Fight for a Pension; John O’Sullivan’s fight for recognition

By Martin Harkin

Martyrdom is held most dearly in Irish Republicanism. From Wolfe Tone to Bobby Sands, hundreds if not thousands of names are commemorated on memorials, GAA grounds, bridges and train stations across Ireland. Robert Emmett, the Manchester Martyrs, and the signatories of 1916 are all remembered in ballads and poems.

Yet there are two young men who have been largely forgotten in Ireland until recently.

This fact is all the more ironic when you consider that their fateful actions set in motion a serious of furious demands from the British Government to the newly formed Irish Free State in Dublin that resulted in the outbreak of the Irish Civil War on 28 June 1922. These two men were Joseph O’Sullivan and Commandant Reginald Dunne O/C Irish Republican Army in London.

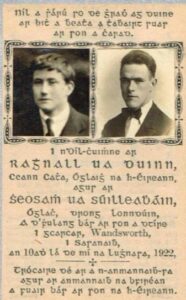

Dunne and O’Sullivan were two London-born veterans from the Great War who became actively involved in the struggle for Irish independence in the heart of the enemy capital. For their role in assassinating Field Marshall Sir Henry Wilson on the steps of his Belgravia home on 22 June 1922, Dunne and O’Sullivan were found guilty and sentenced to death at the Old Bailey.

Reginald Dunne and Joseph O’Sullivan were hanged for the assassination of Sir Henry Wilson in August 1922.

They met their end together on the gallows of Wandsworth Prison on 10 August 1922. There is no doubt the fates of the condemned men were overshadowed by the war in Ireland split in the Republican movement and ensuing Civil War.

Like most casualties in war, it is those forgotten families at home who are left to pick up the pieces of their lives. A previous article detailing Reginald Dunne’s mothers’ fight for financial and political recognition for her son can be found here Mary Dunne, a Mother’s Struggle for Recognition – The Irish Story. This article highlights the battle of John O’Sullivan to gain official recognition of his son Joseph

Family Traditions

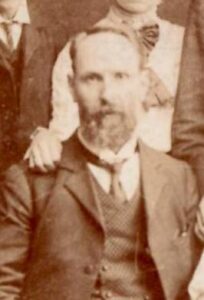

It is no surprise that Joseph became involved in the Irish struggle in London. His father John was well versed in the Fenian tradition. John O’Sullivan was born in Bantry, Co. Cork in June 1858, a mere decade after the Great Hunger ravaged the Irish countryside.

As a young man, John and his brother were forced to flee Bantry after a dispute with the local Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC).

This was during the upheaval of the Land War and it is possible that the two men were caught up the turmoil. Whilst his brother headed for safety in America John settled in London and became a successful tailor. John married fellow Cork woman Mary Murphy. Together they had thirteen children, eleven of whom survived into adulthood. Joseph was born 25 January 1897.[1]

Joseph O’Sullivan joined a unit of the British Army in 1915 which was associated with the Redmondite National Volunteers.

Joseph attended the prestigious St Edmund’s College in Ware, Hertfordshire. He was very pious in his Catholic faith. It is believed by O’Sullivan’s descendants that he had aspirations to become a priest.

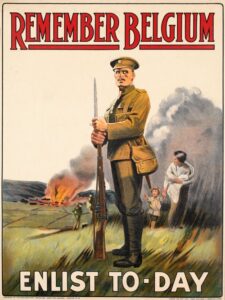

Following the outbreak of the Great War the German invasion of Belgium was quickly seized upon by the British media and became widely known as the Rape of Belgium. Reports of mass killings, destruction of towns and villages and the forced displacement of Belgian civilians caused outrage not just in Britain but throughout the world. It is quite possible that such emotive propaganda influenced many Irishmen in London and in Ireland to enlist in the British Army in order to save neutral Catholic Belgium from destruction.

In his witness statement to the Bureau of Military History, Richard Connolly, the London representative on the Supreme Council of the IRB (1914 – 1915) recorded that prior to the outbreak of war, the Irish Volunteers numbered approximately 1,000 in London.

In his witness statement to the Bureau of Military History, Richard Connolly, the London representative on the Supreme Council of the IRB (1914 – 1915) recorded that prior to the outbreak of war, the Irish Volunteers numbered approximately 1,000 in London.

