‘Ireland and the World Stand Appalled’: The Limerick Curfew Murders, 1921

By Seán William Gannon

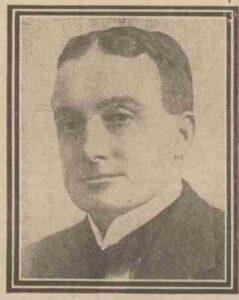

Late on a March night in 1921, as Limerick city slept under a military curfew, armed and masked men descended on three addresses in the city. By the following morning, three men at those addresses were dead, including the lord mayor of the city, George Clancy and his immediate predecessor in the job Michael O’Callaghan.

Who had carried out these ‘Curfew murders’ and why? This article will investigate.

Limerick in the War of Independence.

Limerick was at the forefront of the republican struggle during Ireland’s War of Independence in both political and military terms and its citizens paid a high price.

The provisions of the Restoration of Order in Ireland Act of August 1920 strengthened the hand of the local Crown Forces and, in December, Limerick became part of what IRA chief of staff Richard Mulcahy would call the ‘War Zone’ – a martial law area mainly comprising the six counties of Munster garrisoned by the British Army’s 6th Division.

In Limerick, the ‘dirty war’ culminated on the night of the 6/7 March 1921 when three men, including the Lord Mayor of the city, were brutally shot dead at their homes.

These developments greatly facilitated a policy of ‘unofficial’ reprisals against Irish republicans which, by the turn of 1921, had assumed the character of a dirty war. In Limerick, this dirty war culminated on the night of the 6/7 March 1921 when three men, including the Lord Mayor of the city, were brutally shot dead at their homes.

Although British officialdom attributed these killings to radical elements of the local IRA, they were in fact the work of members of the Crown Forces and were widely recognised as such at the time. The assassinations sent shockwaves through the city and country and made headlines around the world.

Victims

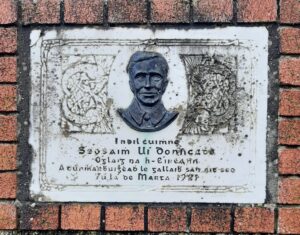

The first victim of these Curfew Murders was a 25-year-old IRA Volunteer named Joseph O’Donogue. A native of Ballinacargy, Westmeath, he had joined the Irish Volunteers in 1917 and was ultimately promoted to section leader with D Company, 1st Battalion, Athlone Brigade IRA – described by his company captain as ‘the ideal Volunteer … a very willing, sober, honest and upright worker for the cause’.[1]

O’Donoghue relocated to Limerick city in late 1919 to take up a managerial position with the British & Argentine Meat Company on William Street, where his ‘easy, courteous and affable disposition’ proved popular with colleagues and customers alike.[2] He quickly established a presence in local nationalist circles. Most significantly, he gave ‘splendid service’ to the city branch of the Gaelic League and was an active and ‘exemplary’ member of E Company, 2nd Battalion, Mid-Limerick Brigade IRA.[3]

The three victims were Joseph O’Donoghue, George Clancy and Michael O’Callaghan.

At around 11.40 on the night of 6 March 1921, a small party of disguised and armed men called to O’Donoghue’s lodgings at ‘Tigh na Fáinne’ on Janesboro Avenue as the household was readying for bed. The men demanded entry of the landlady, Bridget Liddy, and on establishing O’Donoghue’s identity, removed him from the house.

Liddy told the consequent military court of inquiry that the raiders ordered her to remain inside until morning on pain of being shot and, recently widowed and afraid for her children, she complied. She eventually came out to find O’Donoghue’s body on the side of the road near her gate. Court evidence presented by an army doctor indicated that he had been shot eight times.

