The Cork Landings – August 8-10, 1922

On August 8 1922, pro-Treaty forces landed by sea in Cork, seizing the Free State’s second city from anti-Treaty forces. By John Dorney

At Passage West, a ferry port and fishing village on the estuary of the river Lee, early on the morning on August 8 1922, a steam ship the Arvonia nestled into the harbour. The anti-Treaty IRA garrison in Cobh, just across the bay, nervously followed her progress and fired warning shots with their three machine guns. There was no reply.

A sentry, member of the IRA garrison at Passage West, fired a shot across the Arvonia’s bows as she docked, but finding no response, approached the vessel along the pier, holding a lamp.

He apologised for the gunfire, but as he did so, peered into the deck of the ship. What he saw startled him. He dropped the lamp and hurridly ran back into town. Huddled together on deck were over 200 National Army or pro-Treaty soldiers, the vanguard of the Provisional Government’s seaborne assault on republican-held Cork. They clambered ashore and soon secured the town. Unloaded there were 450 troops, an 18-pounder field gun and several armoured cars. [1]

Near simultaneous landings were made at Youghal in east Cork and Union Hall, near Skibbereen in West, disgorging another 350 pro-Treaty troops.

It was the beginning of what was intended as the decisive stroke of the Irish Civil War, Michael Collins’ plan to seize back the southern capital and to bring the Civil War to a rapid end.

Political background: the Treaty split in Cork

Nowhere demonstrated the tortuous nature of the Treaty split so much as Cork city and county. It be summarised essentially thus: the majority of guerrilla fighters, from the Cork Brigades, the most active IRA units in the country, were against the Anglo-Irish Treaty, but the majority of the civilian population there favoured its acceptance. At the same time, there were very strong neutral tendencies and calls for peace among both the civil and military communities in Cork.

From almost the date the Treaty was signed, the military side of the movement in Cork was a problem for the pro-Treaty leadership. Cork-based members of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, the secret society of which Michael Collins was the President, refused to circulate the orders of the IRB’s Supreme Council to accept the Treaty as a tactical step towards ‘our ultimate aim’ (i.e. an independent Irish Republic).[2]

While the majority of the 10,000 plus IRA members in County Cork were against the Treaty, the majority of the civilian population was in favour of it.

Early in the Dail debates over the Treaty in late 1921, there were rumours that disaffected Cork republicans were threatening to shoot pro-Treaty deputies from that county. Michael Collins raised the question in private session with Minister for Defence Cathal Brugha who replied testily that he: ‘cannot deal in rumours’ and said that deputies should ‘keep their mouth shut’ and not repeat them.[3]

Once the IRA formally split over the Treaty in March 1922, the Cork Brigades overwhelmingly took the anti-Treaty side. A report from just before the outbreak of Civil War in early June 1922, from a Captain Dennehy to Collins stated there were there were only 500 Cork IRA men ‘loyal to GHQ’ currently located in Dublin and the Curragh camp. Another report from after the outbreak of hostilities in June was even more pessimistic. One M. O’Connell, told the pro-Treaty leadership that, ‘All the fighting men are with the Executive [anti-Treaty] forces’ and estimated that there were only 250 pro-Treaty fighters in Cork.[4]

Among them were only a few senior pre-Truce officers, the most prominent among them being Sean Hales, who was also elected as a .T.D. to the Third Dail in June 1922. At the outbreak of the Civil War, the only post they occupied in County Cork was in Skibbereen, which was quickly taken by the anti-Treatyites after a brief fight on July 3.

By contrast, the nominals rolls of the IRA show that over 10,000 men appeared on the membership records of the anti-Treaty IRA in the five Cork Brigades on July 1, 1922.[5] Only a fraction of these were experienced fighters and many did not have access to a weapon at all. Despite a raid on a British naval ship, the Upnor, in April 1922 which had netted the IRA over 400 rifles and 40 machine guns, the anti-Treaty IRA in Cork possessed at most 1,000 rifles at the start of the Civil War.[6] If the remainder had a weapon at all, then it was likely only a civilian shotgun. Nevertheless, this was an ominous challenge for the Provisional Government.