Following the split in the Volunteer movement in September 1914 following John Redmond’s call for the organisation to join the British war effort, the majority of his company followed suit and enlisted. Connolly stated that there were only about 200 men remaining in the company.[2]

It is not clear whether or not Joseph O’Sullivan was a member of the Volunteers in 1914. However, given the circles that he moved in, it can be argued that Joseph O’Sullivan was one of thousands who enlisted in the British military as a result of Redmond’s appeal. He may also, however, have simply been caught up in the war-fever of 1914 or like many young men seen war as a great adventure that he wanted to see.

What is certain is that on 25 January 1915, Joseph’s 18th birthday, he joined the 8th Battalion, Royal Munster Fusiliers. This new service battalion was assigned to the 16th Irish Division, and was reserved for recruits from Redmond’s National Volunteers, which indicates that this was the background Joseph came from as well.

O’Sullivan lost a leg while serving at the front in France in 1917. When he was demobilised he faced a very different Irish political environment.

In August 1915 Joseph transferred to the 3rd Battalion, City of London Regiment. By 1917 O’Sullivan had reached the rank of Lance-Corporal and was severely wounded in the leg whilst serving in France, causing it to be amputated.

John’s daughter Margaret was active in Republican circles in London. In his witness statement, Gerald Doyle recalls how Margaret and a friend named Mary O’Byrne were waiting one day at a London train station to greet newly released Irish prisoners captured in the aftermath of the 1916 Rising. As Margaret waited on the platform several Red Cross trains arrived at the station carrying wounded military personnel returning from France.

As the stretchers were disembarking, Margaret recognised one of the soldiers as her brother Joseph. Up until this moment, the O’Sullivan family has no knowledge of his injuries.[3] He remained on the regimental roll until his discharge before the war’s end, receiving the Victory Medal and British War Medal.[4]

He was not only member of the family to serve in the Great War, as his brothers Patrick, Aloysius, Dennis and John were also involved in the conflict. Aloysius served together with Joseph in the 3rd Battalion, London Regiment before he was discharged with shellshock. Patrick served in the same regiment but with the 6th Battalion.

At one point he founded himself stranded in no-man’s-land on the Western Front following a devastating gas attack and was left for dead before being rescued. Dennis fought with the Australian Imperial Force, and John served with the Royal Engineers. Another brother, Eugene O’Sullivan did not see action but served with British military intelligence, focusing on the development of submarine programmes at the Vickers Yard in Barrow in Furness. It is worth noting that Eugene’s occupation as an agent with the Secret Service was listed on his daughter’s birth certificate.[5]

After being discharged, Joseph was fortunate to find employment with the Ministry of Munitions before working for the Ministry of Labour. It was about this time that O’Sullivan enlisted in the newly reorganised Irish Volunteers in London, alongside Reginald Dunne.

More than 200,000 Irishmen served in the British military during the First World War. Those who were not conscripted enlisted for varying reasons such as money, adventure, a sense of patriotic duty. O’Sullivan and many the thousands of National Volunteers who served did not lose their proud sense of Irish identity or nationalist aspirations. Moreover, many Irishmen joined the British Army as unwilling recruits, who faced the option of enlisting or being imprisoned.

The political landscape in Ireland had changed irrevocably from when Joseph enlisted in 1915 and his discharge in 1918. The Easter Rising and British reaction in its suppression and executions of the leaders saw Irish popular opinion swing dramatically from Home Rule aspirations to demands for a full and free Republic. In London the reorganisation of the Irish Volunteers was in full swing. Many Irish veterans like Dunne and O’Sullivan views had been radically altered by these events, in addition to their wartime experiences; they became more militant and radical in their views.

IRA career

During this period the Ministry of Labour was located in Montagu House which was located close to Scotland Yard, ideal for intelligence gathering. Dennis Kelleher believed that Dunne and O’Sullivan were founding members of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) in London.

The O’Sullivan home and tailor’s shop became a regular haunt for Irish men and women in London. It was an extremely useful link between Republicans travelling between London and Cork.

Patrick O’Sullivan served at one point as the Vice-Commandant of the IRA in London before moving to Cork No.1 Brigade where he continued to see active service.

Joseph joined the IRA after the war. His brother Patrick ended up with Cork No 1 Brigade.

