Gloved sparring on the big stage: touring exhibitions of boxing in late nineteenth and early twentieth century Ireland.

In devotion to that durable fighter,

In devotion to that durable fighter,

that faithful companion, Jack Ashton.

By Ray Esten

A vibrant boxing scene existed in Ireland in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Various tournaments offered fight fans all the adrenaline and unpredictability that comes with competitive sports. Though the most admired of the heavyweights generally operated in England, continental Europe and particularly, America.

Yet, travelling sparring exhibitions by well-known heavy weights like, the sports first superstar John L. Sullivan, offered the general public in Ireland a unique experience, even if the entertainment was of a milder brand.

Exhibition matches formed part of a vibrant boxing scene in nineteenth and early twentieth century Ireland.

The general public may have overlooked the ‘exhibition aspect’ or perhaps they simply did not care. These exhibitions of sparring did not hurt the boxers’ profile either. Indeed, they fitted well into an evolved culture of leisure which followed the industrial revolution. Best illustrated by ‘football mania’’ which swept late Victorian England.[1] Subsequently, the exhibition served the boxer, who opened performances at the theatre (as they had a century earlier) and later the movie industry, an essential component to the boxer magnifico whose fistic career could be brief.

Interpretations: what was an exhibition?

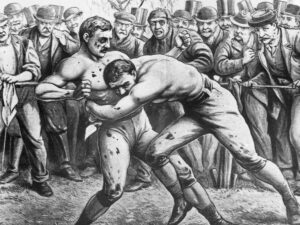

The Marquess of Queensbury’s rules, published in 1866, made boxing gloves a feature of the competitive sport. Nonetheless, bare fists or for that matter the gloved exhibitions of skill (which existed from the early days of the Prize Ring) remained part of fistic culture. Though bare fists were judged to be disorderly exhibitions and were forbidden in England by 1882, [2] while, The Law Journal noted that …’’two men may spar with gloves if the gloves are not a mere pretence.’’[3]

Though interpretations of what constituted a mere pretence or the word ‘exhibition’ could be ambiguous. In 1888, for instance, at the Queens Hotel Queenstown (Cobh) an event coordinator by a man named Professor O’Keefe presented a boxing exhibition and ‘assault at arms’, which incorporated gymnastics, fencing and Indian club workers (an excise of swinging clubs that was adopted from Hindu traditions).[4]

An advertised boxing exhibition might be instead a competitive boxing match in masquerade, to mislead the authorities.

This troupe or variety show offered a different type of entertainment, whereas an advertised boxing exhibition might be instead a competitive boxing match in masquerade, to mislead the authorities.

According to Elliot J. Gorn the gloved Era of boxing began when James J. or Jem Corbett defeated John L. Sullivan in New Orleans in 1892, in the view of a respectably dressed audience and with an undercard containing separate weight categories. And it was ‘’no more running from the law or not so much.’’[5]

The prize ring had reached semi-respectability. Take, for example a case before Bow Street magistrate court in London in 1894, which revolved around a struggle which resulted in the loss of life for one of the combatants. Serious charges of aiding and abetting against those who acted as seconds, and time keepers were undertaken. The defence in that case convincingly argued that everything had been done ‘on the basis of Queensbury rules’ and that the fight was only an exhibition of skill, and only for a small stake. The defendants were acquitted at the trial. [6]

Ireland and the celebrity touring exhibitions.

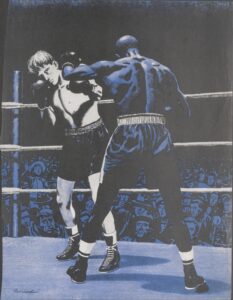

Whereas the touring exhibitions or sparring matches, which transpired in Dublin and other cities in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century solely took the form of demonstrations of skill. They featured, the big heavyweights like Sullivan, Jackson and later Johnson. These big names (usually the lead boxer) relied upon a skilled partner, who practiced a certain amount of restraint, while still displaying enough clever work to excite the audience. There were no points awarded and the matches were not generally full rounds or full durations.

The fact that it had few upsets discouraged the gambling element who historically congregated at prize fights. Yet, it had an aspect of chance (the gloves being skin tight) and particularly, when two antagonists met (the result of an exhibition was never recorded on a fighter’s record). On the whole though, the tours that visited Irish and other European cities appeared to be largely well scripted affairs.