However, the Cork Brigades, also contained some strong neutral tendencies. Divisional head Liam Deasy and famed guerrilla leaders such as Tom Barry and Sean Moylan were among the anti-Treaty commanders, but the War of Independence commander of the largest unit, Cork No. 1. Brigade, Sean O’Hegarty along with his Intelligence chief Florence O’Donoghue, though opposed to the Treaty, refused to take part in the Civil War. The latter two later formed their own organisation, the ‘Neutral IRA’, with the aim of trying to mediate to negotiate an end to the conflict.[7]

It is also notable that the two largest and most active Cork Brigades; No. 1 in Cork city and environs and No.3 in West Cork, shed almost half their membership between the Truce with the British on July 11 1921 and the onset of Civil War in July 1922.[8]

Clearly many, whether opposed to the Treaty or not, did not have the stomach for Civil War.

But, even if tempered by some ‘neutrals’, the preponderance of anti-Treaty sentiment in the IRA did not at all reflect civilian opinion in County Cork.

In the General Election of June 1922, in the three Cork constituencies, only four seats out of fifteen were taken by anti-Treaty Sinn Fein candidates, with five going to pro-Treaty Sinn Fein, three to Labour, one to the Farmers’ Party and one to an Independent.

Counting the ‘soft’ pro-Treaty parties of Labour, Farmers and Independents, this was a pro-Treaty majority of nearly three to one. Moreover, Michael Collins, running for pro-Treaty Sinn Fein in his native county, received more than twice as many votes (over 17,000) as any other candidate.[9]

In Cork city, Labour topped the poll, with nearly 7,000 votes for trade unionist Robert Day, though 10,000 were shared between pro-Treaty Sinn Feiners Liam de Roiste and J.J. Walsh compared to just 4,000 for anti-Treaty republican Mary MacSwiney.[10]

However, again, a pro-Treaty vote was, perhaps, above all else a vote for peace rather than for further war. Many in Cork were appalled when Civil War broke out in Dublin and there were numerous peace initiatives from Cork civil bodies in July 1922.

The People’s Rights Association – a group mainly formed from the Cork business community, wrote to both sides asking for a ceasefire and for the Third Dail, elected in June 1922, but suspended since the outbreak of hostilities, to meet.

IRA Chief of Staff Liam Lynch was somewhat receptive to their calls for a ceasefire ‘if attacks on us cease’, but Collins and Arthur Griffith, heads of the Provisional Government, were not. Collins wrote back that ‘the Irregulars’ must hand in their arms; ‘the choice now is between the return of the British and the Irregulars sending in their arms to the People’s government’. Griffith concurred, stating that ‘the present military action … is necessary to enforce obedience to parliament’.[11]

This was not the end of peace initiatives however. Pro-Treaty T.D. Liam de Roiste, also called for a ceasefire as did a Women’s peace meeting at Cork Court house and the Transport Union (ITGWU) considered calling a general strike for peace – in protest at the disruption of trade at the Port of Cork, but all to no avail.[12]

The Provisional Government had embarked on the Civil War with bombardment of the Four Courts and there was no turning back until they had imposed what they considered lawful authority over the country.

Anti-Treaty occupation of Cork city

With the onset of Civil War, Cork city had come under the military occupation of the anti-Treaty IRA, who had already occupied the barracks vacated in April 1922 by the British Army and the RIC (the soon-to-be disbanded police force). They also now attempted to run a civil administration.

The mayor, anti-Treatyite Donal Og O’Callaghan attempted to keep order via the Irish Republican Police and a ‘Civil Administration Department’ of Cork No. 1 Brigade was also set up.