Joseph was a highly dedicated Volunteer in the Republican movement in London. There are several accounts of his presence and involvement at the execution of the spy Vincent Fovargue, an IRA informer from Cork, who had fled to London after he was uncovered and whose corpse was discovered, attached with an IRA warning, on a Middlesex golf course. Rex Taylor names Joseph as being the man who pulled the trigger in Fovague’s killing.[6] By the time of his arrest, Joseph was Battalion Intelligence Officer of the London IRA. [7]

John received a final letter from his son that read “Keep your trust in God, dearest father and although I die in the eyes of the country a felon, remember the felon’s cap is the noblest crown an Irish head an [sic] wear. And how many of our noble countrymen have gone before the way as Reg [sic] and I?[8]

Three tragedies struck the O’Sullivan family within the space of two years prior to Joseph’s execution in August 1922. His mother Mary had died unexpectedly in 1920 and his brother John was fatally injured in March 1922 whilst working on the railway.

Claim for pension

It was more than ten years after Joseph O’Sullivan’s execution for the assassination of Henry Wilson that the family managed to apply for an Irish military pension.

The fledgling Irish Free State had legislated for the award of pensions under the Military Service Pensions Act, 1924. This was however, extremely narrow in its framework. There were strict stipulations in place for applicants, depending on their date of active service.

Furthermore women and anti-Treaty veterans were also deemed to be ineligible. John O’Sullivan was also unable to apply for any financial support from Dublin.

The political landscape in Ireland changed dramatically in the next decade as Éamon de Valera swept to power with Fianna Fáil with in 1932. On 23rd February 1933 John O’Sullivan sent a letter to Sean T. O’Kelly, Vice-President of the Executive Council of the Irish Free State.

He repeated the words of Reginald Dunne’s mother Mary, who wrote in her pension application of her understanding that should anything happen to Joseph and Reginald on active service, their parents would be looked after. John further pushed the notion that this promise came directly from Michael Collins.[9]

The O’Sullivan family in claiming an Irish military pension were insistent that the shooting of Field Marshal Wilson was done on the orders of Michael Collins.

Many believe that the order to assassinate Sir Henry Wilson came directly from Collins. Peter Hart argued that a list of targets for assassination was compiled before and during the Treaty negotiations, and that all assassination orders were signed off by the Director of Intelligence, Michael Collins.[10]

Mary Dunne was visited by two senior Free State army officers Tom Cullen and Liam Tobin who handed her the deeds to her rented house in Bray, Co. Wicklow. Cullen and Tobin were loyal lieutenants to Michael Collins, and the fact that they personally visited Mary Dunne and gifted her a house suggests that they did so in order to unofficially acknowledge the actions of her son Reginald and Joseph O’Sullivan. Both John O’Sullivan and Mary Dunne stressed in their pension applications that their sons were promised that the Republican government would look after their families should anything fatal occur.

John’s letter to O’Kelly shows that he was a proud man who had worked hard his entire life and had never previously sought any help. Now however he was widowed and succumbing to old age, and was finding life increasingly difficult.

He referenced that fact that Mary Dunne had received the deeds of her rented house from senior Free State army officers, further alluding to the fact that this was unofficial form of compensation for the loss of her son Reginald.

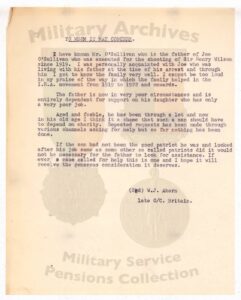

In the application, John declared that he had received £2 a week from Joseph up until his death, which was supplemented by 20s weekly pension. By 1933, John’s declared income was 40s a week. He received support in the form of statements and documents from a host of veterans of the IRA in London. One in particular came from Billy Ahearne, who declared that had Joseph “…not been the good patriot he was and looked after his job same as some other so-called patriots did it would not be necessary for the father to look for assistance.”[11]

O’Sullivan was turned down for a pension until the election of the Fianna Fail led government in 1932.

In a further letter dated 24th March 1933, John O’Sullivan wrote that he had read in the Irish Press that the government was prepared to help those who lost loved ones in the fight for freedom. O’Sullivan stated that “…my son Joe, who gave his young life for the great cause, a promise had also been given to him at that time that if anything happened him I would be looked after, but that has not been carried out.”[12]

In further correspondence to Sean T. O’Kelly, O’Sullivan wrote that “…it is with great reluctance that I am asking you to use your good offices to put forward my claim…” before adding in reference to the electoral victories in Éamon de Valera’s Fianna Fail in 1932 and 1933; “…hearty congratulations to our President [de Valera] and yourself on Ireland’s great victory.”[13] He went on to say of Joseph, that “we mourn his loss very deeply but at the same time we are very proud of his action as he removed a dirty orange dog”. John’s request for a pension was denied on 15th May 1933.