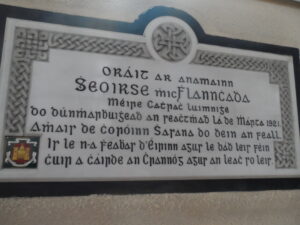

The second victim that night was the mayor of Limerick City, George Clancy. Born in Grange, county Limerick in 1881, his family had strong Fenian associations and, in the words of his Bureau of Military History biographer, he ‘drank in the tents of militant Irish Nationality with his mother’s milk’.[4] Thus, he became a ‘Gaelic Leaguer before the Gaelic League, a Sinn Féiner before Sinn Féin’, who went on to work ‘in every department of Irish National Endeavour – educational, physical, political, economic’.[5]

As a student in Dublin’s University College, for example, Clancy was the leading spirit in Cumann na bPáirtidhthe (‘The Confederates’), and he established a campus branch of the Gaelic League. Clancy continued his immersion in Irish revivalism and republican activism throughout his postgraduate career as a language teacher.

He was a key figure in the Gaelic League in Limerick City, where he taught Irish from 1908 until 1918 (when he suffered a serious bout of Spanish ‘Flu), and he was a founder member of the area branch of the Irish Volunteers in 1914. He was also a senior IRB leader and served as adjutant and vice officer commanding with the 1st Battalion, Mid Limerick Brigade IRA. Clancy eschewed parliamentary politics for most of his life.

According to his wife Mary, he had no faith in the Westminster system and rejected two invitations to join the Irish Party, one of them extended by John Redmond himself.[6] However, Sinn Féin’s entry into electoral fray in 1917 saw him take an increasingly activist stance. He campaigned for the party in both the East Clare by-election in July and the General Election of 1918, and he was a Limerick agent for the First Dáil Loan. Clancy stood as a Sinn Féin candidate in the municipal elections of January 1920 and was elected senior alderman on Limerick Corporation. He was elected mayor of Limerick city one year later.

A little after 1am on the morning of 7 March 1921, the Clancys were roused from their sleep by loud knocking and, as Crown Forces’ raids on their home were becoming routine, they went down. Mary opened the door to find herself confronted by three armed men in overcoats, goggles, and hats. Quickly sensing real danger, she attempted to deny the men entry, but they forced their way past her and shot her husband dead in the hall. Mary was herself shot in the hand as she tried to defend him.

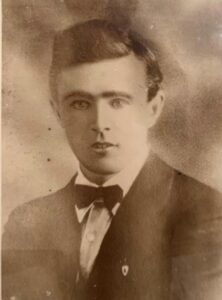

Clancy’s immediate predecessor as Limerick City mayor, Michael O’Callaghan, was the third victim of the Curfew Murders. He was born in Eden Terrace, Limerick city in 1879, the son of Edward and Ellen O’Callaghan who owned the successful City Tannery. Although ill-health prevented him receiving formal childhood education, he was a natural scholar and went on to qualify as an industrial chemist in London. This equipped him to take over the running of the family business, ultimately as managing director.

O’Callaghan came from what his wife, Kate, called ‘sound national stock on both sides’.[7] He maintained an active interest in Irish revivalist culture through membership of the Gaelic League and he strongly advocated for the strengthening of Ireland’s native economy through his work with Irish industrial associations. O’Callaghan also participated in local nationalist politics.

He joined Limerick’s original Sinn Féin club in 1905 and was a member of its O’Rahilly Club when he died. However, he was also active in the Home Rule movement through his involvement with All for Ireland League and as a founder member of the Limerick branch of the Irish Nation League in Limerick in 1916. O’Callaghan was a prime mover in the foundation of the Limerick Irish Volunteers and he sat on its executive committee until 1916.

Following the Easter Rising, he served as treasurer of the Limerick branch of the National Aid Association and Volunteers’ Dependants Fund and he agitated for republican prisoner release.

Like Clancy, he campaigned for Sinn Féin in the 1917 East Clare by-election and in the General Election of December 1918, when they together wrote Michael Colivet’s election address. O’Callaghan’s own career as a public representative commenced with his election to Limerick Corporation in 1911 and culminated in his inauguration as Sinn Féin mayor of Limerick city in January 1920. By then, politics was his particular focus (according to Kate, he was by now ‘the brains of Sinn Féin in Limerick’) and he did not hold IRA rank during the War of Independence.[8]

Shortly after 1am on the morning of 7 March 1921, two men disguised with goggles and hats called to the O’Callaghan residence, St Margaret’s on the North Strand, and demanded that Michael come to the door. Assured that they were Crown officers, and as accustomed to raids as the Clancys, he and Kate went down. When Kate opened the door the men opened fire at close quarters and, despite her strenuous attempt to protect him, Michael was mortally wounded.