The Cork Examiner newspaper became an anti-Treaty mouthpiece for some time, mainly due to censorship, run by republican publicity officers Frank Gallagher and Erskine Childers.

Funding war-fighting, particularly paying and feeding fulltime soldiers – as the anti-Treaty IRA now aspired to be – is a costly affair. Unsurprisingly therefore, the republican administration in Cork city soon also began to impose taxation to fund their war effort. They successfully seized the revenue of the Customs & Excise department in Cork’s Custom House, taking in over £100,000, the equivalent of perhaps £6 million (or 7 million euro) today, in July 1922. Had this continued it would have been the major source of funds for the anti-Treaty war effort.

The anti-Treatyites ran Cork city in July 1922, with a kind of military regime, but faced an unsupprtive populace who resisted paying them taxes.

However their unpopularity, especially among the business community, meant that several attempts to levy an income tax failed. One official hid the tax forms in flour bags while a boycott of tax payments was successfully organised by Maurice Hayes, a former member of parliament the All for Ireland League and by Michael Collins’ sister, Mary Collins Powell. The Chamber of Commerce also advised their members against paying tax to anyone but the Provisional Government.[13] While there was some ‘commandeering’ of supplies, O’Donnell, a pro-Treaty activist, wrote to Michael Collins that the IRA were ‘paying for everything so that people do not turn against them.’[14]

Despite being essentially a military regime ruling an unsupportive populace, the anti-Treaty regime in Cork did not engage in systematic repression of its political enemies.

The aforementioned Maurice Hayes, was arrested and deported to England for encouraging a boycott of taxes and two pro-Treaty elections agents Joe McCarthy and Michael Mehigan, who were clandestinely recruiting for the Free State’s army, were arrested and imprisoned in the city.

However, Mary Collins Powell, who was doing likewise – indeed she and others identified nearly 1,000 potential recruits for Provisional Government forces, including 250 ex-IRA and 700 ex British Army veterans – was left alone. Unhindered too was pro-Treaty TD Liam de Roiste.[15]

Nor did the anti-Treatyites feel able to coerce Fords’ tractor factory in the city into supplying them with vehicles, which the latter refused to do, threatening to close the factory if forced to do so.

The Catholic Bishop of Cork, Daniel Coholan, had always been opposed to militant republicanism. Indeed he had denied IRA fighters sacraments in December 1920, blaming them for the British forces’ burning of Cork city. Unsurprisingly he also kept a haughty distance from the anti-Treaty administration of Cork in 1922.[16]

Many in Cork, including many of its most wealthy and influential citizens were therefore waiting in expectation of the Provisional Government seizing the city and ‘restoring order’.

Preparations for the assault on Cork

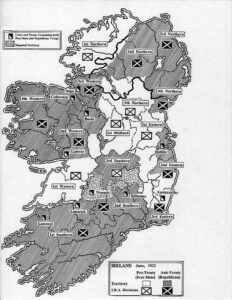

July of 1922 saw a successful pro-treaty offensive, in which the towns of Drogheda, Limerick and Waterford among others were seized by the National Army, with some sharp fighting but relatively low casualties. The anti-Treaty IRA were left with their stronghold of south Munster, defended, in theory at least, by a fighting line that ran from the south Limerick countryside to the outskirts of Waterford.

On July 26th, Collins was able to write to his colleagues, ‘we may congratulate ourselves that everything has turned out so well… we have taught the rebels lessons… which appeals to reason or patriotism failed to teach them’. It remained to dislodge the ‘Irregulars’ in their stronghold of Cork and Kerry and Collins hoped to do so by a swift knock down blow that would ‘save the good fighting men of Cork from barrenness of their leaders’ who ‘have shown themselves to be without an objective’. [17]

Collins in other words, thought that the attitudes of rank and file anti-Treatyites could be turned around once their misguided leadership was defeated. To this end, he and Emmet Dalton planned two seaborne expeditions to Cork and Kerry in the first week of August 1922, landing on the southern coast outflanking the ongoing fighting line in counties Limerick and Tipperary.