Not to be put off, he dutifully set about putting together another claim and received support from several prominent men who had been active with the IRA in London during the war. In a letter dated 12th May 1939, Sean McGrath, a one time London IRA Intelligence officer, submitted a letter to support John O’Sullivan’s claim. McGrath recalled how Reginald and Joseph “…carried out the legal orders from Headquarters of the Executive to execute a man already sentenced to death.”

He further claimed to know as a matter of fact that Collins gave the order to shoot Wilson along with the names of two other condemned men prior to the Treaty split.[14]

He further claimed to know as a matter of fact that Collins gave the order to shoot Wilson along with the names of two other condemned men prior to the Treaty split.[14]

McGrath referenced a speech from De Valera in New Ross, 14th August 1936, where he stated that ‘the Volunteers became the army of the Republic, under the control of the elected Government of the Republic.’ In McGrath’s eyes, the order from GHQ was also an order from the Irish Government, and ought to be recognised as such.[15]

John O’Sullivan was now aged 81 and unable to leave the house. McGrath’s letter asks what a consolation it would be for his son and Reginald to be “recognised as worthy soldiers of the Irish Republic who died bravely as soldiers.” McGrath went further in his statement, claiming that “Dunne and O’Sullivan carried out the orders for this execution from Dublin HQ – to execute a man who had been sentenced to death…I know for a fact that the order for the executions (as well as for that of two others) was given by Michael Collins prior to the Truce, and it was confirmed while the Treaty negotiations were in progress.”

Sean McGrath, a London IRA intelligence officer, stated that Dunne and O’Sullivan: ‘carried out the legal orders from Headquarters of the Executive to execute a man already sentenced to death.”

McGrath also referenced the tremendous piety of the condemned Volunteers, adding that if there had been any doubts as to the legality, they would not have carried out such an order. He added that “I therefore contend that in carrying it out the decree of the IRA Executive, Dunne and O’Sullivan were carrying out the decree of the Executive Government of the Irish Republic.”

A statement was published by the Association of Old IRA and Cumann na mBan in London supporting McGrath’s assertion. It was signed by Patrick O’Sullivan, Joseph’s brother and Chairman of the association, together with F. Lee, secretary. It is important to clarify McGrath’s reference to the ‘IRA Executive’. When they withdrew the allegiance of the army from the Dáil, the Anti-Treaty IRA reaffirmed their oath to the Irish Republic and the newly established IRA Executive. In McGrath’s case, his quote refers to the Executive of the Provisional Government of the Irish Free State.

McGrath had served as Intelligence Officer in London and was chiefly responsible for the procurement of arms and ammunition. In addition, McGrath was Secretary General of the Irish Self Determination League, dubbed the ‘most powerful Irish organisation that ever existed’ in Britain.[16] During the Civil War he took the Anti-Treaty side but remained fond of Michael Collins, his former IRB chief. In Frank McGuinness’ eulogy to McGrath in the Irish Press, it was recalled how Collins and Brugha often stayed at his home when they were in London

Pension granted

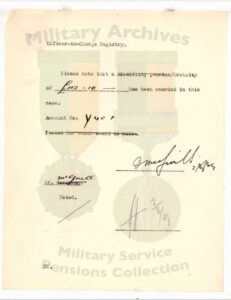

On 12 July 1939, after six long years of letters and endless correspondence with Dublin, a recommendation was made that the now 84 year old John O’Sullivan be awarded a gratuity of £112/10s, the maximum sum available to him under the legislation.

On 12 July 1939, after six long years of letters and endless correspondence with Dublin, a recommendation was made that the now 84 year old John O’Sullivan be awarded a gratuity of £112/10s, the maximum sum available to him under the legislation.

However, there was a substantial delay in awarding the sum, and it had still not been received by the outbreak of the Second World War. Patrick O’Sullivan wrote to the Board that his father was not fit to cope with the sudden air raid warnings, and that he wished to send his father back to his home place in Bantry in Co. Cork.

This persistence was finally rewarded and the O’Sullivan’s received word that the money would be received from 30th October 1939.