This spectacle could be accompanied by wrestling or acrobatics. By the early twentieth century, a visiting fighter might partake in a few rounds with a local hero. Members of the audience were on occasion called upon to raise their fists. This offered an element of chance, though there were few takers. Other aspects of the boxer’s repertoire included skipping and of course ball punching. The scientific boxer dancing around the ball while delivering every variety of punch was of great interest.

Boxing royalty, Sullivan, Kilrain and Jackson

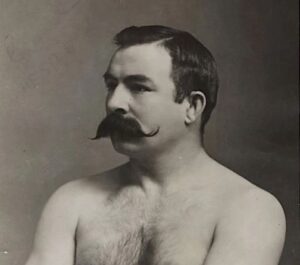

The most prominent fighter of the era was Bostonian John L. Sullivan (WHC 1882-1892) partook in a number of sparring exhibitions between 1883 and 1884, toured the states, ‘calling the house to fight’ or conducting an exhibition should that fail.[7]

This colourful character had Irish parents from Kerry and Athlone. The force of his character has been credited with substituting boxing gloves for the naked fist and the Marquis of Queensbury Rules for the London Prize Rules,[8] though, Sullivan fought with bareknuckle for most of his career.[9]

Changes under Queensbury rules included the wearing of gloves, removal of wrestling and rounds being three minutes with a minute’s rest.

Some of the most prominent boxer of the era were Irish Americans and many toured Ireland.

The Irish Examiner, announced in November of 1887 that Sullivan, his long-term sparring partner John ‘Jack’ Ashton, and a whole host of boxing and wrestling talent would be in Dublin that December. The Irish tour commenced at Leinster Hall and to the sound of great cheers[10] and the entertainers found themselves in the company of all classes.[11] Sullivan noted later that his reception in Dublin was …’’marvellously enthusiastic, and brought forcibly to my mind the fact that I was in the midst of the warm-hearted people who I am proud to claim descent. ‘’[12]

Just two months prior to this event a prize fight in Dublin, for £ 20 seen warrants issued for the pugilist’s arrests, as bare-knuckle fighting was illegal. Sullivan could surely empathise for he still fought with his naked fists. Yet, he enjoyed the indoor arena, well-lit (some by electricity) and in front of a crowd of middle-class patrons. It was a far cry from Sullivan’s days bare-knuckle scrapping on a barge on the Hudson River.[13]

Furthermore, his bruises had been rewarded with the ‘’ ten-thousand-dollar belt’’ of solid gold and studded with nearly 400 diamonds and issued to the ‘’Champion of Champions’’ (decorated with the Irish, American and English flags).[14]

Sullivan’s Irish exhibition, with the noted battler Jack Ashton, offered excitement and this was repeated in Waterford and in Cork where Sullivan sparred with (and roughed up perhaps) a local hero named Frank Creedon[15] before moving on to Belfast [16] then leaving the country, with in his possession, seventeen blackthorn sticks, four jugs of whiskey, and one Irish tweed suit. Sullivan later claimed to have made more money in one week in Ireland than in his entire time in England.[17]

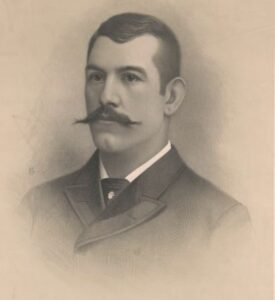

The ‘Police Gazette ‘diamond belt holder (rival belt) Jake Kilrain (also of Irish descent) arrived in Dublin city in January of 1888. His belt had been issued by his promoter Richard Kyle Fox, a Dubliner by birth, and the owner of the influential sporting ‘National Police Gazette’[18] (the name reflects its original readership which observed the criminal world).

The presence of Kilrain does not seem to have attracted the eye of the social elites. His exhibition at Dublin’s Star Music Hall, it was said ‘’contained no one of prominence and there were no speeches made.’’ Instead, they at once got to business. Remarkably, Kilrain had recently fought the champion of England Jem Smith to a draw in what was a 106-round battle in France.[19] The notoriety of this event may have discouraged the professional classes. Nonetheless, Kilrain and his trainer Charles Mitchell displayed great skill, ‘’…fighting three two-minute rounds. Both drew frequent applause by clever stopping and getting away.’’