Cork anti-Treaty IRA units fought at fronts in Limerick, Waterford and elsewhere in July 1922, with the result that many of their best men were not in Cork to resist the landings.

Some Cork anti-Treatyites, such as Florence Begley later asserted that ‘we had no heart in the Civil War’ and thought that it should have ended after the fighting in Dublin. [18]

Perhaps this was so, but Cork IRA anti-Treatyites fought enthusiastically on other fronts in July 1922 outside of their home county. Sean Moylan had led an abortive expedition to County Wexford and Mick Murphy had led another, around 100 strong, to County Waterford, while Liam Deasy and Dan ‘Sandow’ O’Donovan led another contingent of about 150 men in County Limerick, where at least nine Cork men were killed on either side in July 1922.[19]

This fighting in Co. Limerick was not one sided and around 200 National Army prisoners came back to Cork from the front around Kilmallock and were housed in Victoria Barracks, in the city.

However the front would soon collapse as part of a bold plan, hatched by pro-Treaty general Emmet Dalton to outflank the fronts in Limerick and elsewhere by seaborne landings on the Cork and Kerry coast.

As the infant Free State had no navy (apart from the Helga, a coastal patrol vessel which had participated in the rising of 1916 on the British side), civilian ships were commandeered: the Lady Wicklow and Arvonia, which would transport the troops, mostly composed of the Dublin Guard, the National Army’s first unit, south.

The seaborne landing strategy was extremely risky. According to one participant on the Free State side, Niall Harrington, it ‘could have been our Gallipoli’ – referring to the very costly British and French landings on the Turkish coast seven years before, in which thousands of British and Commonwealth troops, including many Irishmen, had been killed.[20]

However the anti-Treaty IRA in Munster, as well as a total lack of heavy weapons, did not have even close to enough fighters to man all the coastline and many of their best units were fighting elsewhere. The landing at Fenit in Kerry on August 2, which embarked 450 National Army troops under Paddy O’Daly, went surprisingly well for the pro-Treaty side. No effective resistance was encountered at Fenit and the Free State force took the town of Tralee after some hard fighting that left nine pro-Treaty and two anti-Treaty combatants dead with a further 20-30 Free State wounded[21].

The landings in County Cork were to be at six days later at Passage West, Youghal and Union Hall, with the largest force, 450 strong, under Dalton himself at Passage.

Initially Dalton’s plan had been to steam straight into Cork city, again showing the almost reckless audacity that characterised the operation.

Cork harbour however had been mined by the anti-Treaty side and partially blocked by sunken barges. Cobh was briefly considered as an alternative, but being an island it would have almost certainly seen the pro-Troops pinned down and stuck at the one crossing point to the mainland. As a result, Passage West was chosen at the last minute by Dalton for the landing point.

Emmet Dalton’s original plan was to steam straight into Cork city, but was diverted to Passage West at the last minute.

In 1922, the harbour of Cork was dominated by large naval forts, at Spike Island, near Cobh, and under the Anglo-Irish Treaty, these were still occupied by the Royal Navy. The latter had partially blockaded republican-held Cork in order to stop war supplies being imported but had not been told of the Provisional Government’s plans to attack Cork by sea. They had in fact turned down a request by Collins to hand one of the forts over to the pro-Treaty government for the operation. When asked by Dalton for a pilot to guide them into Cork harbour the British naval officers responded ‘what for’? And refused to give one when not answered.

Nevertheless, the pro-Treaty forces did receive some aid from the Royal Navy commander Captain Sommerville, who, once he had figured out what was happening, cleared some of the sea mines and partially cleared the passage into Cork harbour of sunken vessels.[22]

The other two landings at Youghal and Union Hall met only minimal resistance. The main opposition the pro-Treaty forces encountered took place on the road to Cork.