Perpetrators

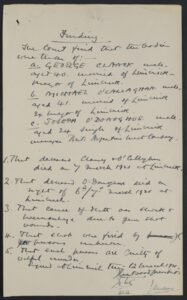

The Limerick Curfew Murders made front-page news internationally as ‘Ireland and the world [stood] appalled’ at their wanton brutality.[9] A military court of inquiry was immediately convened, but adjourned until after the funerals. Hearings commenced on 11 March and fifteen witnesses gave evidence. All but five were members of the Crown Forces. Kate O’Callaghan and Mary Clancy refused to attend, arguing that military courts were ‘but a farce and a travesty of justice’.[10]

And, indeed, to their minds, the Curfew Murders inquiry bore this out; they believed that the court’s eventual finding that that O’Donoghue, O’Callaghan, and Clancy had been wilfully murdered ‘by persons unknown’ was a deliberate obfuscation of the fact that they had been killed by Crown Forces.

The court’s questioning of key witnesses was, at the very least, culpably incompetent. But firm evidence has yet to emerge that it consciously engaged in a cover-up. Limerick’s military commander, Colonel Commandant Archibald Cameron, alone addressed the issue of the perpetrators’ identities in his evidence and he strongly argued for ‘the extreme improbability of the Crown Forces being connected with the crimes’. For while O’Callaghan and Clancy were certainly ‘advanced Sinn Féin politicians and connected with the Republican Army … they were opposed to violence and did their best to prevent outrages’.

The British court of Inquiry maintained that the three had been assassinated by radical elements of the IRA for their alleged moderation.

It therefore seemed to Cameron ‘incredible that people should believe that, for no apparent reason, Forces of the Crown should select two victims who were generally supposed to be amongst the influential party of citizens who had striven to keep the peace’.[11] The mayoral Catholic chaplain, Fr Philip O.F.M., provided unwitting support for this theory by describing O’Callaghan and Clancy in similar terms: O’Callaghan was ‘most moderate in his views and a peace-loving man’ and ‘a restraining influence’ on militant republicans, and Clancy ‘was of the same thinking’.[12]

Far more credible to Cameron was the theory that O’Callaghan and Clancy had been killed by the militants that they tried to restrain. He reported to his superiors that he had ‘little doubt … that the murders were committed by the extreme republicans because Clancy and O’Callaghan resisted suggestions for outrages on the Crown Forces’.[13]

Cameron adduced as evidence documents seized during a raid on IRA GHQ in Dublin which laid bare frustration on the part of the East Limerick Brigade at perceived inactivity in the county’s two other brigades, particularly Mid Limerick where ‘possibly 400 rifles were lying idle’. By eliminating O’Callaghan and Clancy, republican radicals hoped to, not only remove their restrictive influence on IRA activity in Limerick city, but ‘provoke attacks on the Crown Forces’ who would, inevitably, be blamed for their deaths.[14]

Cameron, described by historian Tom Toomey as ‘an honourable man … [who] seems to have deluded himself into thinking the [murders] were carried out by the IRA’,[15] reported his findings to his superiors, including Ireland’s general officer commanding, General Sir Nevil Macready who, on the evidence of his memoirs, believed them in turn.[16] Although this explanation took no account of O’Donoghue’s murder, it became established as the Crown line.