The crowd’s excitement caused an enormous crush, the venue being crammed from floor to ceiling. The doors closed on the crowds who waited outside for a glimpse of Kilrain and Charles Mitchell who was also of Irish stock.[20] and was about to go into training for a fight against John L. Sullivan. [21]

That Christmas was tainted by the scandal resulting from the exposure of the extra marital affair between the leader of Irish nationalism, Charles Stewart Parnell and his mistress Kitty O’Shea. A scandal which caused a bitter split in Parnell’s Home Rule Party and provided the topic of conversation at many a dinner table. A distraction from the political turmoil was provided by an extraordinary exhibition in Dublin by ‘the black prince’ Peter Jackson who had won the Australian heavyweight championship in 1886.

The Sportsman claimed that his reception rivalled that of John L. Sullivan. It was said that the admirers included ‘a multitude of the great unwashed’. Yet, contrasting with Kilrain’s exhibition in that it attracted Queens councils and Castle officials.

What was more, a mix up in the newspapers only added to the intrigue. Rumours spread that Jackson would ascend Nelsons Pillar. Better still, he had betted a thousand pound on himself to do it. Jackson’s biographer Bob Petersen said the people expected him to ascend the outside like King Kong. However, the thousands that congregated on O’Connell Street had to make do with Jackson walking its 167 steps.

The next night (Christmas Eve) Jackson offered 20 guineas to any man at the Leinster Hall who could stand before him. The challenge was taken up by a 20-year-old Peter Maher. The young fighter encountered Jackson’s infamous one-two punch. What Jem Corbett described as the most effective he had ever seen.[22] The mismatch was stopped in the second round and Sport called the affair one of the most humiliating spectacles that any Dubliner had ever witnessed.[23] Jackson travelled to America soon after in the hope of fighting John. L Sullivan.

The late nineteenth and early twentieth century

Boxing had undergone many changes under Queensbury Rules, most of which had only started to take effect.

Neverthless the appetite for exhibition sparring remained in good stead, and it is no wonder a large crowd assembled in Dublin to witness a boxing exhibition match between Frank ‘’Paddy’’ Slavin, described as the Australian champion of the world and the English champion, the same, Charles Mitchell.

The Belfast newsletter noted that many of the fans were deeply interested in the ‘scientific display’ on offer. The admission to the platform was 10s and the Belfast newsletter was astonished that such numbers paid the sum.[24]

Some fans were attracted by the prospect of bloodshed, but others wanted to see the ‘scientific display’ of boxing.

This was a pittance in comparison to black-market prices for tickets when Slavin met his nemeses Peter Jackson in London some fifteen months later. Tickets for that fight were said to have fetched as much as £ 25 each.[25] The exhibition in this period had not rivalled (in terms of financial gain) an actual competitive fight but, it proved lucrative nonetheless.

Peter Maher, the young boxer humiliated in the Leinster Hall, had developed as a fighter since Jackson’s exhibition. Under the guidance of Tony Sage, Irelands most famous sportsman bookmaker and patron of the sport and Billy Madden, he set sale for America. His debut was made in Philadelphia.[26]

His career advanced at a great pace. In fact, he had secured himself a contest with Steve O’Donnell in the Heavyweight championship. His last engagement before returning to America was, again, at Dublin’s Leinster Hall. The Irishman’s exhibition attracted considerable attention. In fact, the venue was described as being ‘packed from floor to ceiling.’ The Freeman’s Journal called it the biggest boxing event since Sullivan boxed Ashton. It was also claimed that on that occasion Maher … ‘if we recollect alright had a bout with the ‘’big Boston boy’ (John L. Sullivan).[27]

The pit, or standing area for spectators, was inhabited by at least twice the number it could accommodate. Spectators hoisted themselves up on a balcony. One stout man, found himself suspended in mid-air before being dragged to safety. A crowd scaled a barrier and there was a fight outside the ring. It certainly had an air of unruliness.