The two sides

Despite some desultory firing, the Passage West landing was unsuccessfully opposed by Passage and Cobh garrison, the latter firing at some distance from across the bay. Mick Leahy the commander of Cork IRA No. 1, Brigade thought, ‘our poorest men were at Passage’ (in fact there were only eight men there with one machine gun).

Firing from the Cobh garrison was eventually silenced only by shell fire on Fota House by the National Army field gun.

Most of the fighting, though, to try to stem the advance of Free State forces towards Cork (only some 11 km away from the landing site) was carried out by men from the city and hurriedly brought back from other fronts by train.

Republican resistance to the Free State forces’ landing at Cork was hastily improvised and they were both outnumbered and outgunned.

As John Borgonovo has shown, the republicans knew that there likely to be a landing in Cork but according to one anti-Treatyite, ‘the [Free] Staters weren’t expected so soon’ and the landing caused ‘panic’.[23]

Tom Crofts, an officer of Cork No. 1 Brigade recalled: ‘our best men were at Kilmallock’… ‘they had been line fighting for weeks and had very little sleep’. Similarly Mick Murphy remembered, “I commandeered a train [from Waterford] and we brought the train back to Cork…we threw our crowd in front of the Staters but we couldn’t stem them, we had about 80 men’.[24]

In total, then, there were no more than 200 anti-Treaty Volunteers facing over twice that number of pro-Treaty troops. The anti-Treatyites had rifles and machine guns but no heavy weapons apart from ‘River Lee’ improvised armoured car, which as Anthony Barret has shown, was notoriously prone to breakdowns.

Though Divisional commander Liam Deasy was in Cork city and IRA Chief of Staff Liam Lynch was nearby at Fermoy, command of the anti-Treaty fighting line seems to have been taken first by Mick Leahy and then by Tom Crofts, with the men on the ground led by Dan ‘Sandow’ O’Donovan . Liam Lynch gave only a general order that ‘our forces are to delay and contest the advance’.[25]

Emmet Dalton, who commanded the pro-Treaty forces, had served as an officer in the British Army in the Great War, prior to joining the IRA in 1921, as had one captain Peadar Conlon, but most of his officers were IRA veterans only, mostly stalwarts of Collins’ pre-Truce Intelligence Department, including Liam Tobin and Tom Kilcoyne. Tom Ennis, Dalton’s second in command had been badly wounded the year before leading the IRA raid on the Customs House.

While some of the pro-Treaty troops were also veterans either of the British Army or of the IRA, many were raw recruits. A survey of the ten confirmed fatalities on their side shows three veterans of the British army, no confirmed IRA veterans but seven raw recruits including two teenagers, the McKenna brothers from Phibsborough in Dublin, who were both killed outside of Rochestown.[26]

Nevertheless, the pro-Treaty National Army both outnumbered and outgunned anti-Treaty IRA whom they encountered on the road to Cork both in numbers, artillery, and armoured vehicles.

Fighting at Rochestown and Douglas

The hastily assembled anti-Treaty force – initially all that could be assembled from Cork city, numbering just 36 men, attempted to block the pro-Treaty forces’ advance first just outside of Passage West and then in a stronger position near the village of Rochestown, where they occupied a series of cottages on the heights.

The road from Passage West to Cork passed through a series of small but steep and wooded hills and clearing it was by no means easy, even for the numerically and firepower superior National Army troops. There was also a railway line from Passage to Cork but it had been blown up by the anti-Treatyites upon the Free State forces’ landing.