The suggestion that ‘extreme republicans’ were responsible for the Curfew Murders was roundly rejected by nationalists in Limerick, for whom the culpability of Crown Forces was never in doubt. Kate O’Callaghan was especially contemptuous. Certain that ‘this story of a Sinn Féin murder gang was planned when the murders were being planned’, she embarked on a campaign to bring the truth out through an independent public inquiry.[17] When this was rejected by British prime minister David Lloyd George, she published and circulated a pamphlet called The Limerick Curfew Murders.[18]

Therein O’Callaghan charged that the murders had been the work of a five-strong police death squad operating out of Cruise’s Hotel which was providing a city base for RIC Auxiliary Division (ADRIC) ‘G’ and ‘H’ company cadets at the time. In the scenario that the pamphlet presented, all five were involved in the murder of Joseph O’Donoghue, following which three proceeded to kill George Clancy, and two her husband.

Kate O’Callaghan, widow of Michael, stated that the murders were the work of a five-strong police death squad operating out of Cruise’s Hotel which was providing a city base for RIC Auxiliary Division

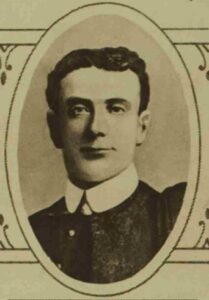

Although she did not refer to him by name, O’Callaghan clearly identified one of the latter’s assassins: George Nathan, a section leader and intelligence officer with ADRIC ‘G Company’ based in Killaloe. Her main evidence for this was his accent. O’Callaghan stated that she had known of Nathan since 27 January when his presence at a dance she attended caused her to enquire as to his name, a name it transpired was already familiar to her as that of an ADRIC officer of bad reputation.

Three-and-a-half weeks later, this same man led a raid by ‘English police’ on her house. Afterwards, both she and her husband noted his ‘charming and cultivated voice’ and speculated on whether he was English himself: ‘we could come to no conclusion about his nationality as his name suggested that he might be of Jewish extraction’.[19]

Interviewed by the Bureau of Military History over thirty years later, Mary Clancy stated that she and her husband had too noted Nathan’s ‘charming, cultivated voice’ during a raid on their house and Nathan confirmed his presence at both raids in his evidence to the court of inquiry into the murders.[20] That Nathan’s voice was as the Clancys and O’Callaghans described was confirmed by an army colleague in Spain many years later who said his ‘accent was too gentlemanly to be real’.[21]

Thus, although he was disguised with a hat and goggles on the night of her husband’s murder, O’Callaghan immediately recognised Nathan by his voice and subsequently declared herself ‘prepared to swear that [he] guided the murderers to our house, and helped to murder my husband’.[22]

In 1961 the military historian Richard Bennett confirmed O’Callaghan’s claim. Following the publication of his book The Black and Tans two years earlier in which he had repeated the Crown line on the Curfew Murders, he was contacted by a former member of ADRIC ‘G Company’ who revealed the real prime movers to have been section leader and intelligence officer, George Nathan, and another ‘G Company’ cadet.[23]

George Nathan, an Auxiliary Intelligence officer, who later died in the Spanish Civil War fighting in the International Brigades, was widely thought to have planned the killings.

As Nathan was dead by this time; a rather colourful character, he had been killed in July 1937 while fighting with the International Brigades in the Spanish Civil War, Bennett tracked his accomplice to London. Although he declined to name him in the article he published on their interview, it provides sufficient personal particulars to identify him as William N. Harrison from Dublin.

By then a 75-year-old ‘wreck of a fine Irishman’ living in a Bayswater bedsit, Harrison admitted accessorial guilt; he and Nathan had ‘knocked off a couple of Shinners’ that night, although he denied shooting any himself, having ‘no stomach for that kind of job’.[24] (This was a falsehood: in actuality, Harrison fired the shots that killed Michael O’Callaghan).[25] Then, in the 1980s, a former member of the International Brigades claimed that Nathan had been secretly ‘tried’ for the murders by a group of Irish Republican comrades in Spain and admitted his guilt.[26]

Parties

Kate O’Callaghan was convinced that Nathan’s death squad could have operated only with the connivance of the local Crown Forces, as the city was entirely under their control during curfew. She saw as particularly sinister the fact that soldiers at the Strand Barracks had declined to apprehend George Clancy’s assassins despite hearing them passing by the building in both directions, as well as the fatal shots.