Maher put the gloves on with a Londoner named Hudson. The latter lasted 40 seconds before hitting the canvas. The second opponent was a no show. Instead, Maher asked – ‘would anyone stand up against him’. There were no takers. The night was finished with a four- round sparring exhibition given by Maher and his American sparring partner and trainer, Mr. Peter Lowry.[28]

The exhibition had certainly endeared him to the home crowd before travelling to America to face O’Donnell, who he defeated with some ease. The New York Herald said Maher had won the fight with three punches.[29] That he danced a few steps of a jig, and instead the referee pronounced him the winner.[30]Maher was beaten by the great Bob Fitzsimmons in 1896, but fought on for many years., staging exhibitions, for instance, in Glasgow before appearing at a boxing tournament at the Mechanics Theatre in Abbey Street Dublin where he offered a reward to any man in three kingdoms who he failed to stop in four rounds. [31]

The twentieth century: The exhibition, advantages and limitations

Modern day boxers study footage of their opponent, but they rarely get a chance to actually spar with them. However, the exhibition once afforded this. Jem Corbett (WHC 1892-1897) who defeated John L. Sullivan in 1892, later claimed that it was the four rounds of sparring (both in formal evening attire) that …’’ was a valuable insight, for no matter what you see outside the ring it is nothing to what you find out up there sparring.’’ [32]

Sullivan’s defeat was the end of an era and it shocked many and perhaps none more than his long-term sparring partner Jack Ashton.

Indeed, Ashton took it so badly that he neglected his health to such an extent that his friends became worried. Shortly after the close of Christmas holidays in 1892 he was taken sick and breathed his last breath January 6, 1893.[33]

Jim Jefferies (WHC 1899-1905) arrived in Belfast in 1899, a special train taking him to Dublin where he exhibited at the Lyric Theatre.[34] This certainly aroused public interest and the theatre increased its price because of the supposed cost of engaging the champion. On the night Jeffries and John Dunkhorse, the American heavyweight, fought four rounds, and although it wanted something of realistic earnestness, and suggested now and then a brotherly friendship, a finer display of skilful sporting could not within the time be given. [35]

The Cork crowd anticipated Jefferies at the Palace Theatre. On offer that night was two performances, the first an exhibition with Dunkhorse, and the other a demonstration of the methods in preparation to meeting Dundalk’s ‘Sailor’ Sharkey. The Evening Echo reported that the champion and Dunkhorse played with each other on the stage.

Some boxers preferred the lucrative and safer art of exhibition matches to the competitive fights.

There were ‘very short rounds’ (not totalling 56 seconds each, while Queensbury rules implied 3 minutes) which disappointed the Corkonians. Jefferies caused further disheartenment when he declined to meet brewery employee and local hero John O’ Connor. [36] This episode showed the limitations of the exhibition. On that occasion the highly scripted actions had disappointed a crowd that had paid for ‘action’ and wanted their money’s worth.

Tommy Burns (WHC 1906-08) was no fan of the exhibitions. Speaking about British champion Gunner Moir, he noted that the latter had only fought 4 men in two years. All the rest of his time, and his only chance of making a living, was by exhibition sparring. He pointed out that sparring, i.e., putting on the gloves with a man that was not in the same class, and taking care not to hurt, brings the fighter down to the level of the exhibition partner.[37]

Burns remained a very active fighter instead and he faced Wexford’s Jem Roche at Dublin’s Theatre Royal (Hawkins Street) on St Patricks Day 1908. In the audience was the heavyweight Jack Johnson who attended every one of Burns title defences and he taunted Burns at every opportunity. Calling on Burns to give him his shot. Burns dispatched the Irishman in record time.

Jack Johnson did not display Burns reservations about exhibition boxing or was making too much money to care, and he attracted a large crowd to Dublin’s Empire Theatre. The big man dressed in green Knicks for the occasion. When he came on stage he was met with a storm of applause. For five minutes he boxed a ball with marked cleverness and authority before a two rounds spar with Sargent Begley of the Royal Irish Constabulary. Next, he faced Bert Smith of the Custom House.[38] Obviously, they were no match for arguably the best heavyweight in history. They didn’t have to be.