There followed quite fierce fighting in and around Rochestown but the 18 pounder gun was was used to suppress machine gun positions, and flanking attacks by National Army parties eventually ousted the republicans from their first line of defence. At least seven National Army soldiers were killed however, on August 8 and more wounded, including one of their officers Peadar Conlon, who had the tops of his fingers blown off and later a had his face peppered with shotgun pellets.[27]

Ant-Treaty forces occupied a series of hilltop positions, first at Rochestown and then at Douglas, blocking the road to Cork city

The anti-Treaty forces retreated to another hilltop position at Douglas, where they occupied Maryborough Hall, the Golf Club, and monastery, and were joined by further reinforcements from Limerick and Waterford. There was again, on August 9, sharp, often close quarters fighting as National Army and IRA fighters encountered each other suddenly from behind sharp bends in the rural roads and across hedgerows.

At one point, Lieutenant Conlon was head to say ‘the day is lost’ as National Army troops appeared to retreat in disorder, only to forced back into the firing line by officers waving revolvers.[28]

But ultimately, again, the pro-Treaty forces’ artillery piece was brought into play and the republicans’ position was eventually flanked by National Army units under Frank O’Friel and Tom Kilcoyne and the IRA fighters were forced to retreat. Some of the last casualties were a party of the three IRA men who were cut down as they attempted to flee a rear-guard position in Cronin’s Cottage – one of whom Ian ‘Scottie’ McKenzie was a Scot, known locally for wearing a kilt and playing bagpipes, who mother had moved to Ireland to escape conscription during the Great War.[29]

There was also a fleeting clash in the lanes around Douglas between the armoured cars of the two sides as the anti-Treatyites retreated.

A local doctor, Tim Lynch, whose house stood within the combat zone, treated the wounded from both sides and described how he saw ‘sixteen [bodies] laid out’ in his house, including seven pro-Treaty soldiers killed by fire as they tried to cross ‘Morgan’s cornfield’ and two IRA men killed at Cronon’s Cottage. He described twelve further wounded lying in his study, which he described as ‘a shambles’ with blood all over the floor.[30]

In total between 10-12 National Army and five anti-Treaty IRA men (though no civilians) were killed and up to 75 wounded over two days in the fighting at Passage West, Rochestown and Douglas.

By August 10, however, the anti-Treaty leadership had made the decision not to attempt to hold Cork city but to retreat into the countryside and resume guerrilla tactics.

Retreat from Cork city

Liam Lynch had never been confident in IRA’s ability to act as conventional army. He and Liam Deasy decided not to defend Cork city, but to burn their barracks and retreat. It seems that this decision was taken as early as the first day of fighting as the IRA began to destroy stores and the phone lines in the city. The publicity department under Erskine Childers was among the first to leave Cork for Macroom.

Deasy in particular was keen to justify his decision to withdraw as having been taken to spare civilian life and the city from destruction.

They did however set fire to the military and police barracks they had been holding, shrouding the city in deep cloud of smoke. They also smashed up the printing press of the Cork Examiner and destroyed the main train lines heading into the city, blowing up the viaducts at Chetywnd and Rathpeacon and later that at Mallow too.

The anti-Treaty leadership took the decision on August 10, not to defend Cork city, their forces retreated to Macroom in some disorder.

Even here though, there were half measures. Liam Lynch cancelled plans to destroy the Customs house and also of the Bridewell or jail and of the timber yard. [31]

A ‘long convoy’ of anti-Treatyites departed at noon from Union Quay barracks in Cork towards Macroom, and the last did not leave the city until five pm. The two hundred or so National Army prisoners whom they had been holding were marched away but then set free.

The Free State forces entered Cork unopposed on the evening of August 10. There was much derision of the anti-Treatyites’ defeat and withdrawal by their enemies. Emmet Dalton wrote: ‘It is hard to credit the extent of the disorder and disorganization displayed in the retreat‘[32]. Another eyewitness saw them, ‘marching raggedly, no military precision about them… they had not been properly fed and had slept rough… they were a rabble and they knew it.’[33]

But even those on the anti-Treaty side paint a similar picture of the retreat. The writer Sean O’Faolain, then a young IRA member, saw them arrive in Macroom;

‘We could hear them coming in all night long, in trucks, private cars, by horse and cart, using anything and everything they could commandeer and when we rose the next morning, we surveyed the image of a rout. Some of these men had been fighting non-stop for a week and as they poured into the grounds of the castle they had fallen asleep where they had stopped, on the grass, in motor cars lying under trucks, anyhow and everyhow, a sad litter of exhausted men.