Although the curfew was not rigorously enforced in Limerick city, troops were under direct orders to investigate shootings and this was clearly not done in Clancy’s case. Whether this signified collusion, rather than a ‘lack of energy and initiative’ as Cameron assumed, is unproved.[27]

O’Callaghan further claimed that members of the city’s regular RIC were complicit. District Inspector Leslie Ibbotson at William Street station formed her particular focus in this regard: ‘I accuse him of being a party to the murder[s]’, she declared in The Limerick Curfew Murders, and she cited an accumulation of circumstantial evidence she said proved that he had foreknowledge of the killings and facilitated their perpetrators’ escape.[28] For example, in conversation with Fr Philip on their way to St Margaret’s, Ibbotson had spoken of plural ‘murders’ when only that of her husband was publicly known, and he had confidently attributed them to a ‘Sinn Féin murder gang’ before he arrived to investigate the scene.

Most significantly, she accused him of delaying his departure from William Street station for up to 35 minutes to allow the assassins to make their way unapprehended back to Cruise’s Hotel. In a close examination of the evidence, Tom Toomey concurs, noting that Ibbotson was himself a former Auxiliary and had spent the evening of 6 March socialising at the hotel: his ‘highly suspect’ behaviour (particularly his ‘reluctance … to emerge from [William Street] barracks before he felt the coast was clear’) casts him as ‘an accessory’ to the murders.[29]

Ibbotson explicitly denied any involvement. In July 1933, he submitted to a writing school in Connecticut twelve sample chapters of a proposed memoir of his RIC service, Recollections of the Irish Rebellion, one of which dealt with the Curfew Murders; it maintained the Crown line that ‘radicalist IRA gunmen’ carried out ‘these callous crimes’.[30]

However, it is a transparent exercise in self-exculpation. While it does not reference O’Callaghan’s pamphlet, Recollections presents as a point-by-point rebuttal of her charges against him therein. Yet its explanations for his actions that night are, at best laboured, at worst unconvincing, its narrative replete with misrepresentations and half-truths clearly intended to deflect personal blame.[31]

Kate O’Callaghan maintained that the murders were part of sanctioned policy of ‘terror’ by the Royal Irish Constabulary.

Recurrent claims of wider RIC complicitly in the Curfew Murders remain unproved and appear rather unlikely. Suspicion has centred on Sergeants James Horan and William Leech, both of notorious repute in revolutionary Limerick.[32] However, no evidence of involvement in the Curfew Murders has yet emerged and, as Toomey has noted, ‘it was unlikely that Nathan would involve a regular RIC sergeant in his activities’ as their movements were recorded in the station diary.[33]

That for William Street (where Horan and Leech were based) was examined by District Inspector John Greally for the court of inquiry, and he reported that no movements were therein recorded between the return of the last RIC patrol at midnight and departure of Ibbotson’s police party (which in fact included both Horan and Greally) at around 1.45am. That Greally had himself no prior knowledge of the murders was confirmed at the court. On hearing the evidence of the medical doctor called to attend to the dying Michael O’Callaghan about meeting five men on his way, he started and ‘whispered excitedly’ in Fr Philip’s hearing that ‘it’s the Cruise’s Hotel crowd that did it’.[34]

Kate O’Callaghan maintained from the start that ‘blacker criminals [than Nathan] planned these assassinations and [that] they sit in high places’ and the overwhelming likelihood is that the murders were centrally conceived.[35]

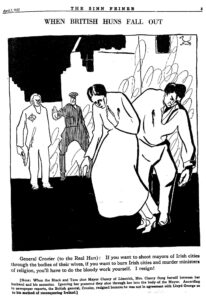

Ten years afterwards, the ADRIC’s first commandant, Frank Crozier (who was aware within weeks of the Curfew Murders that a ‘G Company’ intelligence officer was centrally involved) asserted that the men were ‘murdered by the police acting under orders as part of a plan to “do away with” Sinn Féin leaders and put the blame on Sinn Féin’ and covert squads comprising Auxiliary Division and regular RIC personnel were certainly operating in Limerick at the time.[36]

Research by John O’Callaghan indicates that the extrajudicial killings with which these squads ‘terrorized republican communities’ in the city and county were probably ‘unofficial political policy’. Cover names such as the ‘Anti-Sinn Fein Society’ and the ‘Anti-Murder Gang’ commonly sought to obscure their true status as Crown Forces.