Johnson also employed his skills as referee in a bout between Thomas McGrane and Kit Curley. At the close of the curtain a loud voice from the gallery said, ‘’You’ll knock spots of Tommy Burns’’ Johnson smiled, and the house again cheered.[39] Johnson the African American had received bad press in white America. Yet his exhibition had certainly endeared him to the Irish crowd and judging by their response a close favourite had he faced Tommy Burns. Burns would meet Johnson at Rushcutters Bay Sydney Australia in December where Johnson became the first black heavyweight champion of the world, 1908-1915.[40]

On the stage and at the flicks

The next big heavyweight to visit Ireland was Jem Corbett (WHC 1892-1897) in 1894 (two years after he had defeated John L. Sullivan). Dubliners were so happy to see the sporting gentleman that they unyoked the horse and the crowd dragged his vehicle along Brunswick Street (now Pearse Street) onto the Metropole on O’Connell Street. Corbett was delighted but declined to make a speech, maintaining that he was tired from the long trip, but reminded the crowd that his mother was a Dubliner. [41]

The champion had embraced the exhibition as a part of a wider phenomenon wherein boxers capitalised on their titles by boxing exhibitions and appearing on the vaudeville stage. They often made more money that way than by accepting challenges. [42]In this fashion the exhibition and other forms of entertainment could be judged as a danger to the actual sport.

The Irish Times noted of Jem Corbett, ‘whose physique is splendid, introduced his celebrated exhibition of bag punching. It was an accomplishment in which he excels any other athlete in the world. It must be seen to be understood.’’

Jem Corbett had not strictly come to display his boxing skills. He also aimed to reunite his father with his brother (Father James Corbett, a famous priest in the days of the Land League).[43] However, he did perform at the Queens Theatre on Great Brunswick Street in a leading role in a comedy drama which featured two young men in love with the same girl. This was part of a long tradition in which fighters transitioned into the world of entertainment, a tradition that goes back to the days of Mendoza or Deaf Burke to name but two.

The Irish Times noted as the act of the drama closed Corbett, ‘whose physique is splendid, introduced his celebrated exhibition of bag punching. It was an accomplishment in which he excels any other athlete in the world. It must be seen to be understood.’’ The fifth and concluding act the excitement reached its climax, when the stage setting introduced to the audience the Olympic club at New Orleans, this setting being an exact reproduction of the scene of the great Sullivan contest.[44] The ultimate spectacle was a hybrid of boxing, bag punching and acting.

The fistic master and ferocious fighter Kid McCoy, the middleweight champion and heavyweight contender, embarked at Dublin the next year. He called on Irish sportsman Tony Sage, bringing with him his boxing ball in which he had a world-wide reputation and in which he planned to exhibit his skills during his stay.[45]

Kid McCoy later featured in the 1922 silent film ‘World’s Champion ‘which included a boxing rendition. Yet, it was in 1894 that Jem Corbett returned to America and boxed an exhibition (specially arranged for film) with Peter Courtney, which was recorded on Thomas Eddison’s kinetoscope. This was the first motion picture of a fight[46][1] but by no means the last. A film of Dubliners favourite Peter Maher being knocked out by Bob Fitzsimmons is said to have existed. Though the first mainstream feature length film of a fight was Corbett vs. Fitzsimmons on St. Patrick’s Day 1897 and this firmly on the entertainment list. Fictionalised accounts of ring encounters were soon to follow.[47]

John L. Sullivan (though not filmed in the ring) had also adjusted his career. His theatrical Honest Hearts and Willing Hands was very popular. He also continued the age-old tradition; joining his one-time antagonist Jake Kilrain on a tour. They led at the start of the Hippodrome season at the Theatre Royal on Dublin’s Hawkins Street in 1910.[48] The Brooklyn Citizen described how the orchestra played ‘’come back to Erin’’ and that the men boxed a few rounds and told a few stories.[49] It is important to state that they were in their early fifties, both overweight and still giving boxing exhibitions.[50]

Meanwhile, Irish cinemas continued to supply fistic entertainment and notably the cinematograph pictures of the defeat of Jim Jeffries by Jack Johnson which were on show at the Rotunda Dublin in 1910. The Irish Animation Picture Company had secured the European rights while others like the London County Council had for example prohibited the controversial fight.[51] Most arguments against the fight had a strong racial element. In the United States, for example, the film was supressed by municipal and state authorities. Whereas Cardinal Gibbons of Baltimore seen it as contaminating the morals of children[52], and in Dublin Archbishop William Walsh similarly opposed the cinematograph on a point of its perceived brutality.[53] Yet, cinematic displays of boxing continued and there were also hybrid films on offer at Irish cinemas, like ‘A Pit Boy’s romance’ (1918) that, featured Jimmy Wilde (Welch flyweight) and integrated some 5-rounds of a boxing exhibition.[54]