The extraordinary sight left us under no illusions as to our ‘army’s capacity to form another line of battle. In fact there was nothing left for most of them to do but to scatter, go into hiding, slip back at night into the city like winter foxes and lie as low there as a hunted fox’. [34]

Civilian reaction

Many civilians welcomed the Free State troops but others took the opportunity to loot in the brief window between the departure of one set of armed men and the arrival of another.

Emmet Dalton set up his headquarters in the Imperial Hotel, from where issued a proclamation on August 12 calling on citizens to set up a civil administration until the state’s functionaries could be brought in.

The business community set up a ‘civic patrol’ police which operated until the Civic Guard (later renamed Garda Siochana) arrived November 1922, the banks were reopened and unemployment benefits, which had been suspended when Cork was out of state hands, were restored.[35]

Another method of alleviating the unemployment in Cork city was found by large scale recruiting into the National Army – indeed 800 men were recruited there within a week of Dalton’s arrival.

Bishop Coholan, who had always refused to meet anti-Treaty commanders, met and congratulated Dalton on this victory.[36]

It appeared as if normality, or at least state power, as represented by the new Provisional Government, had been restored. This was, however, an illusion.

Aftermath: the Civil War that failed to end

Liam Lynch abandoned Fermoy next day and ordered the formation of guerrilla columns of no more than 35 men each.

The anti-Treaty IRA in Cork had been dispersed but not destroyed and concentrated in the hilly country of West Cork, proved much better much better at guerrilla warfare than they had at the defence of fixed positions.

Emmet Dalton blamed National Army General Eoin O’Duffy’s slow advance from Kerry for not trapping anti-Treaty forces and bringing an early end to the war. Dalton acknowledged the very partial nature of their victory at the time; ‘our forces have captured towns but have not captured irregulars and arms on a large scale.. our present dispositions are exposed to guerrilla warfare… [we are] scattered and easy to isolate’.[37]

Among the National Army’s many subsequent casualties in the county was commander in Chief, Michael Collins, who was killed in an ambush at Beal na Blath on August 22, 1922.

‘Our forces have captured towns but have not captured irregulars and arms on a large scale’: Emmet Dalton.

By September 1922, the pro-Treaty position in Cork had deteriorated badly, as had the bitterness of the conflict. On September 3, 1922, Emmet Dalton wrote to his superiors that he knew the ‘Irregulars’ ‘who caused me 17 casualties yesterday’ and urged the government to pass laws allowing executions, ‘it is better to try and execute them than shoot them out of hand when I catch them’. He said that there were about 1,000 ‘enemy’ in West Cork and that he wanted to attack them but was short on food and rifles for his troops.

On the 13th he reported that the situation in Millstreet, Macroom and Ballyvourney (West Cork) was ‘very bad’ with ‘a large concentration of irregulars’. The town of Kenmare in Kerry had been taken by them and they also held the area around Ballyvourney in West Cork. He reported that he had only 500 ‘reliable men’. And implored GHQ to ‘send rifles without fail’. [38]

It looked on August 10, 1922 as the Irish Civil War had ended, with the triumphant entry of pro-Treaty troops in to Cork. Ultimately, though, it took many more months and the deployment of thousands more National Army troops to the county before the guerrilla campaign there was subdued. The conflict ultimately cost over 250 lives in that county alone.[39]

Conclusion

The Cork landings were a risky but very successful operation by pro-Treaty forces and did indeed seize the Free State’s second city after relatively brief fighting.

The pro-Treaty side were aided by British dominance of sea including the approach to Cork and by their supply of weapons but their own determination and cohesion also played a role in their victory. This boldness and resolve masked temporarily the many deficiencies in the National Army and exposed those in the IRA, which was not at all well suited to fighting a conventional war of positions.