He notes that Divisional Commissioner Prescott-Decie, who was based in William Street station, ‘certainly took a cavalier attitude to the use of force [in his area] that had been approved further up the chain of command’.[37] Indeed, George Nathan’s defence at his informal ‘court martial’ by his Irish Republican comrades in Spain was that he had been a mere foot soldier ‘detailed to do the job’.[38] That this defence was accepted by his Irish accusers suggests that he made a convincing case, and it is known that he travelled from Dublin to Killaloe on the day of the murders.

The reasons for which Michael O’Callaghan and George Clancy were targeted seem clear. They were the two most prominent ‘Sinn Féiners’ in Limerick, and both were subjected sustained intimidatory campaigns, primarily death threats and raids on their houses, in the months prior to being killed.

As Limerick city’s first Sinn Féin mayor, O’Callaghan had pledged the Corporation’s allegiance to the First Dáil and he was a constant critic of the behaviour of the Crown Forces throughout his term. He was also a key figure in the republican propaganda war in Limerick, particularly through his briefing of visiting dignitaries and foreign correspondents.

And although he was not himself an IRA Volunteer, he was, in his wife’s words, ‘a friend of the extremists’ who ‘well realised the need for a military … side to the national movement’. Consequently, ‘his logical end was murder by the hand of a hired English assassin’.[39] Clancy had dedicated himself entirely to the Irish Republic on his own election as mayor, declaring that he ‘would be 100 per cent wool and unshrinkable’ in its pursuit.[40]

He was also an IRA officer and, although the extent to which he participated in insurgent operations is unclear, he was believed by the Crown Forces to be actively involved. What is clear is that he had great status and influence within Limerick’s republican ranks and was a role model to many therein. In the words of his wife Mary, ‘dimly his murderers knew those things and that was why he died’.[41]

The reasons for which O’Donoghue was targeted are less certain, for he was not a prominent IRA member. It is believed that he was suspected by British intelligence of using his managerial role at the British & Argentine Meat Company to smuggle arms into Ireland, and there is anecdotal evidence that ‘unidentified men had been checking mail for his [Limerick] address’ in his native Westmeath in the weeks prior to his death.[42]

‘How women suffered’

Writing in support of a compensation claim for the death of Joseph O’Donoghue lodged by his father under the terms of the Army Pensions Act, 1932, Kate O’Callaghan stated that the Curfew Murders ‘did much to bring the Black-and-Tan terror to an end’ and there was certainly some truth in this.[43]

Writing in support of a compensation claim for the death of Joseph O’Donoghue lodged by his father under the terms of the Army Pensions Act, 1932, Kate O’Callaghan stated that the Curfew Murders ‘did much to bring the Black-and-Tan terror to an end’ and there was certainly some truth in this.[43]

Such atrocities, perpetrated by Crown Forces acting ‘more like terrorists than policemen’, and covered-up by corrupt military courts of inquiry, helped lose Britain the propaganda war that became critical to success the success of its counterinsurgency.[44] Central to the propaganda victory were widows such as Kate O’Callaghan and Mary Clancy, both active republicans in their own right, primarily through their involvement with the Gaelic League and Cumann na mBan.[45] Their wartime experiences, as Courtney McKeon has observed, were self and otherwise presented ‘in terms of their suffering for propaganda value so as to increase sympathy for the “Irish cause”’.[46]

Our knowledge of the Curfew Murders is mediated mainly through female voices, which turns a spotlight on female trauma during the Irish Revolution and after

That our knowledge of the Curfew Murders is mediated mainly through their voices turns a spotlight on female trauma during the Irish Revolution and after. The powerful testimonies of O’Callaghan, Clancy, and Joseph O’Donoghue’s landlady, Bridget Liddy, foreground a psychological suffering which, as Linda Connolly has noted, ‘was more typically contained in the private world of Irish women’s lives rather than recorded in official archives or made public’.[47]