The last round

Though boxing at the cinema has been well documented the exhibition boxing tours rarely inspired the sports historian. Therefore, it has been largely avoided as an area of historical research. Yet, it undoubtedly, has its history and one in which the patron, promotor and boxer acknowledged its universal appeal. The tours were dominated by the big-name heavyweights (who were regarded as the greatest symbol of manhood), and who utilised the skills they perfected for prize fighting to supplement their income.

This, very visible and more controlled aspect of the sport did not hurt their profile. Alternatively, it made them fashionable while it offered the general public the chance to observe and even interact with their heroes.

It was such a standard endeavour that the Irish Times felt the need to note that Gene Tunney (HWC 1926-1928) would not exhibit while in Dublin in 1928 (had hung up his gloves).[55] Had he chosen, this would have been financially rewarding for the heavyweight always filled the house (often beyond capacity) and the adjoining streets too. The gigantic Primo Carrera (WHC 1933-1944) – the only Italian boxer to have fought for the title)[56] easily attracted large crowds to an exhibition at Dalymount Park in 1932.[57] It mattered not that the hulking Italian had lost to Larry Gains in London a few days earlier.

The 2017 fight between Floyd Mayweather and Conor McGregor displayed many of the hallmarks of the exhibition

Modern boxers like the fighters before them use the exhibition, the ring and the stage in tandem. They are natural entertainers. While the lines between exhibition and competitive boxing are occasionally blurred. The 2017 fight between Floyd Mayweather and Conor McGregor displayed many of the hallmarks of the exhibition. But, apparently, was not.

The resurgence of exhibition boxing that followed has continued to attract aged champions and it continues to prove very lucrative. And yet, women’s boxing which initially had a strong exhibition element has remained strictly competitive. Though, the exhibition will continue to diversify, to accompany, and at times rival the true sport.

References

[1] William J Baker The Leisure Revolution in Victorian England: A Review of recent literature Journal of Sports History Vol. 6, No. 3 (Winter, 1979) p. 84.

[2] The case in England R v. Coney, 1882, had resulted in bare-knuckle boxing being an assault that occasioning actual bodily harm an essentially ended the era of the bareknuckle prize ring in England.

[3] The Law Journal June, 17 1882.

[4] The Irish Examiner March 01, 1888.

[5] Elliot J. Gorn The Bare-Knuckle Era -origins of the Ring quoted in The Cambridge Companion to Boxing (ed.) Gerald Early (Cambridge 2019) p. 49.

[6] Belfast Newsletter Dec, 12 1894.

[7] Elliot J. Gorn John L. Sullivan: ‘The Champion of All Champions. The Virginia Quarterly Review Vol. 62, No. 4 (Autumn 1986), pp. 620-1.

[8] The Ring Vol. XXX June 1951. No. 5.

[9] Gerald R. Gems Boxing: A Concise History of the Sweet Science (New York 2014) p. 28.

[10] Irish Examiner Dec 23 1887.

[11] ‘’ Not fewer than fifteen thousand people had gathered at the steamboat in the company of two brass bands, who played patriotic tunes like the ‘Wearing of the Green’ the party then proceeded to the Grosvenor Hotel with the crowds in toe. The did not disperse until Sullivan had called out ‘I can lick any son of a bitch in the house’

[12]The Life and Reminiscences of a 19th Century Gladiator by John L. Sullivan champion of the world

With Reports of Physical Examination and Measurements, illustrated by full-page half-tone plates, and by Anthropometrical Care By Dr Dudley A. Sargent (Boston, 1892) p. 193.

[13] Kasla Boddy Boxing A Cultural History (London, 2019) p. 110.

[14] ’Champion of Champions’’ belt never reached Ireland as Sullivan refused to pay the duty of £120 and it remained in a bonded warehouse in Liverpool.

[15] The Evening World December 14, 1887.

