward Fitzgerald, commission agent” had been found on the man. He is included under that name in The Dead of the Irish Revolution.[10]

If accidents are counted the death toll in Belfast climbs to 510.

Sergeant Eugene Ahern of the RIC was killed accidentally on 15th February 1922: a Special Constable was cleaning a Lewis gun in Springfield Road barracks when it went off, fatally wounding the Sergeant.[11]

Another accidental shooting happened on 24th September 1922 when a four-year-old boy was killed. John McGuigan’s parents were at a party in Bond Street in the Market area; Special Constable William Mawhinney, who was known to the hosts of the party, came into the house shortly before 2:30am – joking that “You need not be afeared. There is none in the spout, but there soon will be one in,” he raised his rifle towards the ceiling and it went off.

At that instant, a woman in the room upstairs was passing the child to his father – the bullet came through the ceiling, grazing the woman but killing the boy. Mawhinney was subsequently charged with murder but pleaded guilty to manslaughter, for which he was sentenced to six months’ imprisonment with hard labour.[12]

Amendments to status of those killed

The status of eight of those killed has been changed.

Six men previously described as Protestant civilians are now classed as combatants – members of the Imperial Guards. This was a loyalist paramilitary organisation initially founded in August 1920 by members of the Ulster Ex Servicemen’s Association and recruited mainly from among the shipyard workers. It was revived in early November 1921 following the de-mobilisation of the B Specials under the terms of the Truce.[13]

Six men previously described as Protestant civilians are now classed as loyalist paramilitaries and two Catholics as republicans.

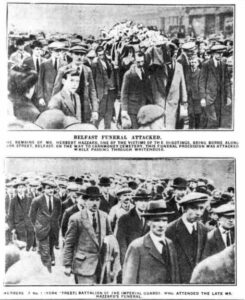

A press report on the joint funeral of Andrew James, mentioned above, and Bertie Phillips, killed on 23rd November 1921, noted that the pallbearers were provided by the Imperial Guards. Similarly, companies of the Imperial Guards formed part of the corteges in the funerals of David Cunningham, killed on 22nd November, and Alex Reid, killed eight days later. The entire York Street Battalion of the Imperial Guards took part in the funeral processions of Walter Pritchard, killed on 17th December, and Herbert Hazzard, killed on 8th March 1922.[14]

Funerals of other Protestant victims of the violence were reported on, but with no mention made of Imperial Guards participating – so their presence was the exception rather than the rule.

The implication is that they only attended funerals of members who had been killed. Press reports or a photograph of an IRA presence at funerals were previously accepted as evidence of IRA membership; similar weight is now being given to the evidence of these six men’s membership of the Imperial Guards.[15]

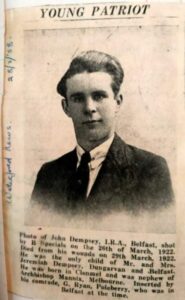

John Dempsey was killed on 26th March 1922 at Mountcollyer Avenue off North Queen Street. His mother heard knocking at the family’s front door, looked out and saw two men, who then left; one of the men returned, armed, but went away again so Dempsey went to take refuge in a neighbour’s house.

Minutes later, his mother heard shots and found her son lying in the neighbour’s hallway. Dempsey had been classed as a Catholic civilian until a press clipping was sent to the author: this was a memorial, inserted in a Waterford paper in 1958, stating that Dempsey had been an IRA member who was shot and killed by B Specials. Although no Military Service Pensions Collection (MSPC) file on Dempsey has yet been released, it seems improbable that anyone would fabricate such a claim almost forty years later. On that basis, he has been re-classified as an IRA member.[16]

Similarly, James Smith, killed on 18th April 1922, has been re-classified from Catholic civilian to a member of Na Fianna. Although no MSPC file on him has yet been released either, he is almost certainly the same person commemorated on the Republican movement’s County Antrim Memorial in Milltown Cemetery as J.P. Smyth, killed on 18th April 1922.

Amendments to locations of killings

Two sets of significant changes were made to the locations of the killings.

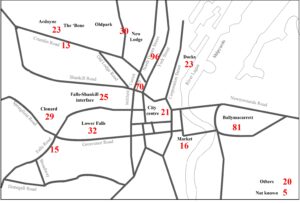

Firstly, arising from work done on a separate project, it became clear that an overly restrictive definition of the Market area had been used in the original database, one which does not match that used by residents of the district. As a result, the Market is now shown separately in its own right, with sixteen killings having happened there.

Secondly, based on the evidence presented at inquests, the precise locations of several killings previously classified as “Not known” can now be established. In addition, locations given in some initial press reports and used in the original database have been corrected. Altogether, twenty-three such amendments were made.