Their accounts of military and police raids on their homes impart a deep sense of the anger, fear, and humiliation felt by Irish women at such violent invasions of their domestic and personal space. That of Mary Clancy in particular, tellingly entitled ‘How Women Suffered’, conveys the atmosphere of sexual menace that often permeated such raids.[48]

The deeper societal legacies of the Curfews Murders (like all revolutionary crimes of its kind) are difficult to assess, the testimonies of the victims’ descendants sometimes suggesting a transgenerational trauma still little understood and the cumulative impact on which on Irish society is only now being adequately explored. Certainly, the murders remain the central event in the social memory of the War of Independence in Limerick city, where O’Donoghue, O’Callaghan, and Clancy are memorialised in several places and their names are long inscribed on the streets.

References

[1] Military Archives (MA), Military Service Pensions Collection (MSPC), DP2623 Joseph O’Donoghue: Murray to Military Service Registration Board, 5 September 1933.

[2] ‘Honouring a Volunteer’s memory’, Limerick Leader, 11 March 1950.

[3] Ibid.; MA, MSPC, DP2623, Hartney to Military Service Registration Board, undated.

[4] MA, Bureau of Military History Witness Statements (BMH WS) 806, Mary, Bean Mhic Fhlannchadha, undated, p. 2.

[5] Ibid., p. 1.

[6] Ibid., p. 4.

[7] MA, BMH WS 688, Kate O’Callaghan, 14 June 1952, Annex: ‘Michael O’Callaghan, Mayor of Limerick 1920’, p. 1

[8] Ibid., p. 3.

[9] West Australia Record, 16 April 1921.

[10] Freeman’s Journal, 12 March 1921.

[11] Quotations from Cameron’s evidence to the military court of inquiry. British National Archives (TNA), War Office files (WO) 35/147A/62: ‘Courts of Inquiry in lieu of inquests: George Clancy. Michael O’Callaghan, Joseph O’Donoghue’, fos 58-64.

[12] TNA, WO 35/147A/62, fo. 27.

[13] TNA, WO 35/147A/62, Cameron to Strickland, 13 March 1921.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Thomas Toomey, The War of Independence in Limerick, 1912-1921: also covering actions in the border areas of Tipperary, Cork, Kerry and Clare (Limerick, 2010), pp 547, 550.

[16] ‘Judging from the methods of the rebels, not only at the time but at a later period, when the Free State Government was in power, the supposition that these two men were murdered by their compatriots as a warning to others who might be inclined to dissent from the policy of the extremists is by no means extravagant’. Sir Nevil Macready, Annals of an active life, vol. 2 (London, 1925), p. 546.

[17] MA, BMH WS 688, p. 30.

[18] Kate O’Callaghan, The Limerick Curfew Murders of March 7th, 1921: The case of Michael O’Callaghan (councillor and ex-mayor) presented by his widow (Chicago, 1921). It also forms the great part of Kate O’Callaghan’s BMH witness statement, pp 1-47.

[19] Ibid., pp 11-16. Nathan did have Jewish heritage: while baptised into and raised (at least nominally) in his mother’s Anglican faith, his father was Jewish and Nathan himself self-identified as Jewish in later life.

[20] A textual analysis of the relevant passage suggests that Clancy used The Limerick Curfew Murders as an aide mémoire to her interview. MA, BMH WS 806, p. 13; TNA, WO 35/147A/62 fo. 56.

[21] Thomas Wintringham, English captain (London, 1939), p. 132.

[22] As the Irish Bulletin noted, Kate O’Callaghan and Mary Clancy’s description of the goggles that the murderers wore ‘tallied with that of the “goggles for night practice” officially supplied to the British Military and Constabulary posts in Ireland’. O’Callaghan, Limerick Curfew Murders, p. 26; Irish Bulletin, 4/45, 9 March 1921.

[23] Richard Bennett, The Black and Tans (London, 1959).