Despite receiving a gratuity, John O’Sullivan’s frailty and ill health led to sons Patrick and Eugene making a further request for financial assistance on their father’s behalf. In his correspondence to the Free State’s High Commissioner in London Patrick explained that much of the gratuity had been used to cover John O’Sullivan’s medical bills.

On 12 July 1939, after six long years, the now 84 year old John O’Sullivan was awarded a gratuity of £112/10s, the maximum sum available to him under the legislation

John required constant medical treatment and was unable to be left alone. In December 1936 John was diagnosed with a terrible case of bronchial pneumonia from which he never recovered.[17] As a result John required two nurses to care for him over for the following four months. As a result of rapidly deteriorating health, the family had to purchase a special air bed and an increased supply of fuel and lighting bills sent the cost spiralling. John suffered from a severe bout of pneumonia and as Patrick O’Sullivan stressed “Any medical man will confirm that…brandy is very essential for a long period to stimulate the action of the heart.” [18]

Eugene O’Sullivan wrote to explain that financial help did not add up to much. He noted how Patrick gave his father an occasional bottle of brandy, cigarettes and a few pieces of clothes totalling approximately £10. Eugene himself supposed that his own contribution amounted to £20, notwithstanding a small sum to cover the travel costs of another sister who looked after John while Kitty was at work.

Kitty herself paid the rent with 1 guinea a week, in addition to food, coal and gas. John’s 10s a week pension went to Kitty to help with the upkeep. Eugene summed up the issue with his elderly father when he stated that he and his brothers did all they could for their father but, as they were married with families and had their own problems and worries. Consequently, they were unable to help as much as they wanted to, and therefore required further help from the Free State.

He clearly outlined how any payment from the Irish Government would immediately be spent on covering these huge medical bills. On 20 April 1940 the Board declared that they were unable to recommend any further financial award due to the fact that the monetary aid received by John O’Sullivan from his family was too great to merit further financial awards. The Amy Pensions Board in Dublin ruled that John received £58 10s in financial aid from his family, well above the required £40 threshold necessary for further financial award.[19]

Proud to the end

John O’Sullivan remained a proud Irishman and a proud Republican until his death in 1942 at the age of 84. He fought for the remainder of his life to gain recognition for his son’s actions and persisted for six years to receive financial recognition on behalf of his late son.

John was just one of thousands of other veterans and family dependents who had to navigate through an excruciatingly tedious bureaucratic process. His own personal experience was not just confined to dealing with the Army Pensions Board. Endless letters were sent to and from various government departments, navigating their way through the finance branch of the Department of Defence, the Department of Posts and Telegraphs, the Department of External Affairs, and also the High Commissioners office in London.

John was just one of thousands of other veterans and family dependents who had to navigate through an excruciatingly tedious bureaucratic process

Despite any frustrations that John may have had regarding his claims, he remained immensely proud of the sacrifice that Joseph had made for Ireland. This is perhaps best highlighted when Joseph had just received his death sentence in 1922 in the Old Bailey.

The young man rose to address the court in the style of Robert Emmett, declaring to those present “What I did I did for Ireland, and for Ireland I am proud to die.” Upon hearing his son speak, John stood up to face the judge to declare that “My Lord, you can kill their bodies but you can never kill their souls, God save Ireland!”[20]

References

[1] Census ancestry.co.uk

[2] Richard Connolly,WS523, Military Archives Ireland

[3] Gerald Doyle, WS1511, Military Archives Ireland

[4] Joseph O’Sullivan military service record

[5] Family oral interview

[6] ‘Assassination: the death of Sir Henry Wilson and the tragedy of Ireland’ Rex Taylor.

[7] John O’Sullivan pension files

[8] Sligo Champion Saturday 19 August 1922

[9] John O’Sullivan’s pension files

[10] Peter Hart. “Michael Collins and the Assassination of Sir Henry Wilson.” Irish Historical Studies, vol. 28, no. 110, 1992

[11] Billy Ahearn letter supporting John O’Sullivan’s pension claim

[12] John O’Sullivan pension files

[13] John O’Sullivan letter to Seán T. O’Kelly

[14] Sean McGrath letter supporting John O’Sullivan’s pension claim

[15] Sean McGrath letter supporting John O’Sullivan’s pension claim

[16] Irish Press Monday 24 July 1950

[17] Military archive

[18] John O’Sullivan pension files

[19] Military archive

[20] John O’Sullivan pension files