Summary and conclusions

The most notable outcomes of the latest research are that the total of those deliberately killed in political violence in Belfast from July 1920 to October 1922 now stands at 499, and that members of a loyalist paramilitary organisation have now been identified among those killed.

But despite these changes, the key conclusions are the same.

Although one British soldier has been removed and eight people previously identified as civilians are now noted as being combatants, the fact remains that civilians bore the overwhelming brunt of the violence – they make up 86% of those killed (427 people), while combatants on both the unionist and Republican sides account for only 14% (72 people).

Civilians bore the overwhelming brunt of the violence; 86% of those killed, while combatants on both the unionist and Republican sides account for only 14%.

Females were the victims of political killings in Belfast to a far greater degree than elsewhere in Ireland. They make up 4% of the total killed nationally according to The Dead of the Irish Revolution, but 15% of those killed in Belfast. Within Belfast, 74% of the women and girls killed were Catholic – this points to a concentration of the violence in areas where Catholics lived.[17]

The original article highlighted the fact that fatalities were highest in the north of the city, particularly in the area around York Street and North Queen Street. The refinements allowed by the inquests evidence show that this is even more the case now – 96 killings, or almost a fifth of the Belfast total, happened in that area alone.

In terms of presumed political affiliations, nationalists suffered a hugely uneven share of the violence. They accounted for 24% of the Belfast population in the 1911 Census, but 57% of those killed during the pogrom period – more than double their share of the city population. The violence of 1920-22 was therefore directed at them to a massively disproportionate degree.

References

[1] Northern Whig, 24th November 1921 & Belfast Telegraph, 12th January 1922.

[2] Belfast News-Letter, 15th February 1922; Northern Whig, 15th February & 2nd March 1922; G.B. Kenna, Facts & Figures of the Belfast Pogrom 1920-22 (O’Connell Publishing, Dublin, 1922), p166; Alan Parkinson, Belfast’s Unholy War (Four Courts Press, Dublin, 2004), p226.

[3] Belfast News-Letter, 20th February 1922; Northern Whig, 20th February & 21st April 1922.

[4] Internment of Thomas James Donnelly, Lagan St, Belfast and 29 others, Public Record Office of Northern Ireland, HA/5/961V; Irish Independent, 9th August 1922; Derry Journal, 14th August 1922.

[5] Belfast News-Letter, 20th September 1922.

[6] Belfast News-Letter, 4th September 1920; Kenna, Facts & Figures, p160; Joe Baker, The McMahon Family Murders (Glenravel Publications, Belfast, 2003), p49; Eunan O’Halpin & Daithí Ó Corráin, The Dead of the Irish Revolution (Yale University Press, London, 2020), p173; https://www.cairogang.com/soldiers-killed/turner-ph/ph-turner.html; https://www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead/casualty-details/401621/p-h-c-turner/. In the unlikely event of the author ever having a son, he will definitely not be named Harold.

[7] Irish Independent, 26th & 29th November 1921; Kenna, Facts & Figures, p165; Baker, McMahon Family Murders, p61; Parkinson, Belfast’s Unholy War, p170; O’Halpin & Ó Corráin, Dead of the Irish Revolution, p538.

[8] (Andrew James Stewart) Northern Whig, 22nd November 1922; Kenna, Facts & Figures, p164; Baker, McMahon Family Murders, p59; Parkinson, Belfast’s Unholy War, p168; (Andrew James) Belfast News-Letter, 25th November 1921; Belfast Telegraph, 3rd December 1921; (inquest) Belfast News-Letter, 5th January 1922.

[9] Northern Whig, 14th July 1922; the quotation is taken from Baker, McMahon Family Murders, p78; Parkinson, Belfast’s Unholy War, p301; Northern Whig 18th July 1922.

[10] Northern Whig, 29th June 1922; Belfast Weekly Telegraph, 16th July 1921; O’Halpin & Ó Corráin, Dead of the Irish Revolution, p472.

[11] Northern Whig, 24th March 1922.

[12] Northern Whig, 27th September 1922; Belfast Telegraph, 23rd & 25th November 1922

[13] Michael Farrell, Arming the Protestants – The Formation of the Ulster Special Constabulary and the Royal Ulster Constabulary 1920-27 (Pluto Press, London, 1983), p28; Northern Whig, 14th November 1921.

[14] Belfast News-Letter, 25th November, 5th & 21st December 1921; Northern Whig, 28th November 1921 & 13th March 1922.

[15] For example, Murtagh McAstocker; his MSPC file has been released since the original article was written – see: Murtagh McAstocker, MSPC, Military Archives, DP6618.

[16] Northern Whig, 29th April 1922; Waterford News, 28th March 1958 – the author would like to thank Colum O’Rourke for sharing this information.

[17] O’Halpin & Ó Corráin, Dead of the Irish Revolution, p12.