[24] Richard Bennett, ‘Was this the Limerick assassin of ’21?’, Irish Press, 29 March 1961. This article was originally published ‘Portrait of a killer’ in the Spectator, 24 March 1961.

[25] MA, BMH WS 688, p. 21

[26] Imperial War Museum London (IWM), Sound Archive 9722, Maurice Levine interview (Reel 2), undated (https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80009507). See also Maurice Levine, From Cheetham to Cordoba: a Manchester man of the Thirties (Manchester, 1984), p. 39.

[27] TNA, WO 35/147A/62, Cameron to Strickland, 13 March 1921.

[28] O’Callaghan, Limerick Curfew Murders, p. 24.

[29] Toomey, War of Independence in Limerick, pp 547-52.

[30] L. H. P Ibbotson, Recollections of the Irish Rebellion (MS in possession of Bruce Ibbotson, Australia, undated c. 1932/3). I am grateful to Mr Ibbotson for providing me with this manuscript.

[31] For the text and an analysis of Ibbotson’s chapter on see Seán Gannon, ‘“I accuse …”: District Inspector L.H.P. Ibbotson and the Limerick Curfew Murders’, Old Limerick Journal 55 (2020), pp 28-34.

[32] Leech was shot dead in Dublin in May 1922 in what was almost certainly an IRA revenge killing for his wartime misdeeds while Horan, deemed by his RIC superiors as being in ‘special danger’ from similar retribution, fled to England where he lived out the rest of his life. Ibbotson went directly to Palestine on his disbandment as an officer with the British Section of the Palestine Gendarmerie.

[33] Toomey, War of Independence in Limerick, p. 552.

[34] MA, BMH WS 688, p. 33. Two attempts to force entry to Fr Philip’s room at Limerick’s Franciscan friary were subsequently made by persons unknown. But that both occurred during curfew leaves no doubt that they were members of the Crown Forces. So fearful for Fr Philip’s safety did his superiors become that they transferred him to Dublin in May 1921. Walter Crowley’, ‘The Life and Times of Fr Philip Murphy o.f.m., 1890-1964’ (Unpublished manuscript, 1995).

[35] MA, BMH WS 688, p. 36.

[36] Freeman’s Journal, 24 May 1921; F. P. Crozier, Ireland for ever (London, 1932), pp 288-92. In an appendix to this memoir, Crozier described O’Callaghan’s The Limerick Curfew Murders as ‘a remarkable document’, the conclusions of which regarding responsibility for the murders his own contemporary investigations concurred. The fact that Crozier’s memoir was published in 1932 raises the possibility that it prompted Ibbotson either to write Recollections, or substantially address the Curfew Murders therein.

[37] John O’Callaghan, Limerick: The Irish Revolution, 1912-23 (Dublin, 2018), p. 84. Limerick Corporation refused to accept Prescott-Decie’s condolences on the deaths of ‘O’Callaghan and Clancy, as did it those extend by Cameron.

[38] IWM, Maurice Levine interview.

[39] MA, BMH WS 688, pp 1-2.

[40] MA, BMH WS 806, p. 9.

[41] Ibid., p. 20.

[42] Toomey, War of Independence in Limerick, pp 538, 543.

[43] MA, MSPC, DP2623, O’Callaghan to Military Service Registration Board, 1 September 1933.

[44] D. M. Leeson, The Black and Tans: British police and auxiliaries in the Irish War of Independence (Oxford, 2011), p. 97.

[45] According to her brother-in-law Egan, Clancy (the daughter of an RIC constable) was actually ‘a more active Irish nationalist than George, if that were possible’. New York Times, 8 March 1921.

[46] https://www.ul.ie/ULH/node/2231

[47] Linda Connolly, ‘Towards a further understanding of the violence experienced by women in the Irish Revolution’, Maynooth University Social Sciences Institute, Working Paper Series, no.7, p. 4. See also Linda Connolly (ed.), Women and the Irish Revolution (Dublin, 2020), pp 103-28.

[48] MA, BMH WS 806, pp 11-12,