Furthermore the Anti-Treaty reluctance to wage war at that point meant that Cork city saved an urban battle, which without doubt saved many lives and material destruction.

However the very ease of the pro-Treaty side’s victory in Cork meant that the anti-Treaty IRA in the county were neither destroyed nor captured and they waged a determined and bloody guerrilla campaign for many months thereafter.

If you enjoy the Irish Story and wish to support our work, please considering contributing at our Patreon page here.

References

[1] John Borgonovo, The Battle For Cork City, Mercier, 20, p.85-86

[2] John Regan, The Irish Counter Revolution 1921-1936, Gill and MacMillan, 2001, p.32

[3] Dail debates, 16 December 1921

[4] Richard Mulcahy papers, UCD, 19/7/1922, P7/B/40

[5] Military Service Pension Collection (MSPC), Nominal Rolls, 1 Southern Division. http://mspcsearch.militaryarchives.ie/brief.aspx

[6] Borgonovo, Battle for Cork City, p.21

[7] Michael Hopkinson, Green Against Green, The Irish Civil War, Gill and MacMillan, 2004, p. 233.

[8] MSPC, Nominals Rolls, Cork I and III Brigades. No 1 fell from over 4,000 in July 1921 to just over 2,000 men in 1922 and No. 3 from over 2,300 to just over 1,000 men in July 1922.

[9] Election results for Cork Borough (city) here. For Cork East and North East here and for the confusingly named Cork Mid/North/South/South East and West here.

[10] Ibid. see link above.

[11] Eoin Neeson, The Civil War In Ireland, Mercier, 1966, p.148

[12] Ibid, Also Borgonovo, Battle for Cork City, p.60

[13] Borgonovo, Battle for Cork, p.5052, Also Neeson, Civil War, p.145-147

[14] Mulcahy papers P7/B/40 report from Cork by M O’Connell, 19/7/1922

[15] Borgonovo, p. 52-54

[16] Ibid.

[17] Collins memo on General Situation 27/7/22 Mulcahy Papers, UCD P/7/B29

[18] Cited in Michael Hopkinson, Green Against Green, The Irish civil War, p.162

[19] See our article on Civil War casualties in Co. Limerick here. Four of these were anti-treaty IRA. Another five Cork men died in the fighting in south Limerick on the pro-Treaty side in July 1922.

[20] Niall Harrington, Kerry Landing, August 1922, an Episode of the Irish Civil War, Anvil, 1992, p.91

[21]Harrington, Kerry Landing, p.130-131

[22] Borgonovo, Battle for Cork, p.68-69

[23] Borgonovo, p.68, Hopkinson, p.163

[24] Hopkinson, Green Against Green, p.163

[25] Ibid,

[26] See our article on Civil War casualties in Cork.

[27] Borgonovo Battle for Cork, p.90-93

[28] Borgonovo Battle for Cork, p.101

[29] Ibid.

[30] Carlton Younger, Ireland’s Civil War, Fontana, 1979, p.419

[31] Borgonovo, Battle for Cork, p.90, 110-113

[32]Hopkinson p 164

[33] Hart, IRA and its Enemies p119

[34] Sean O’Faolain memoir Vive Moi (Sinclair Stevenson, London 1993), p.154

[35] Neeson, Civil War in Ireland p.154

[36] Borgonovo, Battle for Cork, p.120-124

[37] Cited in Hopkinson, Green Against Green, p.164

[38] Irish Military Archives, CW/OPS/01//02/06, Radio reports to GHQ

[39] Or article found 220 deaths in County Cork from January 1922 until December 1924, but a study at UCC by Andy Bielenberg found at least 234 deaths from the outbreak of the Civil War until the IRA Dump arms order of May 1923. Meaning that the post-Treaty death toll there was at least 254.