[16] Irish Examiner Nov 23, 1887.

[17] Christopher Klein Strong Boy: The life and times of John L. Sullivan, Americas first sporting hero P. 134.

[18] Nicole Hendricks, Mary Lou Sheffer Sullivan vs. Kilrain: Mississippi’s Legendary Boxing Match

The Southern Quarterly, Vol. 59 No. 3 (Spring 2019) PP 95-96.

[19] Maurice Golesworthy The Encyclopaedia of Boxing (London 1960) p. 188.

[20] The Sketch Jan. 31, 1884.

[21] Jake Kilrains Life and Battles also A Complete Prize Fight with Jem Smith, or $10,000, the Police Gazette Diamond Belt and Champion of the World with Illustrations by William E. Harding (New York 1888) p. 16.

[22] James J. Corbett The Roar of the Crowd the true tale of the rise and fall of a champion (New York 1925) p. 135.

[23] Bob Petersen Peter Jackson a biography of the Australian Heavyweight Champion, 1860-1901 (Sydney Australia 2005) p. 108.

[24] Belfast Newsletter Feb 10, 1891.

[25] Maurice Golesworthy The Encyclopaedia of Boxing (London 1960) p. 77.

[26] John McCormick (‘’Macon’’) The Square Circle or stories of the prize ring being Macon’s description of many pugilist battles, fought with bare knuckles or boxing gloves, with numerous anecdotes of famous fighters, to which is added how to be young at fifty, a treatise on the proper method of living of great value to all men (New York 1897) p. 249.

[27] Freemans Journal August 16, 1895.

[28] Irish Times August 24, 1895.

[29] The New York Herald Nov 13. 1895.

[30] John McCormick (‘’Macon’’) The Square Circle or stories of the prize ring being Macon’s description of many pugilist battles, fought with bare knuckles or boxing gloves, with numerous anecdote of famous fighters, to which is added how to be young at fifty, a treatise on the proper method of living of great value to all men (New York 1897) p. 253.

[31] Irish Daily Independent Tuesday 24, 1897.

[32] W. Buchanan-Taylor and James Butler What do you know about Boxing? (London 1947) p. 114.

[33] The Portrait Gallery of Pugilist America from their contemporaries from James J. Corbett to Tom Hyer with biographical sketches and authentic records of their victories and defeats embracing all the men of note of all nations connected with the pugilistic arena by Billy Edwards (Philadelphia 1894) not numbered.

[34] Evening Herald September, 12, 1899.

[35] Denis Condon Early Irish Cinema 1895-1921 National University of Ireland Maynooth (Irish academic press 2008) p. 55.

[36] The Evening Echo Sept 15, 1899.

[37] Tommy Burns Scientific Boxing and Self Defence (1908) p. xv.

[38] This may not have been the Custom House in Dublin. More likely the boxer Bert Smith of the Custom house, London.

[39] Sunday Independent August 30, 1908.

[41] Irish Daily Independent July 09, 1894.

[42] John Grasso Historical Dictionary of Boxing (Toronto 2014) P. 8.

[43] James J. Corbett The Roar of the Crowd the true tale of the rise and fall of a champion (New York 1925) p. 227.

[44] Irish Times July 10, 1894.

[45] Freemans Journal Oct, 28, 1885.

[46] John Grasso Historical Dictionary of Boxing Toronto 2014) p. 8.

[47] Bruce Babington The Sports Film: games people play (Columbia University 2014) p. 41.

[48] Irish Independent 25.02.1910

[49] The Brooklyn Citizen March 02, 1910.

[50] Colleen Aycock and Mark Scott Joe Gans a biography of the first African American world champion (London 2008) p.130.

[51] The Irish Times 22 Aug 1910.

[52] Dan Streible A History of the Boxing Film, 1894-1915 Social Control and Social Reform in the Progressive Era Film History Vol. 3, No. 3 (1989) pp. 237-240.

[53] The Irish Times 22 Aug 1910.

[54] Connacht Tribune Feb 09 1917.

[55] Irish Times Aug 24, 1928.

[56] Frederic Mullally Primo The Story of ‘Man Mountain’ Carnera -World Heavyweight Champion (London, 1991) p. 1.

[57] Irish Times June 2, 1932.